3. Reconstruction of a vīlla rūstica Rōmāna or a Roman country villa.

Explōrātiō Secunda (II) Adventure Two

Cato the Elder, Dē Agricultūrā Excerpt

Translating from Latin to English

Translating from English to Latin

A-Verbs (First Conjugation): Imperfect and Future Tense

Drill: A-Verbs, Imperfect Tense

Distinguishing Imperfect and Future Tense Forms

Infinitives: Subject and Complement

Supplying ‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’ in English Translation

Where and When Are We Today?

Tusculum, Ītalia

Mēnsis Quīntīlis

L. Aniciō Gallō M. Cornēliō Cēthēgō cōnsulibus

Tusculum, Italy

July, 160 B.C.E.

“Ūnus, duo, trēs, quattuor, quīnque, sex, septem, octō, novem…. Novem adsunt, ūnus abest. Ubi est Porcius? One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine…. Nine are present, one is absent. Where is Porcius?”

The next night, after the ritual of the drink, we were transported to the entrance hall of a vīlla, a grand farmhouse at the foot of a hill in the Italian countryside. Waves of summer heat emanating from the fields outside rolled over us from behind as we stood there. Arranged in the reception room in front of us were three rows of benches on which sat nine middle-aged Roman men, evenly spaced out, each accompanied by one or two slave attendants. An older man with a straight bearing and a very severe look on his face was standing in front of them, scanning the audience. He was evidently waiting for a man named Porcius. Porcius finally arrived – his attendant nudged us out of the way – and took a seat on the back bench, on the end, crossing his arms skeptically.

Catō Māior, Cato the Elder

“The host here is Catō Māior, Cato the Elder,” Latinitas said to me, “a famous conservative Roman statesman. Cato served as a proconsul, or colonial governor, in the Roman provinces of Sardinia and Spain, cracking down hard on corruption among the Roman administration there while also putting down rebellions in ruthless fashion. As with many important Roman politicians, there was a vein of inhumanity running through his character. Carthāgō dēlenda est, Carthage must be destroyed – those are the famous words he ended every speech to the Senate with; and Carthage, Rome’s great rival, a city of hundreds of thousands of people, was indeed destroyed, shortly after Cato’s death. Yet, he also stood up for humanity at times, defending the people on the Greek island of Rhodes after they had supported Greek resistance to Roman rule; he spared them from massacre and enslavement. He was a cruel, talented, occasionally principled, often complicated man.”

“We are visiting him today because of a book he wrote, the first book of Latin prose, entitled dē Agricultūrā, About Agriculture. These men you see here have come for its first public reading. Cato made himself wealthy through farming, and they all hope he will reveal some of the secrets of his success. All of them, that is, except Porcius; Porcius is only here because he is Cato’s cousin and lives in a vīlla about a mile from here.”

With all present and accounted for, the reading started. The beginning of Cato’s advice was as follows:

Cato the Elder, Dē Agricultūrā Excerpt

- Praedium cum parāre cōgitābis, sīc in animō habētō: ut nē cupidē emās nēve operā tuā parcās vīsere et nē satis habeās semel circumīre; quotiēns ībis, totiēns magis placēbit quod bonum erit. Vīcīnī quō pactō niteant, id animum advertitō: in bonā regiōne bene nitēre oportēbit. Et ut eō introeās et circumspiciās, ut inde exīre possīs. Ut bonum caelum habeat; nē calamitōsum sit; solō bonō, suā virtūte valeat. Sī poteris, sub rādīce montis sit, in merīdiem spectet, locō salūbrī; operāriōrum cōpia sit, bonumque aquārium, oppidum validum prope sit; aut mare aut amnis, quā nāvēs ambulant, aut via bona celerisque.

“A farm: when you are planning to acquire one, have in mind the following. Don’t buy greedily, don’t spare any effort to tour it, and don’t consider it enough to go around it just once; the more times you visit, the more a good farm will please you. Pay attention to how the neighbors look: in a good area, they ought to look neat. Also, go into it and be cautious, so that you can back out of the deal. It should have good weather, not be prone to disaster, be endowed with good soil, and be strong by its own merit. If you can, let it be at the foot of a mountain, facing south, in a healthy location. There should be a supply of workmen, and a good water supply, and a thriving town nearby. There should be sea or a river where boats travel, or a road in good shape, and fast.”

