29. A nāvicula or small fishing boat on the flūmen Nīlus, the Nile river, in Asyut, Egypt. Vesper est hoc tempus diēī; this time of day is dusk.

Explōrātiō Quarta Decima (XIV) Adventure Fourteen

I-Verb Present Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

Irregular I-Verb ferō, ferre, tulī Present Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

I-Verb Imperfect Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

I-Verb Future Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

How to Distinguish E-Verb (2nd Conjugation) and I-Verb (3rd Conjugation) Forms

I-Verb Infinitive and Imperative Forms

US-A-UM Adjectives (First and Second Declension Adjectives), Continued

US-A-UM Adjectives (First and Second Declension Adjectives) with -er Masc. Nom. Sg. Form

Interlaced Word Order with Noun-Adjective Pairs

Romans in Egypt: Gaius Cornelius Gallus

Cornelius Gallus, Roman Love Poet

Cornelius Gallus’ Love Poetry: A Fragment

Vergil’s Tenth Eclogue: Excerpt

Where and When Are We Today?

Ptolemāis, Aegyptus

Mēnsis September

Imp. Caesare Dīvī fīliō M. Liciniō Crassō cōnsulibus

Ptolemais, Egypt

September, 30 BCE

Although palm trees were protecting our heads from the sun, it was still blazing hot at the edge of the body of water which I at first mistook for a lake; it was only when Latinitas mentioned its name that I realized it was the Nile river. Behind us stood a pillared temple two storeys tall, covered with art and hieroglyphs that even I could recognize as Egyptian. At a nearby boat launch fishermen were bringing in their catch as traders carefully packed their vessels with sacks of grain and bundles of flax. Three women passed us carrying jars of water on their heads and chatting in a language I didn’t recognize. The palm trees rustled in the breeze, and a small team of ibises, flamingo-like birds, hunted for food in the mud flats. It was a tranquil scene, almost like a vacation. So you can imagine my surprise when a man on roof of the temple began shouting, repeating over and over again a phrase I couldn’t understand in a voice full of alarm, warning the people of the town.

Latinitas directed my attention upwind, to the north. Although they were just black dots on the horizon, a large fleet of vessels was coming our way. The man on the roof was alerting the villagers to their approach. Everyone in sight began working with great urgency to finish their tasks before the black boats arrived.

“We have about twenty-five minutes before the Romans put to shore. You will be fine, don’t worry; so will these people. Today, fortunately, there will be no violence, only threats. But tomorrow, at Thebes, a city south of here, the story will be different.”

I took another look at the boats and turned back at her, unsure. But I saw that spark of divine fire in her eyes and remembered that, wherever I went, I traveled in a little bubble of protection.

They speak Latin in Egypt? I asked.

“No, the Egyptians don’t. The fishermen and the traders and the women carrying water are speaking Coptic, the current version of the old Egyptian language. Some also speak Greek. The Greek ruling class in this town, Ptolemais, mainly speak their own language, like the priest who was giving the alarm. Greek settlers made themselves the rulers of this land 300 years ago after Alexander the Great drove out the Persian rulers. The only Latin you will hear today will come from the mouths of those Roman soldiers.”

“Here, let’s move out of the way so we won’t be noticed.” She led me to a clump of thorn bushes growing in the shade at the base of a stone wall near the temple. As we sat down we stirred up a small lizard, who ran up the wall and looked right at me with wise, old eyes.

“Would you like to take a chameleon home today?” she asked. “They are fond of cockroaches. Might be good for your apartment.”

I told her no thanks, then opened up my book.

I-Verbs (Third Conjugation)

“Today I’m going to introduce you to another family of verbs, the third conjugation. Verbs that belong to the third conjugation can be called I-verbs. Verbs in this family have a present infinitive that ends with -ere. That first -e- is short; contrast the present infinitive ending of E-verbs (2nd conjugation): -ēre, with a long ē. Now, copy these into your notebook, and dīc clārā vōce, say them with your voice aloud.” And I did.

