76. Saint Jerome in a Cave, a woodprint by Albrecht Dürer, 1512. According to legend, Jerome removed a thorn from the paw of a leō or lion he found wandering near his cave, and out of gratitude the lion became his protector and pet.

Explōrātiō Trīcēnsima Quīnta (XXXV) Adventure Thirty-Five

Formation of the Future Perfect Active

Translating the Future Perfect Tense

Formation of the Future Perfect Passive

Formation of the Perfect Active Subjunctive

Formation of the Perfect Passive Subjunctive

Translation of the Perfect Subjunctive

Distinguishing the Perfect Subjunctive and Future Perfect Active

The Future Perfect of Defective Verbs

Synopsis of the Perfect System

Indicative Verbs in Conditional Sentences

Present or Perfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences

Imperfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences

Pluperfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences

Jerome, Vulgate Bible, Book of Genesis Excerpt

Jerome, Vulgate Bible, First Book of Corinthians Excerpt

Where and When Are We Today?

Bethleem, Palaestīna

Mēnsis September

Flāviō Anthemiō Flāviō Stilichōne cōnsulibus

Bethlehem, Palestine

September 405 CE

I was still shaking my head at what happened to Vegetius when Latinitas returned the next day. Because he wanted to reform the Roman army, he devoted years of his life to researching and writing a book, and sailed all the way across the Mediterranean looking for a commission. And what did he get for his efforts? A measly reward that would barely cover the cost of his travel expenses. I was peeved at Theodosius, and at all the so-called ducēs and principēs we had encountered or read about. They seemed to me then – and still seem to me, sometimes – like nothing more than a pack of callous, power-hungry psychopaths. Fortunately Latinitas broke me out of my dark mood with a new gift.

“Here,” she said, “I brought you something. It’s this vestis, made by one of my favorite designers.”

It was a light linen tunica with ties on the back and short sleeves. It was just like most of the tunics I had seen people wear, except it had a thin crosshatch pattern stitched around the hem. Once I threw it on she inspected it for fit and gave me an approving nod.

It fits wonderfully, thank you, I told her. Can I wear it today? It was warm outside, but I was not sure how warm it would be where we were traveling.

“Of course. I noticed your purple bathrobe was starting to look rather ratty. Do you ever wash it?”

Of course I wash it, I said, trying to remember the last time I did. At least once a year, I said.

“You will look good in it. People will look at you and think you are just a commoner. No one will mistake you for the offspring of royalty anymore.”

The instant she said that, its significance suddenly hit me. The child’s voice, purpureā istā cum togā rēgālis vidēre esse, ‘In that purple toga you seem to be royalty!’ But no, no, I was not royalty. I wasn’t and I didn’t want to be and did not want to be perceived as such. What I really wanted was to visit the ancient world and be taken for an ordinary person. And now I had the right clothes to do so. I was pleased with this development. It felt right, like I had found something I had been looking for for a very long time without knowing it.

The wine she gave me today smelled a bit like rosemary. It landed us in a dry, mountainous land, which, I was given to understand, was the province formerly called Jūdaea, but renamed Palaestīna after the Romans crushed the Jewish revolt. We were just south of Jerusalem, in a small, famous town named Bethlehem. According to Christian tradition, it was here that Jesus was born. His birth is celebrated in December, although he was actually born in September (so Latinitas said).

Jerome

Bethlehem was a small town, and already an active tourist destination, with peregīnī, or pilgrims, coming from all over to visit. Our purpose was somewhat different, however. Latinitas wanted me to see a certain holy man. His name in Greek is Hieronymus, but in English he is more often referred to by the name Jerome, and since he was later sainted, Saint Jerome.

We walked out of town along a ridge line, then turned off to scamper down a slope, while I tried to keep my footing on the round stones. At the bottom there was a cave; its entrance was decked out with stone walls and a roof to make a rather comfortable-looking residence, nestled into the rock.

We took a seat under a nearby palm tree while I adjusted my sandals. “That is Jerome’s cave,” she explained. “After a long and busy career in the Church, he decided to spend the rest of his life here working on a translation project – I will show it to you later when he steps out for a walk.”

