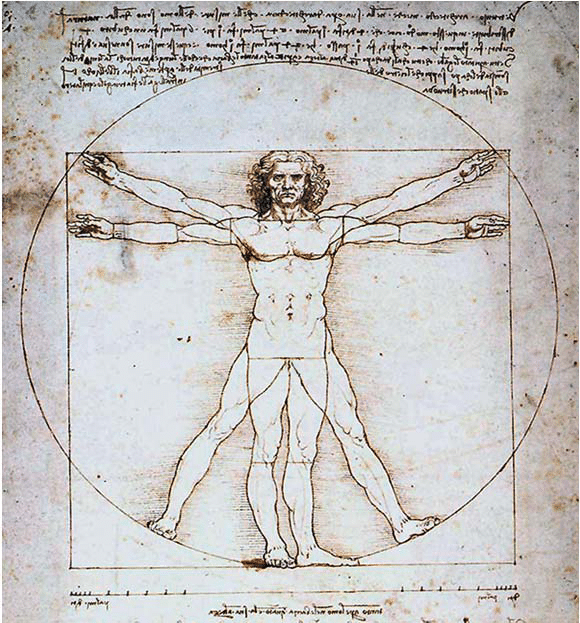

27. Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous illustration of ‘Vitruvian Man’, 1492. This design is based on a description, in Vitruvius’ Dē Architectūrā, 3.1.2, of the proportions of the corpus hominis, the body of a human being.

Explōrātiō Tertia Decima (XIII) Adventure Thirteen

Universal Features of Neuter Nouns

3rd Declension Neuter Case Endings

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension Neuter Nouns

3rd Declension Neuter Noun Case Forms

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension Neuter Nouns, Cont.

Drill: 3rd Declension Neuter Noun Case Forms

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension Neuter Nouns, Cont.

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension I-Stem Neuter Nouns

Fourth Declension Neuter Nouns

Vocabulary: 4th Declension Neuter Noun

Vitruvius, Dē Architectūrā, Excerpt

Where and When Are We Today?

Collis Quirīnālis, Rōma

Mēnsis November

Imp. Caesare L. Volcāciō Tullō cōnsulibus

Quirinal Hill, Rome

November, 33 BCE

The sky loomed grey and foggy the next morning as we ascended a winding dirt road in the city of Rome. Our destination was a cluster of residential compounds located on one of the Seven Hills, the Collis Quirīnālis, or Quirinal Hill, in the north end of the city. Looking back at the street below, I saw it littered with stones and burnt-out torches; one especially ugly spot, where blood had been shed, was busy with flies. An uncomfortable silence hung in the air, and made me eager to get to higher ground, out of sight. I caught up to Latinitas, who was moving briskly and talking in a constant stream:

“Ever since the death of Brutus and Cassius, Caesar’s assassins – who committed suicide six years ago after being defeated in battle by Marc Antony and Octavian – there has been peace in Rome, but little justice. The triumvirs Octavian and Antony pushed out Lepidus and divided up the empire among them. Octavian now commands the western portion of the Empire, including Rome, while Antony has set himself up as the emperor of the east. Each man has his loyalists, but neither commands a loyal majority of the armies or people of Rome. There have been food shortages in the city – the riots last night started as protests over the high cost of grain – and it’s not at all clear right now who will emerge the winner.”

Vitruvius

“This is our destination: the house of Atticus, Cicero’s friend,” Latinitas informed me as we slipped past a guard slumbering at the gate. “Octavian is staying here temporarily to avoid the riots, which tend to start further downtown. He is accompanied by his most capable general, Agrippa, and his sister, Octavia. This morning they are meeting with the usual assortment of individuals who seek audiences with powerful men – suppliants, opportunists, informants, double-agents, and the occasional new and useful ally. The man you see being led into the garden now is a job-seeker named Vitrūvius.”

We slipped into an empty bedroom to watch the interview take place. Vitruvius stepped slowly into the garden and bowed his head forward to acknowledge the trio. In the center sat Octavian, a young man of 30. He was not very imposing physically, but he had a great deal of skepticism and intensity in his eyes, like an old spymaster. Agrippa had a soldier’s bearing and gave the impression of a man who had never laughed once in his entire life. Only Octavia brought some warmth to the scene, seeming mildly bemused.