Vocabulary

I-Verbs (3rd Conjugation Verbs)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| cēdō, cēd-ere, cess-ī | to yield “This verb often takes a dative word that specifies the person (or thing) to whom the subject yields.” |

| discēdō, discēd-ere, discess-ī | to depart |

| dīcō, dīc-ere, dīx-ī | to say; call |

| ferō, fer-re, tul-ī | to carry; bring; bear; report “Ut ferunt, ‘as they say’, is a common phrase.” |

| adferō, adfer-re, attul-ī | to bring to |

| petō, pet-ere, petīv-ī / peti-ī | to seek; aim for |

| pōnō, pōn-ere, posu-ī | to put; place; lay (something) down |

| quaerō, quaer-ere, quaesīv-ī / quaesi-ī | to search for; ask |

| relinquō, relinqu-ere, relīqu-ī | to leave behind; abandon |

| vīvō, vīvere, vīx-ī | to live |

I-Verb Present Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

“I-verb (3rd conjugation) endings differ from A-verb (1st) and E-verb (2nd) endings in the present tense.”

I-Verb Present Tense, Active Voice Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -ō | -imus | petō | petimus | I seek | we seek |

| -is | -itis | petis | petitis | you seek | you all seek |

| -it | -unt | petit | petunt | he, she, it seeks | they seek |

I-Verb Present Tense, Passive Voice Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -or | -imur | petor | petimur | I am sought | we are sought |

| -eris/-ere | -iminī | peteris/ere | petiminī | you are sought | you all are sought |

| -itur | -untur | petitur | petuntur | he, she, it is sought | they are sought |

Irregular I-Verb ferō, ferre, tulī Present Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

“The present tense endings of the verb ferō are somewhat irregular: the -i- drops out in the 3rd person singular active and passive voice, the 2nd person singular and plural active voice, and the -e- drops out in the 2nd person singular passive voice:”

Irregular I-Verb ferō, ferre, tulī Present Tense Active Voice Forms

| Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| ferō | ferimus | I carry | we carry |

| fers | fertis | you carry | you all carry |

| fert | ferunt | he, she, it carries | they carry |

Irregular I-Verb ferō, ferre, tulī Present Tense Passive Voice Forms

| Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| feror | ferimur | I am carried | we are carried |

| ferris/ferre | feriminī | you are carried | you all are carried |

| fertur | feruntur | he, she, it is carried | they are carried |

Exercises 1-8

1. Ab urbe magnā discēdis.

2. Amor, sī bene petit, petitur.

3. Vīta bona, ut ferunt, semper quaeritur.

4. Rēgī mīlitēs cēdunt et arma in castrīs relinquunt.

5. Alius multa bona, alius mala dīcit.

6. Haec ad vōs adferimus, sed cui bona vidēbuntur?

7. Catullus seeks love with (using) words and the aid of (his) appearance.

8. When your reason has begun to speak, the walls of Nature depart.

I-Verb Imperfect Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

“I-verb (3rd conjugation) imperfect tense forms are exactly the same as those for E-verbs (2nd conjugation), in both the active and passive voice:”

I-Verb Imperfect Tense, Active Voice Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -ēbam | -ēbāmus | petēbam | petēbāmus | I was seeking | we were seeking |

| -ēbās | -ēbātis | petēbās | petēbātis | you were seeking | you all were seeking |

| -ēbat | -ēbant | petēbat | petēbant | he, she, it was seeking | they were seeking |

I-Verb Imperfect Tense, Passive Voice Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -ēbar | -ēbāmur | petēbar | petēbāmur | I was being sought | we were being sought |

| -ēbāris/ēbāre | -ēbāminī | petēbāris/ēbāre | petēbāminī | you were being sought | you all were being sought |

| -ēbātur | -ēbantur | petēbātur | petēbantur | he, she, it was being sought | they were being sought |

Exercises 9-12

9. Via incommoda nōs ferēbat, sed spem in ducibus pōnēbāmus.

10. Rōmānī Octāviānum ‘patrem patriae’ dīcēbant.

11. Laus maxima magis quam virtūs vēra petēbātur.

12. We were yielding to the evils of war, for thus the fates were carrying us.

I-Verb Future Tense, Active and Passive Voice Forms

“I-verb (3rd Conjugation) future tense forms have no -b-, unlike A-verbs and E-verbs. Instead, the future is formed with endings that look like those used for the E-verb (2nd conjugation) present tense, except that the 1st person singular ending is -am:”

I-Verb Future Tense, Active Voice Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -am | -ēmus | petam | petēmus | I will seek | we will seek |

| -ēs | -ētis | petēs | petētis | you will seek | you all will seek |

| -et | -ent | petet | petent | he, she, it will seek | they will seek |

I-Verb Future Tense, Passive Voice Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -ar | -ēmur | petar | petēmur | I will be sought | we will be sought |

| -ēris/ēre | -ēminī | petēris/ēre | petēminī | you will be sought | you all will be sought |

| -ētur | -entur | petētur | petentur | he, she, it will be sought | they will be sought |