“Today, in addition to getting a new tunic, you are going to finish learning all the regular Latin verb forms.”

I looked at my notebook. There were only a few pages left; we were getting close to the end.

“The forms that remain for you to learn are the future perfect indicative and the perfect subjunctive.”

The Future Perfect Indicative

“The future perfect tense is the sixth Latin verb tense. As its name indicates, it combines future and perfect tense features.”

Formation of the Future Perfect Active

“The future perfect active is formed on the perfect stem, to which the future tense forms of the verb sum – erō, eris, etc.– are attached as personal endings; the one exception is that -erint is used for the third-person plural, instead of -erunt. The basic translation is ‘will have verbed’ – ‘I will have verbed, you will have verbed’, and so on.”

Formation of the Future Perfect Active

| Latin Form Singular | Latin Form Plural | English Meaning Singular | English Meaning Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| amāverō | amāverimus | I will have loved | we will have loved |

| amāveris | amāveritis | you will have loved | you all will have loved |

| amāverit | amāverint | he, she, it will have loved | they will have loved |

Future Perfect Tense Example

“Tacē, Lucrētia" inquit; "Sextus Tarquinius sum; ferrum in manū est. Moriēre, sī ēmīseris vōcem.”

“Be silent, Lucretia”, he said; “I am Sextus Tarquinius; there is a sword in (my) hand. You will die, if you will have let out a word.”

Translating the Future Perfect Tense

“Since English does not use this tense as much as Latin does, sometimes it is best to translate the future perfect as a future tense verb that has emphasis. You can do this by adding ‘yes’, for example – amāverō, ‘yes, I will love’, or by putting emphasis on the verb ‘will’ ‘I will love’.”

Formation of the Future Perfect Passive

“The future perfect passive is formed using the nominative of the perfect passive participle (fourth principal part of the verb) together with the future forms of sum – erō, eris, etc. Latin speakers sometimes use the future perfect of sum – fuerō, fueris, etc. – instead of erō, eris, to make the meaning even more emphatic.”

Formation of the Future Perfect Passive

| Latin Form | Latin Form | English Meaning | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural |

| amātus, -a, -um erō / fuerō | amātī, -ae, -a erimus / fuerimus | I will have been loved | we will have been loved |

| amātus, -a, -um eris / fueris | amātī, -ae, -a eritis / fueritis | you will have been loved | you all will have been loved |

| amātus, -a, -um erit / fuerit | amātī, -ae, -a erunt /fuerint | he, she, it will have been loved | they will have been loved |

Exercises 1-2

1. Tot virī bonī inventī fuerint sī summō studiō cūrāque quaerēs.

2. Nihil tibi litterae meae prōsunt sī tū eās nōn accēperis.

The Perfect Subjunctive

“Now to the last of the subjunctive tenses: the perfect.”

Formation of the Perfect Active Subjunctive

“The perfect active subjunctive is formed by adding to the perfect stem of the verb (third principal part) the sequence -eri- followed by the personal endings.”

Formation of the Perfect Active Subjunctive

| Singular | Plural |

|---|---|

| amāverim | amāverimus |

| amāveris | amāveritis |

| amāverit | amāverint |

Formation of the Perfect Passive Subjunctive

“The perfect passive subjunctive is made by replacing the indicative forms of sum in the perfect passive indicative with the subjunctive ones – sim, sīs, etc.”

Formation of the Perfect Passive Subjunctive

| Singular | Plural |

|---|---|

| amātus, -a, -um sim | amātī, -ae, -a sīmus |

| amātus, -a, -um sīs | amātī, -ae, -a sītis |

| amātus, -a, -um sit | amātī, -ae, -a sint |

Translation of the Perfect Subjunctive

“The perfect subjunctive generally has either of two translations, depending on the context. In an indirect question or a result clause, it can be translated like the corresponding perfect indicative form, consistent with the rules you learned before.”

Indirect Question Example

Nōn possum dīcere quantum animō vulnus accēperim.

I am not able to say how great a wound I received in my mind.

Result Clause Example

Tanta fuit turba ut nēmō intellegere verba dīcentis potuerit.

