63. An ivory carving, the ‘Lakshmi statuette’, manufactured in India but found in Pompeii. How it traveled so far from its native land is unknown. Īgnōtum est quōmodo tam procul ā patriā ferrētur.

Explōrātiō Vīcēnsima Nōna (XXIX) Adventure Twenty-Nine

Use of the Gerundive as a Verbal Adjective

Use of the Gerundive as a Verb Expressing Obligation

Dative of Agent with Gerundive Verb Expressing Obligation

Impersonal Gerundive Verb Expressing Obligation

Uses of the Gerund and Further Uses of the Gerundive

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Genitive

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Dative

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Accusative

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Ablative

Apuleius’ Flōrida: The Marvels of India

Where and When Are We Today?

Forum, Carthāgō

Mēnsis Mārtius

M. Gāviō Orfitō L. Arriō Pudente cōnsulibus

The Forum, Carthage

March, 165 CE

As soon as we blinked into the past this time, Latinitas asked me to guess which city we were in. Before us, underneath a large-framed tent, was a little urban market, with merchants at their stalls selling various items – lamps, bowls, statues, flowers, fruit – along with many different kinds of spice. The scent of the spices, the workmanship of the carvings, and the dress of the vendors immediately made me think of India, so I guessed India.

“The correct answer is Carthage,” she said, “the same city we visited a few weeks ago. You can tell from the street painting,” – she pointed behind me to a large graffito in slanting letters that read BENE CACĀ, ‘shit well!’ – “that we are in a place where people speak Latin. India is not part of the Roman Empire, but the Empire’s trade routes extend far beyond its borders – westward along the Atlantic coast, and east, into the Indian Ocean. There is a thriving trade, particularly in the cities, for imports from the Arabian peninsula and India, with the biggest demand for spices and scents that do not grow in the Mediterranean. This cinnamon, this pepper, these ivory statues – all come from India. And where there is trade and travel, immigrants follow; this is Carthage’s Indian neighborhood. It’s not as large as the ones in Rome and Alexandria, but it is still growing.”

I walked over to one of the stalls and saw a sign that said PIPER on a basket of peppercorns. I verified the meaning of the word with Latinitas and asked her for some coins.

Ego volō aliquid piperis, ‘I want some pepper’, I said to the mercātrix.

Tribus assibus, three as’s (the smallest coin), she replied, and gave me a few ounces worth wrapped in a piece of cloth. I planned to give this to my family, who for a while had been wondering why I would not answer my phone in the afternoon. They would never believe my story if I told them, of course, but I thought gifting them some genuine 1,900 year-old black pepper would be a nice gesture.

Apuleius

The last time we visited Carthage, in the era of Julius Caesar and Sallust, the city was still a bit of a ghost town. This time crowds stretched down the street as far as the eye could see. As we walked to the forum or city center a wagon passed us carrying a large statue of Juno, gorgeously decorated with flowers and colorful cloth. The Carthaginian forum was like flatter version of the Roman one, and even had its own version of the temple of Capitoline Jupiter. Most of the people were chatting in Latin, but there were languages I didn’t recognize too, one that Latinitas called Punic – a branch of the Semitic languages related to Phoenician, a distant cousin of Arabic and Hebrew – and one she called Berber, an old African language.

We found a place to study behind the Capitoline temple, and Latinitas handed me a green pear she had bought at the market, which I snacked on while watching the crowd. From where we sat we could see a speakers’ platform, rostra, and a man who was preparing to make a speech to the crowd gathered below. He was a middle-aged man, charismatic and tall, and I noticed that his leg was bandaged and splinted. He was clearly recovering from some kind of leg injury, and he was leaning heavily on his staff.

“Ille est Āpulēius – Lūcius Āpulēius Madaurēnsis. That’s Lucius Apuleius, a native of the city of Madaurus, which is about a hundred miles west of here, near the edge of the Sahara Desert. We are going to listen to him speak later.”