How to Distinguish E-Verb (2nd Conjugation) and I-Verb (3rd Conjugation) Forms

“So what happens when you see -e- plus a personal ending on a verb? You should think like this:”

| docēs: It’s an E-verb (2nd conj.). So -e- is the sign of the present, 2nd singular: ‘you teach’. |

| dīcēs: It’s an I-verb (3rd conj.). So -e- is the sign of the future, 2nd singular: ‘you will say’. |

“And an I-verb with the ending -am or -ar is future tense, active and passive voice, respectively: I will (verb); I will be (verbed).”

Drill

“The following words are a mix of E-verb (2nd conj.) and I-verb (3rd conj.) forms. First check whether the verb is an E-verb or I-verb, then identify the person, number, tense, and voice of the form and translate:”

| Latin Form | Verb Conj. | Person, Number, Tense, Voice | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| movētis | |||

| petēris | |||

| dīcentur | |||

| valet | |||

| iubeō | |||

| ferētis | |||

| dēbent | |||

| docēmur | |||

| relinquet | |||

| pōnam | |||

| vidēs | |||

| timent |

Exercises 13-16

13. Fīnis bellī ā bonīs petētur.

14. Cuius esse dīcēris?

15. Mōrēs virīs et moenia pōnet.

16. If you will ask me, I will speak thus.

I-Verb Infinitive and Imperative Forms

“The present active infinitive of an I-verb (3rd conjugation) ends with -ere, but the present passive infinitive ending is just -ī.”

Present Infinitive Endings Compared: A-Verbs, E-Verbs, I-Verbs

| Verb Conj. | Active Ending | Passive Ending |

|---|---|---|

| A-Verb | -āre | -ārī |

| E-Verb | -ēre | -ērī |

| I-Verb | -ere | -ī |

I-Verb Present Infinite Examples

| Stem + Active Ending | Stem + Passive Ending | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pōnere | pōnī | to place | to be placed |

| ferre | ferrī | to carry | to be carried |

“The regular imperative endings for I-Verbs (3rd Conj.) are -e and -ite. The verbs dīcō and ferō are irregular in the imperative:”

Imperative Endings Compared: A-Verbs, E-Verbs, I-Verbs

| Verb Conj. | Singular Act. | Plural Act. | Singular Pass. | Plural Pass. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Verb | -ā | -āte | -āre | -āminī |

| E-Verb | -ē | -ēte | -ēre | -ēminī |

| I-Verb | -e | -ite | -ere | -iminī |

I-Verb Imperative Forms Example

| Stem + Sg. Act. Ending | Stem + Pl. Act. Ending | Stem + Sg. Pass. Ending | Stem + Pl. Pass. Ending |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pōne | Pōnite | Pōnere | Pōniminī |

| Place! | Place, you all! | Be placed! | Be placed, you all! |

I-Verb Irregular Active Imperative Forms

| Latin Verb | Singular Imperative | Plural Imperative | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dīcō, dīcere, dīxī | Dīc | Dīcite | Say! | Say, you all! |

| ferō, ferre, tulī | Fer | Ferte | Bring! | Bring, you all! |

I-Verb Perfect Tense Forms

“The perfect tense forms of I-verbs consist of the usual perfect tense endings on the perfect stem (3rd principal part) of the verb):”

I-Verb Perfect Tense Forms Example: dīco, dīcere, dīxī

| Person | Perfect Tense Forms Singular | Perfect Tense Forms Plural | English Translation Singular | English Translation Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | dīx-ī | dīx-imus | I said/have said | we said/have said |

| 2nd | dīx-istī | dīx-istis | you said/have said | you all said/have said |

| 3rd | dīx-it | dīx-ēre/-ērunt | he/she/it said/has said | they said/have said |

I-Verb Perfect Tense Infinitive Example: dīcō, dīcere, dīxī

| Perfect Tense Form | English Translation |

|---|---|

| dīx-isse | to have said |

Exercises 17-20

17. Vītam bonam vīxī; nunc fātīs cēdam.

18. Dīc mihi, Sulpicia: relīquistīne animum tuum in hāc urbe?

19. Haec signa et arma in castrīs pōnī dēbent.

20. Seek another land, and bring your nation (clan) with you.

US-A-UM Adjectives (First and Second Declension Adjectives), Continued

“Now I want you to add a few new US-A-UM Adjectives to your vocabulary, which you will hear today and tomorrow:”