The crowd was so big that no one was able to understand the words of the speaker.

“The perfect subjunctive occurs as the main verb in an independent clause in jussive and potential constructions. A perfect tense potential subjunctive adds emphasis. Translate it as you would a present subjunctive; you can add ‘yes’ to the verb, or ‘no’, if it is a negative sentence.”

Potential Subjunctive Example

Accēperim id. Yes, I could receive it.

perfect tense accēperim is translated like the present subjunctive

“A perfect tense jussive subjunctive occurs in the second person with nē as a form of prohibition. Translate it like a negative command.”

Jussive Subjunctive Prohibition Example

Nē flūmen trānsieris. Do not cross the river.

“A perfect tense jussive subjunctive can also indicate a concession; translate it as you would the corresponding perfect indicative form with ‘granted,’ or ‘yes’.”

Jussive Subjunctive Concession Example

“Malus cīvis fuit.” “Fuerit aliīs: tibi quandō esse coepit?”

“He was a bad citizen.” “Yes, he was to others: when did he begin to be (so) to you?”

Exercises 3-6

3. Nē quicquam temerē ēgeritis! “The adverb temerē means ‘rashly’.”

4. Ille clāmāvit tantā vōce ut nōs procul ā forō sitī audīverimus.

5. Quīdam fuērint sēcūrī; fuēruntne cēterī?

6. Nunc videō quid ēgerim, et mē paenitet.

Distinguishing the Perfect Subjunctive and Future Perfect Active

These forms, the perfect subjunctive and future perfect active, look very similar to each other, I observed.

“Yes, the active forms of the perfect subjunctive and of the future perfect indicative are spelled the same, except in the first-person singular – amāverō (fut. perf. ind.), amāverim (perf. subj.).”

How do you decide which is which?

“The perfect subjunctive is more common: it should be your default choice. The future perfect is typically found in sentences with other future verbs, like Trimalchio’s harsh rule for his slaves that you encountered when reading Petronius:”

Quisquis servus sine dominicō iussū forās exierit accipiet plāgās centum.

Any slave who will have gone out without the master’s order will receive a hundred lashes.

accipiet is future tense and exierit is future perfect tense

The Future Perfect of Defective Verbs

“The future perfect also serves as the future tense for defective verbs like meminī and odī, as well as nōvī (perfect of nōscō), whose perfect forms have present meanings:”

Synopsis of Perfect System Tenses: meminī, ōdī, nōvī

| Perf. | meminī | I remember | ōdī | I hate | novī | I know |

| Plupf. | memineram | I remembered | ōderam | I hated | nōveram | I knew |

| Fut. Pf. | meminerō | I will remember | ōderō | I will hate | nōverō | I will know |

Synopsis of the Perfect System

“Here is a synopsis of tense forms in the perfect system for a regular verb:”

Synopsis of trahō, trahere, traxī, tractus, ‘to draw; drag’ Perfect System, First-Person Singular, Feminine

Indicative

| Active | Passive | Active | Passive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perf. | traxī | tracta sum | I drew; I have drawn | I was drawn; I have been drawn |

| Plupf. | traxeram | tracta eram | I had drawn | I had been drawn |

| Fut. Pf. | traxerō | tracta erō | I will have drawn | I will have been drawn |

Subjunctive

| Active | Passive | |

|---|---|---|

| Perf. | traxerim | tracta sim |

| Plupf. | traxissem | tracta essem |

“And here is a synopsis of tense forms in the perfect system for irregular sum:”

Synopsis of sum, esse, fuī, futūrus ‘to be’ Perfect System, Third-Person Plural

Indicative

| Perf. | fuērunt/ēre | they were; they have been |

| Plupf. | fuerant | they had been |

| Fut. Pf. | fuerint | they will have been |

Subjunctive

| Perf. | fuerint |

| Plupf. | fuissent |

Drill

Write a full synopsis (all tenses, both indicative and subjunctive, plus the imperatives, participles, and infinitives) of probō, probāre, probāvī, probātus in the third-person singular, masculine.

