3. Learning is Hard Work

Learning is Hard Work

Learning is difficult, takes work, and, frankly, is hard to do! Have you ever seen a baby learn to walk? They try and cry, and then repeat many times until they can do it. Even then, babies are wobbly and need practice. Still, they continue- no baby ever says “I’m not perfect at this, forget it, I’m not going to walk.” College learning is hard work, too. At a glance, it looks like the work you did in elementary and high school. But when you start to dig in deeper, it’s different.

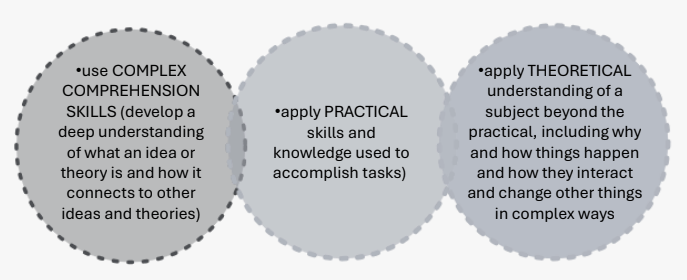

College-level learning requires that you:

Yes, in some classes, you will be expected to memorize (I’m looking at your anatomy, physiology, and math), but that is because it is the first step in learning the content within those disciplines. You need to have things memorized in order to use them, but you will need to be able to move past memorization to demonstrate that you understand, apply, analyze, and use your knowledge.

To jump from childhood educational learning to the deep and enduring learning you need in college and beyond, you’ll need to understand how your brain works, strategies that help you learn, and ways of monitoring your progress.

There is much more to college learning, so let’s dive in!

After all, you are here to learn- and you will need to continue to learn throughout your life if you want to thrive!

– Dr. L

Why is college learning hard work?

Of course, college is hard work. Even so, many students enter college without accurate expectations of what college learning is and isn’t. It is easy to underestimate how much work college is- after all, compared to high school, you spend so much less time in class and usually have more time between assignments. You also get to schedule your time and time for your work. All of this sounds great- until it isn’t great. College asks you to think more deeply, be responsible for your time and learning experiences, and ask for assistance when needed. The college environment expects that you already have (or can quickly build) skills like time management, work management, organization, reading, note-taking, studying, and self-efficacy without having someone telling you what you need to do and how to build these skills.

It’s easy in college to misunderstand what learning is (and isn’t) and to ignore or avoid what is expected of you.

How much time do you plan to spend on college work?

Any one course is typically manageable. The work can be challenging and difficult, but if it is the only thing you need to do, you could likely do it. College students usually take more than one course, though.

The complexity increases as you add more full-time college students who take at least 12 credits. Courses are not aware of each other’s timelines and workload. The freedom to complete work when it is best for you can encourage dangerous habits like procrastination- ending with you turning in no work, late work, or work that is not your best (no matter how it scores against instructor expectations). Spending less time in class means needing more time to work on your learning on your own.

For every 1 credit hour of class, you should expect 1-3 hours of independent learning (like studying, homework, reading, and writing).

So for a 3 credit hour class, expect and schedule 3 to 9 hours of work!

Let’s multiply that by 12 credits- you need to schedule between 12 and 36 hours of learning on your own!

| 12 credits * 1 to 3 hours of independent learning | = | 12 hours in class PLUS 12 to 36 hours per week for a total of 24 to 48 hours! |

Most full-time students take 15 credits.

| 15 credits * 1 to 3 hours of independent learning |

= | 15 hours in class PLUS 15 to 45 hours per week for a total of 30 to 60 hours! |

Does it sound overwhelming? It certainly can be! Many first-year students need help managing their workload, scheduling their time, and making sure they manage priorities first. For students who need to or choose to work, these hours can be overwhelming and set them up for failure, even if things are manageable at the beginning of the semester.

You should expect to do MORE work in online classes than in traditional classes, especially in asynchronous classes (meaning they do not meet live).