“You built artillery for my father in Gaul?” Octavian asked Vitruvius.

“Yes, for Julius Caesar, a great man. I built for him catapults, rams, bridges, forts, fortifications, carriages, sundials, and waterpipes, and have also designed a new basilica for the town of Fanum Fortunae, which, however, the present troubles have made it impossible to start work on.”

“Agrippa, do we need a man who can build catapults and the like?”

“Marc Antony spends his days in Alexandria, where the talent for making such things is deep.”

“I see. Now tell me, good man: you have a lazy eye, a clubfoot, and a tremor in your left arm. The Epicureans, like the Stoics, teach that the soul is diffused throughout the body, relies on it, and suffers along with it. If these qualities of the body hinder your motions, do they not also hamper your powers of mind?”

“Very wise are the teachers you name, imperātor, wise indeed. But I will tell you another story. When Alexander the Great was conquering the world, the architect Dinocrates, trusting in his ideas and ingenuity, set out from Macedonia for the army, desiring a royal commission. He carried letters from relatives and friends written to distinguished men of rank that were designed to ease his way; after receiving a generous welcome, he asked that he be taken to Alexander as soon as possible. Although they promised, the men were rather slow, and kept claiming that the moment was not right. So Dinocrates, who thought that he was being toyed with, looked to his own self for help. He was of very ample height, with a pleasant face, handsomeness, and the utmost dignity. Putting his trust in these natural gifts, he left his clothes at the guest-house, rubbed down his body with olive oil, crowned his head with poplar leaves, and covered his left shoulder with a lion skin. Then, taking a club in his right hand, he marched straight into the court of the king as he was announcing verdicts.”

“Like Hercules,” Octavia said, and Vitruvius nodded.

“When this strange sight distracted the people, Alexander took notice of him. His gaze full of wonder, he ordered that space be given to him, to let the man through, and asked who he was. ‘The architect Dinocrates of Macedon,’ he replied; ‘I bring projects and designs worthy of your great reputation. For I have a design to make Mount Athos into a statue of a man: in his left hand I have drawn the walls of a sizeable city, and in his right a shallow bowl, which will receive water from all the streams on the mountain and pour it from there into the sea.’”

“Alexander, who was delighted by the idea of the design, asked at once if there was land nearby which could supply the city with a suitable amount of grain. When he found out that it would be impossible without using shipments from across the sea, he said, “Dinocrates, I appreciate the spectacular composition of your design and find it charming. But I also notice that anyone who established a settlement on that site would find people criticizing his judgment. For just as a new-born infant cannot be nourished or enter its first stage of growth without a nurse’s milk, so a city without land and the fruits of that land cannot grow inside its generous walls; it will have no population without an abundance of food, and without resources it will not preserve its people. Thus, as much I think your design should be approved, I would say that the location cannot be approved. But I want you to be with me, because I will make use of your work.”

“After that Dinocrates did not leave the king’s side and followed him to Egypt. There, when Alexander noticed that there was a naturally safe port and a wonderful trading post, that fields all over Egypt were full of grain and that the advantages of the massive Nile river were huge, he ordered Dinocrates to build a city there with his name – Alexandria.”

“Thus Dinocrates arrived at such fame after being recommended by his face and the dignity of his body. But as for me, imperātor, nature has not afforded me much height, time has deformed my face, and ill-health has diminished my strength. So, because I have been abandoned by such assistants, it is through the aid of my knowledge and writings that, I hope, I will win through to a commission.”

“You seem to be rather more learned than the ordinary craftsman,” Octavia observed.

“I am, o sister of Caesar, that I am; and I have a mind, someday, when the bite of poverty is no longer so sharp, to compose a book about such things and others.”

“To read this book would please me very much. You will write it whenever Jupiter gives you leisure.”

“Go, now, and be well,” Octavian concluded. “If you become one of our friends, the fact will not escape your notice.”

