33 Introduction to Interrogative Pronouns

“The pronoun quid, if you remember, means ‘what’. It has a partner, quis, which introduces a question and means ‘who’. It is an Interrogative Pronoun. It is called that because it introduces an interrogātiō, or a question. We will see these Interrogatives in Catullus’ poem:”

Interrogative Pronouns

quiswho?Nominative

cuiuswhose?Genitive

cuito/for whom?Dative

quemwhom?Accusative

quōprep. + whom?Ablative

Cuius vōx nōs ab lūce in noctem vocābat? (11)

To whom does the light of life not give pain, then anger? (12)

Who was having care of the girl? (13)

“That is how Latin says ‘care for’ – it uses the genitive, ‘care of’.”

“Now let’s go through the other poem we heard. First we will read the Latin, then take it section by section. I’ll let you adjust the English yourself, with some help.”

Miser Catūlle, dēsinās ineptīre,

et quod vidēs perisse perditum dūcās. Fulsēre quondam candidī tibi solēs, cum ventitābās quō puella dūcēbat amāta nōbīs quantum amābitur nūlla. Ibi illa multa cum iocōsa fīēbant, quae tū volēbās nec puella nōlēbat, fulsēre vērē candidī tibi sōlēs.

Nunc iam illa nōn vult: tū quoque impotēns nōlī, nec quae fugit sectāre, nec miser vīve,

sed obstinātā mente perfer, obdūrā. Valē puella, iam Catullus obdūrat, nec tē requīret nec rogābit invītam. At tū dolēbis, cum rogāberis nūlla. Scelesta, vae tē, quae tibi manet vīta?

Quis nunc tē adībit? Cui vidēberis bella? Quem nunc amābis? Cuius esse dīcēris? Quem bāsiābis? Cui labella mordēbis?

At tū, Catulle, dēstinātus obdūrā.

Miser Catūlle, dēsinās ineptīre,

et quod vidēs perisse perditum dūcās.

MiserableCatullus,you should ceaseto be naïve,

what has gone, gone (obj.) you should consider.

I stopped her: Why is he called Catulle here?

“When you call someone by name in Latin, you use what looks like the nominative form of their name: ō Catilīna, ō Clōdia. But when you call out a man whose name or title ends in –us, you replace the nominative –us ending with an –e:”

Ō Menaechme! Catulle!“Oh Menaechmus! Catullus!”

“And when you call a man whose name or title ends in –ius, you replace the –ius with –ī:”

Ō Terentī! Iulī! Avē, Gaī!“Oh Terentius! Julius! Hail, Gaius!”

“These forms are called the Vocative Case. But Latin proper names are always translated into their nominative form in English, so translate Catulle as ‘Catullus’.”

Fulsēre quondam candidī tibi solēs, cum ventitābās quō puella dūcēbat amāta nōbīs quantum amābitur nūlla.

They shoneoncewhite you were going where

the suns, was leading,

belovedby usas much aswill be lovedno woman (subj.).

“The word order of the first of these sentences is: verb, ‘they shone’; then ‘once’; then the predicate, ‘white’; then the dative pronoun; and finally the subject. So it should be reordered as, ‘Once the suns shone white for you.’”

Ibi illa multa cum iocōsa fīēbant, quae tū volēbās nec puella nōlēbat, fulsēre vērē candidī tibi sōlēs.

Therethosemany gameswere taking place,

which were wanting was not wanting,

they shonetrulywhite the suns.

“In the first line, cum comes late, but in English it needs to be translated near the start: ‘There, when those many games were taking place.’ (You saw this happen in our sentence from Cato: cum was the second word in the clause, praedium cum parāre cōgitābis.) The verbs that follow, volō and nōlō, mean ‘to want’ and ‘to not want’; they have a 3rd singular form, vult, and imperative, nōlī, which both come up in the next sentence.”