Understanding the expectations of college learning is very important—to be successful, you have to know what your instructors want from you and how you should manage yourself and your workload.

What kind of learner were you in high school?

Who were you in high school when it came to learning? Maybe you were a strong student who handed things in on time. Maybe you were a creative student who took new approaches to the work assignment. Maybe you were a scattered student, pulled in many directions- for example, sports, school organizations, a part-time job, and social life. The student you were in high school may still be who you are in college. It is important to know what you struggled with AND how you want to manage those challenges in college.

- Ask yourself

- What type of assignments did I do well on, and which were difficult for me?

- How do I feel about myself as a student?

- What things got in the way of my assignments and studying?

- Where did I complete my work?

- How did others view me as a student? (including teachers and other students)

- What did studying and assignments prevent me from doing that I wanted to?

- Did I do my assignments on time?

- When did I complete my work?

4 big areas you might want to consider about yourself and how you FEEL towards yourself as a learner and your PERFORMANCE as a student

![]() Reading: how you process written words to understand their structure, language, and purpose, identify ideas, and infer meaning in an independent and sustained way.

Reading: how you process written words to understand their structure, language, and purpose, identify ideas, and infer meaning in an independent and sustained way.

![]() Math: your ability to use numbers, calculations, mathematical functions, geometry, variables, equations, and complete word problems

Math: your ability to use numbers, calculations, mathematical functions, geometry, variables, equations, and complete word problems

![]() Writing: your skill in writing in a coherent, clear way, focused on content and goals, with good grammar, paragraphs, and overall organization

Writing: your skill in writing in a coherent, clear way, focused on content and goals, with good grammar, paragraphs, and overall organization

![]() Self-regulation: managing yourself as a learner refers to managing your emotions and learning, including planning, monitoring, anxiety management, and a mindset focused on mastery (not just grades). Self-regulation also means managing your time and work and knowing how and when to ask for help.

Self-regulation: managing yourself as a learner refers to managing your emotions and learning, including planning, monitoring, anxiety management, and a mindset focused on mastery (not just grades). Self-regulation also means managing your time and work and knowing how and when to ask for help.

These four skill sets provide the foundation for your learning.

While you may be stronger in one and weaker in another, you’ll want to build strong skills in each of these areas to manage the challenges of college learning—both the content and the learning process itself.

What is college learning, and how is it different from high school learning?

High school learning is filled with rules. You are typically told what to learn, how to learn it, and how to demonstrate your understanding or mastery. You likely had detailed assignments and rubrics or other information about how your work was scored. Your teachers were trained to be teachers- while they knew about a subject or content area, they spent time in college learning about how people from 3 years old to 18 years old typically learn and develop. Your learning was structured, with times and teachers who collaborated and communicated with each other. High school learning was focused on YOU and helping you learn.

Let’s compare high school and college:

|

High school

|

College

|

And then you get to college… and trade rules for responsibilities

College learning is filled with responsibilities. You are not told what to learn, how to learn it, and how to demonstrate your understanding or mastery. You are often given assignments and expected to find out how to complete them on your own. Your faculty instructors are experts in their fields but typically have little to no background in how adults learn. They may care very much about your learning, but that does not translate to them being “teachers.” Faculty are called professors for a reason- because their expertise lets them know and explain topics- but not monitor your learning. College instructors usually do not have contact with each other, are unaware of workloads and expectations for other classes, and seldom collaborate, even within their own departments. Many college instructors are adjuncts (part-time on short-term contracts), meaning they only teach 1 or 2 classes, do not have an office on campus, and are only present for the classes they teach- and are not able to get involved in many campus activities.

