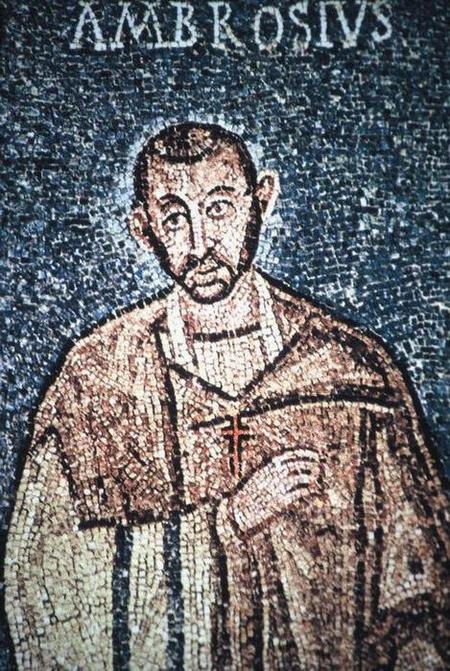

72. A mosaic from the church of St. Ambrogio in Milan showing Ambrose himself. Virīs sīcut Ambrosiō, Symmachō, Petrōniō et aliīs erant nōmina Graeca cum cāsibus Latīnīs. Men like Ambrosius, Symmachus, Petronius and others had Greek names with Latin case-endings. Migration, intermarriage, and even the cruel institution of slavery made the inhabitants of the Roman empire increasingly cosmopolitan as time passed. This cosmopolitanism also made it easier for Christianity to spread quickly.

Explōrātiō Trīcēnsima Tertia (XXXIII) Adventure Thirty-Three

Saint Ambrose, Deus Creātor Omnium

The Indefinite Pronoun quīdam, quaedam, quoddam

Special Translation of the Optative Subjunctive

Special Translation of the Potential Subjunctive

Special Translation of the Deliberative Subjunctive

Augustine, Dē Magistrō, Excerpt

Where and When Are We Today?

Mediōlānum, Ītalia

Mēnsis Māia

Flāviō Arcadiō Augustō Flāviō Bautōne cōnsulibus

Milan, Italy

May, 385 CE

Did I tell you about the day I watched Saint Augustine and his son play ball? It is one of the visits I remember most clearly.

I could immediately tell that Milan, the city we were visiting, had turned Christian from the number of crosses visible in public and the absence of statues representing the traditional gods and goddesses. Styles had changed too, in dozen of obvious and not-so-obvious ways. Take paintings, for example. The color palette of the late Republic and early empire, with its brilliant blues and reds and greens and yellow, was gone, as pigments were becoming more expensive and harder to acquire. The figures of men and women you saw in paintings now were more grave, less playful, more soulful, their eyes so intense they were sometimes hard to look at. Haloes were a common sight on pictures of saints and famous holy figures. The clothes worn by officials were more elaborate and heavy, and, at least in Milan, incorporated furs – a northern European touch. Some Italians had also borrowed the habit of wearing moustaches from German peoples like the Goths.

Starting from the forum of Milan Latinitas took me down a busy street to what looked like a basilica. This was in fact a Christian church that had recently been dedicated by the local bishop, a man known to later ages as Saint Ambrose. We went inside and saw an old man refilling the oil in the lamps while a choir of singers practiced a hymn. The text of the hymn, which Ambrose had composed, began like this:

Saint Ambrose, Deus Creātor Omnium

Deus, creātor omnium,

polīque rēctor, vestiēns

diem decōrō lūmine,

noctem sopōris grātiā,

artūs solūtōs ut quiēs

reddat labōris ūsuī,

mentēsque fessās allevet,

lūctūsque solvat anxiōs…

God, creator of all things,

ruler of the sky, dressing

day with a suitable light,

and night with the grace of sleep,

so that rest can restore relaxed

limbs for the use of work,

and soothe weary minds,

and dissolve anxious grief…

We left the church by a rear exit and walked from there into a garden where we encountered a man and a teenage boy throwing a stuffed leather ball back and forth while they talked. Two women were watching them play, one who was about Augustine’s age sitting on a stool in a doorway, the other, who seemed older, looking down from a second-storey window in an adjacent building. We sat down under a blossoming pear tree to study, and Latinitas identified the four persons.

Augustine

“That is Aurēlius Augustīnus, or Augustine. He is from the town of Hippo in North Africa. Rather like Cicero, he rose to prominence based on his skill as an orator and philosopher. Up until now he has worked as a teacher of rhetoric, first in Carthage, then in Rome, where he was mentored by Symmachus. He did not like Rome – the students kept stiffing him when it was time to pay their tuition fees – but was fortunate enough to get Symmachus to recommend him for a position here in Milan.”

