69 Adjective-Noun Word Order

“You may have noticed something about the order of the adjective-noun pairs in Latin that is different from English. In Latin, the adjective very often follows the noun, unlike in English, which puts the adjective first most of the time. When translating Latin into English, you may have to change the order to put the adjective first: dux magnus becomes ‘a/the great leader’.”

“When you translate from English to Latin, always work with the noun first and determine its case and number before adding the adjective, which will have the same gender, case, and number as the noun.”

In our ears the great fame of your achievements was being confused. (13)

“In English an adjective will commonly stand immediately before the noun it modifies. But in Latin, there may be a word in between the two – sometimes several words. You can tell that they go with each other by identifying the gender, case, and number of their forms:”

Masc. Nom. Pl.Masc. Nom. Pl.

Fulsērequondamcandidītibisolēs

They shoneoncewhitefor youthe suns

“Because candidī and solēs are both the same gender, case, and number, they go together. When you put this into English, the two words could go right together – ‘white suns once shone for you’ – or the adjective ‘white’ can be a predicate – ‘the suns once shone white for you.’”

“In these sentences a verb, noun, adjective, or conjunction comes between the nouns and the adjectives that modify them; in English, the noun and adjective should go together:”

Ūna pars hominis est mēns locōque manet ūnō. (14)

Nīl sine magnō vīta labōre dat. (15)

Eum amōrem ex animō removēre tuō dēbēs. (16)

“Sometimes not one, but two pairs of Latin nouns and adjectives will be split from each other, like so:”

Nōtum in animā sentiō meā ignem.

Masc. Acc. Sg.Fem. Abl. Sg.Fem. Abl. Sg.Masc. Acc. Sg. Nōtumin animāsentiomeāignem.

“What word does nōtum modify?”

Ignem. “And meā?” Animā.

“Good. So translate: I feel a familiar fire in my soul. Now try this example:” Multa bonōrum invenīmus corpora mīlitum. (17)

This seemed a little crazy to me, but I did figure it out.

“Next try to go from English to Latin. Write this as: Miserable : with bad : I am : boy : with foot. But make sure ‘miserable’ has the same case, gender, and number as ‘boy’, and that ‘bad’ matches ‘foot’”:

I am a miserable boy with a bad foot. (18)

I got it. But at that point I could no longer pay attention to our sentences.

As the Roman ships got closer, a group of about fifty young Egyptians armed with helmets, bows, and quivers were deliberating in front of us; half of the group positioned themselves to the right of the boat launch, while the others hid behind a line of shrubs to the left. Most of them were teenage boys, no older than sixteen. With their arrows they could bring down an ibis at one-hundred feet – but what chance did they have against a Roman legion?

The fleet then began to put in. Over a hundred boats of varying shapes and sizes pulled up in the shallows, their crews of soldiers splashing out and forming up in units on the shore. I could make out the number XXII on their sīgna, or flags: this was Legiō XXII, the 22nd Legion. In their distinctive red cloth and bronze armor, they made an impressive sight. Once they were ashore, some of the units began to march out of view.

A boat that looked like an old luxury yacht then landed right in front of us. Disembarking was a handsome man – he had Hollywood looks – surrounded by aids and assistants. This was clearly the dux or general of this legion, and Latinitas identified him as Gallus, the poet Cornelius Gallus. He was soon joined by a woman riding in a fancy litter with mosquito nets; she poked her face out to look around.

Who is that? I asked. She looks familiar.

“That is the actress Cytheris, who used to be Marc Antony’s mistress. You saw here at the mime show. Now she has a new lover, Gallus here.”

The general pointed to the temple, which was surrounded by legionaries, and climbed some ladders up to the top. A large crowd of Egyptians had gathered in the streets below, wary, nervous, curious. A trumpet sounded, and Gallus addressed them, making a speech in Greek which Latinitas interpreted for me.

The gist of his speech was that he had come to bring what he called ‘good news’: the evil witch Cleopatra was no longer queen of Egypt. One of the poisonous snakes that she kept as pets had bitten her and she had died. He had come to restore the traditional laws and customs of the Egyptians, in the name of the new ruler of Egypt, Caesar Octavianus, who had triumphed over the army led by Cleopatra’s Roman slave-boy, Marc Antony, who was now dead.

As soon as he finished speaking, a group of older women who stood right below him made an uncanny sound, wailing and moaning and ululating. One of the women, dressed all in black, stepped forward to address Gallus. Where are our sons? she demanded to know. Over a year ago all of the young men of fighting age had been marched out of the village and sent off to fight in the far-away land of Hellas. Some had written letters indicating their whereabouts, but so far none had returned. Where are the young men? Where are our sons, our brothers, our nephews, the strength of our city?