Rules told you:

- What to do

- When to do it

- How to do it

- Expectations

- How it would be graded /rubrics

Responsibility expects you to know and manage:

- What needs to be done

- When it needs to be handed in

- How to ask for and receive help

- The level of quality and depth of your work

Demonstrating learning: Bloom’s taxonomy reimagined

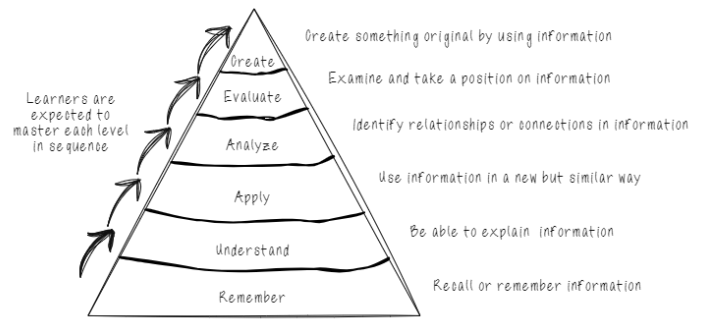

A taxonomy is a way of organizing something, in this case- levels of learning. In Bloom’s Taxonomy, learning progresses from the basic level of knowing to the highest level of creating. Bloom plots learning as a sequence where you demonstrate your knowledge at each level through specific activities before moving on to the next level.

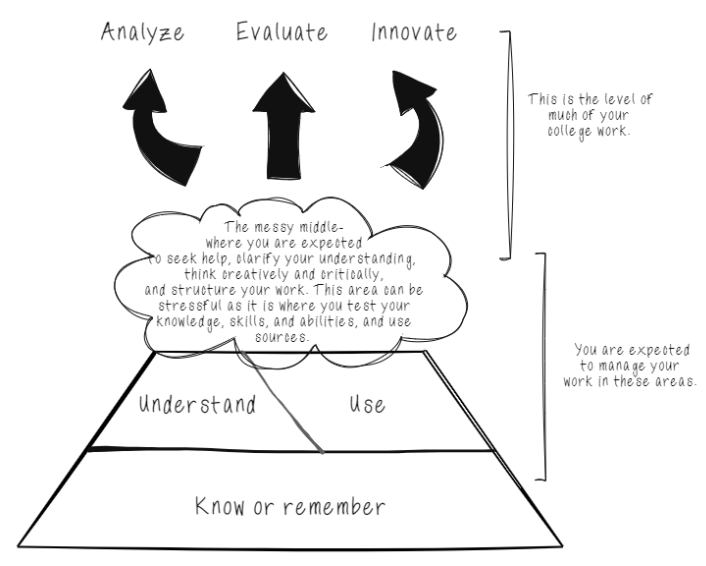

If we reimagine this taxonomy for college, it becomes less step-by-step and looks more like this, where the foundation is knowing followed by and understanding and using knowledge as explained (by faculty, readings, or other resources) and then a space where you increase your knowledge and skills, followed by three more ways of using what you know- any of which you could be asked to use in a college class.

Taxonomy of College Learning

Understanding each level of learning can help you decide how to approach and assignment and what your instructor is looking for from you. Each level has specific words that to look for.

The first areas form the basis of learning that you are likely familiar with from previous learning experiences.

| Level | About this level | Words to look for |

|

| Know | Knowing, or remembering, is the first level of knowledge. It allows you to build your vocabulary and theory knowledge. Assignments for this level involve showing you know about something or can identify the language or parts of the topic. |

|

|

| Understand | Understanding involves your ability to internalize and explain a topic. Assignments at this level ask you to demonstrate your understanding of the topic. |

|

|

| Use | Applying, or using your knowledge relates to your ability to use what you know in situations or problems that are similar to how you learned them (so you can apply the work as you were taught. Assignments at this level ask you to replicate what you’ve done, with similar but new problems, situations, or content areas. |

|

|

The next 3 areas (analyze, evaluate, innovate) refer to ways you can demonstrate your mastery of topics beyond using the material in classes. For example, you might:

| Level | About this level | Words to look for | |

| Analyze | Analysis asks you to look closely at work (for example, writings or data), think about the content and how it was formatted, and explain your understanding using theories and other knowledge gained in a class. Assignments might ask you to identify connections, interpret relationships, or locate key parts in structure and content. |