I thought Symmachus was a pagan?

“He is, but Augustine is, at the moment, a follower of the Persian prophet Mani. Members of this religion, called Manicheans, are dualists who believe the Mani’s revelation fulfilled and superseded the teachings of Zoroaster, Jesus, and the Buddha. Symmachus does favors for the Manicheans whenever he can because, like him, they are not Christians. But Augustine, next year, will convert to Christianity, under the inspiration of Ambrose.”

Who is the woman on the stool?

“That is Augustine’s partner, the mother of his son. Her name is not recorded, and so I am not allowed to share it with you. The old woman in the window is Augustine’s mother Monica, who is a Christian.”

What about the boy?

“That is Augustine’s son, Adeodatus. The name, if you unpack it, means ‘Gift of God’, literally ‘Given by God’: ā Deō datus. He is about fifteen years old.”

“We will come back to them later, after we have done our lesson.”

The Indefinite Pronoun quīdam, quaedam, quoddam

“There is a common indefinite pronoun and adjective quīdam, quaedam, quoddam which means ‘certain’. It is formed by combining the relative pronoun quī, quae, quod with the ending -dam. When the form of quī ends with the letter -m, it changes to -n:”

Forms of the Indefinite Pronoun and Adjective quīdam, quaedam, quoddam

| Singular | Singular | Singular | Plural | Plural | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | M. | F. | N. | M. | F. | N. |

| Nom. | quīdam | quaedam | quoddam | quīdam | quaedam | quaedam |

| Gen. | cuiusdam | cuiusdam | cuiusdam | quōrundam | quārundam | quōrundam |

| Dat. | cuidam | cuidam | cuidam | quibusdam | quibusdam | quibusdam |

| Acc. | quendam | quandam | quoddam | quōsdam | quāsdam | quaedam |

| Abl. | quōdam | quādam | quōdam | quibusdam | quibusdam | quibusdam |

Vocabulary

Indefinite Pronoun and Adjective

| Latin Pronoun/Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| quīdam, quaedam, quoddam | certain; some(one); some(thing) |

Exercises 1-2

1. In cīvitāte Antiochīā rēx fuit quīdam nōmine Antiochus, ā quō ipsa cīvitās nōmen accēpit Antiochīa.

2. Post mē erat Aegīna, ante mē Megara, dextrā Piraeus, sinistrā Corinthus, quae oppida quōdam tempore flōrentissima fuērunt.

“flōreō, flōrēre, flōruī means ‘to flourish’.”

Indirect Questions, Continued

“Now we’ll continue with a review of indirect questions (see Explōrātiō 30). First, let’s practice with the formation of subjunctive verbs.”

Drill

“Give the third-person singular, active voice forms of the present, imperfect, and pluperfect subjunctive for the following verbs:”

| Latin Verb | Present Subjunctive 3rd sing. active | Imperfect Subjunctive 3rd sing. active | Pluperfect Subjunctive 3rd sing. active |

|---|---|---|---|

| vocō, vocāre, vocāvī, vocātus | |||

| videō, vidēre, vīdī, vīsus | |||

| dīcō, dīcere, dīxisse, dictus | |||

| veniō, venīre, vēnī, ventus | |||

| sum, esse, fuī, futūrus |

“An indirect question is any question that appears in a subordinate clause. The verb in an indirect question is subjunctive but it does not call for a special translation. An indirect question starts with an interrogative of some kind. To review, the most common interrogatives are:”

Review of Interrogative Words

Forms of the Pronoun quis, quid (singular)

| Case | Latin Pronoun (m., f.) | English Meaning | Latin Pronoun (n.) | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | quis | who? | quid | what? |

| Genitive | cuius | whose?; of whom? | cuius | of what? |

| Dative | cui | to/for whom? | cui | to/for which? |

| Accusative | quem | whom? | quod | what? |

| Ablative | quō | prep. + whom? | quō | prep. + what? |

“The plural forms of the pronoun quis, quid are identical with the plural forms of the interrogative (and relative) quī, quae, quod. As an interrogative, quī quae, quod mean ‘which’, or ‘what’, as in quī vir...? ‘what man...?’

