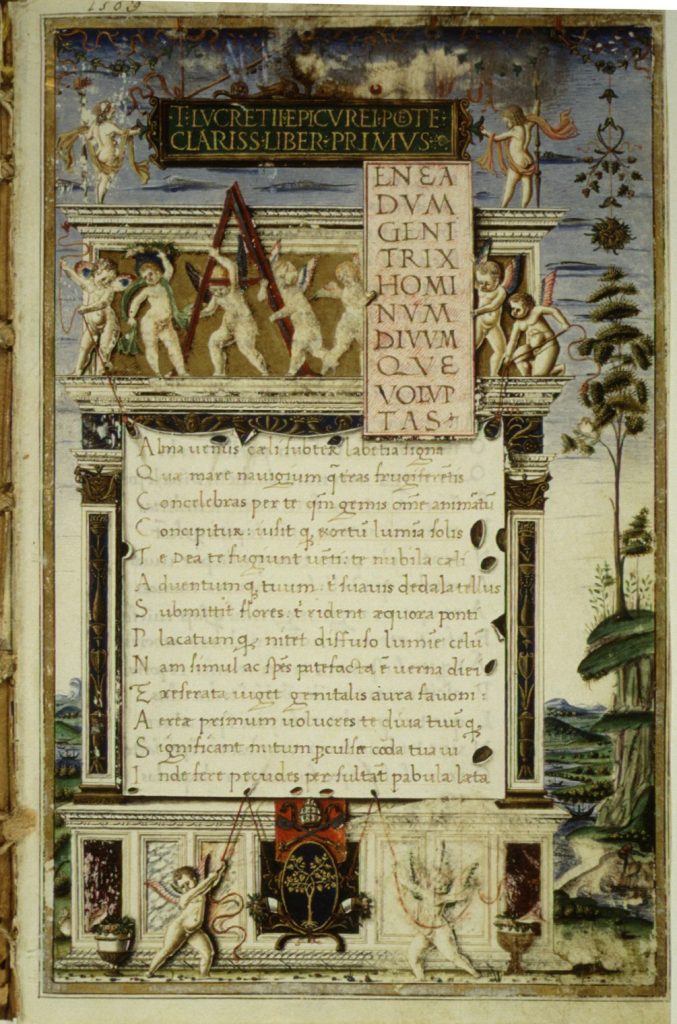

14. A manuscript, written in 1483, of Lucretius’ poem Dē Rērum Nātūrā. The title at the top reads T(itus) Lucrētiī Epicūreī poēt(a)e clāriss(imī) liber prīmus, ‘Of Titus Lucretius the Epicurean, the most famous poet, the first book.’ The first line reads Aeneadum genetrix, hominum dīvumque voluptās, ‘Matriarch of the Aeneas family, pleasure of men and gods…’, referring to the goddess Venus.

Explōrātiō Septima (VII) Adventure Seven

Lucretius, Dē Rērum Nātūrā, Excerpt

Plural Noun Forms: Nominative, Genitive, and Accusative Plural, Declensions 1-5

Nominative, Genitive, Accusative Plural Endings, Declensions 1-5

Review of Case Endings, Declensions 1-5

Introduction to Adjective Declension

Formation of US-A-UM Adjectives (First and Second Declension Adjectives)

Agreement of Adjective and Noun

US-A-UM Adjectives Modifying and Agreeing with Nouns, Examples

Reading: Epicurus and the Garden

Lucretius, Dē Rērum Nātūrā, Excerpt

Where and When Are We Today?

Campus Mārtius, Rōma

Mēnsis Iānuārius

L. Domitiō Ahēnobarbō Ap. Claudiō Pulchrō cōnsulibus

Campus Martius, Rome

January, 54 BCE

Bundle up,” she said. “Last night was as cold as it gets in Rome, almost freezing. The park we are going to has walls, but they only slow the wind, they don’t stop it.”

