9 Narration

Narratives

What is it about cinema that transcends the barriers of nationality, ethnicity, and language, at its best revealing a shared humanity despite our differences? Every culture tells stories. From the earliest oral traditions to contemporary forms of social media, stories have been used to entertain, educate and stimulate the emotions. Few of us have grown up without hearing bedtime stories and moral tales like the Good Samaritan or comedic anecdotes from friends to explain an unexpected situation or horrendous breakup. Storytelling pervades every aspect of life and provides a means of understanding self and world. Whether we go to the movies or sit at home in front of the computer, when we watch films, image and sound come together in visceral and subjective ways. Despite our respective backgrounds, we experience the story world from the same point of view, through the same empathetic or dispassionate lens. Of course, this does not mean we will always understand or feel the same things when we watch a film, only that cinema uses unique techniques on all spectators to help follow its storytelling and also to manipulate the minds and emotions. When we watch films, image and sound come together in visceral and subjective ways.

Narrative film is one of the most popular and common forms of cinema, and in its broadest terms can be understood as fiction films with a particular structure that tells a story. Classical Hollywood narrative cinema is the most powerful and pervasive style of this filmmaking. It characterized American cinema from 1917 to 1960 and remains the dominant approach to visual storytelling worldwide. Through a focus on invisibility and continuity (see Ch 5: Editing), the Classical Hollywood approach to filmmaking hides the artificiality of the medium, convincing audiences that they are watching something real, not pieces of film sutured together by filmmakers. In this way, Classical Hollywood cinema is marked by its assumed realism and rational linear narrative centered on the psychological motivation of its characters as they struggle to overcome the obstacles set before them.

Every film has a shape or a form that dictates how the content of a film is presented both narratively and stylistically. For example, you might think about beginnings and endings. All stories have a beginning and an end, but an end can be open, where we are left with uncertainty for the future of characters, or it can be closed with a clear resolution to events. Similarly, a film can begin at the end of a hero’s journey rather than at the start, challenging how the sequence of narrative events will be visually presented. In Cinema Paradiso (Tornatore, 1988), audiences are introduced to successful filmmaker Salvatore Di Vita who arrives home late one evening to the news that his mother called to say someone named Alfredo had died. But who is Alfredo? And why has his death deeply shaken our protagonist? With Alfredo’s death, Salvatore returns home to Sicily first in memory, in an extended flashback sequence, and then in person as an adult in the present to say goodbye and gain closure after an absence of thirty years. In the Classical Hollywood narrative style, the flashback is one of the only ways that straightforward linear structure can be undermined in cinema, typically through visualization of a character’s memory.

Director Giuseppe Tornatore could have shaped his film in many different ways. He could have begun his film in a chronological fashion, with Salvatore (called Toto) as a child growing up and finding love in his home village of Giancaldo, Sicily. You could also imagine a scenario where the film begins with an adult Salvatore learning of Alfredo’s death and immediately returning to his hometown where he must face the specters of his past in real time as an adult. Instead, Tornatore uses aural triggers of bells and chimes to move back and forth in time as Salvatore relives his childhood and remembers the deeply parental relationship between himself and Alfredo. Rather than the conventional shape of beginning, middle, and end, with a clear resolution often characteristic of Classical Hollywood Cinema, Cinema Paradiso takes on the structure of memory. The narrative takes place mostly in the past. The director frames his film with an adult Toto remembering the love and loss of his youth until we eventually circle fully back to the present to an adult Toto who must make peace with his ghosts. In all of these different ways to organize the telling of Toto’s life, the story remains the same: Toto finds love and mentorship in the past and remembers it in the present. But in each strategy of telling the same story, the plot changes. The plot is the arrangement of the story elements. In this case, the story begins in the present but takes place largely in the past, moving back and forth between past and the present. Even when stories appear to move across different timelines, these timelines all must move forward through time towards some goal or big reveal that the narrative is dependent upon.