Nunc iam illa nōn vult: tū quoque impotēns nōlī, nec quae fugit sectāre, nec miser vīve,

sed obstinātā mente perfer, obdūrā.

that (woman) not wants; powerless don’t want,

nor she whoflees,chase (imperative), nor miserable live (imperative), but with obstinate mind carry on (imperative), be tough (imperative)!

“In the last line, obstinātā mente is in the ablative, but without a preposition. The words mean, ‘with an obstinate mind’, or ‘with mind made up’.”

Valē puella, iam Catullus obdūrat, nec tē requīret nec rogābit invītam.

,

norhe will seek back norunwilling (obj.).

“Notice that tē is the object, and it refers to Lesbia; and invītam is accusative, so it is she who is unwilling.”

At tū dolēbis, cum rogāberis nūlla. Scelesta, vae tē, quae tibi manet vīta?

But will feel pain,you will be askednever.

Bad woman, for you;what sort of ?

“The word quae goes with vīta, as both are nominative: ‘what sort of life?’”

Quis nunc tē adībit? Cui vidēberis bella? Quem nunc amābis? Cuius esse dīcēris? Quem bāsiābis? Cui labella mordēbis?

At tū, Catulle, dēstinātus obdūrā.

will go to? you will seempretty?

? will you be said?

you will kiss?lipsyou will gnaw?

But , ,determined (pred.) (imperative).

I don’t understand something: why does Catullus call Clodia Lesbia?

“‘Lesbia’ is Catullus’ name for Clodia in his poetry. By giving her a code-name, he could carry on the affair and write poems about it that circulated without getting into trouble. He chose ‘Lesbia’ as her name for two reasons. Many fans of poetry believe that of all the old Greek love poets, Sappho from the island of Lesbos was the best of all. Catullus himself translated Sappho into Latin – one translation that he made begins, Ille mī par esse deō vidētur, ‘That man seems to me to be equal to a god’. Now Lesbia in Latin means ‘woman from Lesbos’. So, by choosing that name it meant that he loved Clodia as much as he loved Sappho. The other reason for his choice is that ‘Lesbia’ has the same number of letters and syllables as ‘Clodia’: six, and three. That was the rule for picking a nickname in poetry.”

What happened to Clodia? What about her and Metellus?

“The full story is lost to time, but other poems of Catullus communicate that their marriage was rocky. Clodia had at least one more lover, a young man named Caelius, who was charged in court with attempted murder. He was defended by none other than Cicero. Cicero spent a good part of his speech, the Prō Caeliō, smearing Clodia’s reputation, to separate his client from her, and tried to make her seem like a prostitute. You can read the speech to find out more about her, but be careful – it’s all slander and smears. You can also read Catullus’ poems to and about her – but they are the work of love, hardly objective. Perhaps we can trust Catullus enough to believe that their love was indeed mutual, for a time, and sweet? But Clodia no longer has a voice, and not even the gods,” she added, shaking her head, “know what any human being truly feels in her heart, or his heart.”

- A Roman mosaic from the first-century CE showing two amātōrēs or lovers. Note the attendants, who are probably servī, enslaved persons, engaged in various tasks.