I closed my eyes and took a sip of the drink. Today it tasted horribly bitter, a bitterness only partially offset by a dab of honey smeared on the rim of the glass. After I blinked, I felt a chill air on my face. We were in a large park, with fountains and leafless trees laid out in tidy rows, hemmed in on all four sides by porticūs, porticoes, rows of columns with covered walkways. We were standing behind a group of people who were all facing a large stack of firewood. On top of it there was a blanket wrapped around a corpse, and I realized: this was a funeral. The attendees were of about the same age, and it struck me that they were probably the dead man’s friends. Most had the well-fed look of upper-class Romans, yet they wore the simple wool and linen garments of the plebs. About two dozen men and four women stood there, holding hands or with their arms around each other’s backs; one, to judge by his tattoos and branding scars, either was or had been a servus, a slave.

Lucretius and the Epicureans

“These are members of the Epicurean community,” she whispered. “This is a funeral for their friend, the poet Titus Lucrētius Cārus. Notice they are all smiling, or trying to. Not the usual behavior for Romans at a funeral! There is a reason for this.”

“Epicurus, the Greek philosopher whose teachings they follow, taught a simple creed based on a handful of basic principles: that the basic needs of life are easy to meet; that things that seem frightening can, with mental practice, be overcome; and that gods are nothing we should fear. He argued that the world is made up of atoms, created without any help from the gods, and that the soul is a kind of vapor, which dissipates when people die. Perhaps his most important teaching was that death is not a thing people should worry about, since nothing of a person is left behind that can suffer. The only correct attitude toward death is to consider it completely irrelevant; timor mortis, fear of death, is to be confronted and eliminated. People should enjoy the lives they have, avoid the violent world of politics, and build a societātem amīcōrum, a society of friends – hence,” and she gestured to the group in front of us, its members leaning against each other to keep off the cold, “these are Lucretius’ dear companions, seeking to mark his death in a manner consistent with Epicurean teaching. Lucretius meant a lot to them as a person, and he was, in addition, a genius of a poēta.”

The pyre was lit and sprang quickly to life, offering a welcome blast of warmth. As the flames crackled and roared, one man stood before them and began to read lines of poetry from a scroll:

Lucretius, Dē Rērum Nātūrā, Excerpt

1) Ē tenebrīs tantīs tam clārum extollere lūmen

quī prīmus potuistī inlustrāns commoda vītae,

tē sequor, ō Grāiae gentis decus, inque tuīs nunc

ficta pedum pōnō pressīs vestīgia signīs.

“To raise so bright a lamp above such darkness,

you were the first who could do so, shining a light on the conveniences of life:

and you I follow, o pride of the Greek nation, and now

in the marks you made I plant and fix my footsteps.”

“What he is doing,” she explained to me, “is very appropriate. He is reading from the third book of Lucretius’ long poem, dē Rērum Nātūrā, On the Nature of Things. The poem is an introduction to Epicurean philosophy in verse, and this book opens with Lucretius’ tribute to Epicurus. The reader is reusing it as a tribute to Lucretius himself.”

He went on:

2) nōn ita certandī cupidus quam propter amōrem

quod tē imitārī aveō; quid enim contendat hirundō

cycnīs, aut quidnam tremulīs facere artubus haedī

consimile in cursū possint et fortis equī vīs?

“It is not so much from a desire to challenge as it is from love

that I yearn to copy you. For how could a swallow compete

with swans, or how could baby goats with trembling limbs

do anything on a racecourse like the force of a mighty horse?

3) tū, pater, es rērum inventor, tū patria nōbīs

suppeditās praecepta, tuīsque ex, inclute, chartīs,

flōriferīs ut apēs in saltibus omnia lībant,

omnia nōs itidem dēpāscimur aurea dicta,

aurea, perpetuā semper dignissima vītā.

You, father, are the discoverer of facts, you provide us with

a father’s rules, and from your famous papers,

like bees sipping everything in meadows full of flowers,

we feed upon your words, all of them like gold,

golden, and always most worthy of ongoing life.

