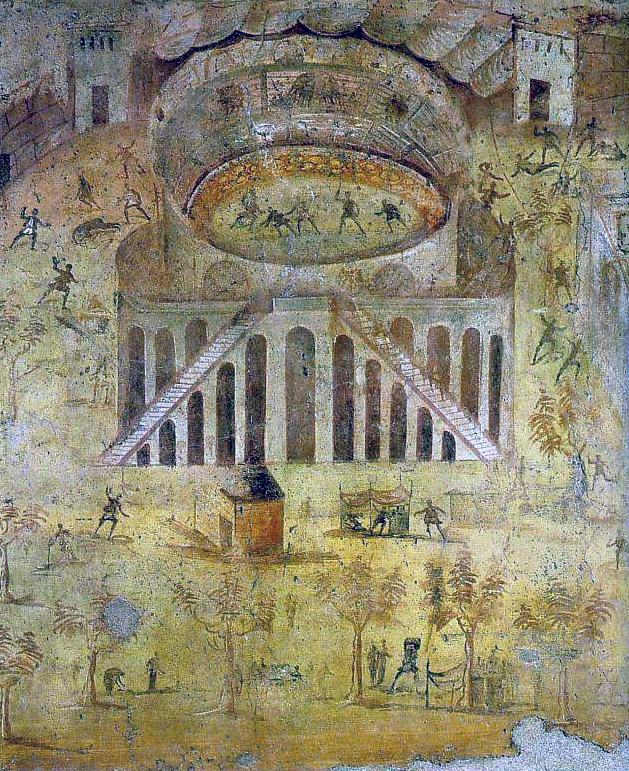

52. A fresco painting from Pompeii showing the amphitheater where gladiatorial combats were held, as well as the riot that took place there in 59 CE. Notā bene vēla, quae umbram spectātōribus offerrent. Note the awnings, which were designed to provide shade for the spectators.

Explōrātiō Vīcēnsima Quarta (XXIV) Adventure Twenty-Four

Local History: A Riot in Pompeii

Tacitus’ Annālēs: An Account of the Riot

Formation of the Comparative Adjective

Declension of the Comparative Adjective

Omitted sum in the Perfect Passive

Senceca the Younger’s Epistulae Mōrālēs ad Lūcīlium

Seneca the Younger’s Letter to Lucilius: Excerpt

Seneca the Younger’s Letter to Lucilius: Excerpt with Translation

Where and When Are We Today?

Pompēiī, Ītalia

Mēnsis September

C. Vipstānō Aprōniānō C. Fontēiō Capitōne cōnsulibus

Pompeii, Italy

September, 59 C.E.

A flock of black birds spiraled down from the blue sky and vanished into the branches of an umbrella pine just overhead. We were standing on a stone-paved road just outside the walls of a city, facing the exterior of what looked like a low football stadium made of stone. The city was Pompeii, and the stadium its amphitheater, the venue where gladiatorial shows were put on.

At the point where two stairways leading up the side of the amphitheater converged, we could see a Roman dignitary gesticulating his way through a conversation with several companions. Our view of them was obstructed momentarily by several donkey carts that were carrying loads of freshly picked grapes for a nearby winery. When we stepped out of the road to let them pass, a beggar with an ugly cut on his arm approached us with outstretched hands. Latinitas gave him what looked like a small gold coin from her purse; he kissed her hand and shouted loudly as he limped away to an encampment in the woods nearby. We crossed the road and made for the bottom of one of the stairs, where, Latinitas said, we would soon meet the dignitary; she called him the prōpraetor Lūcīlius.

Local History: A Riot in Pompeii

There was a backstory to our visit which Latinitas had filled in before we left the apartment. A few months earlier a local Pompeian magistrate named Regulus had put on a gladiatorial show in this amphitheater. This turned into a riot when fans of the local Pompeian fighters clashed with supporters of the gladiators from the nearby town of Nuceria. A picture of the riots survives on a Pompeian wall painting, illustrated above.