You might have noticed that I have been using the term ‘narrative’ but what exactly is narrative? Narrative presents the story world in specific ways for our consumption. It is the whole storytelling system of a film composed of story, plot and narration, as well as the film’s structural elements of similarities, oppositions, and repetitions that guide audience understanding of the film and its patterns. Often when we think of narrative it is a literary text that comes to mind rather than a film. It is helpful to think of films as texts that display an unfolding of causal events in time and space. A narrative is not a random chain of events, but, through character action and reactions (the cause) that prompt an effect or response from others, characters propel a film’s story forward. In Classical Hollywood cinema, for example, film form adopts a causal narrative, where everything is a result of a certain action, thus creating logical and often predictable outcomes.

Key Terms

Narrative film: A fictional or fictionalized story. As opposed to documentaries (non-narrative films).

Classical Hollywood narrative: A specific storytelling structure developed in early American cinema that has become the norm for narrative film. Includes elements like the three-act structure, causal relationships between events, clear character motivation, and often, a closed ending.

Open ending: The film intentionally leaves the audience uncertain about the future of characters.

Closed ending: The film ends with a clear resolution to story events.

Causal narrative: Story events progress in a cause-and-effect relationship. Every event is the cause of a certain action, often creating predictable outcomes. There is little room for randomness or non-sequiturs in these narratives.

Story, plot, and narration

Story, plot, and narration can be difficult concepts to grasp, as they are often nested within each other, and the terms are used interchangeably in popular culture. Story presents the film’s diegesis: a story world in which things both seen and unseen (also heard) give insights into how characters think and the rules by which the world functions. Narration points to where the story emerges from, that is, from whose perspective the story is being told. It is often caught up in camera perspectives, point of view gazing and authorial voiceovers. As mentioned earlier, plot, on the other hand, is the arrangement of the story in time. These three important modes of a film (story, plot and narration) occur all the time and make up a narrative system through which audiences intuit meaning. In most films, we are often asked to identify with a protagonist or characters who lie at the center of the story. Narrative is important to understand a character’s motivation, their place in the story world, and their growth and change throughout a film. Narrative introduces characters and directs us through impressions of their character.

For example, in Cinema Paradiso, the story is about a famous filmmaker who learns that his old mentor has died and remembers his days spent within the walls of the movie house Cinema Paradiso while he developed an enduring relationship with the middle-aged projectionist, Alfredo. But we learn more about Toto’s life than just the direct facts of the story. We also build our understanding of story from events that occur off-screen, that we learn third-hand or that grow out of purely visual moments like flashbacks and nonverbal cues. These additional levels of story create viewing excitement because they ask us to play detective and to read deeper into the film, much like analyzing a text. Six-year-old Toto learns of his father’s death from watching a newsreel playing at the Cinema Paradiso. The director cuts to Toto walking with his sobbing mother but instead of succumbing to grief himself Toto smiles at a poster of famous film star Clark Gable on a wall as he passes by. We can understand several things in this moment. Although we never see Toto running to tell his mother the news of his father’s death, this gap is filled by our deduction of the missing pieces to the story. In this way, the audience becomes a type of narrator and both imagines the unseen that has happened, in a fleshing out of the story, and composes meaning that deepens character insight and motivation. By reading the shot/reverse-shot editing between Toto and Clark Gable, utilized in the midst of Toto’s grappling with the death of a father he does not remember, the spectator understands that Toto is blurring his father with Clark Gable. The story of Cinema Paradiso then is not simply one of a man who returns to his past to find closure, but a love story that emerges out of loss, where both cinema and Alfredo become parental and life substitutes for Toto.

Key Terms

Story: A series of events that form the building blocks of narrative.

Diegesis: A story world within which characters live and interact with its own set of rules and customs. Includes what is seen in the frame and also what exists beyond the edges of the frame that characters react to.

Plot: The arrangement of story elements in time. Events can be organized chronologically or told out of temporal order.

Book excerpt provided by Michael Wiese.

Productions from Crash! Boom! Bang! How to Write Action Movies by Michael Lucker.

Three-Act Structure

All stories are broken into three acts: a beginning, middle, and an end. That’s it. Try to drop one of them and the story falls apart. The beginning is the introduction where you introduce everyone and everything you need to set your story in motion. This is Act One. The middle is the complication where you complicate everything you already set up. This is Act Two. The end is the resolution where you resolve everything you complicated earlier. Act Three. Easy peasy, right? But good act structure is often tossed asunder.