4) nam simul ac ratiō tua coepit vōciferārī

nātūram rērum, dīvīnā mente coorta,

diffugiunt animī terrōrēs, moenia mundī

discēdunt…

“For as soon as your reason has started to give voice to

the nature of things – a reason rising from a godlike mind –

the terrors of the mind scatter, and the walls of this world

go away…”

After finishing the introduction, he went on to read Lucretius’ explanation of how the soul is made out of atoms and cannot survive apart from the body. He concluded with a passage where Lucretius brought in Nature herself to teach a final lesson about acceptance of life’s limits:

“Finally, what if the Nature of Things, Rērum Nātūra, suddenly got a voice,

and personally criticized one of us like this –

‘What is the reason, mortal being, why you indulge in sick grief

so much? Why do you groan and weep for death?

For if you are grateful for what you’ve lived, your life so far,

and if all the goods you possessed have not washed away and vanished

unappreciated, as if stuffed into a bucket full of holes,

why then don’t you leave like a dinner guest, full of life, plēnus vītae,

and take your carefree rest with a mind at peace, you fool?”

We could see the Epicureans working hard with their feelings, struggling to confront and overcome the natural human loathing of non-existence, the desire for a life that goes on and on forever. When the reading came to an end, the flames on the pyre had largely burned themselves out; the participants exchanged hugs and kisses, and they broke up into two groups to go home. A pair of teenage boys, intrigued by the proceedings, attached themselves to one group and began to ask them questions. The other group raised their cloaks over their heads and broke into a jog after an old woman taking a stroll with her son began to throw rocks at them, calling them atheists and impiī, impiī, impious, unreligious folks.

That was my introduction to the Epicureans. To escape the cold we retreated to an official-looking building set into of one the porticoes, climbing its stone steps. Latinitas explained that this place was meant to be an alternative venue for Senate meetings when it was finished. Construction was ongoing, and some craftsmen were still busy carving and polishing its stones. One team was applying paint to the hair and clothing of a larger-than-life statue of a Roman general: Pompēius Magnus, Pompey the Great, who was the patron of this whole complex, she explained. We availed ourselves of the workers’ portable fireplaces, and sat down to study.

“Let’s start with some common nouns that are relevant to Epicureanism and Lucretius’ poem:”

Vocabulary

First Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| anima, anim-ae | f. | soul |

| causa, caus-ae | f. | cause |

| nātūra, nātūr-ae | f. | nature |

| poena, poen-ae | f. | penalty; punishment |

Third Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| pater, patr-is | m. | father |

| māter, mātr-is | f. | mother |

| parēns, parent-is | m. / f. | parent |

| homō, homin-is | m. / f. | human being; person |

| ratiō, ratiōn-is | f. | reason; method |

Third Declension Nouns (I-Stems)

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| gēns, gent-is | f. | family line; clan; nation |

| mēns, ment-is | f. | mind; will |

| ars, art-is | f. | art; skill |

| pars, part-is | f. | part |

| fīnis, fīn-is | m. | end; goal; plural: territory |

Plural Noun Forms: Nominative, Genitive, and Accusative Plural, Declensions 1-5

“Today we will switch from singular to plural noun forms. Plural noun forms are distinguished from singular forms by different endings, just as plural forms are in English. English plurals often end with ‘s’, but other small changes can occur (for example: life, lives).”

“Latin plurals for the nominative, genitive, and accusative cases are also formed by adding different endings to the stem.” In the air she sketched this chart for me:

Nominative, Genitive, Accusative Plural Endings, Declensions 1-5

| 1st Decl. | 2nd Decl. | 3rd Decl. | 3rd Decl. I-Stems | 4th Decl. | 5th Decl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | -ae | -ī | -ēs | -ēs | -ūs | -ēs |

| Genitive | -ārum | -ōrum | -um | -ium | -uum | -ērum |

| Dative | ||||||

| Accusative | -ās | -ōs | -ēs | -īs/-ēs | -ūs | -ēs |

| Ablative |

“Note the following about these endings:”

“In the 4th, 5th, and regular 3rd declension, the nominative and accusative plural forms are the same.”

What’s the difference between regular 3rd declension nouns and i-stem ones?