Before telling me the story, Latinitas first taught me a few new words:

Vocabulary

Deponent Long I-Verb (Fourth Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| orior, orīrī, ortus sum | to rise; arise |

Second Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| saxum, saxī | n. | rock |

Third Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| caedēs, caedis | f. | slaughter; killing |

Third Declension Adjective

| Latin Adjective | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| levis, leve | light; trivial |

Conjunction

| Latin Conjunction | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| ergō | so; therefore |

Adverb

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| numquam | never |

Preposition

| Latin Preposition + Case | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| contrā + acc. | against; to the contrary |

Tacitus’ Annālēs: An Account of the Riot

The Roman historian Tacitus recorded the story in the fourteenth book of his Annālēs. Working with a partner or two, read each selection and try to answer the questions below it.

1) Sub idem tempus levī initiō atrōx caedēs orta inter colōnōs Nucerīnōs Pompēiānōsque gladiātōriō spectāculō, quod Livinēius Rēgulus ēdēbat. Quippe oppidānā lascīviā in vicem incessentēs probra, dein saxa, postrēmō ferrum sūmpsēre, validiōre Pompēiānōrum plēbe, apud quōs spectāculum ēdēbātur.

In the same time period a deadly slaughter arose from a trivial beginning among the townspeople of Nuceria and Pompeii at a gladiatorial show which Livineius Regulus produced. For while they were taunting each other with small-town sassiness, they took up insults, then rocks, and finally swords, with the common people of Pompeii, on whose turf the show was produced, proving stronger.

Questions

idem tempus: Case and number?

levī: Dative or ablative?

caedēs: How translated?

inter: What word(s) does this preposition govern?

saxa: Nominative or accusative?

ferrum: How translated?

sūmpsēre: What form is this?

What is the Latin for ‘show’?

2) Ergō dēportātī sunt in urbem multī ē Nucerīnīs truncō per vulnera corpore, ac plērīque līberōrum aut parentum mortēs dēflēbant. Cuius reī iūdicium princeps senātuī, senātus cōnsulibus permīsit. Et rūrsus rē ad patrēs relātā, prohibitī pūblicē in decem annōs eius modī coetū Pompēiānī collēgiaque, quae contrā lēgēs īnstituerant, dissolūta; Livinēius et quī aliī sēditiōnem concīverant exiliō multātī sunt.

Therefore, many of the Nucerians were carried to the city, their bodies mutilated by wounds, and many of them were mourning the deaths of their children or parents. The Senate leader referred the judgment of this affair to the Senate, and the Senate referred it to the consuls. And when the affair was again referred back to the Senate, the Pompeians were prohibited from [holding] gatherings of this sort in public for ten years, and the clubs, which they had established illegally, were dissolved; Livineius and the others who had stirred up the unrest were punished with exile.

Questions

vulnera: Case and number?

līberōrum aut parentum: Case and number of each noun?

mortēs: Nominative or accusative?

dēflēbant: How translated?

princeps senātuī, senātus cōnsulibus: Case and number of each noun?

rūrsus: How translated?

contrā lēgēs: How translated?

concīverant: Tense and voice?

That was the back story to our visit to Pompeii today. Lucilius – a native of the city who had just finished a term as the governor of Sicily – had been discussing the results of the expulsion with some local Pompeian officials. They were trying to figure out what to do with the amphitheater, now that the gladiātōria spectācula were suspended.

While we waited for Lucilius to come down, we parked ourselves in an empty wooden structure which served as a concession stand on game days. There Latinitas explained to me how comparative adjectives work in Latin.

Comparative Adjectives

“A comparative adjective,” she started, “compares one thing to another, like ‘older’ in ‘I am older than you’. If, however, you just want to say that I am ‘old’, without any comparison, you are using what we call a positive adjective. Most all of the Latin adjectives you have learned so far have been positive adjectives, such as cārus, cāra, cārum, ‘dear’, or difficilis, difficile, ‘difficult’. Today you will learn about comparatives, so you will be able to say ‘dearer’ and ‘more difficult’ in Latin.

In English, comparative adjectives are formed either with the ending ‘-er’ or the word ‘more’ in front of the positive adjective:”

English Comparative Adjectives, Illustrated

| Formed with ‘more’ | Formed with ‘-er’ |

|---|---|

| more gorgeous | bigger |

| more exciting | denser |

| more valuable | happier |

| more catastrophic | redder |

Formation of the Comparative Adjective

“Most Latin adjectives make their comparative form by adding to the adjective stem the nominative singular ending -ior for the masculine and feminine, and the nominative singular ending -ius for the neuter. The genitive singular ending for all genders is -iōris. The comparative adjective then declines like a third declension adjective (like omnis, omne).