Vocabulary

US-A-UM Adjectives

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| dūrus, dūr-a, dūrum | harsh; hard |

| nōtus, nōt-a, nōtum | familiar; known |

| saevus, saev-a, saevum | savage |

| tardus, tard-a, tardum | late; slow |

| tūtus, tūt-a, tūtum | safe |

US-A-UM Adjectives (First and Second Declension Adjectives) with -er Masc. Nom. Sg. Form

“Some US-A-UM adjectives end with -er in the masculine nominative singular instead of -us. These nominative forms are like the 2nd declension nouns puer or ager which also have -er instead of -us in the nominative singular. The other forms are all regular. Remember that the adjective stem is the feminine form minus -a. This is the reason why I teach you to make the stem from the feminine form, not the masculine one; it’s for cases like this, where the masculine has -er.”

Vocabulary

US-A-UM Adjectives

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| miser, miser-a, miserum | miserable |

| noster, nostr-a, nostrum | our |

| vester, vestr-a, vestrum | your (belonging to you all) |

Drill

“Try to put these noun and adjective pairings into the specified case form. Remember that the gender of the noun determines the gender you use for the adjective. And keep in mind that the noun may belong to a different declension than the adjective (for example, urbs is a 3rd declension feminine noun, but the feminine form of the adjective bonus, bon-a, bonum is 1st declension):”

| Adjective | Noun | Noun + Adjective case and number | Noun and Adjective in correct form |

|---|---|---|---|

| vester, vestr-a, vestrum | laus, laudis, f. | accusative singular | |

| miser, miser-a, miserum | corpus, corporis, n. | nominative plural | |

| saevus, saev-a, saevum | tempus, temporis, n. | nominative singular | |

| dūrus, dūr-a, dūrum | vultus, vultūs, m. | ablative singular |

Adjective-Noun Word Order

“You may have noticed something about the order of the adjective-noun pairs in Latin that is different from English. In Latin, the adjective very often follows the noun, unlike in English, which puts the adjective first most of the time. When translating Latin into English, you may have to change the order to put the adjective first: dux magnus becomes ‘a/the great leader’.”

“When you translate from English to Latin, always work with the noun first and determine its case and number before adding the adjective, which will have the same gender, case, and number as the noun.”

“In English an adjective will commonly stand immediately before the noun it modifies. But in Latin, there may be a word in between the two – sometimes several words. You can tell that they go with each other by identifying the gender, case, and number of their forms:”

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Fulsēre (3rd pl. pf.) quondam candidī (nom. m. pl.) tibi (dat.) solēs (nom. m. pl.) | White (nom. m. pl.) suns (nom. m. pl.) once shone (3rd pl. pf.) for you (dat.). |

“Because candidī and solēs are both the same gender, case, and number, they go together. So when you put this into English, the adjective must modify the noun: either ‘white suns once shone for you’, or the adjective can be a predicate with the noun – ‘the suns once shone white for you.’”

“In these sentences a verb, noun, adjective, preposition, or conjunction comes between the nouns and the adjectives that modify them; in English, the noun and adjective should go together:”

Exercises 21-23

21. Nīl magnō sine labōre vīta dat.

22. Amōrem saevum hunc ex animō removēre tuō dēbēs.

23. Iūdicia nostra dūrō ā deō miscēbantur.

Interlaced Word Order with Noun-Adjective Pairs

“Sometimes not one, but two pairs of Latin nouns and adjectives will be split from each other, like so:”

| Nōtus in animam ignis meam it. |

| Nōtus (nom. m. sg.) in animam (acc. f. sg.) ignis (nom. m. sg.) meam (acc. f. sg.) it (3rd sg. pr.) |

| A familiar (nom. m. sg.) fire (nom. m. sg.) goes (3rd sg. pr.) into my soul (acc. f. sg.). |

“Now try these examples:”

Exercises 24-25

24. Multa mīlitum relīquimus bonōrum corpora.

25. Dux bonus tūtam dūrā ex necessitāte viam quaeret.

This seemed a little crazy to me, but I did figure it out.