2) Sit in hīs agrīs quī nōn saepe dominum mūtant: quī in hīs agrīs praedia vēndiderint, eōs pigeat vendidisse. Ut bene aedificātum sit. Cavētō aliēnam disciplīnam temerē contemnās: dē dominō bonō bonōque aedificātōre melius emētur… Scītō idem agrum quod hominem, quamvīs quaestuōsus sit, sī sumptuōsus erit, relinquī nōn multum. Praedium quod prīmum sit, sī mē rogābis, sīc dīcam: dē omnibus agrīs optimōque locō iūgera agrī centum, vīnea est prīma, vel sī vīnō multō est; secundō locō hortus irriguus; tertiō salictum; quārtō olētum; quīnto prātum; sextō campus frūmentārius; septimō silva caedua; octāvō arbustum; nōnō glandāria silva.

“It should be among pieces of land that don’t change owners often; the people who sell farms among such properties should regret selling them. It should be well built up. Don’t look down on another man’s routines without reason: better to purchase from a good owner and a good builder… Know that a piece of land is just like a person: even if it generates income, if it has many expenses, there won’t be much left over. If you ask me what kind of farm is first, I would say: a hundred acres with all kinds of land, in a prime location. A vineyard is first, or a place with many vines; in second place, an irrigated vegetable farm; in third place a willow grove; in fourth place an olive grove; in fifth, a hay meadow; in sixth, a field of grain; in seventh, a forest for cutting wood; in eighth, an orchard; in ninth, a forest with acorns.”

Once the final sentence was read Porcius suddenly stood up. He made clear through his gestures that he thought Cato was crazy; he went on to argue, Latinitas told me, that a forest with oaks and acorns is best, the best land for profit, because you can feed porcōs, pigs, on acorns, and pigs are the most delicious and most profitable farm animal to raise.

While he and the others got into an argument, we slipped outside. As we left, Latinitas surreptitiously grabbed one of the ten gift copies of the book that we found piled in a red leather container by the entrance. Out in the yard we sat at the foot of a statue of Mercury, the god of commerce. She unrolled the scroll to the passage we had just heard Cato read. She made me read the whole passage in Latin, which I did.

Word Order and Inflection

“Let’s look at the first sentence in Cato. I will turn it into English for you, one word at a time:”

| Praedium | cum | parāre | cōgitābis, | sīc | in | animō | habētō. |

| Farm | when | to acquire | you will plan, | thus | in | mind | have. |

“You will notice that a single Latin word may be translated by more than one English word, like parāre, ‘to acquire’. This is a very common occurrence.”

“Also notice the word order – it is not like English at all! And it does not make much sense translated in order. This is because English (and many other modern languages) conveys meaning through word order: compare ‘The dog bites the mailman’ and ‘The mailman bites the dog’. Latin, however, conveys meaning through Inflection, the different endings or ‘forms’ that a word takes. We will learn these different endings, their meanings, and how to translate them in the coming weeks. When translating, we must always keep in mind that the English and Latin word order of a sentence will often be different.

Here are some common words that are straightforward, since they do not change their forms. You should enter these into your book:”

Vocabulary: Common words

| Latin | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| bene | well (as in ‘I feel well’, not a water source) “This always comes before a verb in Latin, not after it.” |

| sī | if |

| nisi | unless; except |

| sīc | thus; so |

| cum | when |

“But for most words – like praedium, parāre, cōgitābis, animō, habētō – you also need to recognize their specific forms, since these tell you their function and meaning in the sentence. The forms are what help you determine the order in which you translate the Latin into English. We’ll return to this point soon.”

A-Verbs (First Conjugation)

“Today you are going to learn how to use some common verbs besides sum. Write these in your book. Leave a big space between the Latin and the English – enough space to fit two more words – so we can fill it in later. Always write the long marks, because they are part of the spelling of each word:”

Vocabulary: A-Verbs

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| amō, am-āre | I love, to love |

| cōgitō, cōgit-āre | I think, to think; I plan, to plan |

| dō, d-are | I give, to give |

| mūtō, mūt-āre | I change, to change |

| parō, par-āre | I prepare, to prepare; I acquire, to acquire |

| rogō, rog-āre | I ask, to ask |

| servō, serv-āre | I save, to save; I preserve, to preserve “Note: this does not mean ‘to serve’!” |

| spērō, spēr-āre | I hope, to hope |

| vocō, voc-āre | I call, to call |

Principal Parts of the Verb

“The two forms you see for each verb are called principal parts; once you know these, you can make many other forms of the verb–I’ll show you how. The first form is the 1st person, singular, present tense form: amō, I love. The second form is called the infinitive: amāre, to love. An infinitive is a verb form with no personal ending. The infinitive form in English is always ‘to’ plus the verb. Many Latin words have more than one possible English translation, so sometimes you will see more than one English meaning for a new vocabulary word.”