This rule applies regardless of the positive form of the adjective–whether it is US-A-UM (first and second declension) or third declension type–it doesn’t matter, the comparatives all end -ior, -iōris (m., f.), -ius, -iōris (n.).”

Formation of the Comparative Adjective: Examples

| Dictionary Entry (Positive Adjective) | Stem | Stem + Comparative Ending | Translation of Comparative |

|---|---|---|---|

| dūrus, dūr-a, dūrum ‘hard’ | dūr- | dūr-ior, dūr-iōris (m., f.), dūr-ius, dūr-iōris (n.) | harder |

| fort-is, forte ‘brave’ | fort- | fort-ior, fort-iōris (m., f.), fort-ius, fort-iōris (n.) | braver |

“And here is each of these examples declined in full; notice the third declension endings after the element -iōr-:”

Declension of the Comparative Adjective

| “harder” (from dūrus, dūr-a, dūrum ‘hard’) | “braver” (from fort-is, forte ‘brave’) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sg. | Masc., Fem. | Ntr. | Masc., Fem. | Ntr. |

| Nom. | dūr-ior | dūr-ius | fort-ior | fort-ius |

| Gen. | dūr-iōris | dūr-iōris | fort-iōris | fort-iōris |

| Dat. | dūr-iōrī | dūr-iōrī | fort-iōrī | fort-iōrī |

| Acc. | dūr-iōrem | dūr-ius | fort-iōrem | fort-ius |

| Abl. | dūr-iōre/ī | dūr-iōre/ī | fort-iōre/ī | fort-iōre/ī |

| Pl. | ||||

| Nom. | dūr-iōrēs | dūr-iōra | fort-iōrēs | fort-iōra |

| Gen. | dūr-iōrum | dūr-iōrum | fort-iōrum | fort-iōrum |

| Dat. | dūr-iōribus | dūr-iōribus | fort-iōribus | fort-iōribus |

| Acc. | dūr-iōrēs/īs | dūr-iōra | fort-iōrēs/īs | fort-iōra |

| Abl. | dūr-iōribus | dūr-iōribus | fort-iōribus | fort-iōribus |

Drill

“Translate first the Latin noun and comparative adjective pairs, and identify their case and number (more than one identification may be possible). Then translate the English phrases into the specified case and number:”

| potestās saevior; faciliōrem labōrem; trīstiōribus fēminīs; bellum dūrius |

| more convenient plans (nom. pl.); the safer road (abl. sg.); for the braver soldiers (dat. pl.); more famous kings (acc. pl.) |

Exercises 1-7

1. Molliōrēs sunt amōris dulciōris vōcēs.

2. Tardiōra fāta tē manent ob hoc facinus: vītam miseriōrem agēs.

3. Numquam exemplum dulcius, numquam commodius vīdī.

4. Omnis nōmina nōbiliōra, ōra pulchriōra, etiam vōcēs nōtiōrēs laudat.

5. In rē nostrā testēs clāriōrēs nōs iuvābunt cum ante rēgem stābimus.

6. With fortune (having been) changed, I lost my more beautiful (things).

7. Because of a trivial error, I will lead a sadder life.

Synopsis of Verb Forms

“Now we will practice a useful tool for reviewing the forms of a verb in terms of tense and voice. It is called a synopsis (compare Explōrātiō 22: Synopsis of Verb Forms). I will give you a verb, and specify a person, number, and gender, and you write all the active and passive forms in Latin, plus the imperatives, infinitives, and present active and perfect passive participles, along with their English translations. As an example, let’s try a synopsis of amō, amāre, amāvī, amātus ‘to love’, in the third-person singular, masculine:”

Synopsis of amō, amāre, amāvī, amātus ‘to love’ Third-Person Singular, Masculine

| Latin Form | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Passive | Active | Passive | |

| Present | amat | amātur | he loves | he is loved |

| Imperfect | amābat | amābātur | he was loving | he was being loved |

| Future | amābit | amābitur | he will love | he will be loved |

| Perfect | amāvit | amātus sum | he loved/has loved | he was loved/have been loved |

| Pluperfect | amāverat | amātus eram | he had loved | he had been loved |

| Pres. Inf. | amāre | amārī | to love | to be loved |

| Perf. Inf. | amāvisse | [not yet learned] | to have loved | [not yet learned] |

| Impv. Sg. | amā | amāre | love! (sg.) | be loved! (sg.) |

| Impv. Pl. | amāte | amāminī | love! (pl.) | be loved! (pl.) |

| Pres. Act. Participle | amāns, amantis | ____________ | loving | ____________ |

| Pf. Pass. Participle | ____________ | amātus, amātī | ____________ | (having been) loved |

