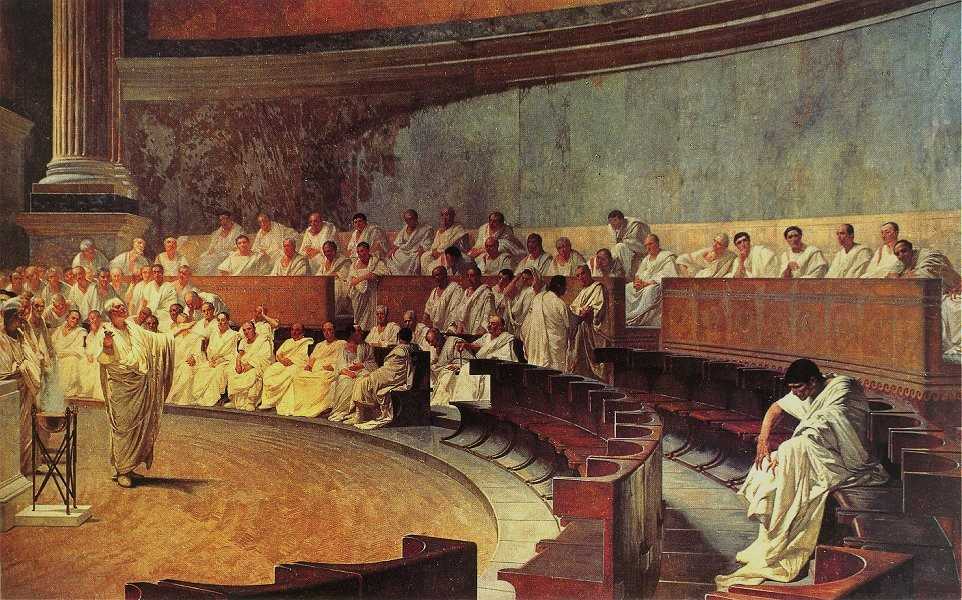

10. Cicero Denounces Catiline, by Cesare Maccari (1889). The senātus of Rome met in buildings that were linear and square, not round. In Cicero’s day there were approximately nine-hundred men who counted as senators, of which one- or two-hundred might actually attend meetings.

Explōrātiō Quīnta (V) Adventure Five

Vocabulary: Third Declension Nouns

Genitive Singular Endings, Declensions 1-5

Drill: Genitive and Accusative Singular Forms

Translating a Sentence with a Preposition

Where and When Are We Today?

Campus Mārtius, Rōma

Mēnsis November

M. Tulliō Cicerōne C. Antōniō Hybridā cōnsulibus

Campus Martius, Rome

November, 63 B.C.E.

“Before we travel today,” Latinitas said to me, “we will have to dress up. Or at least I will; you can continue to wear that old purple bathrobe of yours, since it lets you pass for a child of royalty visiting from a foreign land. But we are going to a meeting of the senātus today, amidst a national emergency, and in that environment a grown woman is going to attract too much notice if she can’t pass for a Roman matron or Vestal Virgin.” As she spoke, she covered her hair with a golden hairnet; when she was satisfied that it was in place, she threw a woolen mantle with an intricate floral pattern over her head and wrapped it across her shoulders.

Cicero, First Catilinarian

A sip of liquid transported us again. We were standing in the back room of a large temple; it was night, and by the light of torches and oil lamps I could clearly make out the head of a statue. It represented Iūppiter, Jupiter, king of the gods. According to Latinitas it was supposed to be Iūppiter Stator, The Jupiter Who Stops. It was dedicated by Romulus, the founder and first rēx of Rome, after a battle in which Jupiter supposedly halted the advance of the enemy Sabines. (Latinitas claims she was present at the battle and saw Jupiter in action; I have no reason to doubt her.)