Forms of the Interrogative (and Relative) quī, quae, quod

| Singular Masc. | Singular Fem. | Singular Ntr. | Plural Masc. | Plural Fem. | Plural Ntr. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | quī | quae | quod | quī | quae | quae |

| Gen. | cuius | cuius | cuius | quōrum | quārum | quōrum |

| Dat. | cui | cui | cui | quibus | quibus | quibus |

| Acc. | quem | quam | quod | quōs | quās | quae |

| Abl. | quō | quā | quō | quibus | quibus | quibus |

Interrogative Adverbs

“Here are some interrogative adverbs that you’ve learned. Note that some of these words have other uses: for example, quam can also mean ‘than’ in a comparison, or it can be the relative pronoun.”

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| cūr | why? |

| quam | how; “With an adjective, like quam fēlīx ‘how lucky’” |

| quandō | when? |

| quantum | how much? |

| quārē | how?; why? |

| quemadmodum | how? |

| ubi | when?; where? |

| unde | from where? |

“And here are three new ones to add to your vocabulary:”

Vocabulary

Interrogative Adverbs

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| quō | for which reason?; to what end?; to what place? |

| quōmodo | how? |

| utrum | whether? |

Exercises 3-5

3. Audīre ex tē volumus ubi sīs et utrum veniās.

4. Vidēs, igitur, quōmodo animus inveniat aliquid voluptātis etiam inter difficilia.

5. Quārē numquam ad āram sacram accessissētis mīrābāmur.

The Optative Subjunctive

“Yesterday you learned that the subjunctive can be used as the main verb of a sentence, in an independent clause. The first such use you learned is the jussive subjunctive, which is used to give a command or exhortation. Another use of the subjunctive as the main verb is the optative subjunctive. The optative subjunctive expresses a wish for something to happen in the future, or a wish for something to have happened that did not. A sentence with an optative subjunctive is often introduced by utinam ‘if only...!’. If the optative subjunctive is negated it is introduced by nē or utinam nē.

Vocabulary

Adverb

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| utinam | if only...! |

Special Translation of the Optative Subjunctive

“The translation of the optative subjunctive depends on the tense. A present subjunctive after utinam can be translated ‘would verb’, after utinam nē ‘would not verb’. If utinam is not present, translate the present subjunctive ‘may [subject] verb!’. If the negative nē alone introduces it, translate the present subjunctive ‘may [subject] not verb!’. The imperfect and pluperfect subjunctive after utinam can be translated like the indicative, ‘were verbing’, and ‘had verbed’; after utinam nē, ‘were not verbing’, ‘had not verbed’.

Optative Subjunctive Examples

Nē vīvam sī hoc sciō!

May I not live if I know this!

vīvam (present subjunctive) is optative; it is negated by nē

Stet haec urbs!

May this city stand!

stet (present subjunctive) is optative

Utinam rēs pūblica stetisset!

If only the republic had stood!

stetisset (pluperfect subjunctive) is optative; it is introduced by utinam

Utinam nē vērē scrīberem!

If only I were not writing the truth!

scrīberem (imperfect subjunctive) is optative; it is introduced by utinam and negated by nē

Exercises 6-9

6. Et dīxit Apollōnius: ‘pereat haec cīvitās!’

7. Sit tibi terra levis.

“A phrase often found on tombstones.”

8. Utinam mē mortuum prius vīdissēs aut audissēs!

9. Utinam illum diem videam cum tibi agam grātiās quod mē vīvere coēgistī!

“Cicero, in a letter to his friend Atticus.”

The Potential Subjunctive

“Another use of the subjunctive as the main verb of a sentence is the potential subjunctive. A potential subjunctive expresses a possibility. If the possibility is negated, the negative nōn is used.

Special Translation of the Potential Subjunctive

“The translation of the potential subjunctive depends on the tense. A present subjunctive can be translated ‘[subject] may / might / could verb’. The imperfect subjunctive can be translated ‘[subject] might have / could have / would have verbed’. The imperfect subjunctive usually implies that the possibility was not fulfilled. The pluperfect subjunctive is rare in this use.

Potential Subjunctive Examples

Quis dīcat hoc negōtium rēctum esse?

Who could say that this business is right?

dīcat (present subjunctive) is potential

Dīcerēs hoc negōtium haud rēctum esse.

You would have said that this business was by no means right.

dīcerēs (imperfect subjunctive) is potential

Exercises 10-12

10. Putēs istum senem fēlīcissimum esse.

11. Nunc aliquis dīcat mihi, ‘Quid tū? Nūllane habēs vitia?’ “Horace.”

12. Cuperem vultum vidēre tuum, cum haec legerēs. “Cicero to Atticus again.”

The Deliberative Subjunctive

“Finally, when a subjunctive is the main verb in a direct question, it is likely a deliberative subjunctive. The deliberative subjunctive poses a question when the speaker is uncertain and asks what should be done. If the deliberative subjunctive is negated, the negative nōn is used.

