Kimberley Garcia and Rachael Benavidez

Narrative Levels

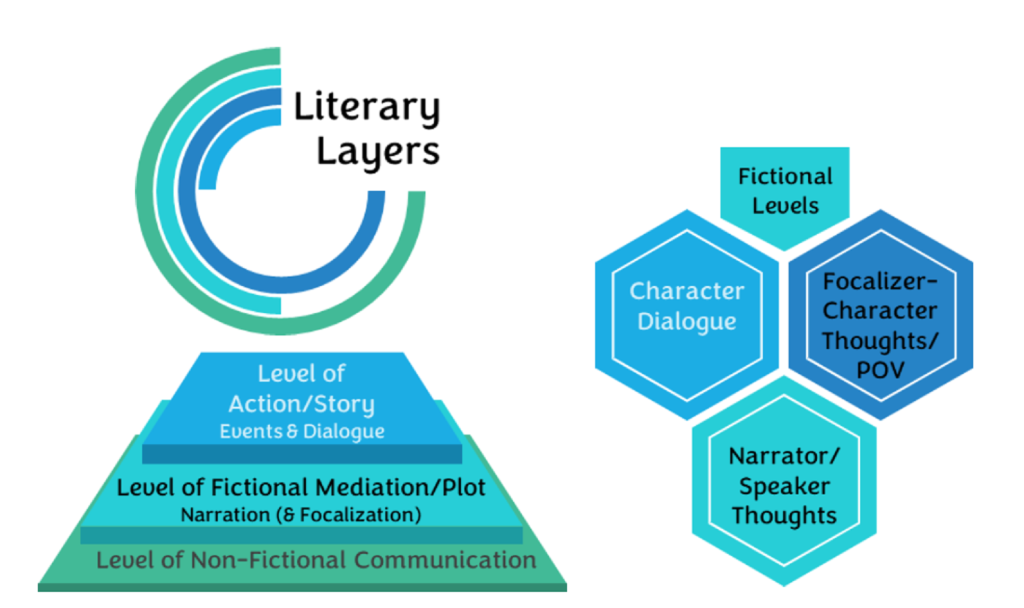

The layers of narrative distinguish the levels of awareness or knowledge in a given text and contain different discourses or communicated messages.

- Action Level: Story Events / Characters talking to Characters

- Mediation Level: Ordering / Narrator’s Discourse of the Fictional World

- Non-Fictional Level: Authorial Subtext / Author’s Messaging to the Reader

Story / Plot: Characters Within and Narrators Without

Any text that has arrangement or ordering fulfills the basic requirement of narrative. The ordering and relation of events, description, and dialogue is a mediating level between the character level and the reader’s level.

The strongest literary analyses will know to distinguish the character level from the mediation level and the mediation level from the non-fictional or authorial level.