The main area of the temple was crowded with Roman senators standing in small groups; they were discussing something with great earnestness, and many looked upset. The entrance of another party of men caused them all to turn and take notice. A band of stout-looking bodyguards parted to let a less muscular but more charismatic middle-aged man pass through the crowd. “Ecce, ille Cicerō, behold, the famous Cicero!” she whispered to me. A few senators tried to get Cicero’s attention but he ignored them, walking with his head down and his eyes almost closed, as if he was in a trance. He stopped next to a very fine-looking chair with ivory inlay – the consul’s chair – and raised his head, shooting a piercing glance at one senator who stood apart from the rest. Senators turned to him to listen. The orator took a deep breath through his nose and raised both manūs into the air; then, with a clear and powerful vōx, he unleashed a furious barrage of rhetorical questions directed at the isolated senator:

Cicero, First Catilinarian Excerpt

1) Quō usque tandem abūtere, Catilīna, patientiā nostrā? Quam diū etiam furor iste tuus nōs ēlūdet? Quem ad fīnem sēsē effrēnāta iactābit audācia? Nihilne tē nocturnum praesidium Palātī, nihil urbis vigiliae, nihil timor populī, nihil concursus bonōrum omnium, nihil hic mūnītissimus habendī senātūs locus, nihil hōrum ōra vultūsque mōvērunt?

For how long will you keep abusing our patience, Catiline? How long will that madness of yours, furor iste tuus, make fun of us? To what end will your unhinged audacity throw itself around? Has the security on the Palatine done nothing, the watchmen of the city done nothing, the fear of the people done nothing, the gathering of all good men done nothing, this heavily fortified place for a Senate meeting done nothing, the faces and expressions of these men done nothing to move you?

2) Patēre tua cōnsilia nōn sentīs, constrictam iam hōrum omnium scientiā tenērī coniūrātiōnem tuam nōn vidēs? Quid proximā, quid superiōre nocte ēgeris, ubi fueris, quōs convocāveris, quid cōnsiliī cēperis, quem nostrum īgnōrāre arbitrāris?

Do you not sense that your plans are laid open, do you not now see that your conspiracy is already hemmed in and held in by the knowledge of all these men? What you did last night, what you did the night before, where you were, who you invited, what plans you made – do you think any of us are ignorant of this?

3) Ō tempora, ō mōrēs! Senātus haec intellegit. Cōnsul videt; hic tamen vīvit. Vīvit? Immō vērō etiam in senātum venit, fit pūblicī cōnsiliī particeps, notat et dēsignat oculīs ad caedem ūnum quemque nostrum.

O what times, what behavior! (Ō tempora, ō mōrēs! )The Senate understands this. The consul sees it, (cōnsul videt.) Nevertheless, this man lives. Lives? As a matter of fact, he even comes into the Senate, takes part in public deliberation, marks out and designates each one of us for slaughter with his eyes.

4) Nōs autem fortēs virī satis facere reī pūblicae vidēmur, sī istīus furōrem ac tēla vītēmus. Ad mortem tē, Catilīna, dūcī iussū cōnsulis iam prīdem oportēbat, in tē conferrī pestem, quam tū in nōs omnēs iam diū māchināris.

Meanwhile we, who are brave men, think we have done enough for the republic if we should happen to avoid this man’s madness and spears. To death, Catiline, you should have been led a long time ago, on the consul’s order, and the destruction which you have for so long been plotting against all of us should have been directed at you.

The vōx of Cicero was still echoing through the interior of the temple when we slipped out, taking care to avoid the eyes of the security patrol. Latinitas commented on what I had just heard.

“You have just witnessed that rarest of things in politics, someone of great ambition confronting an overwhelming crisis and rising fully to the occasion. In a way he spent his entire career preparing for this moment. Unlike most Roman statesmen and politicians, Mārcus Tullius Cicerō did not come from an old aristocratic family or achieve fame after rising through the ranks in the army. He was brought up in a tiny town in the mountains of Italy called Arpinum; his father gave him the best education he could afford, and Cicero used it to hone to perfection a great natural talent for public speaking. After starting out as a defense lawyer and winning many difficult cases, he went into politics, where his skills as a speaker and constant hustle eventually put him in the consul’s chair.”