“Finally, add these three 3rd declension nouns to your vocabulary:”

Vocabulary

3rd Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| cupīdō, cupīdin-is | m. | desire; Cupid |

| pēs, ped-is | m. | foot |

3rd Declension I-Stem Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| auris, aur-is | f. | ear |

Exercises 26-27

26. Neither the hands nor the feet of Cupid are slow.

27. He began to speak into our ears about your achievements. “To ‘speak into the ears’ is to whisper or tell a secret.”

Romans in Egypt: Gaius Cornelius Gallus

As the Roman ships got closer, a group of about fifty young Egyptians armed with helmets, bows, and quivers were deliberating in front of us; half of the group positioned themselves to the right of the boat launch, while the others hid behind a line of shrubs to the left. Most of them were teenage boys, no older than sixteen. With their arrows they could bring down an ibis at one-hundred feet – but what chance did they have against a Roman legion?

The fleet then began to put in. Over a hundred boats of varying shapes and sizes pulled up in the shallows, their crews of soldiers splashing out and forming up in units on the shore. I could make out the number XXII on their signa: this was Legiō XXII, the 22nd Legion. In their distinctive red cloth and bronze armor, they made an impressive sight. Once they were ashore, some of the units began to march out of view.

A boat that looked like an old luxury yacht then landed right in front of us. Disembarking was a handsome man – he had Hollywood looks – surrounded by aids and assistants. This was clearly the dux or general of this legion, and Latinitas identified him as Gallus, the poet Gāius Cornēlius Gallus. He was soon joined by a woman riding in a fancy litter with mosquito nets; she poked her face out to look around.

Who is that? I asked. She looks familiar.

“That is the actress Cytheris, who used to be Marc Antony’s mistress. You saw her at the mime show. Now she has a new lover, Gallus here.”

The general pointed to the temple, which was surrounded by legionaries, and climbed some ladders up to the top. A large crowd of Egyptians had gathered in the streets below, wary, nervous, curious. A trumpet sounded, and Gallus addressed them, making a speech in Greek which Latinitas interpreted for me.

The gist of his speech was that he had come to bring what he called ‘good news’: the evil witch Cleopatra was no longer queen of Egypt. One of the poisonous snakes that she kept as pets had bitten her and she had died. He had come to restore the traditional laws and customs of the Egyptians, in the name of the new ruler of Egypt, Caesar Octavianus, who had triumphed over the army led by Cleopatra’s Roman slave-boy, Marc Antony, who was now dead.

As soon as he finished speaking, a group of older women who stood right below him made an uncanny sound, wailing and moaning and ululating. One of the women, dressed all in black, stepped forward to address Gallus. Where are our sons? she demanded to know. Over a year ago all of the young men of fighting age had been marched out of the village and sent off to fight in the far-away land of Hellas. Some had written letters indicating their whereabouts, but so far none had returned. Where are the young men? Where are our sons, our brothers, our nephews, the strength of our city?

The truth, as I learned shortly afterward from Latinitas, was that they had been conscripted into the navy and led into battle by Marc Antony and Cleopatra, who was the last pharaoh of Egypt. They took part in a massive naval battle and were defeated by Octavian and Agrippa at a place called Actium in western Greece. Some of the Egyptians were killed in battle or drowned in storms at sea. Some were taken captive, to be marched in Octavian’s triumphal procession in Rome. Some were sold into slavery. And some, who had switched sides at the right time, were being assimilated into the regular Roman army.

Gallus did not take the occasion to explain all of this to them. Instead, he raised his right hand. The instant he did so, the trumpet blew again, and from every direction massed formations of Roman soldiers suddenly stepped forward, their hands on their swords.

A silence fell over the village which lasted for what seemed like an eternity. Then a small group of old men – elders of the city, too old to believe in any value greater than survival – walked forward and began to yell ‘Khaire Kaisar!’, ‘Hail, Caesar!’ in Greek. This cry was soon taken up by the crowd, with pretend enthusiasm. The women in mourning beat their breasts, but eventually were led away by their families. There was simply no alternative. Even the young men with the bows came out of hiding to add their voices to the chant.

I was upset by what I had seen, but Latinitas patted my hand and told me to be grateful no blood was shed. At my side the chameleon we had scared up earlier was still staring at me with his narrow, wise eyes. I watched him stride away into the tangled shadows of the bush and marveled as he turned from yellow to green, changing color to blend in with the new background. “You don’t see too many dead chameleons,” Latinitas observed.

