VADE MECUM (Come with Me)

The Latin Alphabet

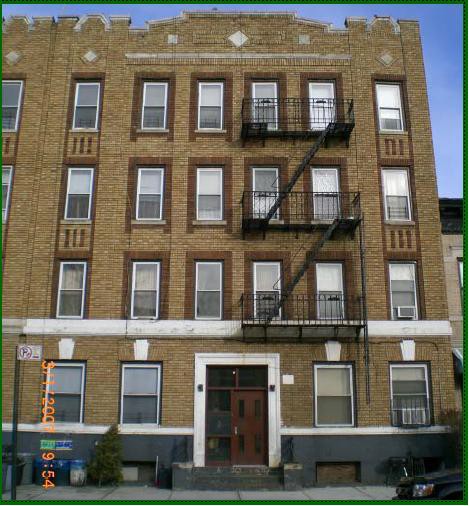

On the third day of my quarantine, as I lay in bed at night with a cough, difficulty breathing, fever, and no sense of taste or smell, I heard, or thought I heard, the door of my apartment swing open. From time to time, I had had hallucinations of visitors entering my room, weird but harmless ghosts, so I kept still beneath the covers, feeling invisible. Footsteps sounded in the kitchen, stopped, and resumed. A cabinet door opened; someone turned the faucet on and ran the water for a very long time, the way you do to bring cold water up from pipes deep underground. A cork popped, liquid filled a glass, and then the steps I heard were inside my room.

The woman at my bedside was both very old and very young. Without saying a word, she held the glass to my mouth. What I swallowed was sharp and fragrant, like wine with hints of herbs, citrus, and the sea. My attention was then drawn by a light; outside my window the sky was growing brighter. The dark violet of early dawn turned to day, then day brightened suddenly to noon, a deep sapphire cut by the rays of a blazing sun. Voices streamed in from outside, like a wind, a chorus of sounds: old women exchanging words with old men, people boasting, praying, threatening, muttering, meditating, singing at their work, young women shouting, whispering, calling to their friends, teenage boys chattering, rippling into laughter, little children running and screaming in excitement. The voices rose and fell in waves, stood apart and blended together, articulated contrasts, and fused into one.

It was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard.

One voice stood out from the rest. It was a child’s voice, though whether it was a boy’s or a girl’s, I couldn’t say. It kept calling me, saying my name three times, another three times, another three times. My name is a common one but when pronounced by the child it sounded like an angel’s nursery rhyme. The child stopped below my window, just out of sight, and shouted something to me with great urgency, a long sentence in a language I did not understand. Was the child in trouble? Was there something I needed to do? Or did it have something else to say, or to report? I thought if I could see the child’s face it would help me understand, but when I sat up, the vision broke, the darkness of the night rushed back, and the voices all disappeared.

My visitor was sitting in the corner of my bedroom, on the edge of a large chair, lit by a streetlight. She appeared elderly and very short. Her white hair was in a bun, but a few locks of thin hair spiraled over her temples. If you told me she was French or Spanish or Jewish or Lebanese, Romanian or Turkish or Greek, Libyan or Tunisian or Egyptian, I would have believed you. In hindsight I realized who she most reminded me of. Every day, the grandmother of the owner of the Italian market in my city visits his store to make an inspection. She argues and jokes with the staff, shakes her finger at them and gives out hugs, making them all more alert and more generous. My visitor bore a strong resemblance to her, only with wider, darker eyes – eyes that had been places, had seen many cities, and known the minds of many men and women.

“Thank you.” I said to her, setting the glass down. My thoughts were lucid and for the first time in days, I felt there was a center to my person. With more force in my voice, I repeated: “Thank you. Who are you?”

“I am… Who am I? Not nobody; I used to be somebody. I used to be the life of a community, of a people who lived between the mountains and the Mediterranean Sea. For thousands of years those people knew me, and I brought them together – even when they fought (and how they fought!) – I brought them together. Now I am retired; only a few persons know me. Even my sons and daughters rarely visit now. Perhaps they no longer know who I am? I look different, I have certainly changed, but only in the ways all people change as they age; I am still the same in my heart, right here. My name is Latinitas.” She put stress on the tin. “Some call me Latinity.”

“That crowd of people – did you hear those voices outside?” “Did they sound like this?” And she mimicked them, perfectly. “Yes!”

“They were the people I was talking about; they were my people, speaking their language, Latin.”

“Latin,” I repeated. “It’s a hard language. Do you speak it? Do you know it?” “Yes!” she laughed.

“You must be very smart.”

“I’ll tell you what, dear. I grew up in a very large family that lived in small villages near a river in Italy called the Tiber about three thousand years ago. We raised pigs and grew barley, wove cloth out of wool thread, quarried stone, dug ditches, made war, and loved. Some of us learned how to read and write, but hundreds of years would pass before any scholars or teachers came to live with us. Of course, I am smart; but not smart like you think. Smart like every human being who can pay attention is smart. Prūdēns, is what we call it.”