Gerundives

“First, though, take out your book. I want to teach you about the gerundive and gerund today. The gerundive is a verbal adjective (sometimes called the future passive participle). It is formed with the present stem of the verb with the usual connecting vowel(s) for each conjugation, plus -nd-, followed by US-A-UM (first and second declension) endings:”

Formation of the Gerundive

| Conjugation | Present Stem + Vowel(s) | Gerundive Ending | Gerundive Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| A-Verb (1st) | ama- | -ndus, -a, -um | amandus, -a, -um |

| E-Verb (2nd) | move- | -ndus, -a, -um | movendus, -a, -um |

| I-Verb (3rd) | dīce- | -ndus, -a, -um | dīcendus, -a, -um |

| Long I-Verb (4th) | audie- | -ndus, -a, -um | audiendus, -a, -um |

| Mixed I-Verb (3rd -iō) | capie- | -ndus, -a, -um | capiendus, -a, -um |

Use of the Gerundive as a Verbal Adjective

“The basic meaning of the gerundive is ‘to be verbed’. It is passive and refers to the future, but it often implies obligation. For example, the English word ‘agenda’ is the neuter plural gerundive agenda from the verb agō, agere, and it means ‘(things) to be done’. Here are two more examples:”

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Relīquimus illīc eum servandum. | We left him there to be saved. |

| Agenda meminimus. | We remember (the things) to be done. |

Use of the Gerundive as a Verb Expressing Obligation

“The gerundive is also used as part of a verb form that expresses obligation or necessity: amandus sum literally means ‘I am to be loved’, but the idea is one of obligation, so a better translation would be ‘I ought to be loved’ or ‘I must be loved’. The gerundive verb expressing obligation consists of a nominative form of the gerundive plus a form of the verb sum, esse in any tense:”

Gerundive Verb, Present Tense Example

| Gerundive Verb Form | English Translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| amandus, -a, -um sum | amandī, -ae, -a sumus | I must be loved | we must be loved |

| amandus, -a, -um es | amandī, -ae, -a estis | you must be loved | you all must be loved |

| amandus, -a, -um est | amandī, -ae, -a sunt | he, she, it must be loved | they must be loved |

Gerundive Verb Examples

Omnia paranda sunt sī bellum incipere vultis.

Everything must be prepared if you all want to begin the war.

Invīsus nātālis adest, quī rūre molestō

et sine Cērinthō trīstis agendus erit.

A hateful birthday is here, which, in the annoying countryside,

and without Cerinthus, will need to be spent depressed.

“The gerundive verb can also be an infinitive, in which case the gerundive is in the accusative form, just as you saw with the perfect passive and future active infinitive:”

Dīxit pācem petendam esse, virōs līberandōs esse.

He said that peace needed to be sought, that the men needed to be freed.

Dative of Agent with Gerundive Verb Expressing Obligation

“The person who has the obligation to do the action of a gerundive verb goes in the dative case, not the ablative. Such a dative noun or pronoun should be translated with the word ‘by’:”

Omnia mihi paranda sunt sī bellum incipere vultis.

Everything must be prepared by me if you all want to begin the war.

Exercises 1-8

1. Mediā nocte dē agendīs dīcēbāmus.

2. Hic error mihi tollendus est.

3. Faciendum est nōbīs id quod parentēs iubent.

4. Nōnne amābis ea quae amanda tibi sunt?

5. Haec difficilia patior et ferenda esse prō rē pūblicā putō.

6. Hodiē multa nōbīs facienda sunt: librī legendī sunt, cibus parandus est, līberī hortandī sunt.

7. Ō cīvēs, haec verba mea vōbīs rūrsus audienda sunt: Carthāgō dēlenda est.

“The verb dēleō, dēlēre, dēlēvī, dēlētus means ‘to destory’, and the name is Carthāgō, Carthāginis, f.”

8. All the gods must be worshipped (are to be worshipped) by us.

Impersonal Gerundive Verb Expressing Obligation

“The gerundive verb can also be used impersonally, to say that ‘one ought to’ or ‘one must’ do the action of the verb. The impersonal gerundive verb is formed with the neuter nominative singular gerundive adjective, plus a third-person singular form of sum in any tense:”

Impersonal Gerundive Verb Examples

| Impersonal Gerundive Verb Form | English Translation |

|---|---|

| audiendum est | one ought to listen |

| pārendum erit | one will need to obey |

| dormiendum est | one must sleep |

Exercises 9-11

9. Pārendum est tibi: quod iubēs, colēris.

10. Studendum est librīs, ōrātiōnibus atque carminibus.

11. Nūllī labōrī, nūllīs opibus parcendum erit.

Gerunds

“Now to gerunds. The gerund is a verbal noun, which can be translated ‘verbing’. In the English sentence ‘I love reading’, ‘reading’ is a gerund that serves as the direct object of the sentence. The Latin gerund is formed from the neuter singular of the gerundive, but it only occurs in the genitive, dative, accusative, and ablative – never in the nominative form. For example, the gerund forms of amō, amāre are amandī, amandō, amandum, amandō.”