“Over the decades he has faced many personal risks and acquired many opponents and rivals. Yet he has never been in more danger than now, during this his consulship. Lūcius Sergius Catilīna, the senator we saw him attacking, has gathered together a large and diverse band of people who are willing to join a conspiracy to massacre the leadership of Rome and overthrow the state. Cicero recognizes his enemy’s strengths – Catiline is charming, daring, and smart. He knows that Catiline’s supporters include desperate people who nourish legitimate grievances against the powers that be. He understands and will take into account all these factors in the speech he is giving now and those he will give in the next few days, which will mark the beginning of Catiline’s downfall.”

“Cicero is making one mistake, though. He believes that eliminating the leadership of the revolutionary movement will be enough to restore stability and peace to the Republic. He does not appreciate the fact that, if nothing is done to remedy the economic desperation that makes people willing to try revolution, the instability and violence will only continue. And so it shall.”

A makeshift tent stood on the grounds outside the temple, lit by a lamp from within. Inside a servant of Cicero’s sat reviewing a text: the text of his speech, which the orator had memorized. Latinitas asked if she could look at it. Without even glancing up at her he said, ‘Go home, old lady, and spin your wool; this is work for men.’

All at once a change came over Latinitas. She grew very tall again – just like the first night I met her, after she left – and her garments and skin took on a weird glow. Her eyes were fiery and her gaze was absolutely unbearable; I looked away. With a voice drawn from somewhere deep in the heart of the world she repeated her request for the text: Dā mihi, give it to me.

I heard Cicero’s secretary humble himself in terror and scamper away. When I looked up again, Latinitas was standing there examining the book as if nothing had happened, her old self again. I didn’t ask what had taken place; I knew what it meant, no doubt about it. It is heartening to have a dea as your Latin teacher, but it can also be, at times, very frightening.

“Look here!” she said, marveling at the text. “Such words! Audācia, furor, timor, boldness, madness, fear.... Verbs are words for actions, but nouns, the names of persons and things, can be just as powerful.”

“If I teach you something important about nouns, do you think you can remember?”

Was this a threat? I nodded yes.

“Excellent.”

Third Declension Nouns

Vocabulary: Third Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| lībertās, lībertāt-is | f. | freedom |

| mors, mort-is | f. | death |

| urbs, urb-is | f. | city |

| lēx, lēg-is | f. | law |

| vōx, vōc-is | f. | voice; word |

| rēx, rēg-is | m. | king |

| mōs, mōr-is | m. | custom (singular); behavior (plural) |

| furor, furōr-is | m. | madness |

| labor, labōr-is | m. | struggle; effort |

| timor, timōr-is | m. | fear |

| cōnsul, cōnsul-is | m. | consul (the two highest elected officials at Rome) |

Genitive Singular Ending of Third Declension Nouns

“There is one more declension (family) of nouns beyond the four we learned yesterday: 3rd declension nouns. In the dictionary they are easy to recognize: the genitive singular of any 3rd declension noun ends in -is. Do you remember the genitive-stem rule? The genitive singular form tells you which declension the noun belongs to, and it also tells you the stem of the noun. Compare the genitive singular forms we’ve learned so far:”

Genitive Singular Endings, Declensions 1-5

| Declension | Ending | Stem + Ending | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st declension | -ae | vi-ae | of road |

| 2nd declension | -ī | amīc-ī | of friend |

| 3rd declension | -is | rēg-is | of king |

| 4th declension | -ūs | man-ūs | of hand |

| 5th declension | -eī | r-eī | of thing |

Accusative Singular Ending of Third Declension Masculine or Feminine Nouns

“3rd declension nouns that are either masculine or feminine – the only ones we will study today – have an accusative singular ending -em. So, today you only need to memorize two new endings, genitive singular -is and accusative singular -em, for 3rd declension nouns that are either masculine or feminine. Compare the accusative singular forms we’ve learned so far:”

