Restoration

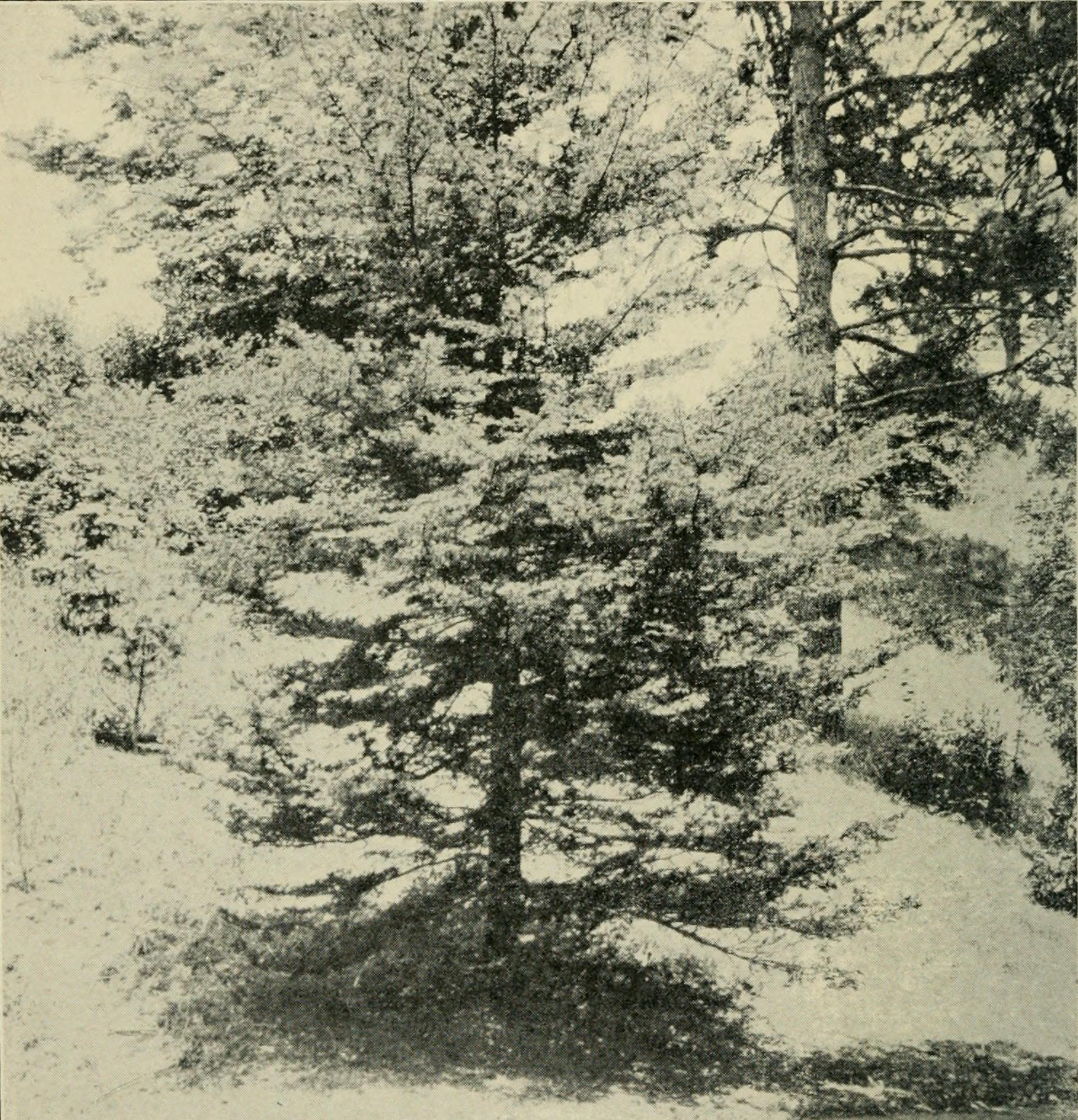

Brooklyn’s last forest, where white oak, red maple and tulip trees once inspired the poet Marianne Moore, is today a patchy grove of quick-growing weed trees.

Scientists say the forest, which covers half the 525-acre Prospect Park, is dying, a victim of mountain bikes and millions of footsteps. Not to mention a few ecological missteps by the park’s designers, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.

But now, after a Federal report warned that the woodlands face extinction, supporters have come up with a multimillion-dollar, 25-year plan to restore the arboreal soul of Brooklyn.

— from “Urban Backyard to be Revitalized” by Douglas Martin for The New York Times in 1995

In 1980, when Mayor Edward Koch appointed Tupper Thomas to be Prospect Park’s first administrator, the park was in bad shape. Years of underinvestment and neglect had left the buildings, bridges, and paths in the park to decay. Park usage was at an all-time low.

To attract visitors back to the park—and thus encourage additional support for further investment in the park—Thomas first focused efforts on repairing its landmarked buildings and bridges. The resulting increase in attendance, write the authors of the 1994’s A Landscape Management Plan for the Natural Areas of Prospect Park, was not without its price: “The landscape, neglected for over 50 years, now suffers a second assault from the sheer volume of people walking over almost every square inch of soil within the Park’s boundaries.” The Landscape Management Plan presented the plan for restoring this landscape.

The following pages present a discussion of excerpts from the Landscape Management Plan, which marked the beginning of taking a more holistic view in planning for the park. This view saw the park’s forest not only as the core of an interdependent landscape, but also as an entity with needs of its own that merited attention and care.