As the Romans prepared to strike camp, Latinitas walked me over to a pile of Gallus’ baggage, which was unattended. She reached into a red leather case and pulled out a papyrus scroll.

Cornelius Gallus, Roman Love Poet

“Most of the Roman poets you’ve encountered on our past few trips were men from wealthy families who avoided serving in the army or at least tried to. Gallus is different; he’s a career army officer. As it happens, he is also a famous love poet – the best known one since Catullus. This here is his first book of poems,” she said, holding the papyrus in my face.

“Gallus’ book did not survive the fall of pagan Rome. No person from your day has ever seen these poems. So you now have the rare privilege of seeing them – of inspecting the author’s own copy, as a matter of fact.” As she began to unroll it, she added: “The only catch is: you are not allowed to remember what you see. That is the deal I had to make with Clio, the Muse and Goddess of History – no time-travelers are allowed to copy down or remember any texts they see, if those texts did not survive. You only retain a memory of parts that did survive.”

And in fact that’s just what happened: I didn’t remember what I saw – except, that is, for a few lines at the very end of the scroll. The reason is that a few decades ago archaeologists uncovered a fragment of Gallus’ book. It was owned by one of his soldiers, who were camped on an island in the Nile a few days’ sail south of here, and that’s where the archaeologists found it. These were the lines I saw and recalled:

Cornelius Gallus’ Love Poetry: A Fragment

Fāta mihi, Caesar, tum erunt mea dulcia, quom tū

maxima Rōmānae pars eris historiae.

dulcia (ntr. pl. nom./acc. adj.) sweet quom (= cum) historia, histori-ae, f. history

That’s not love poetry, I said after I read it.

“You’re right, it’s not. It is a tribute to Julius Caesar written while the dictator was still alive.”

So what if I wanted to give someone a taste of Gallus’ love poetry? I asked. (I had already gotten it in my head that I would write this textbook.) How can I do that?

“Well, Gallus appears as a character in a poem written by the Roman poet Vergil, his Tenth Bucolic or Eclogue. Scholars think – correctly – that these are imitations and reworkings of lines written by Gallus himself. So if you want to get a better idea of his poetry, you should look at this. Cytheris appears here as Lycoris – that’s Gallus’ nickname for her. At the time Cytheris was off with another soldier-lover:”

And Latinitas recited the following lines for me.

Vergil’s Tenth Eclogue: Excerpt

Try to complete the English translation for the Latin words in bold:

1) Hīc gelidī fontēs, hīc mollia prāta, Lycōrī,

hīc nemus; hīc ipsō tēcum cōnsūmerer aevō.

“Here are cool springs, here, soft meadows, Lycoris,

here, a grove; here may I ____________ be consumed by time itself.

2) Nunc īnsānus amor dūrī mē Mārtis in armīs

tēla inter media atque adversōs dētinet hostīs.

____________ insane ____________ of ____________ Mars detains me in ____________

in the midst of spears and adverse ____________.

3) Tū procul ā patriā (nec sit mihi crēdere tantum)

Alpīnās, ā, dūra, nivēs et frīgora Rhēnī

You, far from your ____________ (would that I did not have to believe something this big)

ah, ____________ woman, you see the snows of the Alps and the frosts of the Rhine river,

4) mē sine sōla vidēs. Ā, tē nē frīgora laedant!

Ā, tibi nē tenerās glaciēs secet aspera plantās!

you ____________, without me. Ah, may the frosts not harm you!

Ah, may the sharp ice not cut your tender feet!”

From the Alps to Egypt, I said. Lycoris has been places.

“She’s very persuasive, yes.”

“But let me tell you about another powerful woman: Amanirenas, the queen of Nubia...”

As we walked through the marketplace of Ptolemais, Latinitas went on to describe how Amanirenas and her army stopped Gallus and kept the Romans from expanding their empire further south along the Nile. It was a fascinating story – but you will need someone who has traveled to ancient Nubia and learned more about the kingdom there to tell it to you.