Special Translation of the Deliberative Subjunctive

“The translation of a deliberative subjunctive depends on the tense. The present subjunctive can be translated ‘should [subject] verb?’. The imperfect subjunctive can be translated ‘should [subject] have verbed?’.”

Deliberative Subjunctive Examples

Eāmusne ad oppidum?

Should we go to town?

eāmus (present subjunctive) is deliberative

Haec cum vidērem, quid agerem?

When I saw this, what should I have done?

agerem (imperfect subjunctive) is deliberative; (vidērem is imperfect subjunctive in a cum-clause)

Exercises 13-16

13. Quem nunc vocēmus? Unde auxilia peterēmus?

14. Periī! Quō curram? Quō nōn curram?

15. Quid ego faciam? Maneam an abeam?

16. Rogēmusne istōs quōmodo hās rēs gerī velint?

At that moment Augustine missed a catch and the ball rolled to my feet. Tolle, Latinitas whispered to me, pick it up. I picked it up and nervously tossed it back to him, adding Haec est tibi. He acknowledged me with a nod and went back to his game.

“Now, here is your vocabulary for today.”

Vocabulary

Deponent A-Verb (First Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| arbitror, arbitrārī, arbitrātus sum | to consider; suppose; judge |

E-Verb (Second Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| cēnseō, cēnsēre, cēnsī, cēnsus | to assess; judge; propose |

I-Verbs (Third Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| addō, addere, addidī, additus | to add |

| canō, canere, cecinī, cantus | to sing |

| occurrō, occurrere, occurrī, occursus + dat. | to meet; come to; occur to |

| trahō, trahere, traxī, tractus | to draw; drag |

Mixed I-Verb (Third Conjugation -iō)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| efficiō, efficere, effēcī, effectus | to effect; bring about “This verb often introduces a substantive ut clause of result.” |

Fourth Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| sonus, sonūs | m. | sound; noise |

US-A-UM Adjective (First and Second Declension Adjective)

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| rārus, -a, -um | rare; few; scattered |

Conjunctions

| Latin Conjugation | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| at | but; but yet |

| quoniam | since |

| utrum / -ne ... an | (whether)… or |

| vel | or |

| vel… vel | either… or |

Adverbs

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| interdum | occasionally |

| prōrsus | absolutely |

| sānē | really; surely |

Exercises 17-23

17. Nē ad malum hoc addāmus malum.

18. Maneantne nōbīscum an domum eant?

19. Arbitrātus est eōs vel bellō vel pācī parātōs.

20. Quoniam ita tū vīs, nāvēs ad lītus trahāmus.

21. At cēnseō ut cōpiae nostrae statim proficīscantur et hostēs rārōs oppugnent.

“The verb oppugnō, oppugnāre, oppugnāvī, oppugnātus means ‘to attack’.”

22. Haud sānē intellegō quid sit quod laudandum arbitrātur.

23. Mihi occurrit hoc: interdum aliquis sonus efficit ut canere velīmus et prōrsus tacēre nōn possīmus.

Augustine, Dē Magistrō

When we were done with our practice we began to listen to the conversation between Augustine and Adeodatus. It had the same rhythm as their game: each one would say something, then throw the ball. They were talking about philosophy, about the nature of language in particular. It was a long conversation, but the part we heard is preserved in a dialogue Augustine wrote many years later called Dē Magistrō, “On the Teacher.”

Augustine, Dē Magistrō, Excerpt

1) Augustinus: Quid tibi vidēmur efficere velle, cum loquimur?

Adeodātus: Quantum quidem mihi nunc occurrit, aut docēre aut discere.

Augustinus: Ūnum hōrum videō et assentior: nam loquendō nōs docēre velle manifēstum est; discere autem quōmodo?

Adeodātus: Quō tandem cēnsēs, nisi cum interrogāmus?

quantum here, ‘as far as’

assentior, assentīrī, assēnsus sum to agree

manifēstus, -a, -um obvious

interrogō, interrogāre, interrogāvī, interrogātus to ask a question

2) Augustinus: Etiam tunc nihil aliud quam docēre nōs velle intellegō; nam quaerō abs tē, utrum ob aliam causam interrogēs, nisi ut eum, quem interrogās, doceās, quid velīs.