|

|

| Evaluate | Evaluating refers to looking at a source, topic, or other item’s merits (or good or bad points). Evaluation assignments may require determining how and why something was created by considering the author, how it was rated, and the topic’s accuracy and value. In evaluation, you determine if the work does what it is supposed to and if it should be accepted based on its good and bad points, how it was created, and who created it. You’ll also determine its limitations (where it can be used and what it should not be used for) . |

|

|

| Innovate | Innovating or creating is a level where you use your learning to create new and novel works. Assignments you might find at this level include creating new solutions to problems, creative works that showcase new methods and ideas, and designing and building unique examples of work |

|

|

The mismatch between expectations as a student and the requirements of a course can cause frustration, confusion, and low grades. I’ve seen many students get upset because they think they are doing what is expected when working at the level of “know” when they need to be at “analyzing.”

Understanding the depth of a class

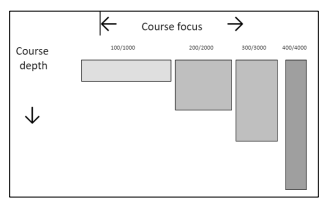

College classes are often numbered, starting with 1, 2, 3, or 4. These numbers often correspond to the year you could take them- for example, a 100 or 1000 course in the first year and a 400 or 4000 course in senior year. With that in mind, you’d think that the content is harder. Actually, it might not be for many colleges- as course numbers reflect the depth and breadth of the course, not the difficulty level. Let’s look at this in more detail.

- A 100/1000 level course is often very wide (breadth, the variety of content it contains) and quite shallow in how much it covers each topic (depth, the level of detail it goes into on the topics in the course). So, a 100/1000 course might cover many topics at a very introductory level, introducing key theories, ideas, people, concepts, and skills. At the end of an introductory course, you will have a foundation of general knowledge to move more deeply into the ideas covered- but you likely will only know a little about any topics.

For example, a 100/1000 level psychology course will teach you the basics about key theories in psychology, vocabulary, skills, and ideas you need to understand what psychology is, as well as the key people in history. With so much to cover, you’ll learn just enough to get started and move on, but not much about any topic in depth. In fact, if you look at a syllabus from a course like this, you will likely see topics changing each week!

- Other introductory or survey-style courses could be found in Sociology, English, Science, Anatomy and Physiology, Music, or Art—all providing an overview of the subject at the college level. It can be tempting to think you can skip these courses, especially if you’ve learned a bit about the topic in high school, but the material covered in college will be deeper than in high school and will help you see the topic in a new way.

- A 200/2000-level course has less breadth and is likely to cover fewer topics. Instead, 200/2000 courses cover a smaller list of topics in more detail for each one. Instead of switching between topics each week, you’ll find that your topics are more likely to build on each other to create more depth in your understanding.

Things to know about college

College learning is different from learning in other areas, including high school or career/workforce learning. Although there may be similarities in some areas, do not underestimate the workload, depth, and expectations of college.

College learning

|

Is independent You’ll spend most of your learning time on your own, outside the classroom. You will manage your own work, assess your learning and knowledge, and complete work. You are responsible for digging deeply into topics, seeking new information, and using support and assistance as needed. |

Increases work difficulty Work may seem like what you’ve done before but will require more effort and thought. The depth of a college class is much deeper than what you have in high school- and requires you to focus on complex topics and ideas. A note: if it seems easy, you likely need to review the material, as you may have missed something. |

Has a heavy and fast-paced workload Material is covered quickly both in class and in homework. You may be asked to do extensive work quickly. Papers, tests, and projects may have very short time frames. Classes do not consider other responsibilities you have, which can lead to very busy weeks and months. |

|

Requires extensive reading College classes expect heavy reading from students. In fact, some classes can ask for 100 pages in a week! Effective reading requires strategies- careful steps that ensure that you understand what you read, take effective notes, and can use readings. Most classes assign readings before lecture or activities, with the expectation that you will know the ideas and vocabulary for use in class.. |

