61. Pavīmentum Pompēiīs ex domō Faunī quod fēlem, gallum, anatēs, aliquōs piscēs refert. A mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii which shows a cat, cock, ducks, and some fish.

Explōrātiō Vīcēnsima Octāva (XXVIII) Adventure Twenty-Eight

Perfect Passive and Future Active Infinitives

The Perfect Passive Infinitive

Accusative and Infinitive in Indirect Statement

Translating an Accusative Subject in Indirect Statement

Translating an Infinitive in Indirect Statement

Verb Tense in Indirect Statement

Translating an Infinitive in Indirect Statement, Continued

Marcus Aurelius’ Letter to Fronto

Where and When Are We Today?

Lōrium, Etrūria, Ītalia

Mēnsis Aprīlis

L. Cuspiō Pactumēiō Rufīnō L. Stātiō Quadrātō cōnsulibus

Lorium, in Etruria, Italia

April, 142 CE

Latinitas met me outside today, with a different greeting than usual. Havē, she said to me, hello. She explained this was a substitute for salvē, and so I replied havē in turn. She shook the rain off her umbrella and stuck it behind the bench.

“Today we are going to visit a Roman emperor again, and this time get a little closer. And after we’re done, if we have time, we’ll make a short stop somewhere more exotic.”

New Jersey?

“No, more exotic than that, you’ll see.”

The culīna or kitchen in front of us was giving off heat through its door. It had a high, smoke-covered ceiling, and while it was not huge – maybe the size of the kitchen at the pizza parlor around the corner from me – it clearly belonged to an important domus. Many of the pieces of serving-ware were silver, and there were two clay baking ovens along one wall, plus a fireplace for boiling things on the other, and a place to roast meats on a spit that could have easily accommodated a large boar – in fact, a fresh pair of tusks stood propped up against the wall. Latinitas, who had disguised herself as one of the servants, was standing near the entrance with me, waiting for the cooks to finish their work.

She was eventually given a basket of fine white crispy bread which she passed over to me. She took the hot dishes, two clay pots containing asparagus in a dark liquid that smelled somewhat like fish sauce, along with a roasted duck. We carried the meal down a long passageway, past dozens of little pantries and bedrooms. We saw no one in the hall, but from the other side of the complex – and I had begun to suspect we were in something like a palace – I could hear a large crowd of people making conversation, and the occasional note of a musical instrument. One servant – an older enslaved man who was talking to himself and seemed to be on the verge of a panic attack – came running through the corridor so fast that we barely pressed ourselves up against the wall in time. While we stopped, I ran my hand over the wall and contemplated its beautiful paint job, a soft, glossy mix of red and yellow panels with a fine decoration of black lines.

We eventually reached the room we were looking for. Cibus, ‘food’, Latinitas yelled, and a young man told us to come in: Intrāte. He did not pay me any attention. Hūc, ‘over here’, he said to Latinitas, pointing to a clear spot in his room, much of which was a mess of writing tablets and books. As we turned to leave, he stopped us – manēte – and reached for one of the documents. Hae ad Frontōnem. Hae referred to the litterae or letter he handed her. I could already tell that this was going to be our reading for today.

We walked to the end of the hallway and took a stairway to the second floor, then climbed a ladder up to a belvedere, a small open tower, which afforded us a good view of the palace, and a place to study and chat.

Who was room service for? I asked.

“That was young Mārcus Aurēlius. You can call him the emperor Marcus Aurelius, although he won’t receive that title for another twenty years, when he turns forty. His adopted father, Antoninus Pius, the current emperor, is raising him to be his heir.”

He didn’t look especially emperor-like to me – he could have been any of the thousands of young Italian men we had run across – but of course it’s not in your genetics to be one; it takes a long period of training and experience.

Across the courtyard I could see the dining room where a large party was gathered for dinner.

“Pius is over there with his family and courtiers.”

Why doesn’t Marcus Aurelius join them?

“Marcus has chosen to live the life of a philosopher – a Stoic philosopher in particular, the same school that Seneca and Musonius Rufus belonged to. (Those two are long dead now, by the way.) What that means is that in addition to all the training a young prince receives – sitting with his father during court deliberations, following debates in the Senate, learning to speak, and learning to hunt – he is putting himself through a regimen of reading, spiritual reflection, and ascetic denial. For that reason he tends to avoid court dinners, unless Pius insists that he be present, and requests what he thinks of as poor people’s food to eat – bread and vegetables.”

What about the duck?

“He has a weakness for duck.”