Adeodatus: Vērum dīcis.

Augustinus: Vidēs ergō iam nihil nōs locūtiōne nisi ut doceāmus appetere.

Adeodatus: Nōn plānē videō; nam sī nihil est aliud loquī quam verba prōmere, videō nōs id facere, cum cantāmus. Quod cum saepe sōlī facimus nūllō praesente quī discat, nōn putō nōs docēre aliquid velle.

abs = ab

locūtiō, locūtiōnis, f. speaking; discourse

appetō, appetere, appetīvī, appetītus to strive for

plānē plainly; clearly

prōmō, prōmere, prōmpsī, prōmptus to produce; bring forth

cantō, cantāre, cantāvī, cantātus ~ canō, canere, cecinī cantus

cum ... sōlī supply the verb sumus

praesēns, praesentis present

quī discat ‘to learn’

3) Augustinus: At ego putō esse quoddam genus docendī per commemorātiōnem, magnum sānē, quod in hāc nostrā sermōcinātiōne rēs ipsa indicābit. Sed sī tū nōn arbitrāris nōs discere, cum recordāmur, nec docēre illum, quī commemorat, nōn resistō tibi, et duās iam loquendī causās cōnstituō, aut ut doceāmus aut ut commemorēmus vel aliōs vel nōs ipsōs, quod etiam, dum cantāmus, efficimus; an tibi nōn vidētur?

Adeodatus: Nōn prōrsus; nam rārum admodum est, ut ego cantem commemorandī mē grātiā, sed tantummodo dēlectandī.

commemorātiō, commemorātiōnis, f. recollection

sermōcinātiō, sermōcinātiōnis, f. conversation

indicō, indicāre, indicāvī, indicātus to show; indicate

recordor, recordārī, recordātus sum to recall

commemorō, commemorāre, commemorāvī, commemorātus to remind

resistō, resistere, restitī + dat. to resist

admodum very

tantummodo only

dēlectō, dēlectāre, dēlectāvī, dēlectātus to delight

4) Augustinus: Videō quid sentiās. Sed nōnne attendis id, quod tē dēlectat in cantū, modulātiōnem quandam esse sonī? Quae quoniam verbīs et addī et dētrahī potest, aliud est loquī, aliud cantāre; nam et tībiīs et citharā cantātur, et avēs cantant, et nōs interdum sine verbīs mūsicum aliquid sonāmus, quī sonus ‘cantus’ dīcī potest, ‘locūtiō’ nōn potest; an quicquam est, quod contrādīcās?

Adeodatus: Nihil sānē.

attendō, attendere, attendī, attentus to notice; pay attention to

cantus, -ūs, m. song; music

modulātiō, modulātiōnis, f. modulation; melody

dētrahō, dētrahere, dētraxī, dētractus the prefix dē- adds ‘away’ to the verb’s meaning

tībia, a-e, f. pipe

cithara, -ae, f. cithara; lyre (a stringed instrument)

avis, avis, f. bird

mūsicus, -a, -um musical

sonō, sonāre, sonuī to make a sound

contrādīcō, contrādīcere, contrādīxī, contrādictus to contradict; say contrary

The Dē Magistrō may not be Augustine’s most famous work, but it is quite profound as a piece of philosophy; it considers why the sounds we make when we speak actually cause others to think of certain ideas. Much more famous for most people are Augustine’s Cōnfessiōnēs, his spiritual autobiography, and his Cīvitās Deī, which he wrote as an old man after Rome was sacked by Alaric. It is a very long book, arguing, in a sense, that the only real city in the universe is the eternal ‘city’ ruled by God.

Latinitas finished our visit with this spoiler.

“A year from now, Augustine’s partner will go back to Carthage and leave Augustine and Adeodatus here. Monica has arranged for her son to be married to a Catholic woman from Milan whose connections will help advance his career, and that arrangement means the end of his informal relationship. In addition, Augustine will finally convert to Christianity. He has a long and distinguished career ahead of him. Sadly, Adeodatus will die young, just a few years from now. The dialogue he wrote was a tribute to his beloved son.”

73. Saint Augustine in his Study, by Vittore Carpaccio, 1508. Carpaccio has equipped the saint’s study with all items that a pious scholar from the fifteenth century would like to have in their room, such as a private altar for worship and fancy bookholders (not to mention a small German lapdog). In eōdem modō nōs quoque facere amāmus ut hominēs antīquī nōbīs videantur similēs. In the same way we too like to bring it about that figures from the past appear similar to ourselves.