Third Declension I-Stem Nouns

“There are some 3rd declension nouns that often have -īs in the accusative plural instead of -ēs and that have -ium in the genitive plural. These are called i-stem nouns. Of the nouns you have learned so far, the following are i-stems:”

Third Declension I-Stem Nouns, Examples

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| mors, mort-is | f. | death |

| urbs, urb-is | f. | city |

| nox, noctis | f. | night |

| gēns, gent-is | f. | family line; clan; nation |

| mēns, ment-is | f. | mind; will |

| ars, art-is | f. | art; skill |

| pars, part-is | f. | part |

| fīnis, fīn-is | m. | end; goal; plural: territory |

“Do not worry too much about distinguishing regular from i-stem 3rd declension nouns. The Romans themselves got confused with these! It’s more important that you can correctly identify the case and number of a word form in a sentence, so just remember that certain 3rd declension nouns will exhibit the variants noted above.”

“For each noun you now know eight forms.”

Review of Case Endings, Declensions 1-5

| Singular | 1st Decl. | 2nd Decl. | 3rd Decl. | 3rd Decl. I-Stem | 4th Decl. | 5th Decl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | vi-a | amīc-us | rēx | urbs | man-us | r-ēs |

| Gen. | vi-ae | amīc-ī | rēg-is | urb-is | man-ūs | r-eī |

| Dat. | vi-ae | amīc-ō | rēg-ī | urb-ī | man-uī | r-eī |

| Acc. | vi-am | amīc-um | rēg-em | urb-em | man-um | r-em |

| Abl. | vi-ā | amīc-ō | rēg-e | urb-e | man-ū | r-ē |

| Plural | ||||||

| Nom. | vi-ae | amīc-ī | rēg-ēs | urb-ēs | man-ūs | r-ēs |

| Gen. | vi-ārum | amīc-ōrum | rēg-um | urb-ium | man-uum | r-ērum |

| Dat. | ||||||

| Acc. | vi-ās | amīc-ōs | rēg-ēs | urb-īs/-ēs | man-ūs | r-ēs |

| Abl. |

Drill Noun Case Forms

“Provide the seven other forms that you’ve learned (genitive, dative, accusative, ablative singular; nominative, genitive, accusative plural) for the following nouns, which are given in the nominative singular form. To do so, first identify the declension to which the noun belongs (see How to Identify the Declension of a Noun in Explōrātiō IV), then identify the stem of the noun based on the genitive-stem rule (see Explōrātiō IV), and finally add the correct case ending to the stem.”

| Singular | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | patria | populus | vōx | gēns | senātus | fidēs |

| Gen. | ||||||

| Dat. | ||||||

| Acc. | ||||||

| Abl. | ||||||

| Plural | ||||||

| Nom. | ||||||

| Gen. | ||||||

| Dat. | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) |

| Acc. | ||||||

| Abl. | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) | (not yet learned) |

“Now try these sentences.”

Exercises 1-12

1. Parentēs sumus, et fīlium ūnum habēmus.

2. Hominēs dolōrem et poenās timent.

3. Nīl mors est ad nōs.

4. Tū, pater, es rērum inventor.

5. Docē nōs, māter, causās rērum.

6. Timōrēs animam rēgis movēbant.

7. Epicūrus nōs bene cōgitāre dē vītae fīne docēbit.

8. Ratiō virōs ā furōre ad lūcem vocābat.

9. Part of the clan hopes, but we fear.

10. Friends will have trust. Enemies have fear.

11. The end of the night will remove (removeō, removēre) the pains of love.

12. The arts of love see the causes of the passions. “Hint: animus in the plural means ‘passions’.”

Introduction to Adjective Declension

“Let’s stay a bit longer. We’re going to add to your vocabulary by talking about adjectives now. An adjective is a word that describes a noun or pronoun: that it is warm, bright, or belongs, say, to me: warm fire, bright fire, my fire – those are adjectives describing a fire.”