The truth, as I learned shortly afterward from Latinitas, was that they had been conscripted into the navy and led into battle by Marc Antony and Cleopatra, who was the last pharaoh of Egypt. They took part in a massive naval battle and were defeated by Octavian and Agrippa at a place called Actium in western Greece. Some of the Egyptians were killed in battle or drowned in storms at sea. Some were taken captive, to be marched in Octavian’s triumphal procession in Rome. Some were sold into slavery. And some, who had switched sides at the right time, were being assimilated into the regular Roman army.

Gallus did not take the occasion to explain all of this to them. Instead, he raised his right hand. The instant he did so, the trumpet blew again, and from every direction massed formations of Roman soldiers suddenly stepped forward, their hands on their swords.

A silence fell over the village which lasted for what seemed like an eternity. Then a small group of old men – elders of the city, too old to believe in any value greater than survival – walked forward and began to yell ‘Khaire Kaisar!’, ‘Hail, Caesar!’ in Greek. This cry was soon taken up by the crowd, with pretend enthusiasm. The women in mourning beat their breasts, but

eventually were led away by their families. There was simply no alternative. Even the young men with the bows came out of hiding to add their voices to the chant.

I was upset by what I had seen, but Latinitas patted my hand and told me to be grateful no blood was shed. At my side the chameleon we had scared up earlier was still staring at me with his narrow, wise eyes. I watched him stride away into the tangled shadows of the bush and marveled as he turned from yellow to green, changing color to blend in with the new background. “You don’t see too many dead chameleons,” Latinitas observed.

As the Romans prepared to strike camp, Latinitas walked me over to a pile of Gallus’ baggage, which was unattended. She reached into a red leather case and pulled out a papyrus scroll.

“Most of the Roman poets you’ve encountered on our past few trips were men from wealthy families who avoided serving in the army or at least tried to. Gallus is different; he’s a career army officer. As it happens, he is also a famous love poet – the best known one since Catullus. This here is his first book of poems,” she said, holding the papyrus in my face.

“Gallus’ book did not survive the fall of pagan Rome. No person from your day has ever seen these poems. So you now have the rare privilege of seeing them – of inspecting the author’s own copy, as a matter of fact.” As she began to unroll it, she added: “There is only catch is: you are not allowed to remember what you see. That is the deal I had to make with Clio, the Muse and Goddess of History – no time-travelers are allowed to copy down or remember any texts they see, if those texts did not survive. You only retain a memory of parts that did survive.”