Uses of the Gerund and Further Uses of the Gerundive

“In Latin, the gerund can be used in many of the same ways that any noun is used, but we will focus on the most common ones. In general, the Latin gerund does not take an object. In English, one can say ‘I love reading books’, with ‘books’ as object of the gerund ‘reading’, but you tend not to do so in Latin. If you want to express an object, you instead use the gerundive adjective, in agreement with what you wanted to make the object of the gerund. Let’s go case-by-case to illustrate.”

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Genitive

“A gerund in the genitive works much like any other genitive: it depends on another word in the sentence. A common use is with the ablative singular noun forms grātiā and causā, both meaning ‘for the sake of’, which work like a preposition except that they come after the genitive form.”

Vocabulary

Prepositions

| Latin Preposition + Case | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| causā + gen. | for the sake of “This ‘preposition’ usually follows the genitive word.” |

| grātiā + gen. | for the sake of “This ‘preposition’ usually follows the genitive word.” |

Genitive Gerund (and Gerundive) Examples

| Gerund | Gerundive |

|---|---|

| ars exercendī | ars mīlitum exercendōrum |

| the art of training | the art of training soldiers |

| servandī causā / grātiā | urbis servandae causā / grātiā |

| for the sake of saving | for the sake of saving the city |

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Dative

“A gerund in the dative generally expresses purpose. You can translate it ‘for (the purpose of) verbing’, or simply ‘to verb’:”

Dative Gerund (and Gerundive) Example

| Gerund | Gerundive |

|---|---|

| diēs colendō | diēs agrīs colendīs |

| a day for (the purpose of) cultivating | a day for (the purpose of) cultivating fields; to cultivate fields |

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Accusative

“A gerund in the accusative occurs with the prepostion ad, and it expresses purpose. You can translate it ‘for (the purpose of) verbing’, or simply ‘to verb’:”

Accusative Gerund (and Gerundive) Example

| Gerund | Gerundive |

|---|---|

| domum mē recēpī ad scrībendum | domum mē recēpī ad litterās scrībendās |

| I went home for (the purpose of) writing; to write | I went home for (the purpose of) writing a letter; to write a letter |

The Gerund (and Gerundive) in the Ablative

“A gerund in the ablative works much like any other ablative: for example, it can depend on a preposition, or it can express means, in which case you should translate it ‘by verbing’.”

Ablative Gerund (and Gerundive) Examples

| Gerund | Gerundive |

|---|---|

| petendō | petendīs honōribus |

| by seeking | by seeking honors |

| exercitātus in dīcendō | exercitātus in hīs dīcendīs |

| practiced in speaking | practiced in saying these (things) |

Exercises 12-17

12. Amōrem quaeris amandō.

13. Rōmae videndae causā vēnimus.

14. Petendā pāce, vītam līberīs relīquimus meliōrem.

15. Ad hostēs pugnandōs castra nōn longē ab eō oppidō posuērunt.

16. Magis dandīs quam accipiendīs beneficiīs amīcitiās parābant.

17. Hīc ego sī fīnem dīcendī nōn faciam, vōs omnēs audīre nōlētis.

“Now let’s learn some new vocabulary, which we will hear when we listen to Apuleius.”

Vocabulary

Long I-Verb (Fourth Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| conveniō, convenīre, convēnī, conventus | to come together |

First Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| mēnsa, mēnsae | f. | meal; table |

| sapientia, sapientiae | f. | wisdom |

Second Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| proelium, proeliī | n. | battle |

Third Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| amnis, amnis “I-stem.” | m. | river |

| arbor, arboris | f. | tree |

| color, colōris | m. | color |

| genus, generis | n. | type; kind |

| senex, senis | m. | old man |

US-A-UM Adjectives (First and Second Declension Adjectives)

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| aequus, -a, -um | fair; equal |

| cēterus, -a, -um | other; the rest |

| situs, -a, -um | situated; facing |

Third Declension Adjectives

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| dīves, dīvitis | rich |

| immānis, immāne | enormous |

Preposition

| Latin Preposition + Case | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| apud + acc. | at the place of; among |

Adverb

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| praetereā | furthermore |

| procul | far |

Exercises 18-23

18. Cicerō sapientiam artem vīvendī putandam esse dīxit.

19. Rōmānī in hōc proeliō superiōrēs erant, quod omnēs hostium cōpiae ūnō in locō convēnerant.

20. Īris variōs colōres per caelum fert sōle sub ārdentī.