“Do you know what that child was saying?” “What child?”

“The child at the window.”

“If you saw something or heard something, only you saw it. I was sitting here, waiting in the dark for you to come around. The wine” – she held up the bottle – “it’s good, isn’t it? Old stuff.”

“The child was saying something to me, like…” A string of babble came out of my mouth. She looked at me and raised an eyebrow.

“You know the language,” I said pointedly. “Can you teach me enough to understand what I heard?”

“Maybe. I can teach, but it’s not easy to learn.”

“You said it was easy; you said, anyone who can pay attention can learn it.”

“It’s easy for a child, who has parents to take her around and point to things and say their names and teach her with care all the hours of the waking day; a child who lives in the world the language is meant to describe. It would be easier if you too were still a child and your mind still soaked things up like a sponge. Even so, it would take time, and you would be speaking like a toddler for several years. But now look at you: you are older, and your brain is packed full of things already, and you live in a world” – she pointed to my computer – “that is nothing like the world that Latin was built to describe. Besides: you are still very sick.”

“Your drink made me feel better.”

“Because it was a good vintage you drank, a very old one. But wait a half hour, and the effects, mostly, will be gone.”

“So, is there a book I can read that will teach me? When I’m feeling better?”

“No. You can’t learn a language by reading a book. Reading is for entertainment. How many things do you remember from the last book you read? Name seven words you learned! Recite the bits you learned by heart!” And she crossed her arms.

“Ah.” She calmed down. “You have always been so nice to my son. You bring his store so much business. Here…” She reached into her bag. “A gift. There is only one kind of book that will help you learn a language. This. Open it.”

I took the book she presented to me. I thought I would see pages full of rules and instructions, like a textbook. But every single page – from beginning to end – was completely blank.

“What’s this? There’s nothing here.”

“It’s what you need: paper. To write on. It’s not a book, because you have not written it yet. To learn, you will have to write it, and write it yourself. I will tell you what to write, what to put on the pages, every word even; but the work of writing by hand – that is yours. As you write, you will teach yourself; each time you return to it, you will teach yourself more. It will become your second brain, for a while, since your first brain is full; and then, with practice, your first brain will make a copy of it. When the book is done, and your brain has made its copy, you will have learned enough of the language that you can begin to understand that voice that you heard, whatever it was saying. Ok?”

I took one more drink of the wine and water. Once again it stirred my spirits, but the sky remained dark, the night punctuated by a distant siren.

“Alright.” I squinted at the lamp as I reached for a pen. “Alright. Tell me what I should write. I want to see what it’s like. Show me.”

“It’s not so easy. Dī immortālēs! Call on the immortal gods for strength first! But you don’t even know how to do that correctly. So I’ll offer you this advice. If I talk too fast, stop me, and I will repeat what I said, and let you catch up. If you find it hard, drink some more, and wait until you feel ready again. When the glass is empty and your focus fades away, we will have to stop. It’s

only wine and water, not a cure. There is no magic for the body in this world, only magic for the soul. But we can start again, another day, and carry on the day after that, and the day after that, until the book is full.”

“Are you ready?”

ll language is divided into sounds. The smallest sounds are represented by letters. All the letters together form an alphabet. The Latin alphabet was borrowed from the Greek alphabet, just as the Greek alphabet was borrowed from the alphabet of the

Phoenicians, who lived in what today is called the country of Lebanon.”

“The original Latin alphabet only had capital letters. There were 23 letters, like this…”

– she inscribed them carefully into the air –

A B C D E F G H I K L M N O P Q R S T V X Y Z (A)

“There was no letter J, no letter W, and no letter U. Modern printers use capital letters and lower-case letters to print Latin. They also use the letter U, which was added in the 1300s, to distinguish the vowel sound that was previously represented by V. (The letter V originally could represent both a vowel and a consonant.)”

Remind me what that is, I said. A vowel?

“A Vowel is a sound made with your mouth open and fixed. Vowels you can sing, like ‘o’: ooooo. There are six vowels in Latin. Each vowel comes in two kinds: short, and long. The short vowels are pronounced the way Spanish and Italian speakers pronounce their vowels. The long vowels of Latin were pronounced the same way, but were held a fraction of a second longer. In books for beginners, long vowels have a line called a Macron or Long Mark over them (Macron is the Greek word for ‘long’).”

Vowels: Short and Long

Short vowels sound like: (B) Long vowels sound like: (C)

a A alike ā Ā father

e E get ē Ē they

i I tin ī Ī unique

o O hot ō Ō obey

u U put ū Ū rude

y Y über y Y über

“The vowel y Y is used for Greek words (the Greek letter is called ypsilon).” “Now, two short vowels can combine to make a Diphthong.”

I repeated the word: ‘Diff-thong’.