Conditional Sentences

“Now let us review a kind of sentence you have already encountered. Sentences that contain a clause beginning with sī or nisi, ‘if’ or ‘unless/if… not’, are called conditional sentences. A conditional sentence consists of two clauses: the clause introduced by sī or nisi is called the conditional clause or if-clause; what remains is the main clause or then-clause. There are four basic rules for conditionals.”

Indicative Verbs in Conditional Sentences

“First, when both clauses of a conditional sentence contain indicative verb forms, there are no special translation rules, except that a future or future perfect verb in the conditional clause may be translated as a present tense.”

Indicative Verbs in Conditional Sentences: Examples

Sī mē rogābis, sīc dīcam.

If you [will] ask me, I will speak thus.

rogābis and dīcam are future indicative; rogābis may be translated as future or present tense

Sī tē colō, Sexte, nōn amābō.

If I worship you, Sextus, I will not love (you).

colō is present indicative and amābō is future indicative

Sī ille vēnerit, laetī erimus.

If that man will have come / comes, we will be happy.

vēnerit is future perfect indicative and erimus is future indicative; vēnerit may be translated as future perfect or present tense

Exercises 7-9

7. Sī mē rogābis, sīc dīcam: vīnea est prīma. “A vīnea, -ae, f. is a ‘vineyard’.”

8. Sī campum istum trānsierimus, quid vidēbimus?

9. Sī līberī canunt vel lūdunt, laetī sunt.

Present or Perfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences

“Second, when a conditional sentence contains the present or perfect subjunctive in the conditional clause, translate it either as a present indicative or ‘were to verb’. When a conditonal sentence has the present subjunctive in the main clause, translate it ‘would verb’.”

Present or Perfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences: Examples

Sī fortiter pugnet, hostem vincat.

If he fights / were to fight bravely, he would conquer the enemy.

pugnet (conditional clause) is present subjunctive; vincat (main clause) is present subjunctive; pugnet may be translated like a present indicative or ‘were to verb’; vincat is translated ‘would verb’

Sī virtūtem ex mē discat, bonus vir fīat.

If he learns / were to learn virtue from me, he would become a good man.

discat (conditional clause) is present subjunctive; fīat (main clause) is present subjunctive; discat may be translated like a present indicative or ‘were to verb’; fīat is translated ‘would verb’

Sī longa aetās auctōritātem religiōnibus faciat, servanda est tot saeculīs fidēs.

If a long period of time creates / were to create authority for religions, then trust must be preserved for so many centuries.

faciat (conditional clause) is present subjunctive; servanda est (main clause) is present indicative (gerundive verb); faciat may be translated like a present indicative or ‘were to verb.’

Exercises 10-13

10. Sī quis deus mihi hoc beneficium det, fēlīx sim.

11. Sī tē dē mē interrogent, tacē et nōlī dīcere.

12. Etiam sī hostēs fugiant, cavendum est nē in perīcula cadāmus.

13. Principēs sibi minimam laudem parant nisi hostēs in proeliō vincant.

Imperfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences

“Third, when a conditional sentence contains an imperfect subjunctive in both the conditional clause and in the main clause, translate the conditional clause verb ‘were verbing’ and the main clause verb ‘would verb’.”

Imperfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences: Examples

Sī fortiter pugnāret, hostem vinceret.

If he were fighting bravely, he would conquer the enemy.

pugnāret (conditional clause) is imperfect subjunctive; vinceret (main clause) is imperfect subjunctive; pugnāret is translated ‘were verbing’; vinceret is translated ‘would verb’

Sī virtūtem ex mē disceret, bonus vir fieret.

If he were learning virtue from me, he would become a good man.

disceret (conditional clause) is imperfect subjunctive; fieret (main clause) is imperfect subjunctive; disceret is translated ‘were verbing’; fieret is translated ‘would verb.’

Exercises 14-16

14. Sī vīveret, verba eius audīrētis.

15. Sī hic cursus pateret, nōbīs prōdesset.

16. Sī vītam silentiō trānsīrēmus, essēmus velutī pecora.

Pluperfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences

“Fourth, when a conditional sentence contains a pluperfect subjunctive in both the conditional clause and in the main clause, translate the conditional clause verb like the pluperfect indicative and the main clause verb ‘would have verbed’.”