“All of these verbs have an infinitive form that ends with –āre. Verbs like this belong to a family I call A-verbs because they typically contain the letter a. Some people call this verb family the first conjugation. There are other verb families, but today we will focus on this one.”

Verb Stem and Ending

“Just like sum, these verbs have different forms for each person, number, and tense. Each verb form is made up of two parts: a stem, which comes first, and an ending.”

How do you figure out what the stem is? I asked.

“Good question. The stem of an A-verb is the infinitive form without the last three letters, –āre. For example, the stem of amō, amāre is am-.”

“For the verbs you just wrote down, I will show you the stems of the first three, and you tell me the rest:”

| Infinitive | Stem |

|---|---|

| amāre | am- |

| cōgitāre | cōgit- |

| dare | d- |

| mūtāre | |

| parāre | |

| rogāre | |

| servāre | |

| spērāre | |

| vocāre |

A-Verbs: Present Tense

“To these stems you add a set of letters, an ending, which indicates the person, the number, and the tense of the verb. These are the six endings for the present tense of A-verbs; we’ll use cōgitō, cōgitāre as a model:”

A-Verb Present Tense Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Meaning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -ō | -ā-mus | cōgit-ō | cōgit-āmus | I think | we think |

| -ā-s | -ā-tis | cōgit-ās | cōgit-ātis | you think | you all think |

| -a-t | -a-nt | cōgit-at | cōgit-ant | he, she, it thinks | they think |

“Do you see the personal endings that we learned about in Explōrātiō I?”

Yes, there’s ō, and s, t, mus, tis, nt.

“So, except for the first singular, ō, the endings are spelled -ā-, followed by the personal endings. The ā before t and nt loses its long mark.”

Drill: A-Verbs, Present Tense Conjugation

“Conjugate the verb amō, amāre in the present tense. By ‘conjugate’, I mean provide all six forms (1st, 2nd, 3rd person, both singular and plural) of the verb in the present tense. Use the chart above as a guide.”

| Singular | Plural | |

| 1st person | ||

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person |

Irregular dō, dare

“One more thing: the verb dō, dare is slightly irregular. Notice how its infinitive – dare, to give – lacks the long mark. All of its forms except the 2nd person singular – dās, you give – lose the long mark and have short a instead.”

OK. But what happened to the Latin subject pronouns?

Unexpressed Subject Pronouns

“One important feature of Latin is its unexpressed subject pronouns. In English a subject noun or pronoun is spoken or written for every verb. But Latin sentences often let the verb ending alone tell you the subject – the subject pronoun (ego, tū, is, ea, id, etc.) is not expressed. When you translate such a sentence into English, you have to use the correct pronoun.”

Sentences with Unexpressed Subject Pronouns

Parō.

I prepare.

Parātis.

You all prepare.

“If, however, the subject is expressed in the Latin sentence, then you do not need to supply a pronoun in English when translating the Latin verb:”

Sentences with Expressed Noun Subject

Menaechmus parat.

Menaechmus prepares.

Geminī parant.

The twins prepare.

“If the verb is 3rd person singular, you should write ‘he / she / it’, unless you know from the context what gender the subject is.”

Sentences with 3rd Person Singular Verb

Parat.

He / she / it prepares.

Menaechmus amat. Parat.

Menaechmus loves. He prepares.

