3 Theoretical Framework

Understanding Positionality in Knowledge Production

The Myth of Neutral Knowledge

For generations, students have been taught that knowledge is objective—that facts exist independently of the knower, waiting to be discovered through proper scientific methods. This notion of neutrality in knowledge production has dominated Western academic traditions, suggesting that a researcher’s identity, social position, and lived experiences should be irrelevant to their findings. When I introduce this concept in my classrooms, I often ask students to reflect on what “objectivity” means to them before we begin to complicate this seemingly straightforward term.

What many students discover is that the pursuit of universal, objective knowledge has often served to mask the power dynamics inherent in knowledge creation. As Hussein Bulhan (2015) argues, what we have historically accepted as “objective” has frequently been knowledge that reflects and reinforces the perspectives of those with societal privilege. The tools we use to produce knowledge—our methodologies, our terminologies, our frameworks—are not neutral instruments but are themselves shaped by historical and social contexts.

When we consider artificial intelligence, this understanding becomes even more crucial. AI systems, far from being neutral computational processes, are built upon datasets, algorithms, and design decisions made by humans with particular perspectives, priorities, and limitations. Each decision about what data to include, what questions to ask, and what outcomes to optimize for carries the imprint of human positionality. In our class, we watched a documentary called Coded Bias. Though it was made in 2020, it still raises issues that are relevant today and we enjoyed the conversation that it generated about the history of AI.

Situating Positionality: A Genealogy

The concept of positionality emerged from feminist, postcolonial, and critical race scholarship that challenged the myth of the detached, neutral observer. Donna Haraway’s (1988) groundbreaking work on “situated knowledges” argued that all knowledge claims come from particular positions—social, cultural, historical, and embodied perspectives that shape what we can see and how we interpret what we see. This doesn’t mean knowledge is merely subjective or relative; rather, it suggests that acknowledging our position allows for more honest, rigorous, and accountable knowledge production.

Patricia Hill Collins (2000) further developed these insights through Black feminist epistemology, demonstrating how knowledge emerges from lived experience and is validated through dialogue within communities. She showed how the perspectives of Black women—positioned at the intersection of multiple oppressions—offered unique and vital insights that more privileged perspectives often missed or misunderstood.

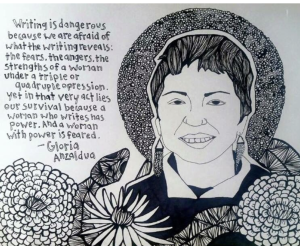

Gloria Anzaldúa’s (1987) concept of borderlands consciousness illuminated how those who live at the intersections of cultures and identities develop particular forms of knowledge precisely because they must navigate multiple ways of being and knowing. As she writes, “I am a wind-swayed bridge, a crossroads inhabited by whirlwinds… spanning abysses” (p. 85). This position at the crossroads, while often painful, offers intellectual and spiritual resources for challenging dominant knowledge systems.

From Theory to Practice: Why Positionality Matters in the Classroom

Understanding positionality is not merely a theoretical exercise—it has profound implications for how we teach, learn, and engage with knowledge, especially in an era of artificial intelligence tools. When students recognize that all knowledge is positioned, several important shifts occur:

- Critical Engagement: Students move from passive consumption of “facts” to active questioning of how knowledge is produced, by whom, and for what purposes. They learn to ask: Whose perspectives are centered here? Whose are marginalized or erased?

- Epistemic Justice: Following Miranda Fricker’s (2007) work, students develop awareness of how certain knowers are systematically disadvantaged in knowledge-sharing practices. They begin to recognize when testimonial injustice (when someone’s word is given less credibility due to prejudice) and hermeneutical injustice (when someone lacks the conceptual resources to make sense of their own experiences) occur.

- Valuing Diverse Perspectives: When students understand that their own positionality offers unique insights rather than “bias” to be eliminated, they begin to recognize the value of bringing multiple perspectives into dialogue.

- Self-Reflective Practice: Students develop habits of reflexivity—what Finlay (2002) describes as “explicit self-aware meta-analysis” (p. 209)—interrogating how their own social positions influence what they notice, what questions they ask, and how they interpret information.

Students in my classrooms often feel that objectivity means setting aside who they are. Through thoughtful pedagogy we can get to a place where our students celebrate that who they are shapes what they see in the world and that is not a weakness but rather a starting point for deeper understanding.

