9 Chapter 9. Clauses

Matt Garley

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The clause is the largest unit of English syntax, and is a type of category, like phrases and parts of speech. In general, to analyze the syntax of an English sentence, we begin by labeling parts of speech, then organize those into phrases, which are further organized into clauses.

To review, main clauses (CL), sometimes called independent clauses, are generally the same thing we think of when we think of a ‘complete sentence’–that is, a sentence with a noun phrase (NP) or occasionally a subordinate clause (SC) functioning as the subject followed by a verb phrase (VP) functioning as the predicate. A common definition of these is a clause that ‘expresses a complete thought’–however, we should know by now to be wary of vague definitions like this. Checking for a subject and a predicate (plus a finite verb, which we’ll discuss later) is a better way to ensure that we have a main clause.

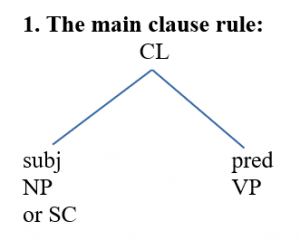

One way we can write the main clause rule is:

CL –> subj (NP or SC), pred (VP)

Or, using a tree structure, like this:

The subordinate clause rule.

(1) John went to the store.

[John] (NP subject) [went to the store] (VP predicate)

(2) Playing video games is my favorite pastime.

[Playing video games] (SC subject) [is my favorite pastime] (VP predicate)

There is one specific situation in which a complete sentence can contain more than one main clause: when two main clauses are coordinated into one, using a coordinator like and, but, or or:

(3) [The Department of Agriculture issued a warning], but [dozens of people got sick from the tainted spinach].

In (3), both of the bracketed pieces are complete sentences and main clauses on their own, but the coordinator rule, which takes two of the same category and makes them into one, means that they can go together as one main clause (and in writing, one complete sentence).

There is one other major category of clause beyond the main clause; this is the subordinate clause (SC). In this chapter, we will examine subordinate clauses and where they are used in syntax, along with specific subcategories of subordinate clause: relative clauses and finite vs. nonfinite clauses.

Subordinate Clauses

Subordinate clauses are also often known as dependent or embedded clauses. Many traditional grammars discuss subordinate clauses as dependent clauses, but we choose not to in this book, because it leads to confusion. In (4-6) below, the subordinate clause is placed in brackets:

(4) I know [I should have checked my bank account].

(5) I strongly believe [that the secretary embezzled funds].

(6) I really want [my car running reliably]

In (4), if the subordinate clause [I should have checked my bank account] were removed, it could stand as a sentence on its own. In (5), that’s almost the case, but the subordinator that makes it unacceptable as a sentence. In (6), [my car running reliably] would not be able to work independently. However, all of these are subordinate clauses–for that reason, we’ll drop the terms dependent and independent, and we’ll discuss the differences between (4-5) on the one hand and (6) on the other as the difference between finite (‘tensed’) and non-finite (‘untensed’) clauses later in this chapter.

Another set of terms used by a number of modern grammar texts is adverbial, adjectival, and nominal clauses. We will not use those terms in this class, as they refer to the function of the subordinate clause, which we have other terminology for. An ‘adverbial clause’ is simply a subordinate clause which has the same function as an adverb phrase; that is, as an adjunct of a VP, or as a modifier of an AdjP, AdvP, or PP. An ‘adjectival clause’ is a subordinate clause modifying an NP (we’ll call these relative clauses, which is more traditional). A ‘nominal clause’ is an SC acting as the subject of the sentence, as in (2) above, or acting as the complement of a VP or PP–because we separate category from function, we don’t need these specific terms, and we can recognize these as different functions of one category, subordinate clauses.

Remember that we can represent the main clause rule as:

CL –> subj (NP or SC), pred (VP)

A main clause always has a noun phrase or subordinate clause functioning as the subject, followed by one VP functioning as the predicate.