“Spelled d-i-p-h-t-h-o-n-g. A diphthong is the sound made by two vowels that blend together. There are five diphthongs in Latin. They sound like this:”

The Diphthongs (D)

ae like aisle

a like out

ei like eight

eu like mew (EH-OO) oelike oil

ui like Louis (OO-WEE)

“The other letters in the alphabet are Consonants. A consonant is a sound formed with some part of your mouth fully or partially closed. Most consonants have a similar pronunciation in Latin and English. After I give the sound for each letter, say the Latin word:”

Consonants: Latin Letters, Pronunciation (E)

Letter Latin Pronunciation Definition

B as in bau “That’s the sound a dog makes.”

C as in cēdō “I go. Always pronounce like ‘k’, unless it’s Church Latin.”

D as in doceō “I teach.”

F as in fac “Make!”

G as in gaudē “Rejoice!”

H as in hoc “This thing.”

I as in iam “Already… An ‘i’ at the start of a word before another vowel is pronounced as a consonant, ‘y’.”

K as in kalends “The first day of the month.”

L as in laudā “Praise!”

M as in mihi “To me.”

N as in nōn “Not.”

P as in placēbō “I will please.”

Q as in quid? “What?”

R as in rogābō “I will ask. Pronounce your ‘r’ lightly, like in Spanish or Italian.”

S as in sum “I am.”

T as in taceō “I am silent.”

V as in vidēbam “I saw. Always pronounce Latin ‘v’ like ‘w’, unless it is Church Latin.”

X as in Xerxēs “The Persian king.”

Z as in Zephyrus “That’s the ancient name of the west wind.”

“The consonant q is always followed by u, like in English, and the combination is pronounced like it is in English, too: quaerō, ‘I seek’.”

“Latin also has three pairs of consonants that are only used to represent Greek words.”

The Greek consonant pairs: (F)

PH as in philosophia ‘philosophy’

TH as in theologia‘ theology’

CH as in Chīrōn ‘Chiron, the wisest of the Centaurs’”

Roman Numerals

“Now that you have that all written down, write down the Latin numbers, which are represented by capital letters like this:”

Roman Numbers (G)

I is one

V is five

X is ten

L is fifty

C is one-hundred

D is five-hundred

M is a thousand

To read a Latin number, simply add up the parts, which go from the largest to the smallest, left to right. However, if a smaller unit comes before a larger unit, to its left, the smaller unit has to be subtracted from it. This is how the math works.”

She wrote some examples in the air with her finger:

VII is…5 plus 1 plus 1, or 7 (H)

IV is…5 minus 1, or 4

XXI is…10 plus 10 plus 1, or 21

XL is…50 minus 10, or 40 “There is one more thing.”

“English words have stresses in different parts, like this: BUBble. InFECtion. SUPerman.”

“Latin has stresses too. To learn where the stress goes, first pronounce a word, and count how many vowel sounds or diphthongs are in it. This is the number of Syllables it contains.”

“When there is just one syllable, that vowel or diphthong gets the stress – very simple. When there are two syllables, the first one always gets the stress, like BUBble – very simple:”

Syllable Stress: One and Two Syllable words

Examples

|

One syllable: it gets stressed (H) quis who? et and mors death |

Two syllables: the first gets stressed (I) salvē SALvē hello! ūnus Ūnus one morbus MORbus disease eae Eae they |

Three or More Syllable Words

“When there are three or more syllables, look at the second-to-last syllable. If it has a long vowel, a diphthong, or a short vowel followed by two consonants, it is stressed like ‘inFECtion’ in English.”

If the Second-to-last syllable has a long vowel, a diphthong, or a short vowel followed by two consonants: (J)

erāmus erĀmus (ā is a long vowel) we were

habēre habĒre(ē is a long vowel) to have

Mīnōtaurus MīnōTAUrus (au is a diphthong) Minotaur, mythical monster

servāvistī servāVIStī (short i + two consonants) you saved

adulescēns adulEScēns young adult

vendidisse vendiDISse to have sold

“If the second-to-last vowel is a short, followed by ONE consonant or another vowel, the emphasis moves back to the third-to-last syllable, and you pronounce it like SUPerman:”

Second-to-last is short followed by vowel: (K)

audiō AUdiō I hear

patria PAtria homeland

negōtium neGŌtium business

Second-to-last is short followed by one consonant: (L)

erimus Erimus we will be

crēdidī CRĒdidī I believed

geminī GEminī twins

“Now practice. Read this poem. If you read all of this out loud three times, I will return tomorrow, and we will go on an explōrātiō, an adventure.”

And she left. Through my window I then saw her walking down the street. Outside she seemed much taller. As she approached the corner, she had grown so much that she appeared just as tall as some of the buildings. She got larger and larger the further away she was, until at last, even though her feet were still on the ground, her head appeared to brush the sky.

I was fading now. I read the poem she gave me out loud, but before I could finish reading it a third time, I fell fast asleep:

Carmina Burana excerpt

Ō quam fēlīx est antidotum sopōris,

quot cūrārum tempestātēs sēdat et dolōris!

Dum surrēpit clausīs oculōrum porīs,

ipsum gaudiō aequiperat dulcēdinī amōris.