The sun had just set, and a warm spring wind blew through the flower garden outside, which carried a whiff of fragrance up to our perch. The moon was bright in the east, but there were no stars yet.

Perfect Passive and Future Active Infinitives

“Before it gets too dark, let’s review the forms of the infinitive. There are five forms in regular use, and you have already learned three of these: the present active, amāre ‘to love’, the present passive, amārī, ‘to be loved’, and the perfect active, amāvisse ‘to have loved’. Now you’ll learn the other two forms: the perfect passive infinitive, amātum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse ‘to have been loved’ and the future active infinitive, amātūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse ‘to be about to love’.”

The Perfect Passive Infinitive

“The perfect passive infinitive is like the perfect passive tense: it consists of an accusative form of the perfect passive participle, plus esse. On its own, it means ‘to have been verbed’. For example, amātum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse ‘to have been loved’. You will also soon learn how to decide which one of those accusative endings you should use.”

The Future Active Infinitive

“The future active infinitive is similar to the perfect passive: it consists of an accusative form of the future active participle, plus esse. It is, however, translated actively: ‘to be about to verb’, ‘to be going to verb’. For example, amātūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse ‘to be about to love’.”

Review of Infinitive Forms

| Conj. | Pres. Act. | Pres. Pass. | Perf. Act. | Perf. Pass. | Fut. Act. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Verb (1st) | amāre | amārī | amāvisse | amātum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse | amātūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| E-Verb (2nd) | movēre | movērī | mōvisse | mōtum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse | mōtūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| I-Verb (3rd) | dīcere | dīcī | dīxisse | dictum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse | dictūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| Mixed I-Verb | capere | capī | cēpisse | captum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse | captūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| Long I-Verb (4th) | audīre | audīrī | audīvisse | audītum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse | audītūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| Irregular | ferre | ferrī | tulisse | lātum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse | lātūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| Irregular | īre | īrī | īvisse | itum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse | itūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| Irregular | esse | –––––– | fuisse | ––––––––––––––––– | futūrum (/ am / um / ōs / ās / a) esse |

| Irregular | velle | –––––– | voluisse | ––––––––––––––––– | –––––––––––––––––– |

Drill

“Provide the five infinitive forms of these verbs, and translate each form:”

| Latin Verb Principal Parts | Present Active Infinitive | Present Passive Infinitive | Perfect Active Infinitive | Perfect Passive Infinitive | Future Active Infinitive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pugnō, pugnāre, pugnāvī, pugnātus | |||||

| teneō, tenēre, tenuī, tentus | |||||

| legō, legere, lēgī, lēctus |

Indirect Statement

“Now you are ready for our main lesson today, which is on indirect statement. An indirect statement is any statement that is introduced by a verb of speaking, thinking, perceiving, or feeling. ‘He loves Rome’ is a direct statement. By contrast, ‘I know that he loves Rome’ contains an indirect statement: ‘I know’ is a verb of thinking, and it introduces the indirect statement ‘that he loves Rome’.”

Accusative and Infinitive in Indirect Statement

“In Latin, an indirect statement consists of two essential parts, an accusative form, and an infinitive. The infinitive is the verb of the indirect statement, and the accusative form is the subject of the indirect statement. Here is an example:”

| Sciō eum Rōmam amāre. | Latin |

| Sciō (verb of knowing; introduces indirect statement) eum (accusative pronoun, subject of indirect statement) Rōmam (accusative d. o.) amāre (pres. act. infinitive, verb of indirect statement). | Grammar Analysis |

| I know <that> he loves Rome. | English |

“Notice how we must provide the word ‘that’ when we translate the indirect statement into English.”

Translating an Accusative Subject in Indirect Statement

“In the example above, I translated the accusative pronoun eum as ‘he’. This is because indirect statements work differently in English than in Latin: in English, after the word ‘that’ you get a new subject and a conjugated verb. You must translate the accusative subject of a Latin indirect statement with the appropriate subject form in English:”

Translating an Accusative Pronoun in Indirect Statement: Examples

| Latin Pronoun (Sg.) | English Translation | Latin Pronoun (Pl.) | English Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| mē | I (not ‘me’) | nōs | we |

| tē | you | vōs | you all |

| eum | he (not ‘him’) | eōs | they (not ‘them’) |

| eam | she (not ‘her’) | eās | they (not ‘them’) |

| id | it | ea | they |

| sē | he, she, it | sē | they |

“The pronoun sē, as usual, refers to the subject of the sentence (the subject of the verb that introduces the indirect statement). The translation of sē depends on the gender and number of the subject.”