Positionality and AI: Navigating New Terrain

As AI tools become increasingly integrated into educational spaces, this understanding of positionality becomes not less relevant but more urgent. Students who understand knowledge as positioned can approach AI-generated content with appropriate critical awareness, recognizing that these systems, despite their computational nature, reflect human positions, priorities, and blind spots.

When using AI tools like large language models, students who understand positionality can:

- Recognize the Non-Neutrality of Training Data: They understand that AI systems trained on human-generated text will reflect the positions and biases embedded in that text, often amplifying dominant perspectives.

- Question Generated Content: Rather than accepting AI outputs as authoritative, students can interrogate the assumptions, perspectives, and limitations in AI-generated content.

- Supplement with Diverse Perspectives: Students can intentionally seek out perspectives that may be underrepresented in AI training data, particularly voices from marginalized communities.

- Value Their Unique Contributions: Perhaps most importantly, students who understand positionality recognize that their own situated knowledge—emerging from their cultural backgrounds, lived experiences, and embodied realities—offers insights that even the most sophisticated AI cannot replicate.

Practical Approaches to Teaching Positionality

In this resource I’ll explore more examples of exercises I use in my classrooms to help students explore positionality. For now, I’ll share a few examples of simple yet powerful exercise that can allow students to understand their positionality and its relevance to knowledge production:

The Power Flower Exercise

This activity invites students to visually map their own social positions across multiple dimensions of identity (race, gender, class, ability, etc.), distinguishing between dominant and subordinate positions in each category. As they share these “power flowers” with classmates, students begin to see how different configurations of privilege and marginalization shape unique vantage points on the world.

Case Studies of Contested Knowledge

We examine research like Alice Goffman’s controversial ethnographic study “On the Run” (2014), exploring how her positionality as a white, educated woman studying Black communities influenced both her access to information and her interpretations of what she observed. Students debate questions like: What did her position allow her to see? What might it have obscured? How might the research have differed if conducted by someone positioned differently?

Collaborative Knowledge Production

Students work in diverse groups to develop understanding of complex issues, with explicit attention to how their varied social positions and lived experiences contribute different insights. They practice what bell hooks (1994) calls “engaged pedagogy,” where everyone contributes to the learning community from their unique standpoint.

AI Output Analysis

Students examine texts generated by AI on the same topic but with different prompts or parameters, analyzing how the outputs reflect particular perspectives and what assumptions they encode. This helps students see that AI tools, despite their computational nature, are not neutral or objective knowledge sources.

Conclusion: Toward Epistemic Justice

Teaching positionality is not about replacing the ideal of rigorous inquiry with relativism. Rather, it’s about creating conditions for more honest, careful, and just knowledge practices. As we integrate AI tools into our classrooms, this foundation becomes essential. Students who understand knowledge as positioned can navigate AI tools critically and creatively, using them to enhance rather than replace their own situated understandings.

When students recognize that their own positionality offers unique and valuable perspectives—perspectives that even the most sophisticated AI cannot replicate—they develop confidence in their contributions to knowledge. This is particularly crucial for students from backgrounds historically marginalized in academic spaces, whose ways of knowing have often been devalued or dismissed.

As Sultana (2007) reminds us, “The knowledges produced are hence located within the context of our subjectivities and intersubjectivities, and the spaces that we inhabit at that moment” (p. 380). By bringing this awareness into our engagement with AI tools, we can work toward what Paulo Freire (1970) described as authentic dialogue—where multiple ways of knowing are brought into conversation, creating possibilities for deeper understanding and more just futures.

References

Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books.

Bulhan, H. A. (2015). Stages of colonialism in Africa: From occupation of land to occupation of being. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 239-256.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Finlay, L. (2002). Negotiating the swamp: The opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice. Qualitative Research, 2(2), 209-230.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575-599.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Mauthner, N. S., & Doucet, A. (2003). Reflexive accounts and accounts of reflexivity in qualitative data analysis. Sociology, 37(3), 413-431.

Sultana, F. (2007). Reflexivity, positionality and participatory ethics: Negotiating fieldwork dilemmas in international research. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 6(3), 374-385.

Media Attributions

- drawing from gloriaindepth.tumblr.com