2 The Universal Pleasure of Parks

Is there any pleasure which all persons find at all times in every park, and if so, what does that pleasure depend upon?

The answer unquestionably must be — That there is such a pleasure, common, constant and universal to all parks, and that it results from the feeling of relief experienced by those entering them, on escaping from the cramped, confined and controlling circumstances of the streets of the town; in other words, a sense of enlarged freedom is to all, at all times, the most certain and the most valuable gratification afforded by a park. The scenery which favors this gratification is, therefore, more desirable to be secured than any other, and the various topographical conditions and circumstances of a site thus, in reality, becomes important very much in the proportion by which they give the means of increasing the general impression of undefined limit.

In the opening pages of their 1866 report to the commissioners of Prospect Park, Olmsted and Vaux argue that “there are two possible misfortunes” of a site selected for a park, “which in no period of time, and by no expenditure of labor, can ever be remedied. These are, inadequate dimensions, and an inconvenient shape.” The site that their report proposes excludes some of the land that had already been secured for Prospect Park while it includes other land that had not yet been purchased. So the purpose of the opening pages of the report is to establish the reasons for such a drastic—and potentially costly—change in plan.

Among the reasons that Olmsted and Vaux put forth is (they claim) a universal truth: that parks give relief, and this relief comes from the “sense of enlarged freedom” felt in a park, especially insofar as its scenery gives “the general impression of undefined limit.” Their plan, they suggest, is to create a park that—despite its setting in what even then they saw was a burgeoning metropolis—gives this sense of undefined limit.

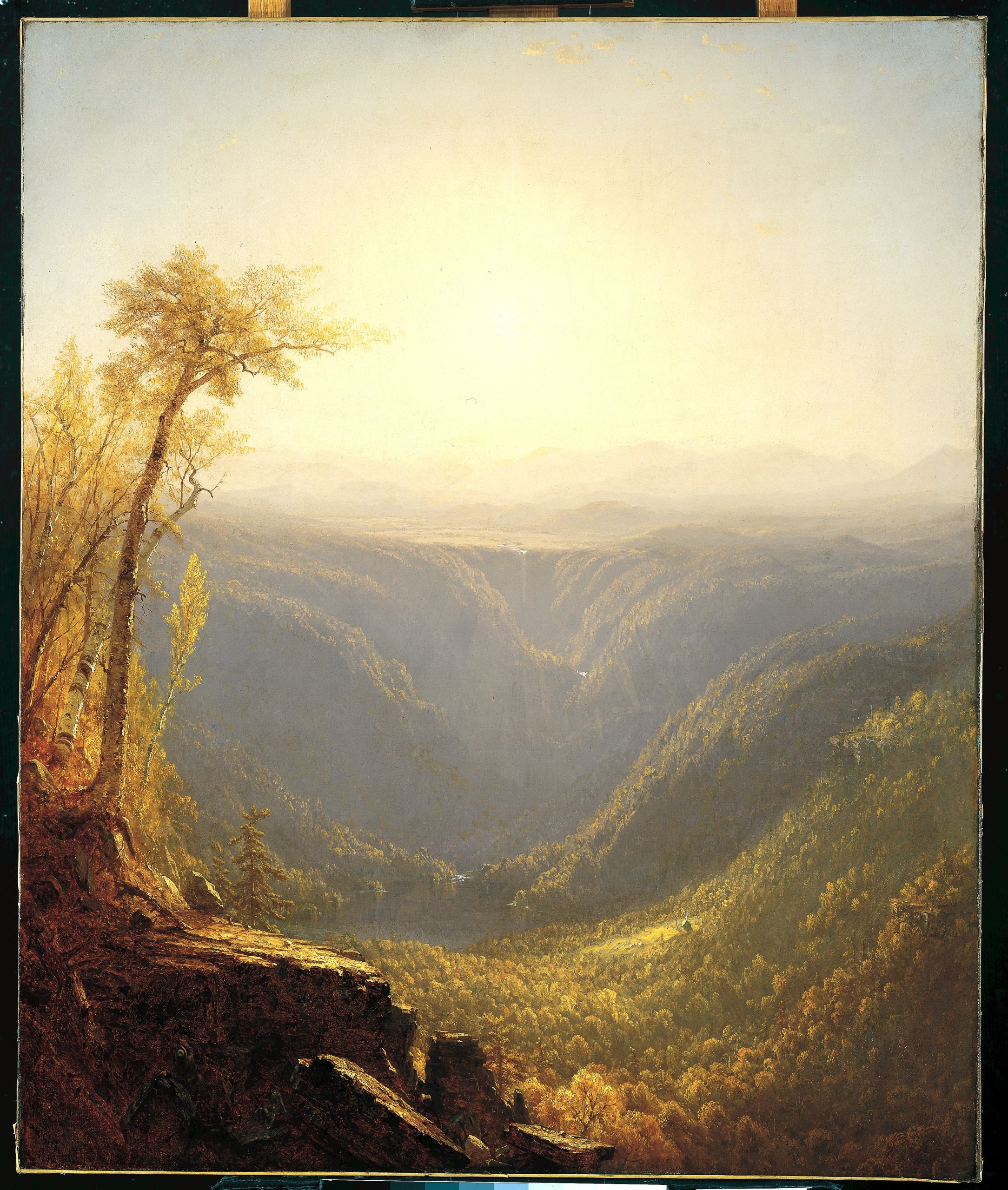

Situating the perception of freedom in a seemingly limitless landscape brings to mind the rapacious desire of certain Americans for the frontier. Aesthetically, and not unrelated to notions of Manifest Destiny, it brings to mind the paintings of the Hudson River School artists, who portrayed the American wilderness as grand and sublime, as in this 1862 painting by Sanford Robinson Gifford, in which the earth and heavens seem to be merged in a haze of sunlight.