Pluperfect Subjunctive Verbs in Conditional Sentences: Examples

Sī fortiter pugnāvisset, hostem vīcisset.

If he had fought bravely, he would have conquered the enemy.

pugnāvisset (conditional clause) is pluperfect subjunctive; vīcisset (main clause) is pluperfect subjunctive; pugnāvisset is translated like the pluperfect indicative; vinceret is translated ‘would have verbed’

Sī virtūtem ex mē didicisset, bonus vir factus esset.

If he had learned virtue from me, he would have become a good man.

didicisset (conditional clause) is pluperfect subjunctive; factus esset (main clause) is pluperfect subjunctive; didicisset is translated like the pluperfect indicative; factus esset is translated ‘would have verbed.’

Exercises 17-19

17. Nisi tū istud āmīsissēs, numquam recēpissem.

18. Traxissēmus nāvēm ad lītus, sī licuisset et vōs ita cēnsissētis.

19. Nisi impetum in latus hostium gladiīs fēcissent, statim interissent.

When I finished these sentences, I saw an old man leave the cave and head out into the wild.

“He’s going out to pray. Every morning he begins translating before sunrise, and just before noon he goes out to pray.”

What is he translating?

“He is translating the Jewish holy books, as well as the holy books of the Christians, into Latin. He came to Jerusalem, among other reasons, so he could have access to the very best and most accurate manuscripts. Jerome has had to master Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. His translation will become the standard in Europe for the next thousand years so; in your day it is called the Vulgate.”

We got up and walked to Jerome’s cave. It was pleasantly cool inside and not damp at all – a good thing for books, of which there were many piled up on little tables. Latinitas showed me the manuscript Jerome was working on. But before she took me through it, she drilled me on some new vocabulary words:

Vocabulary

A-Verb (First Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| iūdicō, iūdicāre, iūdicāvī, iūdicātus | to judge |

E-Verbs (Second Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| audeō, audēre, ausus sum | to dare; be bold “This verb is a semi-deponent: it is deponent in the perfect system.” |

| gaudeō, gaudēre, gāvīsus sum | to be glad; rejoice in “This verb is a semi-deponent: it is deponent in the perfect system.” |

| respondeō, respondēre, respondī, respōnsus | to respond; answer |

I-Verbs (Third Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| cognōscō, cognōscere, cognōvī, cognitus | to understand; learn; know |

| crēdō, crēdere, crēdidī, crēditus | to believe; trust |

Mixed I-Verb (Third Conjugation -iō)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| perficiō, perficere, perfēcī, perfectus | to complete, perfect |

Irregular Verb

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| absum, abesse, āfuī, āfutūrus | to be away from; be absent |

Third Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| aes, aeris | n. | bronze |

| cinis, cineris | m. | ash |

| mōns, montis | m. | mountain; hill |

| scelus, sceleris | n. | crime; sin |

US-A-UM Adjective (First and Second Declension Adjective)

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| iūstus, -a, -um | just |

Conjunctions

| Latin Conjunction | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| -ve | or “Added to the end of the second word of a pair, like -que” |

| sīve / seu | or; whether |

Adverbs

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| ibi | there |

| inde | from there; from then |

| semel | once; a single time |

| simul | together; at the same time |

Exercises 20-26

20. Iūstum est cinerēs parentum colere.

21. Haud longē ā monte absumus; currāmus igitur nōs simul animō gaudente.

22. Inde furor quīdam eōs ad scelus perficiendum ēgit.

23. Ita mihi respondere ausus est: ‘crēde mihi, quod semel dīxī, haud mūtābō’.

24. Illō locō libentissimē ūtor, sīve quid mēcum ipse cōgitō, sīve quid aut scrībō aut legō.

25. Prior aeris erat quam ferrī cognitus ūsus. “According to Lucretius.”

26. Iūdicētur nōn verbō sed rē, nōn modo nōn cōnsul, sed etiam hostis Antōnius. “From Cicero’s Philippics; Antony is the subject.”