“Now let’s do a synopsis of a deponent verb. This has half as many forms, because there are only passive forms, except for the present participle. This time we will use precor, precārī, precātus sum ‘to pray’, in the second-person singular, feminine:”

Synopsis of precor, precārī, precātus sum ‘to pray’ Second-Person Singular, Feminine

| Latin Form | English Meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | precāris/re | you pray |

| Imperfect | precābāris/re | you were praying |

| Future | precāberis/re | you will pray |

| Perfect | precāta es | you prayed/have prayed |

| Pluperfect | precāta erās | you had prayed |

| Pres. Inf. | precārī | to pray |

| Perf. Inf. | [not yet learned] | [not yet learned] |

| Impv. Sg. | precāre | pray! (sg.) |

| Impv. Pl. | precāminī | pray! (pl.) |

| Pres. Act. Participle | precāns, precantis | praying |

| Pf. Pass. Participle | precāta, precātae | having prayed |

Drill

“Now try these two synopses, using the examples above as a guide:”

Synopsis of dīcō, dīcere, dīxī, dictus ‘to say’ Third-Person Plural, Feminine

| Latin Form | English Translation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Passive | Active | Passive | |

| Present | ||||

| Imperfect | ||||

| Future | ||||

| Perfect | ||||

| Pluperfect | ||||

| Pres. Inf. | ||||

| Perf. Inf. | [not yet learned] | [not yet learned] | ||

| Impv. Sg. | ||||

| Impv. Pl. | ||||

| Pres. Act. Participle | ____________ | ____________ | ||

| Pf. Pass. Participle | ____________ | ____________ | ||

Synopsis of mīror, mīrārī, mīrātus sum ‘to admire’ First-Person Plural, Masculine

| Latin Form | English Meaning | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | ||

| Imperfect | ||

| Future | ||

| Perfect | ||

| Pluperfect | ||

| Pres. Inf. | ||

| Perf. Inf. | [not yet learned] | [not yet learned] |

| Impv. Sg. | ||

| Impv. Pl. | ||

| Pres. Act. Participle | ||

| Pf. Pass. Participle |

Somewhat grudgingly I obeyed, and I have to admit it was clarifying. I was waiting for Lucilius to come down and rescue me from all this grammar, but his friends kept holding him back, which gave Latinitas time to add one more thing.

Omitted sum in the Perfect Passive

“One more thing. When Roman speakers and authors use the perfect passive, they sometimes just give the perfect passive participle, and leave out the form of the verb sum, particulary when the verb is third-person singular or plural. As a result, you might see a sentence like this:”

Vīsī hostēs ante moenia; mox vocātus noster dux.

“In this situation, this is what you should do: IF a sentence has a nominative perfect passive pariticple but no form sum, AND there is no other main verb with personal endings, THEN supply est if the participle is singular, or supply sunt if the participle is plural.”

Translating a Sentence with a Perfect Passive Verb Lacking a Form of sum: Example

| Vīsī hostēs magnō in aequore; mox vocātus noster dux. |

| There are two nominative participles, vīsī, vocātus, but no form of sum and no other main verb. |

| So, supply sunt with vīsī (nom. masc. pl.), and est with vocātus (nom. masc. sg.). |

| Vīsī <sunt> hostēs ante moenia; mox vocātus <est> noster dux. |

| The enemies were seen before the walls; soon our leader was called. |

“Here is another example, from the Tacitus passage that you read earlier:”

Translating a Sentence with a Perfect Passive Verb Lacking a Form of sum: Example

| Atrōx caedēs orta inter colōnōs Nucerīnōs Pompēiānōsque. |

| There is one nominative participle, orta, but no form of sum and no other main verb. |

| So, supply est with orta (nom. fem. sg.). |

| Atrōx caedēs orta <est> inter colōnōs Nucerīnōs Pompēiānōsque |

| A deadly slaughter arose between the inhabitants of Nuceria and Pompeii. |

Exercises 8-10

8. Līberātī ā principe paene centum servī.

9. Aurea et argentea ab hostibus rapta.

10. Frāctus et victus noster exercitus.

“Now add these words to your book; you are going to encounter them in a minute.”

