Olmsted and Vaux’s Vision

On the 18th day of April, 1859, at the solicitation of the citizens of Brooklyn, the Legislature of the State of New-York passed the following act, entitled “AN ACT To authorize the selection and location of certain grounds for Public Parks, and also for a Parade Ground for the city of Brooklyn.”

— from the First Annual Report of the Commissioners of Prospect Park, Brooklyn

The idea that Brooklyn should have a park as grand as Manhattan’s Central Park took hold in the mid-1800s, and in April 1859 the state authorized a commission to identify sites to be reserved for public parks. Chief among the sites recommended by the commission was “That piece of land situated on what is commonly called Prospect Hill,” which, “on account of its commanding views of Brooklyn, New York, Jamaica Bay, and the Ocean beyond, of the eastern part of Kings county, of the Bay of New York, Staten Island, the Narrows, and the New Jersey shore, the undulating surface of the ground, the fine growth of timber covering a large portion of it, the absence of any considerable improvements to be paid for, has, for many years, been contemplated by our citizens as a favorite place for a park.”

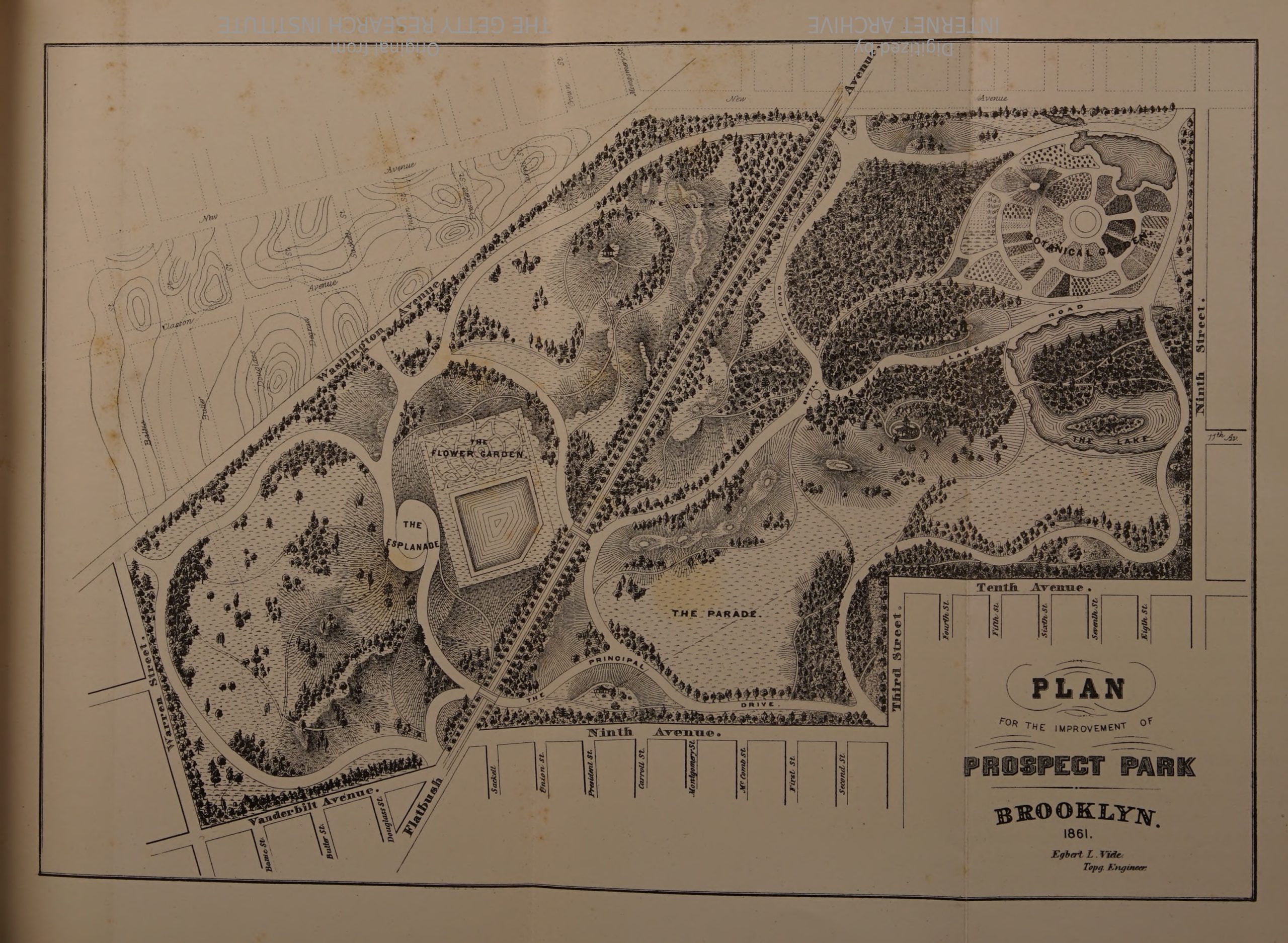

In 1861, the engineer Egbert Viele provided a design for the proposed park.

The outbreak of the Civil War intervened, however, and a few years later James Stranahan, president of the Board of Commissioners of Prospect Park, invited others to propose alternative designs. In 1865, the commissioners chose a plan proposed by landscape architect Calvert Vaux, who with Frederick Law Olmsted had also designed Central Park (for which an original plan by Viele had also been put aside). Vaux persuaded Olmsted to return from California to New York to collaborate on the job—which would result in the park some view as their masterpiece.

The main fault of Viele’s design was that Flatbush Avenue cut through its center. Additionally, a larger park was wanted. In Olmsted and Vaux’s plan, Flatbush Avenue formed a northeastern border, excluding Prospect Hill, and more of what was then farmland to the south was incorporated within the park’s perimeter. The plan encompassed “three grand elements of pastoral landscape”: a meadow, woods, and a lake.

The following pages present a discussion of excerpts from Preliminary Report to the Commissioners for Laying Out a Park in Brooklyn, New York, submitted in 1866 by Olmsted, Vaux & Co. In this document, Olmsted and Vaux describe their vision for the park, which is founded on their understanding of the purposes of parks and how those purposes are to be met.