4 The Artistic Elements in the Design of a Park

A scene in nature is made up of various parts; each part has its individual character and its possible ideal. It is unlikely that accident should bring together the best possible ideals of each separate part, merely considering them as isolated facts, and it is still more unlikely that accident should group a number of these possible ideals in such a way that not only one or two but that all should be harmoniously related one to the other. It is evident, however, that an attempt to accomplish this artificially is not impossible, and that a proper study of the circumstances relating to the perfect development of each particular detail will at least enable the designer to reckon surely on a certain success of a high character in that detail, and a comprehensive breaking together of the results of his study in regard to the harmonious relations of one, two or more details may enable him to discover the law of harmonious relation between multitudinous details; and if he can discover it, there is nothing to prevent him from putting it into practice. The result would be a work of art, and the combination of the art thus defined, with the art of architecture in the production of landscape compositions, is what we denominate landscape architecture.

The term landscape architecture first appeared in English in 1828, in On the Landscape Architecture of the Great Painters of Italy by Gilbert Meason. In Meason’s book, the term referred “specifically to architecture set in the context of Italian landscape painting.” By the 1860s, when Olmsted and Vaux were designated the “landscape architects” of Central Park, the term meant something quite different. The landscape was not simply the context for the work of the architect; rather, the landscape itself was the work of the architect.[1]

The passage quoted above lays out the theoretical grounds for the work of the landscape architect. On the one hand, we have nature and its accidents, which on their own rarely conform to the so-called ideal. On the other hand, we have art, which can create harmony in nature, thus presumably achieving something closer to what is ideal. This framework, through which the landscape can be a composition—something made in the way that a painting or sculpture is made—makes some sense of what is to me an odd passage that appears a few paragraphs later in the 1866 report:

Although we cannot have wild mountain gorges, for instance, on the park, we may have rugged ravines shaded with trees, and made picturesque with shrubs, the forms and arrangement of which remind us of mountain scenery. We may perhaps even secure some slight approach to the mystery, variety and luxuriance of tropical scenery, by an assemblage of certain forms of vegetation, gay with flowers, and intricate and mazy with vines and creepers, ferns, rushes and broad-leaved plants. But all we can do in these directions must be confessedly imperfect, and suggestive rather than satisfying to the imagination. It must, therefore, be made incidental and strictly subordinate to our first purpose.

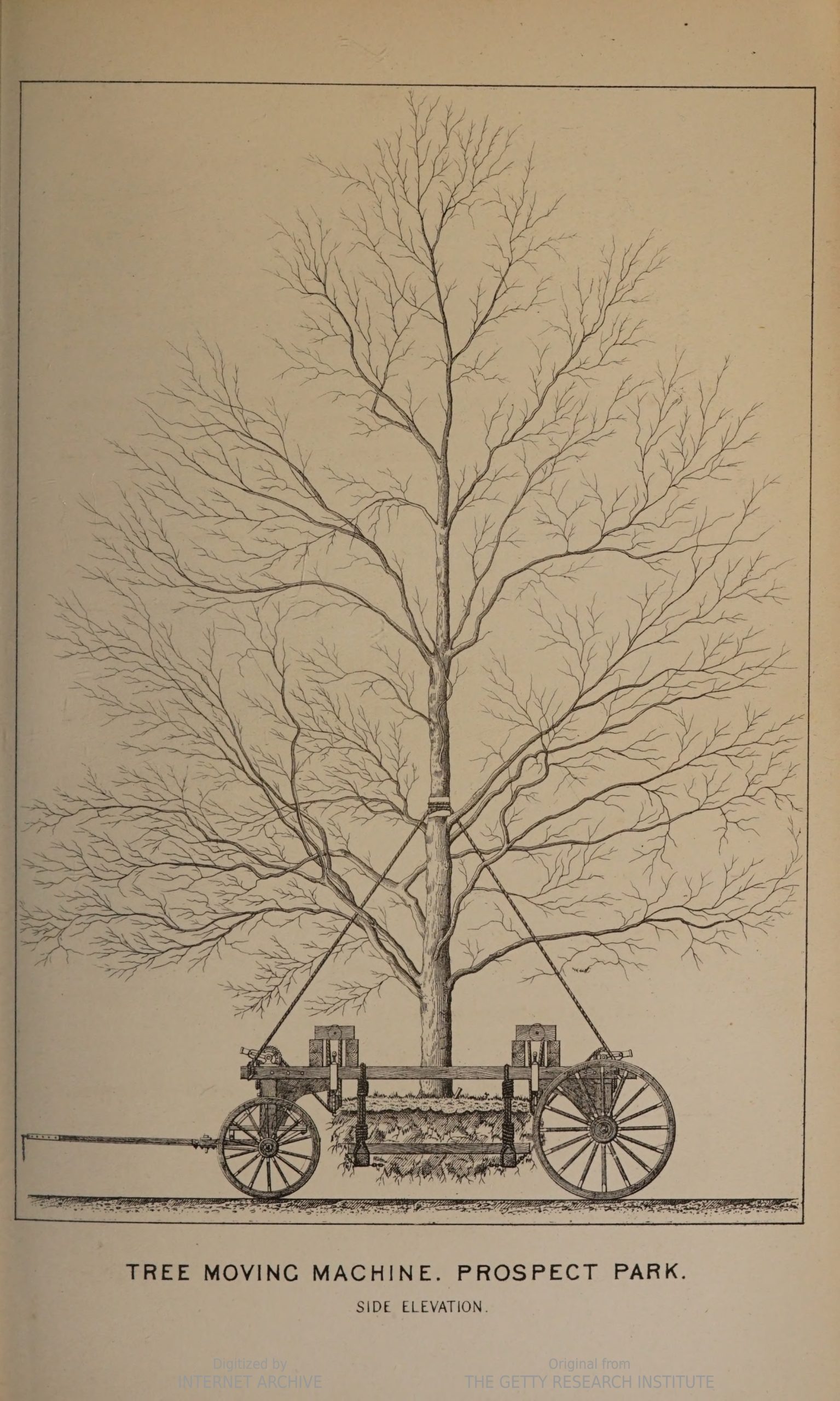

Having formed these general plans, we find, in further studying the site, its most important circumstance to be the fact, that a large body of trees already exist upon it, not too old to be improved, yet already old enough to be of considerable importance in a landscape.

The “first purpose” mentioned in this quotation is the creation of a pastoral landscape. What to me is odd is the desire also to have mountain scenery and tropical scenery on this site that Olmsted and Vaux described as having a pastoral character, which, citing Psalm 23, they say has associations that “are in the highest degree tranquilizing and grateful.” Why, then, are suggestions of mountain scenery and tropical scenery also wanted? Why seek to achieve an ideal that has so little to do with the actual? The “accident” of nature in this case seems to be the accident of actually being suitable to a particular locale.

Notice, too, that the “large body of trees” already growing on the site are described here as important—and yet subject to improvement. The trees, it seems, are the raw materials for creating something else.

- See Waldheim, C. (2014). Introduction: Landscape as architecture. Studies in the history of gardens & designed landscapes, 34(3), 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/14601176.2014.893140 ↵