Vocabulary

I-Verbs (Third Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| discō, discere, didicī | to learn |

| intellegō, intellegere, intellēxī, intellēctus | to understand |

| occīdō, occīdere, occīdī, occīsus | to strike dead; kill |

Deponent I-Verb (Third Conjugation)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| nāscor, nāscī, nātussum | to be born; grow |

Deponent Mixed I-Verb (Third Conjugation -iō)

| Latin Verb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| patior, patī, passus sum | to suffer; allow |

First Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| mora, morae | f. | delay |

Second Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| vitium, vitiī | n. | vice; flaw |

Third Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| voluptās, voluptātis | f. | pleasure |

Fourth Declension Noun

| Latin Noun | Noun Gender | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| cāsus, cāsūs | m. | chance event; accident; misfortune “The ablative cāsū means ‘by chance’.” |

Adjective / Pronoun

| Latin Adjective / Pronoun | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| aliquis, aliquid | some; any (used as an adjective) someone; anyone; something; anything (used as a pronoun) “This word declines like quis (m., f.), quid (n.), with ali- attached.” |

Adverbs

| Latin Adverb | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| frūstrā | in vain |

| immō or immōvērō | actually “Introduces a qualification or contradiction.” |

| tam | so |

| tam… quam | so… as… |

| tunc | then |

Conjunction

| Latin Conjunction | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| quia | because |

Interrogative

| Latin Interrogative | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| quārē | how?; why? |

Preposition

| Latin Preposition + Case | English Meaning |

|---|---|

| inter + acc. | among |

Exercises 11-17

11. Vitium huius principis ā cupīdine nātum.

12. Tunc aliquis vulnera passus, aliquis occīsus, aliquis mortuus, quia populus eōs servāre nōn poterat.

13. Nōn cāsū advēnēre; immō vērō omnēs fāta deōrum secūtī.

14. Frūstrā sapiēns docuit, nam mentēs audientium nōn intellēxērunt.

15. Voluptās nōn tam commoda hominibus quam dulcis est.

16. Tunc dux sine morā arma sūmpsit et inter mīlitēs stetit.

17. Quārē haec mulier tam multa scrīpsit manū suā atque trādidit? Quia litterās ā mātre didicerat.

We paused for a minute to look around. There was a tall mountain looming off in the distance.

“That’s Vesuvius,” Latinitas said, “the volcano. The one that will erupt in twenty years.”

Oh my god, I said out loud. We are visiting that Pompeii, the lost city. It hasn’t been destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius yet!

Shouldn’t we tell the people who live here? I asked her. Shouldn’t we tell everyone? Twenty years is a long time. They could move somewhere safe.

“We should, but… do you know the story of Cassandra? The Trojan prophetess who was cursed never to be believed?”

Yeah.

“The same thing would happen. We could tell them the truth, but why should anyone believe you or me? You don’t even speak Latin.”

That stung. I was sure I could string together something. I looked her in the eye and said, slowly, Vīgintī annīs, ille mōns explōdet, occīdēns vōs omnēs. Cavēte!

She turned her head slightly to the right, and looked at me without blinking. In my gut I knew she was right. Once again I had to swallow the awful truth: there was nothing I could do to change the past; the tragedy was already baked in.

Senceca the Younger’s Epistulae Mōrālēs ad Lūcīlium

Lucilius was coming down the stairs, right towards us. I felt bad for him and his beloved city, enough that I lost the terror that usually rose in me whenever I thought an ancient Roman might speak to me. Latinitas greeted him. To explain her presence, she made up a story; she said she was a student of the philosopher Musonius Rufus, and a friend of the philosopher Seneca, and that I in turn was her student. We were on our way south from Rome and she was bearing a letter from Seneca to Lucilius. As Latinitas later confided to me, this letter for Lucilius was one of Seneca the Younger’s Epistulae Mōrālēs ad Lūcīlium, or Moral Letters to Lucilus.