Accusative Singular Endings, Declensions 1-5

| Declension | Ending | Stem + Ending | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st declension | -am | vi-am | road (object) |

| 2nd declension | -um | amīc-um | friend (object) |

| 3rd declension | -em | rēg-em | king (object) |

| 4th declension | -um | man-um | hand (object) |

| 5th declension | -em | r-em | thing (object) |

“As for the nominative singular form, there is no consistent nominative singular ending for every 3rd declension noun. You must memorize the nominative singular form of any 3rd declension noun! To recap: for any noun, the stem is the genitive singular form minus the genitive singular ending; for 3rd declension nouns you must also learn the nominative singular form. So, given the 3rd declension noun urbs, urb-is, the nominative singular is urbs and the stem is urb-.”

Drill: Genitive and Accusative Singular Forms

“Provide the genitive singular and accusative singular forms of the following 3rd declension noun based on the example; remember to follow the genitive-stem rule to identify the stem:”

| Nominative Singular | Genitive Singular | Accusative Singular |

|---|---|---|

| urbs | urb-is | urb-em |

| lēx | ||

| mōs | ||

| timor | ||

| mors | ||

| lībertās |

Exercises 1-11

“Today, in your notebook, attempt the assigned translation exercises using the step-by-step method (steps I-III) introduced in Explōrātiō IV (Ex. IV: Translating Sentences).”

1. Mors rēgem manēbit.

2. Lēgem populus timēbat.

3. Fīlia rēgis nōs docet.

4. Vōx cōnsulis vōs movēbit.

5. Mūtāte mōrem patriae! Rēs pūblica nōn valet.

6. Lībertātem et fidem servāre spērāmus.

7. Timor et spēs nihil mūtābunt, sī dea sīc cōgitābit.

8. I fear the madness of the king.

9. Do you fear the voice of the people?

10. The consul will preserve the freedom of the country.

11. If you all fear death, you all have a life of struggle.

Prepositional Phrases

“The accusative case has another function besides marking the object of a verb: a word in the accusative case can be the object of a preposition. Together, the accusative word and preposition form a prepositional phrase. A preposition is a little word that has a noun or pronoun as its object – ‘in’, ‘to’, ‘for’, ‘by’ are all examples of English prepositions. A prepositional phrase is a preposition combined with a noun or pronoun. Three common Latin prepositions that go with or ‘govern’ an accusative word are ad, in, and per. Notice the accusative ending on each noun in the examples below.”

Vocabulary: Prepositions

| Latin Preposition + Case | English Meaning | Latin Example | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ad + accusative | to; towards | ad urbem | to the city; towards the city |

| in + acc. | into (a place); against (someone/thing); for (a purpose) | in patriam | into the country; against the country |

| per + acc. | through | per furōrem | through madness |

Translating a Sentence with a Preposition

“When you mark up a sentence, underline the preposition and the noun or pronoun that it goes with.”

Translating a Sentence with a Preposition: Examples

I. Vōx mē ad tē vocat.

II. Vōx (nom. sg. fem..) mē (acc. sg.) ad tē vocat (3rd sg. pres.)

III. A voice (nom. subj.) calls (3rd sg. pres.) me (acc. obj.) to you.

I. Through hope we (subj. nom.) will preserve (1st pl. fut.) the country (obj. acc.).

II. per + acc. : spēs, spēī f. : nōs : servō, servāre : patria, patriae, f.

III. Per spem nōs patriam servābimus.

Exercises 12-15

12. Ad furōrem timor rēgem movēbit.

13. Is inimīcum per urbem, ad senātum movēbat.

14. The enemy plans death against the consul.

15. Through the law of the people the consul will preserve freedom.

Initial sum

“Another tip: when the first word in a sentence is a 3rd person form of sum, esse, such as est or sunt, and the sentence includes a nominative noun, then the verb should usually be translated ‘there is’ (if singular) or ‘there are’ (if plural); ‘it is’ sometimes works, too. Similarly, translate initial erat ‘there was’,erant ‘there were’ (imperfect), and initial erit or erint ‘there will be’ (future).”