Today’s RULE: Translating from Latin to English and back again

1. Translating from English to Latin, Illustrated

“The RULE for any Latin sentence today is: I. Read aloud, II. Mark any subject and predicate, plus the person (1st, 2nd, 3rd), number (sg., pl.), and tense (pres., imperf., fut.) of each verb, III. Translate each word, putting them in the appropriate English word order (first the subject, then the verb). Put II. and III. in your notebook, like so:”

| I. Bona est ea. |

| II. Bona (pred.) est (3rd sg. pres.) ea (subj.). |

| III. Good (pred.) is (3rd sg. pres.) she (subj.). >>> She is good. |

| I. Vōs bene parātis. |

| II. Vōs (subj.) bene parātis (2nd pl. pres.). |

| III. You all (subj.) well prepare (2nd pl. pres.). >>> You all prepare well. |

“For translating English into Latin, the RULE is: I. Mark the subject(s), any predicate, and the person, number, and tense of each verb, II. Identify the Latin vocabulary you need, and, III. Put the Latin words into the forms you identified in the first step:”

2. Translating from English to Latin, Illustrated

Today’s RULE, English to Latin, Illustrated

| You all prepare well. |

| I. You all (subj.) prepare (2nd pl. pres.) well. |

| II. vōs : parō, parāre : bene |

| III. Vōs bene parātis. (“I put ‘bene’ before ‘parātis’ because of the vocabulary note on ‘bene’, above.”) |

“If a second verb is connected by ‘and’ without a new subject being expressed, then it has the same person and number as the first verb:”

3. English to Latin with One Subject and Multiple Verbs, Illustrated

| I give and love. |

| I. I (subj.) give (1st sg. pres.) and love (1st sg. pres.). |

| II. ego : dō, dare : et : amō, amāre |

| II. Ego dō et amō. |

Exercises 1-8

1. Bona erat ea.

2. Bonum est id.

3. Bonus erit.

4. Tū amās. Sīc cōgitō.

5. Malus est fīlius, nisi parat.

6. When they ask, you give. “‘You’ without ‘all’ after it is always singular.”

7. We think and change, I hope.

8. You all hope and prepare well, but he preserves.

A-Verbs (First Conjugation): Imperfect and Future Tense

A-Verbs: Imperfect Tense

“The imperfect tense, you’ll remember, tells you something was happening in the past. When you see the imperfect, translate ‘was verbing’, or ‘were verbing’.”

“For any A-verb, the imperfect tense is formed from the stem plus -ā- (since it’s an A-verb), followed by -bā- and the personal ending; for example: cōgit-ā-ba-m. The vowel of -bā- shortens before m, t, and nt. Here are the forms for cōgitō, cōgitāre in the Imperfect Tense:”

A-Verb Imperfect Tense Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Meaning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -ā-bam | -ā-bāmus | cōgitābam | cōgitābāmus | I was thinking | we were thinking |

| -ā-bās | -ā-bātis | cōgitābās | cōgitābātis | you were thinking | you all were thinking |

| -ā-bat | -ā-bant | cōgitābat | cōgitābant | he, she, it was thinking | they were thinking |

Irregular dō, dare

“Once again, the verb dō, dare is slightly irregular: its imperfect tense forms have a short -a- (no long mark) after the stem: dabam, dabās, dabat, etc.”

Drill: A-Verbs, Imperfect Tense Conjugation

“Conjugate the verb amō, amāre in the imperfect tense. By ‘conjugate’, I mean provide all six forms (1st, 2nd, 3rd person, both singular and plural) of the verb in the imperfect tense. Use the chart above as a guide.”

| Singular | Plural | |

| 1st person | ||

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person |

Sentence with Imperfect Tense Verb

| The parent was saving. |

| I. The parent (subj.) was saving (3rd sg. imperf.). |

| II. parēns : servō, servāre |

| III. parēns servābat. |

Exercises 9-11

9. When you were loving, I was hoping.

10. We were saving but you all were asking.

11. The daughter was hoping and preparing.

A-Verbs: Future Tense

“Finally, recall how the translation of the future tense in English is ‘will verb’.”

“To form the future tense of any A-Verb, start with the stem plus -ā- (since it’s an A-verb), followed by bo-, bi-, or bu- combined with the personal endings. Here are the forms for cōgitō, cōgitāre in the future tense:”

A-Verb Future Tense Forms

| Ending | Verb Stem + Ending | English Meaning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| -ā-bō | -ā-bimus | cōgitābō | cōgitābimus | I will think | we will think |

| -ā-bis | -ā-bitis | cōgitābis | cōgitābitis | you will think | you all will think |

| -ā-bit | -ā-bunt | cōgitābit | cōgitābunt | he, she, it will think | they will think |

Irregular dō, dare

“The verb dō, dare is again slightly irregular: its future tense forms have a short -a- (no long mark) after the stem: dabō, dabis, dabit, etc.”