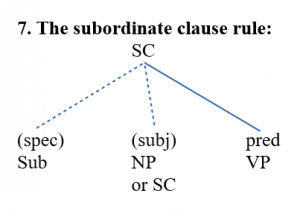

We can write a similar rule for the subordinate clause:

SC –> spec (Sub), subj (NP or SC), pred (VP)

Here, I’ve put the elements which are optional in italics. As you can see, there are two main differences between main clauses and subordinate clauses. First, subordinate clauses (like NPs and VPs) can sometimes have a specifier, which is in this case a subordinator (like who, which, that, because, since, if, whether). Remember that not every SC has a subordinator; this is important when trying to identify them. Note that sometimes, these subordinators are optional, as in (7a-b), but sometimes they are not, as in (7c-d)

(7a) I saw [that you called earlier].

(7b) I saw [you called earlier].

(7c) I wonder [if you called earlier].

(7d) *I wonder [you called earlier].

The second major difference is that, unlike main clauses, not all subordinate clauses feature an NP or SC subject. In fact, it’s possible to have no subject at all in a subordinate clause.

(8) The boss saw [the customer leave].

(9) The boss saw the customer [that left].

If we analyze (8), we see that [the customer leave] is an SC with no specifier, but a subject [the customer] and a predicate [leave]. In (9), however, the subordinator [that] indicates the beginning of the subordinate clause, but all we have is a predicate–[left] with no subject. Here, the subject is inferred to be ‘the customer’, but it does not actually appear in the subordinate clause.

This feature actually allows us to do a lot of interesting things in terms of analysis, like find explanations for sentences like (10), which appear to have two main verbs:

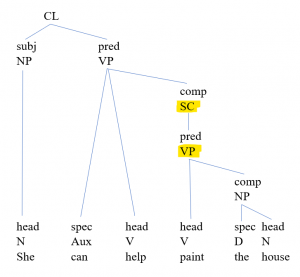

(10) She can help paint the house.

If we analyze [paint] as a V head of a VP, we can say that it’s a subordinate clause that only has a predicate [paint the house]; and that that subordinate clause is the complement of the VP in the main clause headed by ‘help’.

Relative Clauses

Adapted by Matt Garley from work by Jodiann Samuels, Ilvea Lezama, and two anonymous ENG 270 students.

A relative clause is a specific kind of subordinate clause that modifies a noun or noun phrase. However, there are two types of relative clauses: restrictive and non-restrictive relative clauses.

the relative subordinate clause can be introduced by a special kind of subordinator called a relative pronoun (which we should remember is not labeled as a pronoun in our system, but rather as a subordinator) (i.e., who, whom, which, that, where, when). Relative pronouns, like other subordinators, are sometimes optional, but sometimes necessary to express the meaning of the subordinate clause–in the following examples, relative clauses are in brackets:

(11a) The car [that my aunt bought] is nice.

(11b) The car [my aunt bought] is nice.

(11c) The woman [who wears the burgundy dress] is nice.

(11d) *The woman [wears the burgundy dress] is nice.

In (11a-c) we have relative clauses modifying the car and the woman which have (11a and 11c) and lack (11b) relative pronouns; however, (11d) without a relative pronoun does not work.

However, what makes the relative clause identifiable is not that it is introduced by a relative pronoun but that it modifies a noun phrase. (Benner, n.d.; Huddleston & Pullum, 2005, p. 21, 25, 183).

Restrictive and non-restrictive relative clauses

A restrictive relative clause gives important information about the noun that comes before this clause (Lexico 1). When you see this type of clause, it is usually introduced with words like, that, which, or who. Sometimes the meaning of the sentence stays the same with or without these two words. Also, you do not need to use commas with this clause.

(12) He took the ball [that was deflated].

(13a) My nails [that I painted yesterday] are red.

A non-restrictive relative clause (sometimes called an appositive relative clause) is the opposite of a restrictive clause. This is information that could be left out of a sentence without affecting its meaning (Lexico 1). It is your choice to add the extra information or not.

(14) She bought a book for herself [which she could not wait to read].

If you take out the second part of the sentence, the meaning would still stay the same which is that the subject of the sentence bought a book for herself. However, non-restrictive relative clauses can be positioned in the middle of a sentence. When this happens, a comma goes on both sides of this clause.

(15) Michelle, [who opened the door aggressively], hit the old man in the back.

(13b) My nails, [that I painted yesterday], are red.

If you examine the difference in meaning between (13a) and (13b), we can see more clearly the difference between restrictive and non-restrictive relative clauses. In (13b), all of the speaker’s nails are painted red. In (13a), there’s room for the interpretation that only some of the speaker’s nails were painted yesterday, and only those nails are red (with other nails possibly being other colors, and having been painted at another time).