Initial sum Examples

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Est amīcus. | There is a friend. |

| Sunt geminī. | There are twins. |

| Erat mōs populum vocāre. | It was the custom to call the people. |

Exercises 16-18

16. Est lēx senātūs.

17. Erant fīlius et fīlia. Geminī erant.

18. It was the custom to preserve something of hope.

Conjunctions

Vocabulary: Conjunctions

| Latin Conjunction | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| atque / ac | and |

| -que | and |

Asyndeton

“Latin has a fondness for lists. Some lists are made of similar kinds of words – nouns in the same case, verbs of the same form – without the conjunction et. This is called asyndeton, a term which means ‘no conjunctions’.”

Asyndeton Example

Familiam, rem pūblicam, patriam servābimus.

We will preserve the family, the republic, the country.

Polysyndeton

“Latin also makes lists of similar kinds of words linked by a repeated et or atque. This repetition is called polysyndeton, ‘many conjunctions’. Polysyndeton can also occur with a repeated nec, ‘neither… nor… nor… nor…’”

Polysyndeton Example

Nec familiam, nec rem pūblicam, nec patriam cōnsul servābit.

The consul will preserve neither the family, nor the republic, nor the country.

The Conjugation -que

“Finally, Latin has another way to say ‘and’ besides et: by adding the ending -que to the word to be joined. So, instead of saying ‘X et Y’, you can say ‘X Yque’. To translate a sentence with -que, you should mentally break off the -que and put it before the word it was attached to; then translate -que like et.”

Translating –que Examples

| 1. Latin | 2. Break off -que | 3. Mentally put before word | 4. Translate like 'et' |

|---|---|---|---|

| ego tūque | ego tū-que | ego -que tū | I and you |

| mē eumque | mē eum-que | mē -que eum | me and him |

Exercises 19-25

19. Rēx nōs parāre, cōgitāre, spērāre, valēre iubēbit.

20. Nec vīta nec patria nec urbs neque familia tē movēbit, ō Catilīna.

21. Vōs mēque cōnsul per lēgem servābit.

22. Senātus populusque tē manēre iubent.

23. Custom and fear teach me to prepare well.

24. Neither hope, nor trust, nor custom moves the enemy.

25. Do you plan death against me, against the city, against the Republic?

“That will do for now,” she said as we stood up. The torches of the night-watch were still burning in the temple. “Cicero, with his speech, has just barely managed to head off a bloody revolution. He has smoked out the rebel leaders and will force them to leave the city. Catiline has an army waiting for him out in the countryside, which will be defeated by a Roman legion sent against it by Cicero. Catiline’s corpse will be found among those who fought and died in the front line; he is a brave man, whatever his other faults.”

“Cicero will boast about this victory to no end, but his elation will not last long. The next man to combine populist sympathies with aristocratic charisma will have another tool at his disposal: a massive, battle-hardened army. We will learn more about him a few days from now, when we visit the soldiers of Julius Caesar.”

Just as she said this, Catiline stalked out of the temple of Jupiter and immersed himself in a group of armed men. It felt like a relief to escape from this world of violence and threats, of angry men and furious goddesses, and find myself back home in my comfortable bed.

Yet the next morning, for some strange reason, I wanted desperately to return to Rōma.

11. David Bamber as the ōrātor Cicero in the HBO Miniseries Rome. The togae or togas are accurately reconstructed. Togas were made of lāna, wool.