Drill: A-Verbs, Future Tense Conjugation

“Conjugate the verb amō, amāre in the future tense. By ‘conjugate’, I mean provide all six forms (1st, 2nd, 3rd person, both singular and plural) of the verb in the future tense. Use the chart above as a guide.”

| Singular | Plural | |

| 1st person | ||

| 2nd person | ||

| 3rd person |

Sentence with Future Tense Verb

| The parent will save. |

| I. The parent (subj.) will save (3rd sg. fut.). |

| II. parēns : servō, servāre |

| III. Parēns servābit. |

Distinguishing Imperfect and Future Tense Forms

“Remember:”

| BA- before the personal ending tells you: imperfect tense. |

| BO-, BI-, or BU- before the personal ending tells you: future tense. |

Exercises 12-14

12. We will ask, and I will hope.

13. The parent will love when the son will prepare.

14. You all will save, unless the twins will give.

A cloud passed in front of the sun, making it cooler, as we switched to another topic.

Object Pronouns

“Next up: objects. An object is the recipient of the action of a verb. In English the object usually comes right after the verb. Suppose I spot my family across the street and they look at me. I might say:”

Examples of Objects

| I (subject) see (verb) my family (object). |

| My family (subject) sees (verb) me (object). |

“The verb sum is an exception – it does NOT have an object. The noun or adjective that comes after the English verb ‘is’ is called the predicate.”

Examples of Predicates

| I (subject) am (verb) Latinitas (predicate). |

| You (subject) are (verb) smart (predicate). |

“But many verbs do have objects. English has special object forms for some pronouns, and so does Latin.”

English Object Pronouns

| Singular | Plural |

|---|---|

| me | us |

| you | you all |

| him, her, it | them |

“Which ones differ from the English subject pronouns?”

Latin Object Pronouns

| Singular | Plural | English Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mē | nōs | me | us |

| tē | vōs | you | you all |

| eum, eam, id | eōs, eās, ea | him, her, it | them (masculine, feminine, neuter) |

“Which ones differ from the Latin subject pronouns?”

“We can now translate sentences that have a verb with an object pronoun. Remember today’s RULE!”

Sentence with an Object Pronoun

| I. Eī eum amant. |

| II. Eī (subj.) eum (obj.) amant (3rd pl. pres.). |

| III. They (subj.) him (obj.) love (3rd pl. pres.). >>> They love him. |

Word Order

“Let’s explain the final step of translation, how we go from ‘They (subj.) him (obj.) love (3rd pl. pres.)’ to ‘They love him’. In English the regular order of words is Subject, Verb, Object (SVO). But in Latin sentences, word order is flexible. When you translate into English, you must change the order to SVO. There can be other words in between, but the subject should come before the verb, and the verb before the object or predicate. Study these examples.”

Translating from Latin to English with SVO Word Order

| I. Eī mē amant. |

| II. Eī (subj.) mē (obj.) amant (3rd pl. pres.). |

| III. They (subj.) love (3rd pl. pres.) me (obj.). |

| I. Tē nōs nōn servābimus. |

| II. Tē (obj.) nōs (subj.) nōn servābimus (1st pl. fut.). |

| III. We (subj.) will not preserve (1st pl. fut.) you (obj.). |

Exercises 18-29

18. Id ego cōgitābam.

19. Id cōgitābam.

20. Ea eum parat.

21. Eam is parat.

22. Is vōs vocat.

23. Eum vōs vocātis.

24. Eam amābitis.

25. Sed ea nōn amābit mē.

26. Tū quoque nōs servābās.

27. Ego ea nōn parābō.

28. Vōs amābāmus.

29. Vōs eae mūtābunt, sī rogābitis.

Infinitives: Subject and Complement

Infinitive as Subject

“Finally, the infinitive of a verb can play a role in a sentence. These are the forms like amāre, spērāre that end with -āre, along with esse, the infinitive of sum. An infinitive can be the subject of another verb, such as est. Its gender is neuter.”

Infinitive as Subject Example

| I. Bonum est parāre. |

| II. Bonum (pred.) est (3rd sg. pres.) parāre (inf.). |

| III. To prepare (inf. subj.) is (3rd sg. pres. (a) good (thing) (pred.). |

Complementary Infinitive

“An infinitive can also complete the meaning of certain verbs, like cōgitō. This is called a complementary infinitive.”