“English adjectives usually have just one form. Latin adjectives, by contrast, have forms that tell you number and case. They are like Latin nouns in that respect, but, unlike Latin nouns, they can be any gender – masculine, feminine, or neuter. We’ll learn why this is so in a moment. When an adjective is introduced in the dictionary, it will typically show three words that are the masculine, feminine, and neuter nominative singular forms, like so:”

Vocabulary

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| meus, me-a, meum | my (masculine, feminine, neuter) |

| tuus, tu-a, tuum | your (masculine, feminine, neuter) |

| dīvīnus, dīvīn-a, dīvīnum | divine (masculine, feminine, neuter) |

| magnus, magn-a, magnum | great (masculine, feminine, neuter) |

Formation of US-A-UM Adjectives (First and Second Declension Adjectives)

“These adjectives I call US-A-UM adjectives after their nominative singular endings. The stem of such an adjective can be found by removing the -a from the feminine nominative singular form. To remind you of this, I want you to write a dash between the stem and the -a.”

“You actually already know many of the forms of US-A-UM adjectives: the masculine form follows the same pattern as 2nd declension masculine nouns (words like amīcus, amīcī, m.), and the feminine form follows the pattern of 1st declension nouns (words like vīta, vītae, f.).”

Agreement of Adjective and Noun

“Adjectives, like chameleons, copy the gender, case, and number of their associated noun. Remember that: an adjective must agree with its noun in gender, case, and number!”

“Since the gender of the adjective needs to match whatever noun it goes with, first identify the gender of the noun, and this will tell you the gender and declension pattern for the adjective:”

US-A-UM Adjective Form based on the Gender of the Noun in Agreement

| Noun Gender | US-A-UM Adjective Declines Like: |

|---|---|

| Feminine | 1st declension noun |

| Masculine | 2nd declension masculine noun |

“You actually know one example of an adjective going with a noun already: rēs pūblica. Rēs is a noun, and pūblica is an US-A-UM type of adjective. The noun is feminine, so the endings of pūblica are 1st declension endings. Literally, the phrase means ‘public thing’ or, better, ‘the people’s property’.”

“An adjective also must have the same case as its noun, and the same number. So, if I wanted to use ‘republic’ in the genitive singular, I’d say reī pūblicae: the noun is feminine, genitive, singular, and so is the adjective. Note that rēs is a 5th declension noun, so its endings look different from those of pūblica. The form reī pūblicae is correct, because both words are feminine, genitive, and singular.”

“In the following examples, ars is feminine, and that is why ‘my’, meus, -a, -um, declines like a 1st declension noun, starting with the nominative singular mea. Homō is masculine, and that is why ‘great’, magnus, -a, -um, declines like a 2nd declension noun, starting with the nominative singular meus. There are no new endings to learn. But you must get used to adjectives sometimes modifying nouns even though their endings are not spelled the same:”

US-A-UM Adjectives Modifying and Agreeing with Nouns, Examples

| ars, artis, f. + meus, me-a, meum | homō, hominis, m. + magnus, magn-a, magnum | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nom. | ars mea | artēs meae | homō magnus | hominēs magnī |

| Gen. | artis meae | artium meārum | hominis magnī | hominum magnōrum |

| Dat. | artī meae | hominī magnō | ||

| Acc. | artem meam | artēs meās | hominem magnum | hominēs magnōs |

| Abl. | arte meā | homine magnō |

Translating Adjectives

“Once you’ve determined that a noun is modified by an adjective in agreement, you simply translate the two together based on your knowledge of their case and number. For example, ars mea (nominative singular) would be ‘my art’ as the subject or predicate of a sentence; artēs meae (nominative plural) would be ‘my arts’ as the subject or predicate of a sentence; hominis magnī (genitive singular) would be ‘of a great person’; hominī magnō (dative singular) would be ‘to/for a great person’.”

“Adjectives in Latin often come immediately after their nouns. When they don’t, this can sometimes indicate a difference in meaning. For example, when magnus means large in size or amount, it comes before its noun; when it means important or awesome, it often comes after. The phrase magna urbs means a big city. The nickname Pompeius Magnus means that Pompey is awesome, not big.”