She handed Lucilius the letter, and then introduced me; she said she was teaching me, a ‘barbarian’, how to speak Latin. Lucilius was a thin-framed man with a kind look on his face and very disorganized hair. He opened the letter and handed it to me, saying: Hoc mī lege, Read this to me.

I took Seneca’s letter from Lucilius’ hands and read it out loud. My voice was shaky at first, but by paying attention to each word, I was able to forget my anxieties:

Seneca the Younger’s Letter to Lucilius: Excerpt

Practice reading the Latin aloud. If you want to, use the audio recorder to record the Latin test and listen to yourself reading.

Nihil vērō tam damnōsum bonīs mōribus quam in aliquō spectāculō dēsidēre; tunc enim per voluptātem facilius vitia subrēpunt. Quid mē exīstimās dīcere? Avārior redeō, ambitiōsior, luxuriōsior? Immō vērō crūdēlior et inhūmānior, quia inter hominēs fuī.

Cāsū in merīdiānum spectāculum incīdī, lūsūs exspectāns et salēs et aliquid laxāmentī quō hominum oculī ab hūmānō cruōre acquiēscant. Contrā est: quidquid ante pugnātum est misericordia fuit; nunc omissīs nūgīs mera homicīdia sunt. Nihil habent quō tegantur; ad ictum tōtīs corporibus expositī numquam frūstrā manum mittunt.

Hoc plērīque ōrdināriīs paribus et postulātīciīs praeferunt. Quidnī praeferant? Nōn galeā, nōn scūtō repellitur ferrum. Quō mūnīmenta? Quō artēs? Omnia ista mortis morae sunt. Māne leōnibus et ursīs hominēs, merīdiē spectātōribus suīs obiciuntur.

Interfectōrēs interfectūrīs iubent obicī et victōrem in aliam dētinent caedem; exitus pūgnantium mors est. Ferrō et igne rēs geritur. Haec fīunt dum vacat harēna. ‘Sed latrōcinium fēcit aliquis, occīdit hominem’.

Quid ergō? Quia occīdit, ille meruit ut hoc paterētur: tū quid meruistī miser ut hoc spectēs? ‘Occīde, verberā, ūre! Quārē tam timidē incurrit in ferrum? Quārē parum audācter occīdit? Quārē parum libenter moritur? Plāgīs agātur in vulnera, mūtuōs ictūs nūdīs et obviīs pectoribus excipiant.’ Intermissum est spectāculum: ‘interim iugulentur hominēs, nē nihil agātur’.

Age, nē hoc quidem intellegitis, mala exempla in eōs redundāre quī faciunt? Agite dīs immortālibus grātiās quod eum docētis esse crūdēlem quī nōn potest discere.

When I was done, I handed it back to him. He smiled. Bene lēctum; sed prōnuntiā m leviter, nōn mm, graviter. ‘Well read; but pronounce ‘m’ lightly, not ‘mm’, strongly’.

As Lucilius walked away and left us on our own, I could feel the sweat trickling down my armpits.

When I got home to my apartment I looked up Seneca’s letter to Lucilius online, and worked on a translation of it, to see what I had read.

Seneca the Younger’s Letter to Lucilius: Excerpt with Translation

Work with a partner to complete the identifications and grammar questions below each translated selection:

1) Nihil vērō tam damnōsum bonīs mōribus quam in aliquō spectāculō dēsidēre; tunc enim per voluptātem facilius vitia subrēpunt. Quid mē exīstimās dīcere? Avārior redeō, ambitiōsior, luxuriōsior? Immō vērō crūdēlior et inhūmānior, quia inter hominēs fuī.

Nothing in fact is so damaging to good behavior as to sit down at some show; for then because of the pleasure, vices creep in more easy. What do you think I’m saying? I return more greedy, more power-hungry, more prone to luxury? No, actually, more cruel and inhuman, because I was among people.

Questions

Identify the comparative adjectives.

bonīs mōribus: Case and number?

per voluptātem: How translated?

vitia: Case and number?

fuī: What form is this?

2) Cāsū in merīdiānum spectāculum incidī, lūsūs exspectāns et salēs et aliquid laxāmentī quō hominum oculī ab hūmānō cruōre acquiēscant. Contrā est: quidquid ante pugnātum est misericordia fuit; nunc omissīs nūgīs mera homicīdia sunt. Nihil habent quō tegantur; ad ictum tōtīs corporibus expositī numquam frūstrā manum mittunt.