The beginning, middle, and end of your story are all separated by what are known as plot points. These are major twists that propel your hero from one act to the next, forcing them to make new decisions. The best plot points alter the course of the story in a way neither the hero nor the audience was expecting. Ideally, they drop the hero into a predicament from which they cannot return. If a hero loses his phone, no big deal, he goes back and finds it. Bad plot point. If a hero loses his job, or his leg, or his virginity, tougher to fix. Good plot point. These unforseen turns should not only complicate matters for the hero, but also raise the stakes, that which is at risk of being gained or lost.

In action films, plot points must be extraordinary. The genre itself implies action and plot points must deliver it. Something must blow up. Someone must get robbed. Somewhere people die. Lies and threats and thefts can all be solid twists in action films, but the good ones literally propell your hero forward. Through the air. Through a wall. Or through time. That is the fix action audiences are accustomed to getting.

Plato, Shakespeare, Hitchcock, Spielberg, Tarantino all have plot points in their work. Because they work. Because we’re wanting something to happen. We’re wanting progress. In screenplays, one page is equal to one minute of screen time. So a two-hour movie (120 minutes) is 120 pages. A three-act structure breaks down like this:

Plot Point I: between pages 25 & 30

Plot Point II: between pages 85 & 90

But that leaves a dark and murky sea between them of almost sixty pages. In the old days, filmmakers could get away with those few twists. But not today. We’re used to getting much more much quicker and need a Midpoint Plot Point around page 60 to bridge the gap. James Cameron says he writes in seven acts. Something that turns your hero’s life upside down in an instant and forces them to make a new decision.

The Call to Action

Every action hero is called to action. We meet them set in their dysfunctional ways in their dysfunctional world. Then someone calls. Someone walks in the door. A letter is delivered. With a mission.

Indiana Jones, we need you to find an ark.

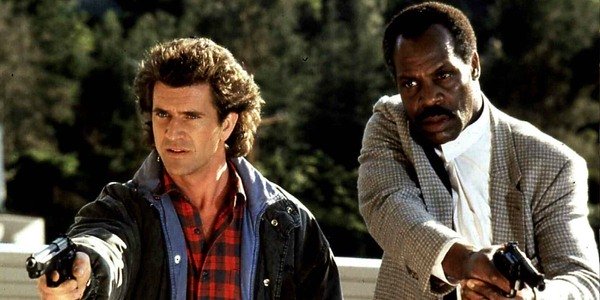

Detective Riggs, we need you to find a killer.

Ethan Hunt, your mission, should you choose to accept it, find the rabbit’s foot.

This is what’s known as the inciting incident of the story and falls around the tenth minute. If you wait much longer, the audience gets antsy.

High Stakes

What is your hero fighting for? For your hero to go to the ends of the earth, face the fire, and risk everything they have in order to get tickets to the opera seems, well, ridiculous. In action films, you want your hero’s quest to be worthwhile. Of course, there could be great rewards for their success, but also consider what the consequences of failure may be:

Their fiance may be killed.

Their daughter could be kidnapped.

The president could be assassinated.

Aliens may destroy the world.

In all movies, stakes should elevate as the story progresses. But it is imperative in action movies. For example, in the beginning your hero may learn someone has been killed and he is assigned to find the killer. The stakes? If he doesn’t find the killer, the crime goes unpunished, the person died in vain, and the killer is free to kill again. That is pretty significant.

Georgia Filmmaker &

Screenwriting lecturer

University of North Georgia

Key Terms

Narration: The subjective telling of story from a specific point of view. This point of view can be seen in plot organization, in a voiceover, and in cinematography, editing, or mise-en-scène choices.

Off-screen: Events that occur beyond the film frame provided to the viewers. These events are in the diegesis and characters may have access to them, but viewers must learn of off-screen events by deduction.