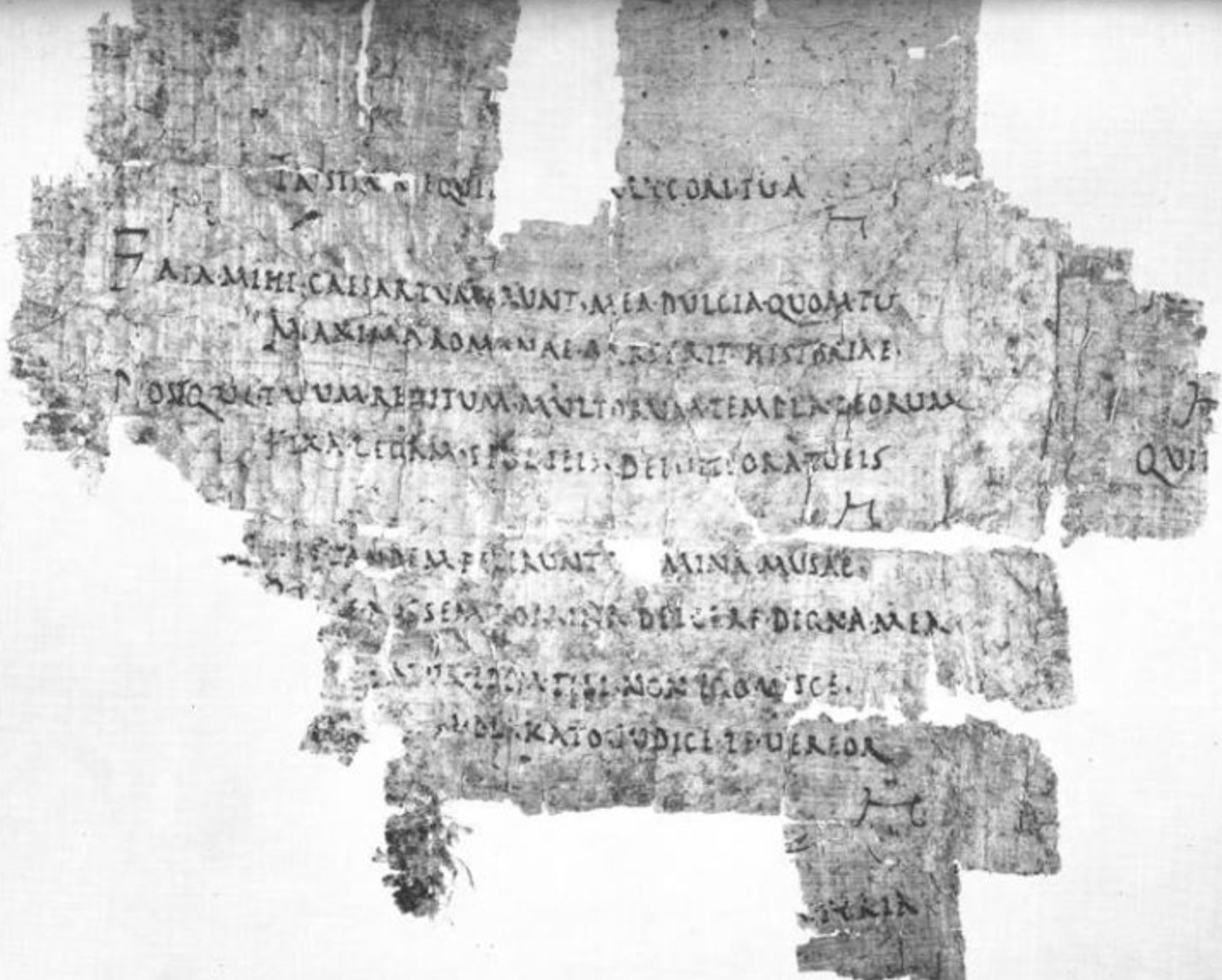

And in fact that’s just what happened: I didn’t remember what I saw – except, that is, for a few lines at the very end of the scroll. The reason is that a few decades ago archaeologists uncovered a fragment of Gallus’ book. It was owned by one of his soldiers, who were camped on an island in the Nile a few days’ sail south of here, and that’s where the archaeologists found it. These were the lines I saw and recalled:

Fāta mihi, Caesar, tum erunt mea dulcia, quom tū

sweet, =cum maxima Rōmānae pars eris historiae.

(19)

That’s not love poetry, I said after I read it.

“You’re right, it’s not. It is a tribute to Julius Caesar written while the dictator was still alive.”

So what if I wanted to give someone a taste of Gallus’ love poetry? I asked. (I had already gotten it in my head that I would write this textbook.) How can I do that?

“Well, Gallus appears as a character in a poem written by the Roman poet Vergil, the Tenth Bucolic. Scholars think – correctly – that these are imitations and reworkings of lines written by Gallus himself. So if you want to get a better idea of his poetry, you should look at this. Cytheris appears here as Lycoris – that’s Gallus’ nickname for her. At the time Cytheris was off with another soldier-lover:”

And Latinitas recited the following lines for me:

Hīc gelidī fontēs, hīc mollia prāta, Lycōrī, hīc nemus; hīc ipsō tēcum cōnsūmerer aevō. Nunc īnsānus amor dūrī mē Mārtis in armīs tēla inter media atque adversōs dētinet hostīs.

Tū procul ā patriā (nec sit mihi crēdere tantum)

Alpīnās, ā, dūra, nivēs et frīgora Rhēnī

mē sine sōla vidēs. Ā, tē nē frīgora laedant!

Ā, tibi nē tenerās glaciēs secet aspera plantās!

“Here are cool springs, here, soft meadows, Lycoris,

here, a grove; here may I be consumed by time itself along with you.

Now insane love of harsh Mars detains me in arms (20)

in the midst of spears and adverse enemies.

You, far from your country (would that I did not have to believe something this big)

ah, hard woman, you see the snows of the Alps and the frosts of the Rhine river alone, without me. Ah, may the frosts not harm you!

Ah, may the sharp ice not cut your tender feet!”

I read the Latin and translated the bit in italics here, and got the gist of the rest. From the Alps to Egypt, I said. Lycoris has been places.

“She’s very persuasive, yes.”

“But let me tell you about another powerful woman: Amanirenas, the queen of Nubia…” As we walked through the marketplace of Ptolemais, Latinitas went on to describe how

Amanirenas and her army stopped Gallus and kept the Romans from expanding their empire

further south along the Nile. It was a fascinating story – but you will need someone who has traveled to ancient Nubia and learned more about the kingdom there to tell it to you.

- A photograph of the fragment of the liber from Egypt containing Gallus’ poetry. Notice how words are separated from each other by pūncta, dots; Roman scribes discontinued this helpful practice around the 3rd century CE, and from then on wrote words without divisions, as scrīptio continua, continuous script.

The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus, by Carle Vernet, 1789. Paulus celebrated this triumph after defeating King Perseus of Macedon in 168 BCE. Paulus is riding in a currus, a chariot, pulled by equī candidī, bright white horses. The temple on the hill in the background is supposed to represent the Aedēs Iovis Optimī Maximī, the Temple of Jupiter the Best and Greatest. The name Jupiter has an odd declension in Latin: Iūpiter, Iovem, Iovis, Iovī, Iove.