Complementary Infinitive Example

| I. Dare cōgitō. |

| II. Dare (inf.) cōgitō (1st sg. pres.). |

| III. I plan (1st sg. pres.) to give (inf.). |

Infinitive Taking an Object

“And the infinitive can have its own object. In the next example, tē is the object of servāre, which is the complementary infinitive of the conjugated verb cōgitābāmus:”

Infinitive Taking an Object Example

| I. Tē servāre cōgitābāmus. |

| II. Tē (obj.) servāre (inf.) cōgitābāmus (1st pl. imperf.). |

| III. We were planning (1st pl. imperf.) to save (inf.) you (obj.). |

Exercises 30-33

“Each of these sentences has two verbs, one conjugated main verb with a personal ending, and one infinitive.”

30. Bonum erit amāre.

31. Parāre tē cōgitāmus.

32. Parāre nōs cōgitās.

33. You all will plan to change me.

Translating Cato

“So, let’s return to Cato’s original sentence, which begins: Praedium cum parāre cōgitābis....”

“The farm, praedium, is the object. Parāre is an infinitive. The 2nd person singular ending of cōgitābis tells us that the subject is ‘you’, and the verb is future tense:”

I. Praedium cum parāre cōgitābis...

II. Praedium (obj.) cum parāre (inf.) cōgitābis (2nd sg. fut.)...

III. When you will plan (2nd sg. fut.) to acquire (inf.) a farm (obj.)…

Supplying ‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’ in English Translation

“Notice in the last step how I added ‘a’ to the noun praedium, ‘farm’. Latin does not have ‘a’ or ‘an’ or ‘the’, but you should add these words in English where they seem to be needed. Likewise, when you translate a sentence from English into Latin, you cannot translate ‘a’, ‘an’, or ‘the’.”

Exercise 34

“Use Cato’s phrase as a model for this next sentence. Do not express the subject pronouns when you translate into Latin:”

34. When you were planning to acquire a farm, I was hoping to change you.

With that, we finished. As we were walking away, we heard a man inside the villa continue the argument: Prīmō locō est glandāria silva cum porcīs! As the building receded in the distance, Latinitas grew more reflective, thinking about history instead of grammar.

“Some bits of the Roman past are gone forever. A decade after Cato died, this villa experienced a fire and burned to the ground. The owners rebuilt it on the same foundations, and it survived another six hundred years, only to be sacked by raiders from the north of Italy. Later, the locals stripped the ruins of useful building materials; what was left at that point was overgrown by weeds and trees. But there are still hundreds of villas just like Cato’s in this part of Italy – not as old, but very similar in design, with the same scalloped rooftiles. Their owners still grow the same crops, with a few new additions – tomatoes, peppers, eggplants – from the New World. Pigs still roam the oak forests. And the fruits, olives, cheeses, and wines that this soil still produces – who can describe how heavenly they are?”

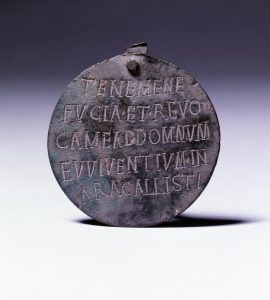

4. A copper plate that may have been attached to the collar of an enslaved person working on a farm. The inscription reads Tenē mē nē fugia(m), et revocā mē ad dom(i)num Euviventium in ār(e)ā Callistī, which means ‘Hold me so I don’t flee, and bring me back to my master Euviventius, on the estate of Callistus.’

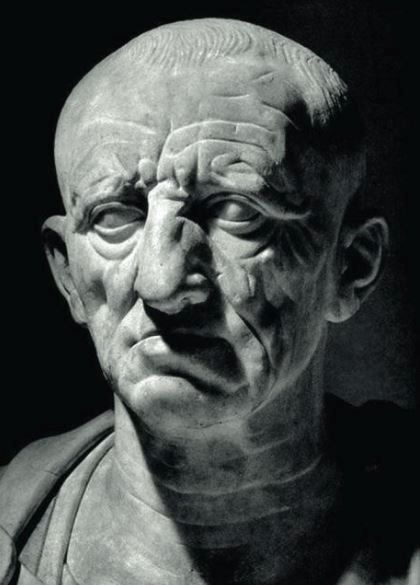

5. A marble bust of a Roman pater or father, the so-called ‘Patrician Torlonia’. It was once thought to depict Cato the Elder, but now the identity of the subject is considered unknown. First-century CE. Notice how the sculptor realistically depicted his wrinkles and age, rather than trying to represent him more youthfully.