Exercises 13-17

“Write out the Latin and English of these phrases in the eight case and number combinations that you know now, just like we did for ‘my art’ and ‘great person’ in the chart above:”

13. patria, patriae, f. + meus, me-a, meum

14. furor, furōris, m. + dīvīnus, dīvīn-a, dīvīnum

15. senātus, senātūs, m. + magnus, magn-a, magnum

16. gēns, gentis, f. + tuus, tu-a, tuum

Vocabulary

“Add this adverb and these three conjunctions to your vocabulary:”

| Latin | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| semper | always |

| aut | or |

| nam | for (explaining why) |

| enim | for (explaining why); indeed “This word almost always comes second in a sentence.” |

“Both of the conjunctions nam and enim mean ‘for’, but not as a preposition before a noun. Instead, they introduce explanations: ‘I need water, for I am thirsty’; ‘I need to remain, for thus the goddess orders me’. In Latin the last sentence would be either Manēre dēbeō, nam dea sīc mē iubet, or Manēre dēbeō; sīc enim dea mē iubet.

Exercises 17-22

“Now attempt to translate these, too:”

17. Mūtā iam tuam mentem, Catilīna; nam vōcēs cōnsulum tē iubent.

18. A good person fears the divine light of the gods and goddesses.

19. Sine ratiōne bonā pars magna populī mātrem rēgis semper amābat.

20. Without reason or cause the kings were ordering him to prepare the men for (use ad) death.

21. Ratiō mea mentēs magnas, mentēs hominum magnōrum, docēbit; Lucrētius enim sum.

22. Is my behavior good? What do you all think? “Remember: ‘behavior’ is mōs in the plural form.”

Reading: Epicurus and the Garden

Graecus erat Epicūrus. Graecus ab Samō erat. Epicūrus multās urbēs et multōs hominēs vidēbat. Epicūrus hominēs docēbat. Et virōs et fēminās docēbat. Athēnīs scholam condidit. Scholam vocābat ‘hortum’. Epicūrus et amīcī vīvēbant in hortō. In hortō amīcōs Epicūrus docēbat. Quid docēbat? Epicūrus et amīcī Epicūrī multa docēbant.

Gracecus Greek Samō Samos (an island in the eastern Aegean sea) multās many multōs many Athēnīs in Athens scholam school condidit he established hortum garden vīvēbant were living multa many things

Malus est dolor. Causa dolōris est timor. Nōs hominēs habēmus timōrēs multōs. Mortem timēmus. Deōs deāsque timēmus. Eōs timēmus nam poenās timēmus. Multa timēmus. Sed nōs mortem timēre nōn dēbēmus. Nīl mors est ad nōs. Poenās quoque timēre nōn dēbēmus. Bonī sunt dī, et bonae sunt deae. Dī deaeque nōn multant nōs poenīs.

multant punish poenīs with punishments

Bona est voluptās. Voluptās est vīta sine dolōre aut timōre. Sunt mala in vītā. Sed nōs mala tolerāre possumus. Sī mala tolerāmus, vītam sine dolōre aut timōre habēbimus. Sī voluptātem petimus, vītam bonam habēbimus.

voluptās pleasure mala bad things; ills tolerāre to tolerate possumus we are able petimus we seek

Lucretius, Dē Rērum Nātūrā, Excerpt

“Now fill in the blanks in the translation of these lines of Lucretius, and adjust to the required English word order:”

|

Nam |

simul ac |

ratiō |

tua |

coepit |

vōciferārī |

|

|

as soon as |

|

|

began (3rd sg.) |

to give voice to (inf.) |

|

nātūram |

rērum, |

dīvīnā |

mente |

coorta, |

|

|

, |

from... |

|

rising (adj., fem. nom. sg.), |

|

diffugiunt |

animī |

terrōrēs, |

moenia |

mundī |

|

flee away (3rd pl. pr.) |

(gen. sg.) |

(nom. pl.), |

the walls (nom. pl.) |

of the world (gen. sing.) |

|

discēdunt. |

|

go away (3rd pl. pr.) |

When we were done, we walked back through the Porticus Pompēiī. Like a tour guide, Latinitas explained to me that Pompey the Great ordered and had overseen the construction of this complex, paying for it out of his own pocket; after leading Roman armies to victory over countless nations and kingdoms in the eastern Mediterranean – Pontus, Armenia, Cappadocia, Syria, Phoenicia, Judaea, Nabataea – Pompey had become rich from plunder. She also drew my attention to the paintings and statues under the porticoes. There were hundreds of famous works of art from Greece, most of them stolen and carried back to Rome. Looking at them, I could feel the intense Roman love of Greek art – and the indignation of the Greeks, whose beloved treasures were stolen.