Jerome and the Vulgate Bible

She then showed me two passages from the manuscript, written in Jerome’s own hand, which was small but neat and legible. One was from the book of Genesis, and described a conversation between Abraham and the supreme deity regarding the fate of the city of Sodom.

Jerome, Vulgate Bible, Book of Genesis Excerpt

1) Convertēruntque sē inde, et abiērunt Sodomam; Abraham vērō adhūc stābat cōram Dominō.

convertō, convertere, convertī, conversus ~ vertō, vertere, vertī, versus

Sodomam ‘to Sodom’ (city famous for its wickedness)

cōram + abl. face to face with

2) Et appropinquāns ait: numquid perdēs iūstum cum impiō? Sī fuerint quīnquāgintā iūstī in cīvitāte, perībunt simul? Et nōn parcēs locō illī propter quīnquāgintā iūstōs, sī fuerint in eō? Absit ā tē ut rem hanc faciās, et occīdās iūstum cum impiō, fīatque iūstus sīcut impius, nōn est hoc tuum: quī iūdicās omnem terram, nēquāquam faciēs iūdicium hoc.

appropinquō, appropinquāre, appropinquāvī, appropinquātus to approach

impius, -a, -um impious; disloyal

quīnquāgintā fifty

propter + acc. because of; for the sake of

iūdicō, iūdicāre, iūdicāvī, iūdicātus to judge

nēquāquam in no way

3) Dīxitque Dominus ad eum: Sī invēnerō Sodomīs quīnquāgintā iūstōs in mediō cīvitātis, dīmittam omnī locō propter eōs.

Sodomīs ‘in Sodom’

dīmittō, dīmittere, dīmīsī, dīmissus (here, + dat.) to spare

4) Respondēnsque Abraham, ait: quia semel coepī, loquar ad Dominum meum, cum sim pulvis et cinis. Quid sī minus quīnquāgintā iūstīs quīnque fuerint? Dēlēbis, propter quadrāgintā quīnque, ūniversam urbem? Et ait: nōn dēlēbō, sī invēnerō ibi quadrāgintā quīnque.

pulvis, pulveris, m. dust

minus quīnquāgintā iūstīs ‘less than fifty just men’ (ablative of comparison)

dēleō, dēlēre, dēlēvī, dēlētus to destroy

ūniversus, a, um all; the entire

5) Rūrsumque locūtus est ad eum: sīn autem quadrāgintā ibi inventī fuerint, quid faciēs? Ait: nōn percutiam propter quadrāgintā.

rūrsum = rūrsus, again

sīn but if

percutiō, percutere, percussī, percussus to shatter; destroy

6) Nē quaesō, inquit, indignēris, Domine, sī loquar: quid sī ibi inventī fuerint trīgintā? Respondit: nōn faciam, sī invēnerō ibi trīgintā.

quaesō ‘I beg’ (other forms of this verb are rare)

indignor, indignārī, indignātus sum to be offended; be indignant

7) Quia semel, ait, coepī, loquar ad Dominum meum: quid sī ibi inventī fuerint vīgintī? Ait: nōn interficiam propter vīgintī.

interficiō, interficere, interfēcī, interfectus to kill

8) Obsecrō, inquit, nē īrāscāris, Domine, sī loquar adhūc semel: quid sī inventī fuerint ibi decem? Et dīxit: nōn dēlēbō propter decem.

obsecrō, obsecrāre, obsecrāvī, obsecrātus to implore

īrāscor, īrāscārī, īrātus sum to be angry

adhūc semel ‘once more’

9) Abiitque Dominus, postquam cessāvit loquī ad Abraham; et ille reversus est in locum suum.

cessō, cessāre, cessāvī, cessātus to cease

revertor, revertī, reversus sum to return

When we finished, she turned to another passage, one from Paul of Tarsus’ first letter to the people of Corinth. I had heard this one recited at weddings before.