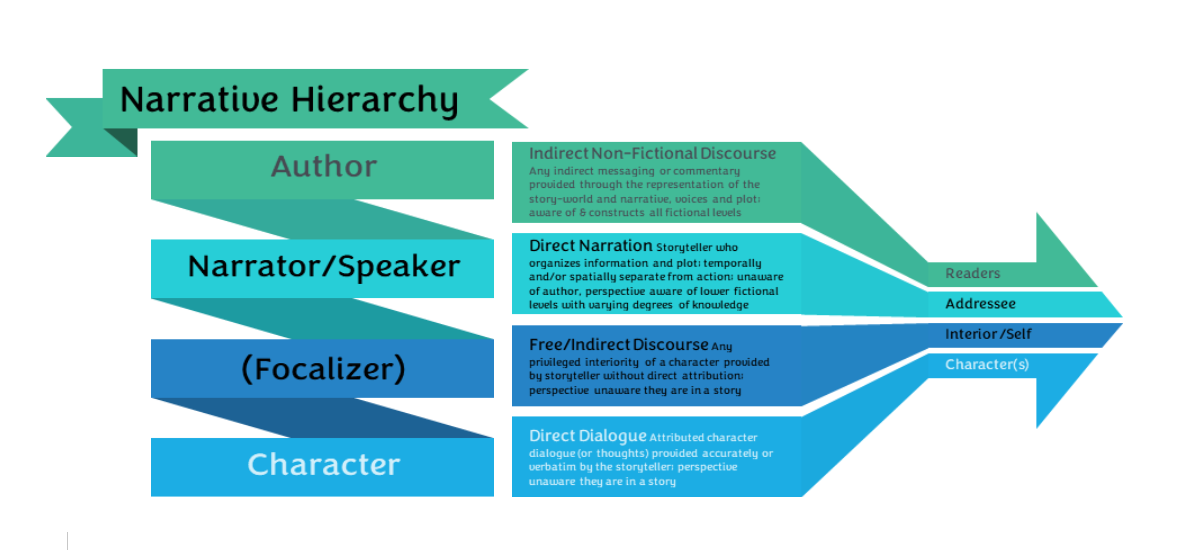

The mediating level has its own voice, whether narrator or poetic speaker, that is a deliberate construction of and distanced from the author. The mediating level has a level of knowledge, control, and awareness of the story events that is elevated from the characters. The characters do not know (typically) that they are within or part of a story. Sometime that narrator or speaker is also a character within the story events, or exists on the level of the story events, though they have more control and power over how the story presents to the reader. The narrator’s control and awareness of the events of the story allow them the power to organize the narrative or plotting to create effects on the audience.

The layers of representation–action and mediation–are the fictional discourses of literary works. The layer of authorial discourse, or non-fictional discourse, is only ever indirectly communicated through the layers of representation; in other words, the author never speaks directly to the reader. Any messaging the reader perceives from the author is indirect, operating through the representation and operation of the fiction or composition.

The Narrative Hierarchy

Typically the hierarchy of knowledge in narrative operates with each level unaware of the level above it (with more control, knowledge, or power). When a lower level becomes aware of the operations of a higher level, such as a character aware that there is a narrator or a viewing audience (by breaking the fourth wall), it is called metalepsis. In drama or film a character might speak directly to the audience, or a cartoon character fight with their animator’s hand. Any awareness by the constructed character of knowledge that they are a construction is a form of metalepsis. If a narrator addresses their reader, however, by suggesting an awareness of a reading audience, this is not necessarily metalepsis because the narrative level accounts for the narrator to perceive that there is a recipient for what they narrate–that recipient is often not identified (yet likely they are in epistolary form), though sometimes they are simply understood as posterity: many early novels represented their stories as “histories.” It would be metalepsis if a narrator acknowledges awareness of the author constructing them and the story.

Literary Layers (& Narrative Hierarchies) in Different Genres or Media Forms

Prose stories (such as novels, short stories, memoirs) often include apparent narrators that are distinct voices and persons from the characters in the story. Alternatively, the narrator might be a character in the story, though they might typically speak from an awareness or knowledge (and/or time and place) outside of the action, later and speak in the past tense. Often the mediation of the narrator is clear in this form of storytelling. Remember, the narrator is always a representation or constructed voice that is different from the author.

Drama, when not performed but read, includes written stage direction that operates similar to the description a narrator would provide. Some plays will include a narrating character that appears to provide context or commentary alongside but apart from the action of the characters and dialogue. It is important to recognize that any narrative agent (character or stage direction) is a representation or constructed voice that is different from the author.

Poetry may not always have an evident story in the strictest sense, though the layer of action (where other forms have dialogue and characters represented) corresponds to the content conveyed by the poetic speaker–the voice that presents the poem–rather than a narrator. Some poetry may include story, characters, and even an identified person as the poetic speaker. It remains important to recognize that the poetic speaker, as with a narrator, is a representation or constructed voice that is different from the poet or author.

Visual media (such as film, television, video games) maintains the same literary layers and narrative hierarchies as written literature. The level of action includes characters (whether playable or non-playable); the level of mediation includes any narrators (or focalizers) or narrative operation that organizes, provides, or withholds information; the level of author corresponds to the filmic composition device (such as a camera) that relates the story by arranging and controlling (such as mise-en-scène) narrative operations, the plot and story-world elements.