“Īris is the goddess of the rainbow.”

21. Senem, in quō est adulēscentis aliquid, probō.

“The verb probō, probāre, probāvī, probātus means ‘to approve (of)’.”

22. Quem dūcimus dīvitem? In quō homine hoc verbum pōnimus? Estne quī plūrima aurea habet? Quī maximam mēnsam? Aut quī satis habet ad bene vīvendum?

23. Nōs praetereā, sitī procul ā patriā, apud aliēnōs, intellegimus nōmina nōbīs nunc danda esse; omnia nova – arborēs, amnēs immānēs, et aequē cūncta genera animālium – appellanda sunt.

Apuleius’ Flōrida

Apuleius is best known today as the author of a long Latin novel, the Metamorphōsēs, which is also known as the Asinus Aureus, The Golden Ass. It tells the story of a man named Lucius who was magically transformed into a donkey after witnessing certain secret magic rites. At the end he is turned back into a human and converts to the worship of the goddess Isis.

But his fame as a novelist came later. His contemporaries in Carthage knew him as a sophist, a public speaker who could entertain and educate crowds with his lectures. He was about to launch into a long disquisition on foreign lands. The first place he talked about was India. I realized that I had seen him leaving the Indian market just when we arrived there. So India must have been on his mind.

Latinitas opened up a small blue book to the beginning of his speech so I could read it – the book contained fragments of his speeches, in a collection called Flōrida. The title either designates the work as an anthology or refers to Apuleius’ ‘florid’ style. I couldn’t understand him well in real time, but after he had spoken for a few minutes, we went over the text together. It started like this:

Apuleius’ Flōrida: The Marvels of India

1) “Translate this section using the vocabulary notes for help. Note that this is not a complete sentence (it lacks a verb):”

Indī, gēns populōsa cultōribus et fīnibus maxima, procul ā nōbīs ad orientem sitī, prope Ōceanī reflexūs et sōlis exortūs, prīmīs sīderibus, ultimīs terrīs, super Aegyptiōs ērudītōs et Iūdaeōs superstitiōsōs et Nabathaeōs mercātōrēs et fluxōs vestium Arsacidās et frūgum pauperēs Ityraeōs et odōrum dīvitēs Arabās –

Indus, -a, -um Indian

populōsus, -a, -um populous

cultor, cultōris, m. inhabitant

orientem: Understand ‘sōlem’ with the participle.

Ōceanī reflexūs ‘turning points of Ocean’

exortus, exortūs, m. rising

ultimus, -a, -um most distant

ērudītus, -a, -um learned; erudite

superstitiōsus, -a, -um intensely religious (referring to the inhabitants of the province of Judaea)

mercātor, mercātōris, m. merchant (referring to a tribe living in northwestern Arabia)

fluxōs vestium Arsacidās ‘Parthians with billowing clothes’

frūgum pauperēs Ityraeōs ‘Ityraei poor in grain’ (a people living in what is now Lebanon)

odor, odōris, m. scent

2) “Translate the next two sections using the vocabulary notes for help; some new vocabulary is not glossed, but try to work out the meaning:”

a) eōrum igitur Indōrum nōn aequē mīror eboris struēs et piperis messēs et cinnamī mercēs et ferrī temperācula et argentī metalla et aurī fluenta, nec quod Gangēs apud eōs ūnus omnium amnium maximus Eōīs rēgnātor aquīs in flūmina centum discurrit…

eboris struēs ‘piles of ivory’

piperis messēs ‘harvests of pepper’

merx, mercis, f. merchendise; commodity

temperāculum, -ī, n. smelting-furnace

metallum, -ī, n. mine

fluentum, -ī, n. stream

Eōīs rēgnātor aquīs ‘king among Eastern waters’

discurrit ‘divides’

b) nec quod īsdem Indīs ibīdem sitīs ad nāscentem diem tamen in corpore color noctis est, nec quod apud illōs immēnsī dracōnēs cum immānibus elephantīs pārī perīculō in mūtuam perniciem concertant… Sunt apud illōs et varia colentium genera.

ibīdem in the same place

dracō, dracōnis, m. serpent; dragon

perniciēs, perniciēī, f. destruction

concertō, concertāre, concertāvī, concertātus to struggle; fight

3) If you want, do this section as the following interactive exercise. or if you prefer, use the text version below.