Vitruvius turned and walked away, supporting himself with the help of a servant and a straight walking stick, which, as he passed, we saw was marked with common Roman measures: the cubitum, or cubit, 1 ½ feet long; the pēs, or foot; and the digitus, or finger, equal to 1/16 of a foot. To judge from his age and the look on his face, Vitruvius’ aged assistant had been with him a very long time.

We walked back outside and sat down next to some peacocks as streams of fog tumbled through the trees above us.

“Patronage is one of the institutions that holds Roman society together, just as it does in other communities around the Mediterranean. Every senator, knight, or man of great wealth has a small army of allies who perform various tasks for him. For their efforts they’re rewarded with gifts or grants of money – often very large gifts, delivered after a major service, and not set by any kind of contract. Patrons and clients refer to each other as ‘friends’, but you can tell who has the real power; a client, as a dependent, is always somewhat less free.”

“Ambitious men like Pompey, Caesar, Antony, and Octavian are well aware that the Romans hate the idea of being ruled by a king and pride themselves on their so-called ‘freedom’. The practice of patronage offers them another way to be in charge. Although they have king-like powers in practice, they do so outside of the regular institutions of government, by being the super-patron of the entire Roman people, including the ruling class.”

When she was done with her lecture Latinitas had me practice reading the Latin from a copy of Vitruvius’ Dē Architectūrā that she had brought along. It was a beautifully illustrated modern edition, with diagrams clarifying Vitruvius’ descriptions of the ideal proportions for temples and other buildings. I read it and then we turned to more grammar.

Third Declension Neuter Nouns

“Today we will finish studying the forms of regular nouns by looking at more neuter nouns. Do you remember the universal features of neuter nouns? I mean these:”

Universal Features of Neuter Nouns

The nominative and accusative singular forms are always identical.

The nominative and accusative plural forms are always identical.

The nominative and accusative plural forms always end in -a.

Ok, yes I do.

“The endings of neuter 3rd declension nouns resemble other 3rd declension nouns, except for variants in the nominative and accusative that follow these principles. So:”

3rd Declension Neuter Case Endings

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Nom. | -varies | -a |

| Gen. | -is | -um |

| Dat. | -ī | -ibus |

| Acc. | -same as nom. | -a |

| Abl. | -e | -ibus |

“Like masculine and feminine 3rd declension nouns, there is no consistent nominative singular ending for neuter nouns. One nominative (and accusative) singular ending that you will often see for 3rd declension neuter nouns is -us:”

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension Neuter Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| corpus, corpor-is | n. | body |

| mūnus, mūner-is | n. | gift; service; duty |

| tempus, tempor-is | n. | time |

| iūs, iūr-is | n. | justice |

| sīdus, sīder-is | n. | star |

3rd Declension Neuter Noun Case Forms: corpus, corporis, n.

| Singular | 3rd Decl. Neuter |

|---|---|

| Nom. | corpus |

| Gen. | corpor-is |

| Dat. | corpor-ī |

| Acc. | corpus |

| Abl. | corpor-e |

| Plural | |

| Nom. | corpor-a |

| Gen. | corpor-um |

| Dat. | corpor-ibus |

| Acc. | corpor-a |

| Abl. | corpor-ibus |

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension Neuter Nouns, Cont.

“Some neuter 3rd declension nouns have the nominative and accusative singular ending -men, whereas the stem for the other cases ends in -min-:”

3rd Declension Neuter Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| lūmen, lūmin-is | n. | light; lamp; eye “Lūx is light, whereas lūmen is what makes light.” |

| nōmen, nōmin-is | n. | name |

| flūmen, flūmin-is | n. | river |

3rd Declension Neuter Noun Example: lūmen, lūminis, n.

| Singular | 3rd Decl. Neuter |

|---|---|

| Nom. | lūmen |

| Gen. | lūmin-is |

| Dat. | lūmin-ī |

| Acc. | lūmen |

| Abl. | lūmin-e |

| Plural | |

| Nom. | lūmin-a |

| Gen. | lūmin-um |

| Dat. | lūmin-ibus |

| Acc. | lūmin-a |

| Abl. | lūmin-ibus |

Drill: 3rd Declension Neuter Noun Case Forms

“Provide all the case forms (genitive, dative, accusative, ablative singular; nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, ablative plural) for the following neuter 3rd declension nouns, which are given in the nominative singular form.”

| Singular | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nom. | tempus | nōmen |

| Gen. | ||

| Dat. | ||

| Acc. | ||

| Abl. | ||

| Plural | ||

| Nom. | ||

| Gen. | ||

| Dat. | ||

| Acc. | ||

| Abl. |

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension Neuter Nouns, Cont.