Translating Reflexive sē in Indirect Statement: Example

| Illa fēmina sē Rōmam amāre dīcit. | Latin |

| That woman says that she (= illa fēmina, the subject of dīcit) loves Rome. | English |

Translating an Infinitive in Indirect Statement

“In the example Sciō eum Rōmam amāre, ‘I know that he loves Rome’, the infinitive amāre is translated ‘loves’, as if it were present tense amat. In translation, we must take the Latin infinitive and conjugate the English verb to match the subject of the indirect statement. Consider these examples:”

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Videō eum bonum esse. | I see <that> he is good. |

| Videō hōs virōs bonōs esse. | I see <that> these men are good. |

“In the first example, esse is translated ‘is’, to match the ‘he’ (eum) subject of the indirect statement. In the second example, esse is translated ‘are’ to match the ‘these men’ (hōs virōs) subject of the indirect statement. Notice also how the predicate (bonum, bonōs) is accusative, in agreement with the accusative subject. This same kind of agreement is required with the accusative participle in the perfect passive and future active infinitives that you just learned:”

| Latin | Engliah |

|---|---|

| Putō eum Rōmam amātūrum esse. | I think <that> he is going to love Rome. |

| Putō hōs virōs Rōmam amātūrōs esse. | I think <that> these men are going to love Rome. |

“In the first example the participle in the future infinitive amātūrum esse agrees with the subject accusative eum; in the second example the participle in amātūrōs esse agrees with the subject accusative hōs virōs.”

Verb Tense in Indirect Statement

“The tense of the infinitive in indirect statement is relative to the tense of the main verb of the sentence. This means that a present infinitive occurs at the same time as the main verb; a perfect infinitive occurs before the main verb; a future infinitive occurs after the main verb. Consider these examples:”

| Latin | Engliah |

|---|---|

| Sciō eum Rōmam amāre. | I know <that> he loves Rome. |

| Videō eum Rōmam amāvisse. | I see <that> he loved Rome. |

| Putō eum Rōmam amātūrum esse. | I think <that> he is going to love Rome. |

Exercises 1-8

1. Puella sē Rōmae esse dīcit.

2. Iuvenis sē domī fuisse dīcit.

3. Sorōrēs sē ad urbem itūrās esse dīcunt.

4. Scīmus illum deum optimum atque maximum esse.

5. Videō vōs lūdere mālle, sed ego discere mālō.

6. Putāsne quemque hominem eadem timēre?

7. Sentītis hanc virginem longiōre vītā dignissimam esse.

8. Caedem Pompēiīs ortam esse audiō.

Translating an Infinitive in Indirect Statement, Continued

“When the verb of speaking, thinking, perceiving, or feeling that introduces an indirect statement is past tense (imperfect, perfect, or pluperfect), it affects the translation of the infinitive in the indirect statement. For example, a present infinitive is ‘present’ relative to the past tense main verb, meaning the action of the infinitive was happening at the same time as the action of speaking, thinking, perceiving, or feeling:”

Translating an Infinitive in Indirect Statement Introduced by a Past Tense Verb

| Main Verb Tense | Infinitive Verb Tense | Translation | Time "Action" or Relationship of Infinitive to Main verb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past | Present | ‘verbed’ (active); ‘was/were verbed’ (passive). | Simultaneous |

| Past | Perfect | ‘had verbed’ (act.); ‘had been verbed’ (pass.) | Prior |

| Past | Future | ‘would verb’. | Subsequent |

“Here are some examples to illustrate:”

| Latin | English |

|---|---|

| Vīdī eum Rōmam amāre. | I saw that he loved Rome. |

| Putāvī eum Rōmam amāvisse. | I thought that he had loved Rome. |

| Scīvī eum Rōmam amātūrum esse. | I knew that he would love Rome. |

Exercises 9-12

9. Iuvenis sē domī futūrum esse dīxit.

10. Sēnsī amīcum nostrum trīstissimum esse.

11. Scīvimus Caesarem hostēs vīcisse.

12. Mulierēs urbem suam captam esse ab Rōmānīs audīvērunt.

Ordinal Numbers

“One more thing. When we read this letter that Marcus wrote, you are going to see several ordinal numbers in it. Those are numbers that indicate the position of something in a list; in English, most of them end with ‘-th’. They are US-A-UM (first and second declension) adjectives in Latin. Starting with the number three, they resemble the cardinal numbers, but with altered stems:”