By chance I happened upon a midday show, expecting games and wit and some kind of relaxation by which human eyes might rest from human gore. It’s the reverse: whatever was fought previously was mercy; now, with small things left out, the murder is pure. They have nothing with which to cover themselves; exposed to blows with their entire bodies, they never launch a hand in vain.

Questions

Identify the present active participle.

hominum oculī: Case and number of each noun?

ante: How translated?

tōtīs corporibus: How translated?

manum: Case and number?

3) Hoc plērīque ōrdināriīs paribus et postulātīciīs praeferunt. Quidnī praeferant? Nōn galeā, nōn scūtō repellitur ferrum. Quō mūnīmenta? Quō artēs? Omnia ista mortis morae sunt. Māne leōnibus et ursīs hominēs, merīdiē spectātōribus suīs obiciuntur.

Most people prefer this to the ordinary pairs and duels. Why should they not prefer it? The sword is not repelled by helmet or shield. Why have protection? Why skill? All those things are delays for death. In the morning people are thrown to the lions and bears; at midday they are thrown to their own audience.

Questions

praeferunt: Active or passive voice?

ferrum: How translated?

mortis morae: Case and number of each noun?

spectātōribus suīs: Case and number?

obiciuntur: What tense, voice, person, and number?

4) Interfectōrēs interfectūrīs iubent obicī et victōrem in aliam dētinent caedem; exitus pūgnantium mors est. Ferrō et igne rēs geritur. Haec fīunt dum vacat harēna. ‘Sed latrōcinium fēcit aliquis, occīdit hominem’.

They order the killers to be thrown to those about to kill them, and detain the victor for another slaughter; death is the fighters’ exit. The business is conducted with sword and fire. These things happen while the sand/arena is empty. ‘But someone did a robbery, he struck dead a man.’

Questions

Identify the present active participle.

victōrem: Case and number?

in aliam ... caedem: How translated?

Ferrō et igne: Case and number of each noun?

fēcit ... occīdit: What tense, voice, person, and number?

5) Quid ergō? Quia occīdit, ille meruit ut hoc paterētur: tū quid meruistī miser ut hoc spectēs? ‘Occīde, verberā, ūre! Quārē tam timidē incurrit in ferrum? Quārē parum audācter occīdit? Quārē parum libenter moritur? Plāgīs agātur in vulnera, mūtuōs ictūs nūdīs et obviīs pectoribus excipiant.’ Intermissum est spectāculum: ‘interim iugulentur hominēs, nē nihil agātur’.

So what? Because he killed, he deserved that he should suffer this; what did you deserve, poor man, to watch this? ‘Kill, whip, burn! Why does he run towards the sword so timidly? Why does he kill with not enough boldness? Why does he die so unwillingly? Have him be driven to wounds with a beating, let them receive mutual blows with bare, facing chests!’ The show is at intermission; ‘in the meantime let’s have some men strangled, so that nothing won’t be happening’.

Questions

Identify the two interrogative adverbs (question words).

miser: How translated?

Occīde: What form is this?

in ferrum: How translated?

in vulnera: How translated?

6) Age, nē hoc quidem intellegitis, mala exempla in eōs redundāre quī faciunt? Agite dīs immortālibus grātiās quod eum docētis esse crūdēlem quī nōn potest discere.

C’mon, do you all not even understand this, that bad examples bounce back onto those who make them? Give thanks to the immortal gods because you all are teaching a man to be cruel who is unable to learn.

Questions

Identify the imperatives.

intellegitis: What is the person, number, tense, and voice?

quī: What is the antecedent?

discere: What form is this?

53. A mosaic depicting gladiators found in Spain, from the third century CE. In the upper register you can make out the words haec vidēmus, ‘we see these things’, Symmachī homō fēlīx, ‘Symmachius (you) lucky guy’, and the names Habilis and Māternus, the latter followed by the Greek letter theta, which stands for the Greek word θάνατος (thanatos), ‘death’. The lower register has the words quibus pugnantibus Symmachius ferrum mīsit, ‘at whom fighting Symmachius let loose his sword’, followed by Maternus with the death abbreviation and Habilis again. The unlabeled men represent gladiator trainers, lanistae. What do you think happened here?