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| caput, capit-is | n. | head; person; animal “The latter meanings are similar in English: ‘count heads’, ‘heads of cattle’.” |

“The word for ‘head’ is caput for the nominative and accusative singular, but capit- is its stem for the other case forms:”

3rd Declension Neuter Noun Example: caput, capitis, n.

| Singular | 3rd Decl. Neuter |

|---|---|

| Nom. | caput |

| Gen. | capit-is |

| Dat. | capit-ī |

| Acc. | caput |

| Abl. | capit-e |

| Plural | |

| Nom. | capit-a |

| Gen. | capit-um |

| Dat. | capit-ibus |

| Acc. | capit-a |

| Abl. | capit-ibus |

Vocabulary: 3rd Declension I-Stem Neuter Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| mare, mar-is | n. | sea |

| moenia, moen-ium | n. | walls (of a city) “This word only exists in the plural.” |

“The Latin word for ‘sea’ is an i-stem 3rd declension neuter noun. Its stem is mar-, like ‘marine’ in English. Because it is an i-stem, it features the letter -i- in some endings: -ī in the ablative singular, -ia in the nominative and accusative plural, and -ium in the genitive plural. Another word following this pattern is moenia, but it only has the plural forms.”

I-Stem 3rd Declension Neuter Noun Example: mare, maris, n.

| Singular | 3rd Decl. Neuter |

|---|---|

| Nom. | mare |

| Gen. | mar-is |

| Dat. | mar-ī |

| Acc. | mare |

| Abl. | mar-ī |

| Plural | |

| Nom. | mar-ia |

| Gen. | mar-ium |

| Dat. | mar-ibus |

| Acc. | mar-ia |

| Abl. | mar-ibus |

“With all neuter nouns, it is important to remember that the accusative and the nominative are the same form. So, when you see these Latin forms, you have to keep in mind that they can be either of the two cases.”

Exercises 1-10

1. Clārum est hoc sīdus.

2. Multī virī interiērunt: sīc ante moenia corpora eōrum iacent.

3. Post hoc bellum mūnus pācis populō tōtī dabitur.

4. Temporibus malīs multa timēmus: arma, amīcōs falsōs, ducēs sine modō.

5. Lūmen superum et haec sīdera rēs hūmānās vident.

6. Nōnne rēgēs bonī iūs vērum servābunt?

7. Flūmina per terrās in mare īvērunt.

8. Nīl est nōmen, glōria, fāma sine capite meō.

9. To whom will you give these gifts?

10. One name seems to be false, but another true.

Fourth Declension Neuter Nouns

“There are not many neuter 4th declension nouns. We’ll start with the noun cornū, ‘horn’.”

Vocabulary: Fourth Declension Neuter Noun

4th Declension Neuter Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| cornū, corn-ūs | n. | horn |

“The endings for neuter 4th declension nouns differ from masculine or feminine 4th declension nouns in 5 places – the nominative, dative, and accusative singular, and the nominative and accusative plural:”

4th Declension Neuter Noun Example: cornū, cornūs, n.

| Singular | 4th Decl. Neuter |

|---|---|

| Nom. | corn-ū |

| Gen. | corn-ūs |

| Dat. | corn-ū |

| Acc. | corn-ū |

| Abl. | corn-ū |

| Plural | |

| Nom. | corn-ua |

| Gen. | corn-uum |

| Dat. | corn-ibus |

| Acc. | corn-ua |

| Abl. | corn-ibus |

“Here are a few more new words that you will see shortly:”

Vocabulary

1st Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| aqua, aqu-ae | f. | water |

| cōpia, cōpi-ae | f. | abundance; plural: forces (e.g. of soldiers) |

2nd Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| ager, agr-ī | m. | field; land (“Land as a piece of property.”) |