| Cardinal Numbers | English Meaning | Ordinal Numbers | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ūnus, a, um | one | prīmus, a, um | first |

| duo, duae, duo | two | secundus, a, um | second |

| trēs, tria | three | tertius, a, um | third |

| quattuor | four | quārtus, a, um | fourth |

| quīnque | five | quīntus, a, um | fifth |

| sex | six | sextus, a, um | sixth |

| septem | seven | septimus, a, um | seventh |

| octō | eight | octāvus, a, um | eighth |

| novem | nine | nōnus, a, um | ninth |

| decem | ten | decimus, a, um | tenth |

Vocabulary

A-Verb (First Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| dēsīderō, dēsīderāre, dēsīderāvī, dēsīderātus | to desire; miss |

Deponent A-Verb (First Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| moror, morārī, morātus sum | to delay; linger |

E-Verb (Second Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| studeō, studēre, studuī + dat. | to be eager; study. “The object of this verb will be in the dative case.” |

Impersonal E-Verb (Second Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| libet, libēre, libuit / libitum est + dat. + inf. | it is pleasing. “An infinitive states what it is pleasing to do; a dative the person to whom it is pleasing.” |

I-Verb (Third Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| fundō, fundere, fūdī, fūsus | to pour; pour forth |

Deponent I-Verb (Third Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| proficīscor, proficīscī, profectus sum | to set out |

Mixed I-Verb (Third Conjugation -iō)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| recipiō, recipere, recēpī, receptus | to take back; withdraw. “With a reflexive pronoun it means ‘to withdraw’: mīles sē recēpit ‘the solider withdrew (took himself back)’.” |

Exercises 13-15

13. Libet nōbīs prīmā lūce proficīscī.

14. Tūtī et integrī equitēs in silvās sē recēpērunt.

15. Nōnne pācī studētis? Parumne sanguinis fūsum est?

Vocabulary

First Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| hōra, hōrae | f. | hour; season |

Second Declension Nouns

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| cibus, cibī | m. | food |

| magister, magistrī | m. | teacher; master |

Third Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| ōrātiō, ōrātiōnis | f. | speech |

Adverbs

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| hodiē | today |

| ita | so; in this way |

| quantum | how much; as much as |

Conjunction

| Latin Conjunction | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| an | (whether) ... or; or? |

Exercises 16-21

16. Varium cibum dēsīderāmus, sed frūmentum sōlum domī habēmus.

17. Nōnne partem prīmam huius ōrātiōnis ā magistrō tuō didicistī? An eī nōn studuistī?

18. Rōmānī hodiē pudōrem rīdent et, ut Iuvenālis dīcit, paucī morantur eum fugientem ex urbe.

19. In the ninth hour the older sister of the teacher gave a fourth part of the food to her third son. “In Latin you say that a sibling is ‘greater’ or ‘lesser’ in age.”

20. In this way we set out, about to pour water, as much as is possible, onto the fire.

21. Because I miss Rome, it is pleasing to me to set out soon, and not to study those poems.

Marcus Aurelius and Fronto

“So,” Latinitas said, cracking the wax seal on the letter, “let’s see what young Marcus has to say. This letter is written to his mentor Fronto, Mārcus Cornēlius Frontō. At the moment, Fronto is the most respected living authority on Latin prose style; he has a small school of eager disciples, the Frontōniānī, who, like Marcus Aurelius, are absolutely devoted to him. He likes to hold up the old-fashioned Latin of Cato the Elder as a model for people to copy, and has his students read Cato’s speeches. Fronto was North African, like many Roman writers we will be meeting in the next few days; his hometown is the city of Cirta, west of Carthage. He has worked his way up through the imperial hierarchy, and this year he will be appointed consul.”

“Fronto is currently in Rome, and Marcus has been sending him daily updates from the villa.”

She shared the text of Marcus Aurelius’ letter to Fronto with me:

Marcus Aurelius’ Letter to Fronto

“Read the Latin aloud and, with a partner, attempt to work out the meaning for the sections that include vocabulary help below them. For the translated section, answer the questions below it:”

1) Havē mihi magister cārissime. Nōs valēmus. Ego hodiē ab hōrā nōnā noctis in secundam diēī, bene dispositō cibō, studīvī; ā secundā in tertiam soleātus libentissimē inambulāvī ante cubiculum meum. Deinde calceātus, sagulō sūmptō (nam ita adesse nōbīs indictum erat), abiī salūtātum dominum meum.