Jerome, Vulgate Bible, First Book of Corinthians Excerpt

1) Sī linguīs hominum loquar, et angelōrum, cāritātem autem nōn habeam, factus sum velut aes sonāns, aut cymbalum tinniēns. Et sī habuerō prophētīam, et nōverim mystēria omnia, et omnem scientiam: et sī habuerō omnem fidem ita ut montēs trānsferam, cāritātem autem nōn habuerō, nihil sum. Et sī distribuerō in cibōs pauperum omnēs facultātēs meās, et sī trādiderō corpus meum ita ut ārdeam, cāritātem autem nōn habuerō, nihil mihi prōdest.

angelus, -ī, m. angel; messenger

cāritās, cāritātis, f. love (in the sense of valuing someone)

sonō, sonāre, sonāvī, sonātus to sound; echo

cymbalum, -ī, n. cymbal

tinniō, tinnīre, tinnīvī tinnītus to ring

prophētīa, -ae, f. prophecy

mystērium, -ī, n. mystery (religious secret)

scientia, -ae, f. knowledge

trānsferō, trānsferre, trānstulī, trānslātus to transfer; move to another place

distribuō, distribuere, distribuī, distribūtus to distribute

pauper, pauperis poor

facultās, facultātis, f. resource

2) Cāritās patiēns est, benigna est. Cāritās nōn aemulātur, nōn agit perperam, nōn īnflātur, nōn est ambitiōsa, nōn quaerit quae sua sunt, nōn irrītātur, nōn cōgitat malum, nōn gaudet super inīquitāte, congaudet autem vēritātī: omnia suffert, omnia crēdit, omnia spērat, omnia sustinet. Cāritās numquam excidit, sīve prophētīae ēvacuābuntur, sīve linguae cessābunt, sīve scientia dēstruētur.

benignus, -a, -um generous

aemulor, aemulārī, aemulātus sum to be competitive; be jealous

perperam rashly; thoughtlessly

īnflō, īnflāre, īnflāvī, īnflātus to inflate; fill with air

ambitiōsus, -a, -um solicitious

irrītō, irrītāre, irrītāvī, irrītātus to irritate

inīquitās, inīquitātis, f. iniquity; injustice; evil

congaudeō, congaudēre the prefix con- adds ‘together with’ to the verb’s meaning

vēritās, vēritātis, f. truth

sufferō, sufferre, sustulī, sublātus to endure; suffer

excidō, excidere, excidī, excisus to fade away

ēvacuō, ēvacuāre, ēvacuāvī, ēvacuātus to make empty; render void; cancel

dēstruō, dēstruere, dēstruxī, dēstructus to destroy

3) Ex parte enim cognōscimus, et ex parte prophētāmus. Cum autem vēnerit quod perfectum est, ēvacuābitur quod ex parte est. Cum essem parvulus, loquēbar ut parvulus, cōgitābam ut parvulus. Quandō autem factus sum vir, ēvacuāvī quae erant parvulī.

ex parte in a partial way

prophētō, prophētāre, – , prophētātus to foretell; prophesy

parvulus, -a, -um very small; young

quae erant parvulī ‘things which were (characteristic) of a small boy’

4) Vidēmus nunc per speculum in aenigmate: tunc autem faciē ad faciem. Nunc cognōscō ex parte: tunc autem cognōscam sīcut et cognitus sum. Nunc autem manent fidēs, spēs, cāritās, tria haec: maior autem hōrum est cāritās.

speculum, -ī, n. mirror

aenigma, aenigmatis, n. riddle; something obscure

When we were done, I carefully restored Jerome’s manuscript to the table on which we found it. Not for the first time, I felt as if I was in a museum, one where I had the privilege of handling the objects, provided that I treated them with care and respect.

As we left, it occurred to me that Latinitas might be feeling out of place in this world, the world of Christiandom and late antiquity. She was, after all, a goddess, and there was no room for goddesses in a Christian world – all the traditional gods, like Jupiter, Juno, Mars, and Ceres, were seen by Christian theologians as daemonēs, powerful spirits operating under the direction of Satan. I did not think there was anything satanic about Latinitas, but I wondered whether she felt uncomfortable visiting thinkers who might have seen her as a force for evil.

Because she was something like a goddess, Latinitas read my mind.