3) Text version

“Identify the five gerundive adjective – noun pairs in this translated section:”

Sunt et mūtandīs mercibus callidī et obeundīs proeliīs strēnuī vel sagittīs ēminus vel ēnsibus comminus. Est praetereā genus apud illōs praestābile, Gymnosophistae vocantur. Hōs ego maximē admīror, quod hominēs sunt perītī nōn propāgandae vītis nec inoculandae arboris nec prōscindendī solī; nōn illī nōrunt arvum colere vel aurum cōlāre vel equum domāre vel taurum subigere vel ovem vel capram tondēre vel pāscere.

There are (men) skilled at trading merchandise and energetic at facing battles either with arrows, at a distance, or with swords, hand-to-hand. There is, furthermore, a race among them, an outstanding one, called the Gymnosophists (‘Naked Wise Men’). These men I especially admire, because they are persons skilled, not in propagating the vine nor grafting a tree nor cutting the soil; they don’t know how to cultivate a field or pan for gold or tame a horse or break a bull or to shear or feed a sheep or goat.”

4) “Translate this next section using the vocabulary notes below; some new vocabulary is not glossed, but try to work out the meaning:”

Quid igitur est? Ūnum prō hīs omnibus nōrunt: sapientiam percolunt tam magistrī senēs quam discipulī iūniōrēs. Nec quicquam aequē penes illōs laudō, quam quod torpōrem animī et ōtium ōdērunt. Igitur ubi mēnsā positā… omnēs adolēscentēs ex dīversīs locīs et officiīs ad dapem conveniunt; magistrī perrogant, quod factum ā lūcis ortū ad illud diēī bonum fēcerint.

nōrunt short for nō[vē]runt, from nōscō, nōscere, nōvī, nōtus

percolō, percolere, percoluī, percultus the prefix ‘per-’ adds ‘thoroughly’ to the verb’s meaning

penes + acc. at the place of; among

torpor, torpōris, m. sluggishness

daps, dapis, f. feast

fēcerint ‘they have done’ (perfect active subjunctive form)

illud ‘that point’

5) “Answer the questions below this concluding section, which is translated:”

Hic alius sē commemorat inter duōs arbitrum dēlēctum, sānātā simultāte, reconciliātā grātiā, pūrgātā suspīciōne, amīcōs ex īnfēnsīs reddidisse; itidem alius sēsē parentibus quaepiam imperantibus oboedisse, et alius aliquid meditātiōne suā repperisse vel alterīus dēmōnstrātiōne didicisse; dēnique cēterī commemorant. Quī nihil habet adferre cūr prandeat, inprānsus ad opus forās extrūditur.

This one mentions that he was selected as the arbitrator between two men, and when their grudge was healed, their goodwill restored, their suspicion cleansed, he rendered them friends instead of enemies; next, another one mentions that he obeyed his parents ordering something, and another, that he discovered something by his own meditation or learned from another man’s demonstration; then the others mention things. He who has nothing to bring forward (as a reason) why he should eat lunch, is driven out, without lunch, to do his work.

Questions

sē How translated?

reddidisse What form is this? How is it translated?

aliquid How translated?

alterīus Case and number?

ad opus How translated?

When his lecture was over, Apuleius was presented with a garland of flowers as the crowd cheered and a band began to play. As he limped away to the litter that he traveled in he raised his hands triumphantly. The statue of Juno was carried through the crowd, and people formed a procession behind it, dancing as they moved along. Everyone was having a good time and although I had to get home soon to take a phone call from my doctor, I didn’t want to leave.

“We’ll be coming back to Carthage again tomorrow,” Latinitas said before we left, “but it will be a more challenging visit, emotionally, so be prepared.”