The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus, by Carle Vernet, 1789. Paulus celebrated this triumph after defeating King Perseus of Macedon in 168 BCE. Paulus is riding in a currus, a chariot, pulled by equī candidī, bright white horses. The temple on the hill in the background is supposed to represent the Aedēs Iovis Optimī Maximī, the Temple of Jupiter the Best and Greatest. The name Jupiter has an odd declension in Latin: Iūpiter, Iovem, Iovis, Iovī, Iove.

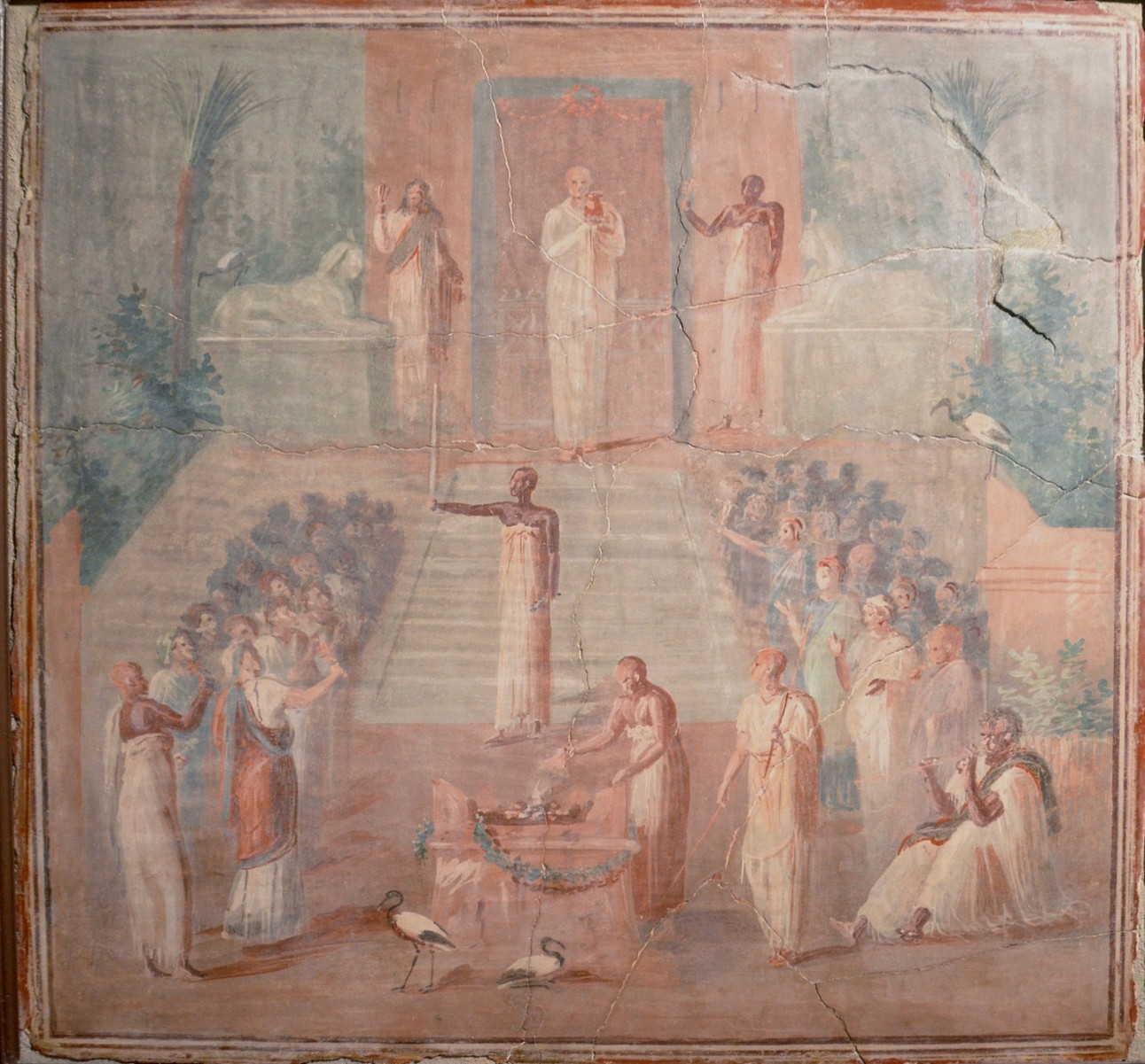

- A fresco from the temple of Isis at Pompeii showing a ceremony in honor of the Egyptian goddess Isis. Isidis sacerdōtēs capita sua radēbant; priests of Isis used to shave their heads.