At the far end of the park we entered a tall but nondescript building. The interior looked like the back room of a theater. Sure enough, when we passed outside again, we were standing at the end of a long stage, nearly 300 feet long. Rising before us were dozens and dozens of rows of seats arranged in semicircles. In size and layout it was just like theaters I had been to – but it was much more beautiful. All of the columns and supports were made of colored stone and marble. High up on the top row of the seats sat an entire temple. It had an inscription on it, from which I could make out the words VENERIS, ‘of Venus’, and POMPEIVS MAGNVS CONSVL. It was a temple for Venus, dedicated, like the theater and the park, by Pompey the Great as consul.

Instead of a roof, the theater had a timber framework, over which massive tapestries were draped, each one the size of a ship’s sail. Woven into them in gorgeous red and yellow colors were animals, tragic masks and comic masks, and stylized pictures of Pompey riding in a triumphal chariot. The material they were made of was thin, and the sunlight shining through them cast their color over everything below; when the wind gusted, the tapestries rippled and the colors swept in waves over the seats.

“This was one of Lucretius’ favorite places,” Latinitas remarked, “the Theātrum Pompēiī. He loved to come here to watch plays – tragedies, comedies, mimes. The architecture and the colors impressed him as much as it impresses you. He even described in his poem the way in which, when the sun is shining, these awnings change the look of everything beneath them.”

The whole place was painfully beautiful to look at, and so real. And as I looked at the massive stone weight of it and the intricate, lively detailing, I thought about the sweat, the labor, and the pain that went into making it, and all the patient artistry expended by thousands of human beings I would never see with my eyes, much less learn their names. Yet I could see their work – I was totally surrounded by it, overwhelmed and blown away by it. And then it came to me, as Latinitas suggested, to see it as an act of assertion on their part, resistance through generosity, as if to say to all who would visit it: here is something beautiful which we human beings made, a beauty that we somehow managed to tap despite our misery, a bit of pride for those of us whose lives are one long humiliation, something which we crafted, not for those who oppressed us, but for those who would appreciate and make use of it, in any age.

This way of looking at things resolved the conflicts I felt somewhat, and when I returned home and fell asleep, I had a dream of actors walking across the stage, removing their masks, looking at me, nodding, squinting, then moving silently on.

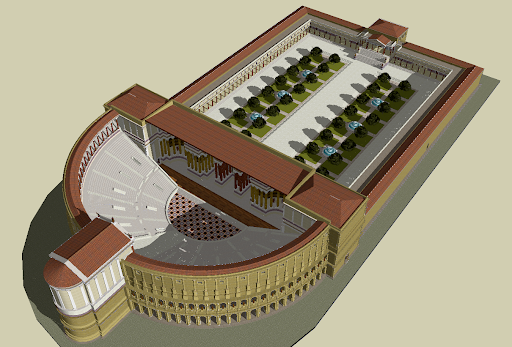

15. A reconstruction of the Theātrum Pompēiī and the enclosed hortī or ‘gardens’ that were connected to it. In the lower left-hand corner at the top of the cavea or seating area you can see the temple of Venus; in the upper right is the building where Julius Caesar was assassinated.

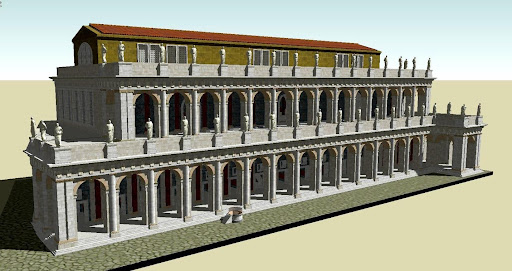

16. A reconstruction of a Roman basilica, the Basilica Aemilia, in the Forum Rōmānum, the Roman Forum. Courts met and assemblies would be held within them, and merchants might also use their spaces. Christian churches were modelled on the design of the basilica.