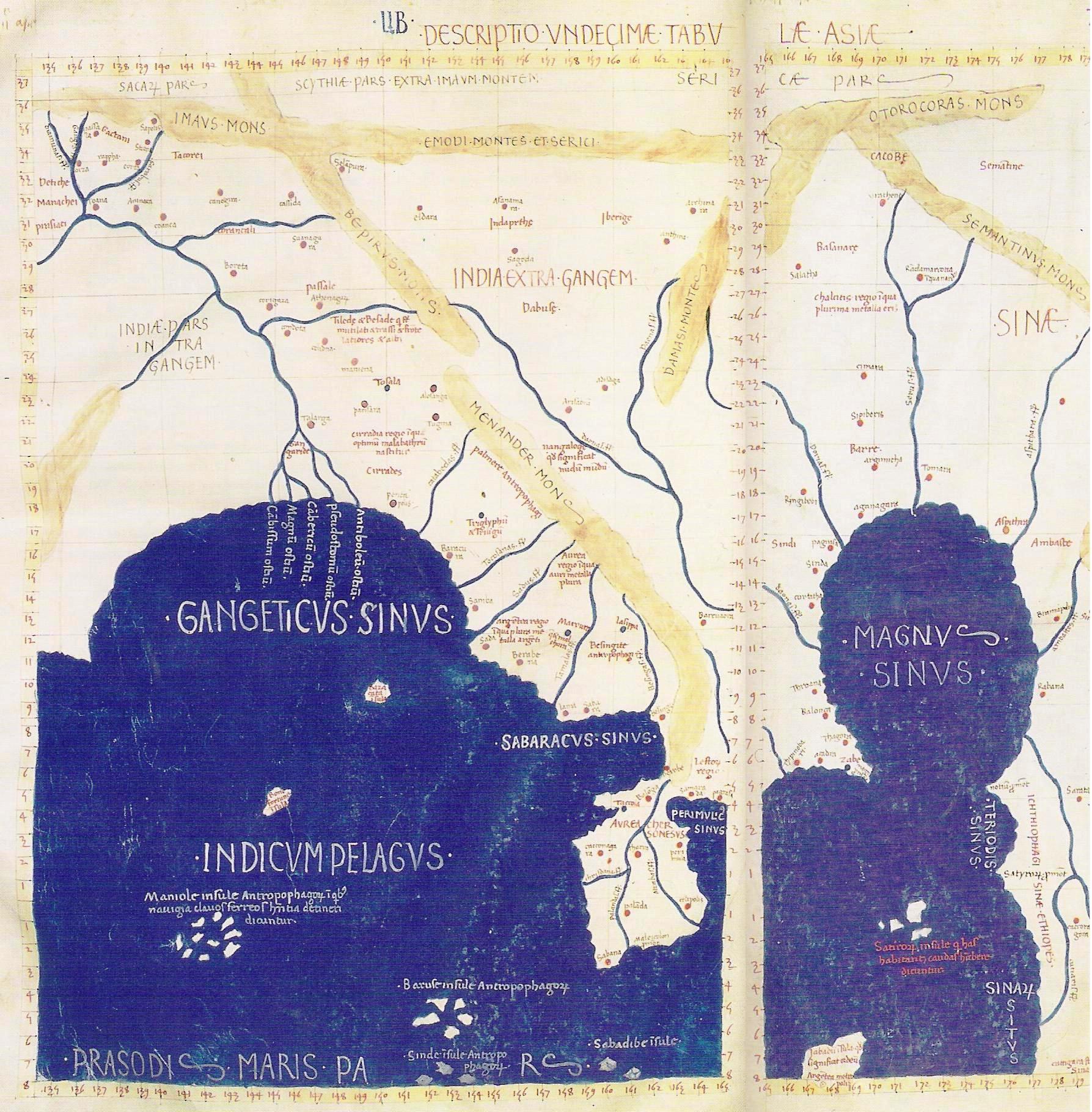

64. Maps from a Renaissance manuscript based on maps made in the 2nd century CE by Ptolemy of Alexandria, the astronomer. The upper map shows the world that Ptolemy knew, the lower map shows the mouth (ōra) of the Ganges river emptying into the bay (sinus) of the river and the Indian Sea (Indicum Pelagus).