2nd Declension Neuter Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| auxilium, auxili-ī | n. | aid; help |

| iūdicium, iūdici-ī | n. | judgment |

5th Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| faciēs, faci-eī | f. | face; appearance |

Conjunctions

| Latin | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| ut | as; when |

| igitur | then; therefore |

| itaque | and so; therefore |

Adverb

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| forte | by chance |

“Now translate these sententiae or sentences:”

Exercises 11-20

11. Sīdera, cum nox est, hominum vident amōrēs.

12. Itaque Dīnocratēs fidem in mūneribus nātūrae habuit.

13. Dīnocratēs litterās ab amīcīs ad virōs ōrdinis magnī habuit.

14. Cōpiae igitur nōn ad auxilium sed forte īvērunt.

15. Huic virō sunt nōmen clārum et faciēs bona; commodus igitur esse vidētur.

16. Aquae flūminis ex hōc capite per agrōs meōs in mare eunt.

17. Good Fortune holds the Horn of Abundance.

18. And so he ordered a state to be prepared.

19. Using (by means of) good judgment and talent he prepared a state.

20. By this (man) the state will be prepared.

Vitruvius, Dē Architectūrā, Excerpt

“Now let us read the Latin of the anecdote Vitruvius told Octavian about Dinocrates. As you read it, identify the meaning and the case form of the nouns and pronouns shown in bold:”

1) Dīnocratēs architectus cōgitātiōnibus et sollertiā frētus, cum Alexander rērum potīrētur, profectus est ē Macedoniā ad exercitum, rēgiae cupidus commendātiōnis. Is ē patriā ā propinquīs et amīcīs tulit ad prīmōs ōrdinēs et purpurātōs litterās, aditūs habēret faciliōrēs, ab eīsque exceptus hūmānē petit utī quamprīmum ad Alexandrum perdūcerētur. Cum pollicitī essent, tardiōrēs fuērunt idōneum tempus expectantēs.

When Alexander the Great was conquering the world, the architect Dinocrates, trusting in his ideas and ingenuity, set out from Macedonia for the army, desiring a royal commission. From his country he carried letters from relatives and friends written to distinguished men of rank that were designed to ease his way; after receiving a generous welcome, he asked that he be taken to Alexander as soon as possible. Although they promised, the men were rather slow, and kept claiming that the moment was not right.

2) Itaque Dīnocratēs ab hīs sē exīstimāns lūdī ab sē petit praesidium. Fuerat enim amplissimā statūrā, faciē grātā, fōrmā dignitāteque summā. Hīs igitur nātūrae mūneribus cōnfīsus vestīmenta posuit in hospitiō et oleō corpus perūnxit caputque corōnāvit pōpuleā fronde, laevum umerum pelle leōnīnā tēxit, dextrāque clāvam tenēns incessit contrā tribūnal rēgis iūs dīcentis.

So Dinocrates, who thought that he was being toyed with by these men, looked to his own self for help. He was of very ample height, with a pleasant face, handsomeness, and the utmost dignity. Putting his trust in these natural gifts, he left his clothes at the guest-house, rubbed down his body with olive oil, crowned his head with poplar leaves, and covered his left shoulder with a lion skin. Then, taking a club in his right hand, he marched straight into the court of the king as he was announcing verdicts.

3) Novitās populum cum āvertisset, cōnspēxit eum Alexander. Admīrāns eī iussit locum darī, ut accēderet, interrogāvitque, quis esset. At ille: “Dīnocratēs“, inquit, “architectus Macedō quī ad tē cōgitātiōnēs et fōrmās adferō dignās tuae clāritātī. Namque Athōn montem fōrmāvī in statuae virīlis figūram, cuius manū laevā dēsignāvī cīvitātis amplissimae moenia, dexterā pateram, quae exciperet omnium flūminum, quae sunt in eō monte, aquam, ut inde in mare profunderētur.”

When this strange sight distracted the people, Alexander took notice of him. His gaze full of wonder, he ordered that space be given to him, to let the man through, and asked who he was. ‘The architect Dinocrates of Macedon,’ he replied; ‘I bring projects and designs worthy of your great reputation. For I have a design to make Mount Athos into a statue of a man: in his left hand I have drawn the walls of a sizeable city, and in his right a shallow bowl, which will receive water from all the streams on the mountain and pour it from there into the sea.’