dispōnō, dispōnere, disposuī, dispositus to arrange; distribute at intervals (Marcus did not eat full meals)

studīvī (a colloquial form) = studuī

soleātus, a, um wearing sandals

libentissimē from libēns, libentis, present active participle (adjective) of libet

inambulō, inambulāre, inambulāvī to pace

cubiculum, cubiculī, n. bedroom

calceātus, a, um wearing shoes

sagulum, ī, n. purple general’s cloak

adsum, adesse, adfuī to be present

indīcō, indīcere, indīxī, indictus to proclaim; ordain

salūtātum ‘to greet’ (expressing purpose)

2) Ad vēnātiōnem profectī sumus, fortia facinora fēcimus, aprōs captōs esse fandō audīmus, nam videndī quidem nūlla facultās fuit. Clīvom tamen satis arduum successimus; inde post merīdiem domum recēpimus. Ego mē ad libellōs.

We set out for the hunt, we did brave deeds, we heard that boars had been captured from hearsay, for indeed there was no chance of seeing them. Nevertheless, we went up a sufficiently steep hill; then after noon we returned home. I (took) myself to my books.

Questions

profectī sumus Person, number, and tense?

facinora How translated? What is the usual meaning of this word?

aprōs captōs esse ... audīmus: audīmus = audīvīmus; What case is aprōs? What form is captōs esse?

recēpimus How translated?

3. Igitur calceīs dētractīs, vestīmentīs positīs in lectulō, ad duās hōrās commorātus sum. Lēgī Catōnis ōrātiōnem dē bonīs Pulchrae… “Iō”, inquis puerō tuō, “vāde quantum potes, dē Apollonis bibliothēcā hās mihi ōrātiōnēs adportā.” Frūstrā: Nam duo istī librī mē secūtī sunt….

calceus, -ī, m. shoe

dētrahō, dētrahere, dētraxī, dētractus to pull off

vestīmentum, vestīmentī, n. clothing

lectulus, lectulī, m. bed

commoror, commorārī, commorātus sum ~ moror, morārī, morātus sum

dē bonīs Pulchrae On the Goods/Property of Pulchra (a title)

iō hey!

vādō, vādere, vāsī to rush

Apollonis bibliothēcā the library of Apollo (built under Augustus)

adportō, adportāre, adportāvī adportātus to carry to

iste, ista, istud that; those (similar to ille, illa, illud)

4. Sed ego, ōrātiōnibus hīs perlēctīs, paululum miserē scrīpsī quod aut Lymphīs aut Volcānō dicārem…

perlego, perlegere, perlēgī, perlēctus the prefix per- adds ‘thoroughly’ to the verb’s meaning

paululus, -a, -um a very little (bit)

Lympha, -ae, f. water-goddess, referring to the waste-disposal in the drain

Volcānus, -ī, m. Vulcan, god associated with fire

dicārem ‘I would like to dedicate’, from dicō, dicāre, dicāvī, dicātus

5. Ego videor mihi perfrīxisse; quod māne soleātus ambulāvī, an quod male scrīpsī, nōn sciō. Certē homō aliōquī pītuītōsus, hodiē tamen multō mūcculentior mihi esse videor.

perfrīgēscō, perfrīgēscere, perfrīxī to catch a cold

māne in the (early) morning

certus, -a, -um certain

aliōquī otherwise; at other times

pītuītōsus, -a, -um runny-nosed; full of phlegm

mūcculentus, -a, -um full of mucus

6. Itaque oleum in caput īnfundam et incipiam dormīre, nam in lucernam hodiē nūllam stillam inicere cōgitō, ita mē equitātiō et sternūtātiō dēfetīgāvit. Valēbis mihi magister cārissime et dulcissime, quem ego, ausim dīcere, magis quam ipsam Rōmam dēsīderō.

oleum, oleī, n. oil

īnfundō, īnfundere, īnfūdī, īnfūsus the prefix in- adds ‘onto’ to the verb’s meaning

lucerna, lucernae, f. lamp

stilla, stillae, f. drop

iniciō, inicere, iniēcī, iniectus to throw into; put into

equitātiō, equitātiōnis, f. (act of) riding

sternūtātiō, sternūtātiōnis, f. (act of) sneezing

dēfetīgō, dēfetīgāre, dēfetīgāvī, dēfetīgātus to fatigue; wear out

ausim ‘I would dare’, from audeō, audēre, ausus sum

When I finished studying it, she closed it up again. She said she would deliver it to Fronto later, and stuff it under his pillow.