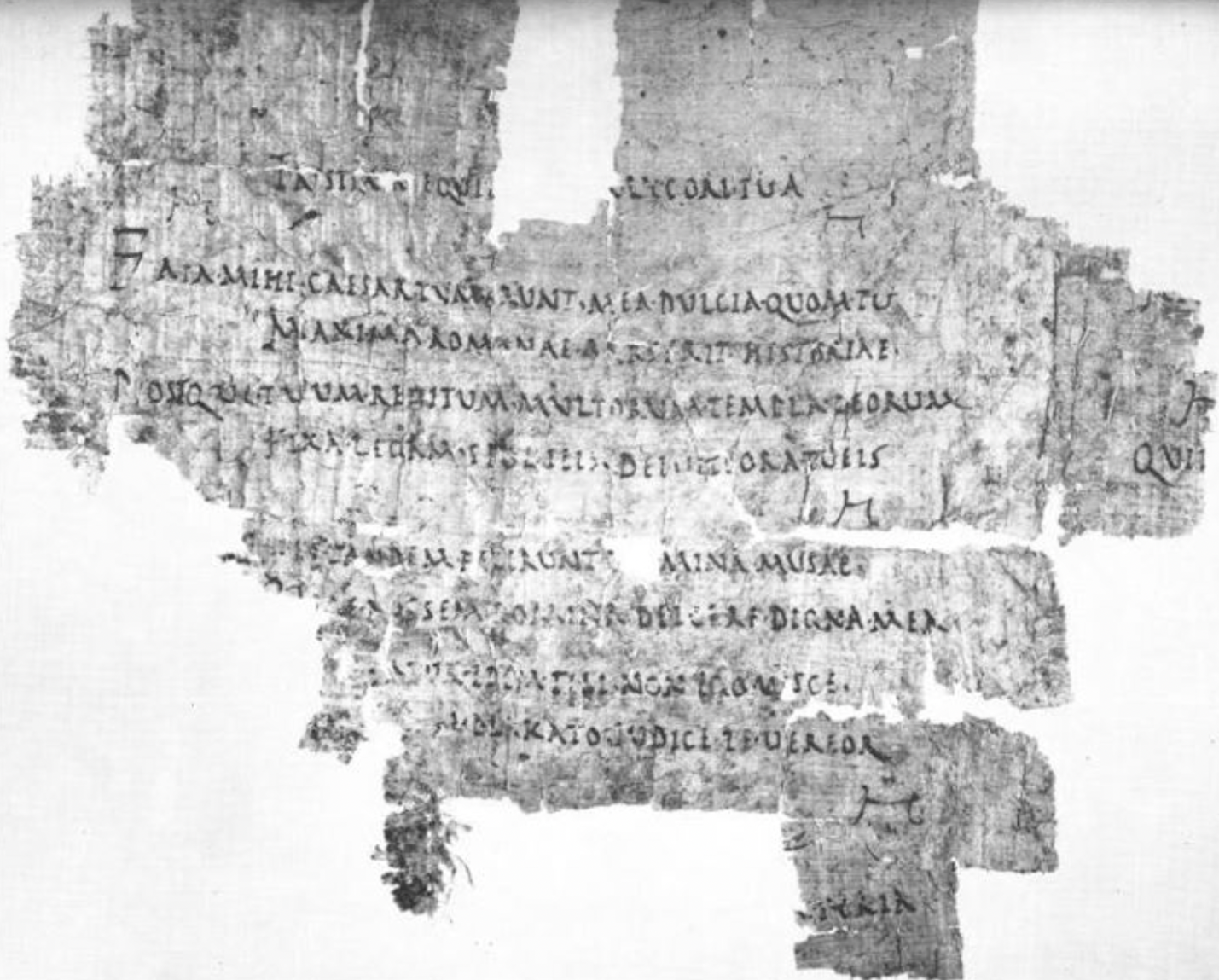

30. A photograph of the fragment of the liber from Egypt containing Gallus’ poetry. Notice how words are separated from each other by pūncta, dots; Roman scribes discontinued this helpful practice around the 3rd century CE, and from then on wrote words without divisions, as scrīptiō continua, continuous script.

31. The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus, by Carle Vernet, 1789. Paulus celebrated this triumph after defeating King Perseus of Macedon in 168 BCE. Paulus is riding in a currus, a chariot, pulled by equī candidī, bright white horses. The temple on the hill in the background is supposed to represent the Aedēs Iovis Optimī Maximī, the Temple of Jupiter the Best and Greatest. The name Jupiter is a 3rd declension noun: Iūppiter, Iov-is, Iov-ī, Iov-em, Iov-e.