Uses critical and creative thinking In college classes, you are expected to take in the explicit (what is said) meaning of information and then look at it from many viewpoints and perspectives. You are also expected to take information and see how it applies to what you know and to other contexts. Creative (unique ideas ) and critical (objective analysis ) thinking help you generate new ideas and work. |

Has new expectations Sometimes college seems like high school- even though it isn’t. You may be asked to use things you learned in high school, but you’ll likely be expected to do more, think more deeply, read more widely, and work harder. If you continue to expect that what worked in high school will work in college, you will likely find that you do not do the quality of work that is expected – or reach what you are capable of. |

In many ways, college may seem familiar to you since you’ve been learning it throughout your life. College itself may feel like high school as it uses many of the same foundational elements. Even so, college learning is different and knowing these differences can help you to assess your learning and progress towards your goals.

Memory and learning

Memory and creating memories are critical processes for life and learning. Memory supports learning by storing information and retrieving it when needed. However, memory itself is not learning—just as memorizing (knowing) something does not mean that you understand or can use it.

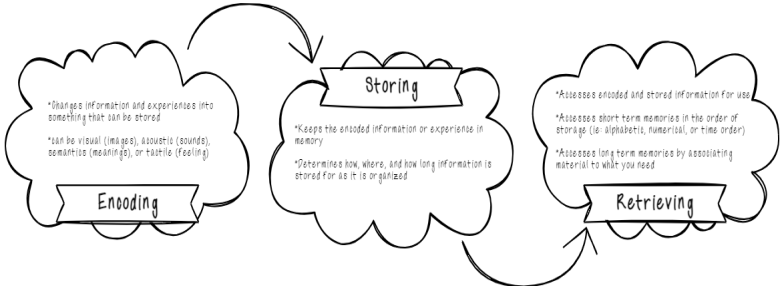

There are 3 main processes in memory:

You need all 3 of these to work well to support you as you learn new skills and knowledge. You can have weakness or strength in one (or more) of these areas (and knowing this can help you use your strengths and build up your weaker areas).

Encoding– your ability to take in information through reading, experience, and listening- is affected by many things. Imagine if you encoded every experience, everything you read or experienced. Your brain does not do this- in fact, it is highly selective in what gets encoded and what does not.

Things that encourage encoding are:

- The length of the material- it is harder to encode long material

- How organized and clear the material is- it is easier to encode organized and clear material

- How familiar you are with the material- it is easier to encode things that are connected to what you know

- The situation you are in when you heard, experienced, or read the material

- Your physical, mental, and emotional state when you heard, experienced, or read the material

- Motivation- why it is important to you and how you’ll use it

Once information is encoded, it is stored (retained) so that you can use it. During this process, your memory decides if the encoded information needs to be held in short-term (temporary) memory or long-term memory. Your memories are organized so your brain can retrieve them, with short-term memory items disappearing shortly after use and long-term memories staying in storage for when you need them.

When you need a memory, your brain then retrieves what you need. When you are cued to a memory by seeing, hearing, smelling, or feeling something, your mind is able to recognize the stimulus and then retrieve your memory. This recall is usually fast- especially if it’s for recognition (identifying something familiar to you). For full recall, your brain works fast but needs two steps: searching and retrieving items that match and then choosing which one fits what you need.

This process is not perfect, as you likely know from experience. We forget so much of what we hear, see, experience, or read- and some is stored so deeply that it takes a great deal of time to retrieve it (have you ever experienced remembering something after sleeping? That’s the retrieval process taking time as your mind locates and sorts through deeply stored memories).

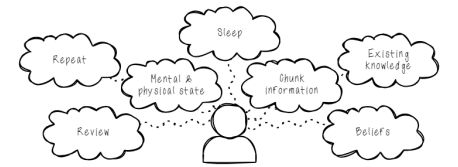

How to support your memory:

- Repeat what you want to remember.