Finite and non-finite clauses

Adapted by Matt Garley from work by Gurpreet Kaur and an anonlymous ENG 270 student

Non-finite clauses are subordinate clauses which contain secondary (‘non-finite’) verb forms, including participles, gerunds, and infinitives (Huddleston & Pullum 205). Non-finite clauses are often used when the subject is the same as the subject in the main clause. In addition, sometimes non-finite clauses have no subject when they function as adjuncts, which can make them hard to understand. With respect to the discussion of the terms ‘independent’ and ‘dependent’ clauses earlier, non-finite clauses are truly dependent, as they do not carry tense and thus cannot function as main clauses, even when taken out of their clausal context. Non-finite verbs o not indicate tense because “the verb or auxiliary carrying tense is called finite, all other forms (nontensed) are called non-finite (not restricted in terms of tense, person, and number)” (Brinton & Brinton 225).

What are the four verb forms that appear in Non-Finite Clauses?

The four verb forms that appear in Non-finite clauses, can be known as, to-infinitivals, bare infinitives, participles (called past participles in other texts) and gerunds (called gerund-participles in other texts) (Huddleston & Pullum 204).

| Construction | Example | Verb Form Required |

| To-infinitival | to draw a portrait | plain form (introduced with particle to) |

| bare infinitival | draw a portrait | plain form |

| gerund | drawing a portrait | gerund |

| participial | drawn a portrait | participle |

(Adapted from Pullum, “Non-finite Clauses”)

To-infinitivals can function as subjects (16) and complements (17) of the VP:

(16) [To err] is human.

(17) I really want [to go on vacation]

They can also function as adjuncts and modifiers as well in a number of constructions that includes, subject, extraposed subject, extraposed object, internal comp of verb, comp of preposition, adjunct in clause, comp of noun, modifier in NP, comp of adjective and indirect comp. Each will contain “to” in the sentence, but some of these complements and modifiers can be in the beginning of the sentence while some at the end of the sentence (Aljović 35).

Unlike to-infinitivals, bare infinitivals only appear in very few functions. They occur in the function of complements of certain verbs, with no subject.

Some examples:

(18) Can you help him do his homework? [complement of modal auxiliary],

(19) I want you to help me clean up the bedroom [complement of help],

(20) We didn’t see them walk in the street, [complement of make, let, see, etc.] (Aljović 36),

(21) All I did was close the book [complement of specifying be].

Participial non-finite clauses have two functions: internal comp of verb and modifier in NP. As a modifier, participials form a special kind of passive (Huddleston, Pullum 214). Finally, gerund non-finite clauses share some similar functions as to-infinitivials.

Omissions from non-finite clauses

Non-finite clauses do not make complete sentences as they often don’t have a subject or direct object (Brinton & Brinton 275). Usually when the subject is the same as the main subject, the subject of the non-finite clause is omitted. This can also be because non-finite clauses that are dependent and when they are linked with independent clauses which leads the subject to become omitted. When the subject becomes omitted, the process is called “ellipsis”.

References

-

Aljovic, Nadira. Non-Finite Clauses in English Properties and Function. 2017, www.researchgate.net/publication/319269617_Non-finite_Clauses_in_English_Properties_and_Function.

-

Benner, Margaret L. “ Adverbial, Adjectival, Nominal.” Dependent Clauses, Towson University, webapps.towson.edu/ows/advadjnomclause.htm.

- Brinton, Laurel J. and Brinton, Donna M. The Linguistic Structure of Modern English. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Edition 2. July 2010.

- Fox, Barbara A., and Sandra A. Thompson. “A Discourse Explanation of the Grammar of Relative Clauses in English Conversation.” Language, vol. 66, no. 2, Linguistic Society of

America, 1990, pp. 297–316, https://doi.org/10.2307/414888 -

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey K Pullum. A Student’s Introduction to English Grammar. 2005.

-

Lexico. “What Are the Types of Different Clauses?” https://www.lexico.com/grammar/clauses. Accessed 30 November 2020.

- Pullum, Geoffrey K. “Non-finite clauses” http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/~gpullum/grammar/nonfiniteclauses.html