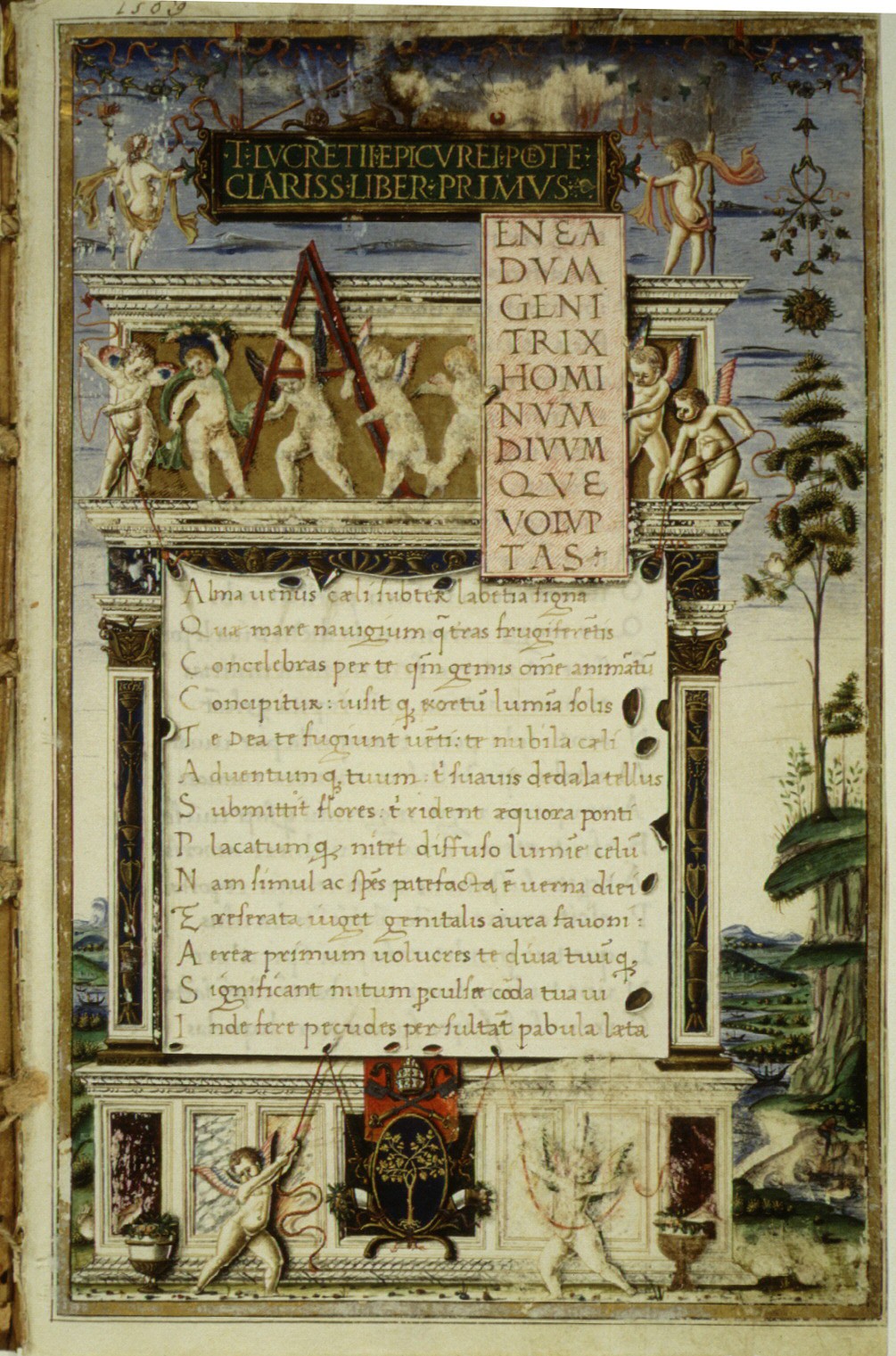

A manuscript, written in 1483, of Lucretius’ poem Dē Rērum Nātūrā. The title at the top reads T(itus) Lucretiī Epicūreī poēt(a)e clāriss(imī) liber prīmus, ‘Of Titus Lucretius the Epicurean, the most famous poet, the first book.’ The first line reads Aeneadum genetrix, hominum dīvumque voluptās, ‘Matriarch of the Aeneas family, pleasure of men and gods…’, referring to the goddess Venus.

A manuscript, written in 1483, of Lucretius’ poem Dē Rērum Nātūrā. The title at the top reads T(itus) Lucretiī Epicūreī poēt(a)e clāriss(imī) liber prīmus, ‘Of Titus Lucretius the Epicurean, the most famous poet, the first book.’ The first line reads Aeneadum genetrix, hominum dīvumque voluptās, ‘Matriarch of the Aeneas family, pleasure of men and gods…’, referring to the goddess Venus.