- Do this at different times, in different places

- Take breaks between repetitions

- Quiz yourself

- Use an active process that requires you to think about the material or use it

- Review and revisit materials you need frequently over time. Memory degrades (is harder to access) the longer it sits unused. This can be as simple as thinking about what you know.

- Give yourself frequent, small tests (what we test ourselves on, we are more likely to be a retrieve and use)

- Space out your reviews over time

- Practice your skills together, not one at a time, by creating a challenging activity

- Pay attention to your mental and physical state when you learn and try to match that physical or emotional state when you want to recall that information.

- Consider your existing knowledge and beliefs related to the material (the schema or mental framework for the ideas) for your materials and consider the way that what you are learning confirms or contradicts what you already know or believe and push yourself to be more flexible in your thinking.

- Chunk your information together into blocks that are related in a way that makes sense to you.

- Make sure you sleep when your body and brain demand it- during sleep, your brain organizes information and material, which in turn supports retrieval and recall.

You probably noticed that supporting your memory sounds a lot like study strategies- and that is because “knowing” or being able to recall and retrieve information is the foundation for learning.

College learning requires self-regulation

What is self-regulated learning?

As an adult, you have the ability to regulate your own learning (self-regulated learning, or SRL). This means you can intentionally decide how you want to engage (or not engage) in your learning process.

Healthy self-regulated learning includes your ability to:

- Transform goals and work to be done into manageable tasks

- Use skills to complete tasks

- Decide what learning efforts and methods you should use

- Make decisions on what to do or not do regarding learning based on the outcome

Healthy self-regulated learning means that you intentionally decide and adapt your learning activities to your goals. As part of this process, you:

- plan and determine what you need to do to meet your goal

- perform and apply learning methods you believe will be successful

- monitor how you are doing and make adjustments when needed to your learning process, conditions, motivation,

or access support

Adding in a final step- reflection- creates a process where you manage your learning and continue to learn about yourself and what works for you.

SRL can be used in an unhealthy way, too

Since self-regulated learning is about you deciding how you want to engage or not engage in learning, you could find yourself using these strategies and making decisions that won’t lead to your success.

For example, you might choose to procrastinate instead of working, could significantly underestimate the time or difficulty of an assignment (for example, a paper, reading, or exam), or take on too much work (overcommitting), which allows you to blame your performance on the amount of work you had to do, setting up self-fulfilling prophies by deciding you won’t do well before you even start, and making excuses before you begin.

These types of academic self-handicapping strategies can be used to protect your emotions and ego from discomfort. By setting up reasons why you could fail, you are more likely to fail while deciding on how you’d explain that failure to yourself and others. This momentary protection comes at a high cost, limiting your ability to live the life you want.

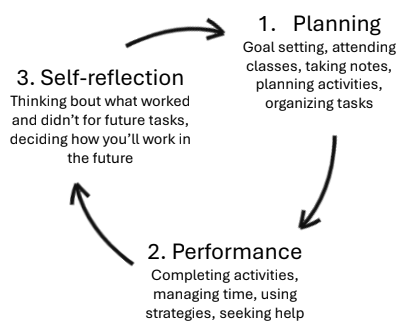

The SRL Cycle

|

1. Planning

|

2. Performance

|

3. Self-reflection

|

This process supports you in metacognition (knowing how you think and learn), motivation (your ability to initiate and maintain tasks), and behaviors (actions and reactions) that lead to learning.

Remember that the SRL is not a specific skill or task—instead, it is a cycle of behaviors you use to understand and direct your work. It focuses on YOU understanding yourself and the work you have to do in the specific class environment. As a cycle, it is continuous, helping you understand your work, performance, how you learn, and what you need to do your best.

Reflection questions

How will I schedule my time to include:

- Time in class

- Time for homework or reading outside of class

- Personal responsibilities

- Social time

- Work

What level of work have I done for classes in the past? What level do I expect in my classes this semester? (Hint: look at Bloom’s taxonomy and then look at assignments and course syllabus)

How do I regulate my own learning? What strengths can I use? What challenges do I have? What steps do I want to take next?