4) Dēlectātus Alexander nōtiōne fōrmae statim quaesiit, sī essent agrī circā, quī possint frūmentāriā ratiōne eam cīvitātem tuērī. Cum invēnisset nōn posse nisi trānsmarīnīs subvectiōnibus: “Dīnocratēs,” inquit, “adtendō ēgregiam fōrmae conpositiōnem et eā dēlector. Sed animadvertō, sī quī dēdūxerit eō locō colōniam, forte ut iūdicium eius vituperētur.”

Alexander, who was delighted by the idea of the design, asked at once if there were fields nearby which could supply the city with a suitable amount of grain. When he found out that it would be impossible without using shipments from across the sea, he said, “Dinocrates, I appreciate the spectacular composition of your design and find it charming. But I also notice that anyone who established a settlement on that site would find people criticizing his judgment.”

5) “Ut enim nātus īnfāns sine nūtrīcis lacte nōn potest alī neque ad vītae crēscentēs gradūs perdūcī, sīc cīvitās sine agrīs et eōrum frūctibus in moenibus affluentibus nōn potest crēscere nec sine abundantiā cibī frequentiam habēre populumque sine cōpiā tuērī. Itaque quemadmodum fōrmātiōnem putō probandam, sīc iūdiciō locum inprobandum; tēque volō esse mēcum, quod tuā operā sum ūsūrus.”

“For just as a new-born infant cannot be nourished or enter its first stage of growth without a nurse’s milk, so a city without fields and their fruits cannot grow inside its generous walls; it will have no population without an abundance of food, and without resources it will not preserve its people. Thus, as much I think your design should be approved, I would say that the location cannot be approved. But I want you to be with me, because I will make use of your work.”

6) Ex eō Dīnocratēs ab rēge nōn discessit et in Aegyptum est eum persecūtus. Ibi Alexander cum animadvertisset portum nātūrāliter tūtum, emporium ēgregium, campōs circā tōtam Aegyptum frūmentāriōs, inmānis flūminis Nīlī magnās ūtilitātēs, iussit eum suō nōmine cīvitātem Alexandriam cōnstituere.

After that Dinocrates did not leave the king’s side and followed him to Egypt. There, when Alexander noticed that there was a naturally safe port and a wonderful trading post, that fields all over Egypt were full of grain and that the advantages of the massive Nile river were huge, he ordered Dinocrates to build a city there with his name – Alexandria.

7) Ita Dīnocratēs ā faciē dignitāteque corporis commendātus ad eam nōbilitātem pervēnit. Mihi autem, imperātor, statūram nōn tribuit nātūra, faciem dēfōrmāvit aetās, valētūdō dētrāxit vīrēs. Itaque quoniam ab hīs praesidiīs sum dēsertus, per auxilia scientiae scrīptaque, ut spērō, perveniam ad commendātiōnem.

Thus Dinocrates arrived at such fame after being recommended by his face and the dignity of his body. But as for me, imperātor, nature has not afforded me much height, time has deformed my face, and ill-health has diminished my strength. So, because I have been abandoned by such assistants, it is through the aid of my knowledge and writings that, I hope, I will win through to a commission.

I got a few dozen words right and Latinitas nodded in satisfaction.

After we were done, I looked up and saw a bit of blue sky breaking through the clouds. I could hear Agrippa’s voice in the distance giving orders to a work crew; I moved to get a better view and spotted them working on the flood gates of an aqueduct. After a few minutes of noise and shouting, water from the aqueduct began to spill down the road at the foot of the hill, rushing between the raised sidewalks and over the cobblestones. Sparkling in the sun, the water picked up the residue of last night’s violence and other bits of urban trash and sent it all tumbling down the hill, down into the great sewer that ran under the Roman Forum, the Cloāca Maxima, from which it fell into the Tiber river, to be taken on its final journey ad mare, to the sea.

28. The well-preserved remains of a Roman aqueduct in Segovia, Spain. The word aqueduct is made from aquae, the genitive form of aqua, and the noun ductus, ‘leading’; an aqueduct is a ‘leading of water.'