By now it was quite dark, and stars had joined the moon in the sky. Latinitas then did something that took my breath away. She put a bit of cloud beneath our feet, then raised her right hand. At once the cloud carried us upward through the air, very fast. It was like being in an airplane after it has taken off: we saw Rome below us, faintly lit by nighttime fires, then Ostia and the cities of Latium and Tuscany, very dim but unmistakable. Soon after that we could see the Mediterranean shimmering in the sun, which appeared to slowly climb in the west as we got higher and higher. A few minutes later we could look down and see the whole world. I guess this view of earth hasn’t changed that much since antiquity, except that there are many more lights on the night side now, and the polar cap is smaller than it was then.

Before Latinitas sent me back to my apartment, she let me have a look at the moon and the sun and the planets and stars all around us, and one last glance at the earth, which was shrinking in the distance to a pale blue dot.

“Remember this view. Philosophers like Marcus Aurelius used to spend their whole lives trying to get this kind of perspective on the world using nothing but their imagination. You can see it with your own eyes.”

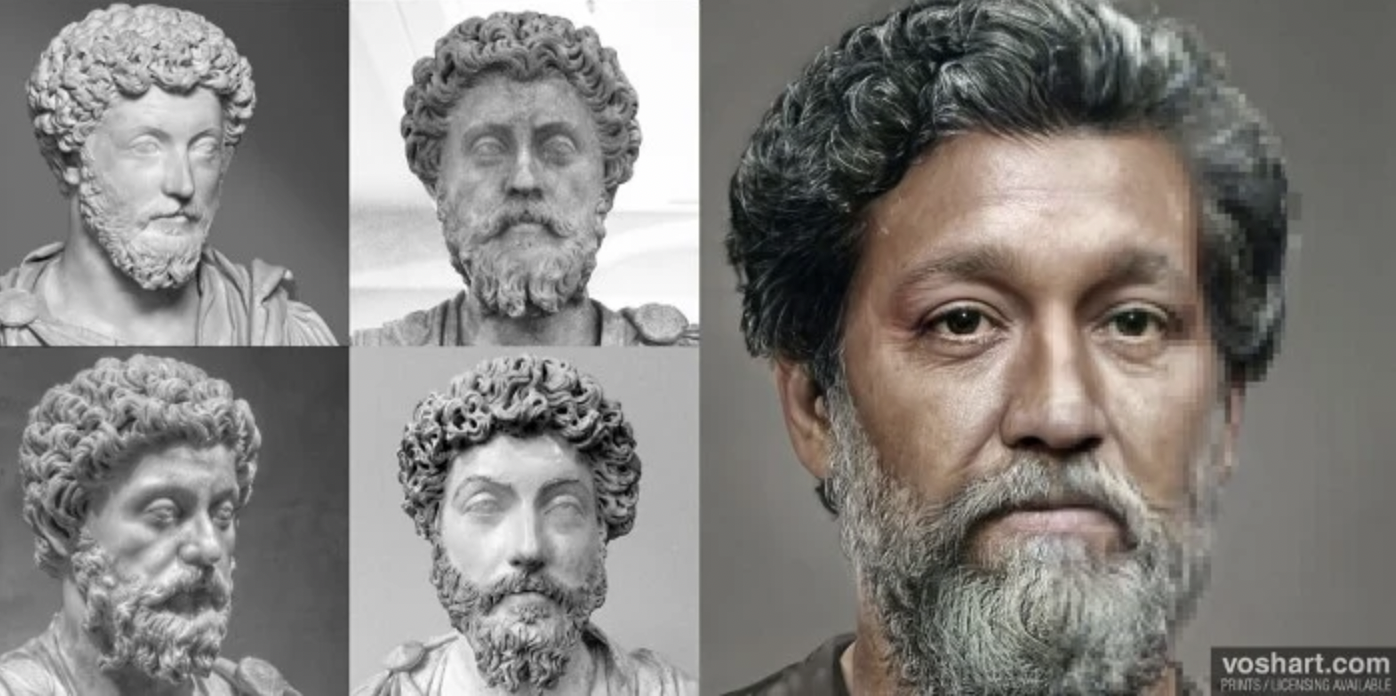

62. A recent reconstruction of how Marcus Aurelius may have looked when he was emperor, based on ancient portrait busts. The particular details of his hair, skin, and eye coloring are largely conjectural; notice also how his curls, especially in his beard, have been downplayed. Omnēs refectūs novī magnō cum grānō salis accipiendī sunt; all modern reconstructions should be taken with a large grain of salt.