“I’m always perfectly at home and perfectly comfortable wherever we go. You might call me a goddess, but that’s a rather simplistic way of looking at things. The world contains gods, it contains humans and animals, it contains plants and fungi and protists, but that’s just the beginning of the list. There are beings and forces in the world that are just as alive as all these but that you mortals forget about sometimes. It’s not an easy thing to explain; but tomorrow, when we go on our last adventure, I will provide you with some lasting food for thought.”

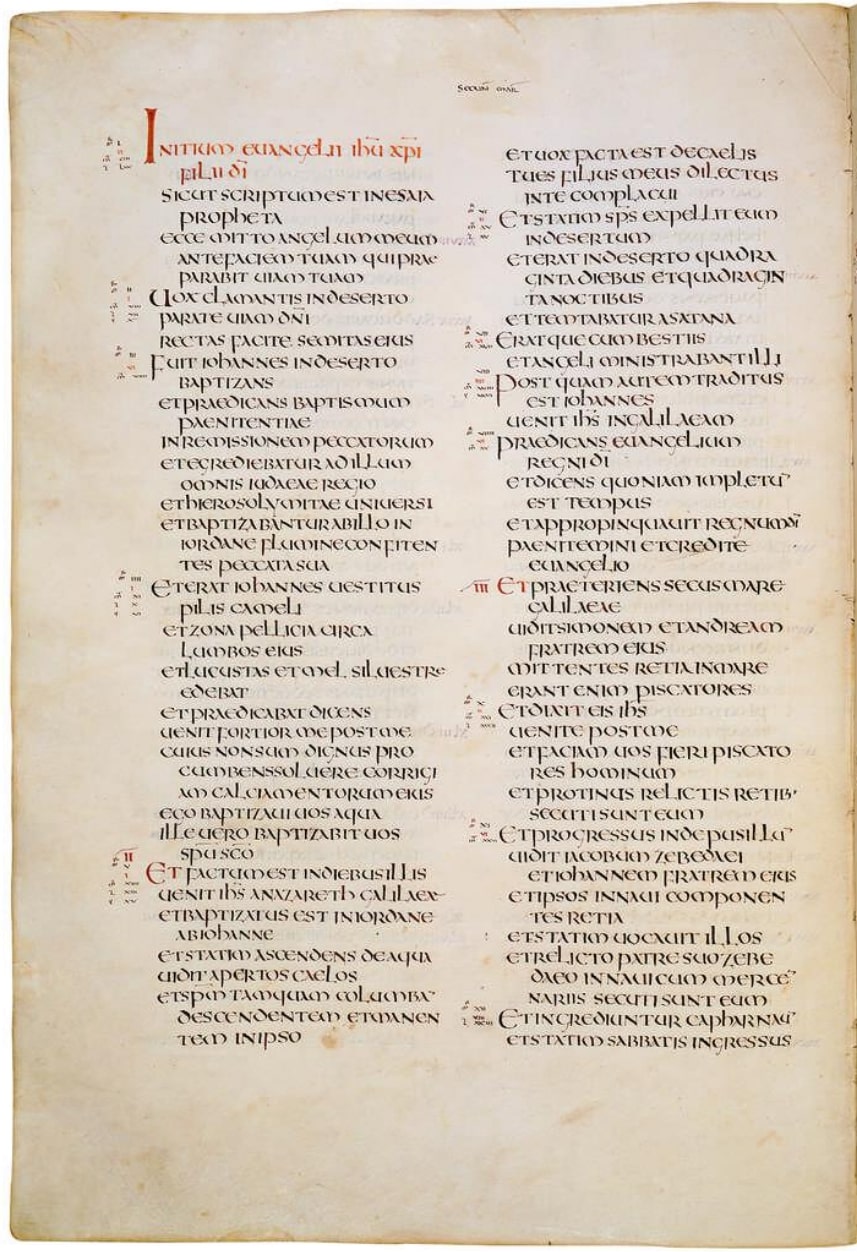

77. Text of Jerome’s translation of the Gospel of Mark, from the Codex Amiatinus, created in 700 CE. Haec est veterrima ēditiō Bibliae Latīnae quae nōbīs trādita est integra. This is the most ancient edition of the Latin Bible which has come down to us complete. It was copied in a monastery in northeast England; monasteries there and in Ireland played a critical role in transmitting earlier Latin literature.