Narrators

Cinema has the unique ability to tell its stories aesthetically, through the use of close-ups, music, lighting, the framing of on-screen and off-screen space, even dance and pantomime. Gazing in particular is distinctly filmic and a central means of narration in cinema. Cinema always presupposes a narration, a story being told by someone even when there is not an actual narrator. To perceive the narrator of any film, one must ask the question: from whose perspective is this story being told? The narration in Cinema Paradiso is from Toto’s point of view and told via flashbacks, but even when we are in the present with an adult Toto, the camera lets us know that his story is the one that is privileged through framing, close-ups and eyeline matches that follow the character and keep us close to his body and his psychology. Often when we imagine the narrator of a film, we think of either a physical character within the diegesis who relates the order of events and guides us through the film, or a non-character, someone unseen who speaks in voiceover and assumes the position of authority in the text. But not all narrators fall cleanly into these two categories; many films mix a voiceover with a subjective point of view to tell a story. Tarsem Singh’s fantasy film, The Fall (2006), frames narrative as a story being told to a little girl named Alexandria, by Roy, a depressed silent film stunt actor, who wishes to manipulate her into helping him to kill himself. Voiceover brings emphasis and clarity to a film’s mise-en-scène and story development, aiding in continuity and the structure of the filmic text. The Fall thus adopts a story-within-a-story structure and positions its voiceover narrator as a character within the film, moving between Roy’s oral tale and Alexandria’s visualization of the story.

An interesting development occurs in The Fall as Roy narrates his tale, and Alexandria frequently interrupts its telling. Alexandria begins to move from mere listener-spectator of the story to replace Roy as storyteller. Although initially Roy narrates the story, it is the listener’s voice which begins to take over the frame’s point of view or subjectivity. Alexandria’s voiceover and sight is privileged alongside Roy’s as storyteller. She is able to re-imagine the look of characters based on events from her own life and, ultimately, change the course of events at the end of the film by adding herself as a character to the story.

For the non-character voiceover narrator, who is historically male, there is an understanding that he has full knowledge of the events that will unfold, unlike the film’s characters who are caught in the story’s web and so have limited knowledge. In this way, the non-character narrator often is considered a ‘voice of God’, even though the commentator may lack objectivity. In The Truman Show (1998) director Peter Weir plays with audience understanding of the voiceover narrator as God. Starring Jim Carrey as Truman Burbank, The Truman Show is about a child adopted and raised by a corporation who grows to adulthood inside a popular simulated television show based on his life. As an adult, Truman grows to be aware of the artificiality of his life and seeks to escape the fantasy on-screen bubble in which he lives. At the end of the film, Christof, the show’s creator and executive producer, attempts to convince Truman to stay by speaking to him anonymously through a speaker system. For Truman, in his artificial story world, Christof’s voice takes on the appearance of God in its disembodiment and absolute knowledge of characters and events within the diegesis. And yet, this voiceover narrator stills holds limited knowledge of the interiority of characters, and he cannot fully predict the choices that characters make within the story. Christof cannot control Truman’s actions, even though he can manipulate the artificial world, and he is surprised by Truman’s final decision to leave the bubble.

The voiceover narrator is also often used as a fountain of information to relay past events and deepen the emotional nuance of a story. Non-character voiceover narrations are typically understood as non-diegetic, since the narration originates from outside the film’s story world. Some films choose to reveal the non-character narrator as a character at some impactful point of the film’s narration. These films shift the narrator from non-diegetic to diegetic, with the intention of shocking audiences and advancing plot. Sunset Boulevard (Wilder, 1950), for example, presents its story about a forgotten silent film star’s desperate attempt to return to the movies from the point of view of a dead screenwriter found in the pool of the aging starlet. The film opens with a flash-forward and the voiceover narration of a man surprisingly revealed as dead within the first few minutes of the film, prompting the audience’s need to discover what happened as the film flashes back to the very beginning. Between 1950 and now, many films have repeated the dead-narrator voiceover technique made famous by Sunset Boulevard. One of the more successful examples is Sam Mendes’ American Beauty (1999) whose voiceover narrator, Burnham, is an advertising executive in the midst of a midlife crisis. Unlike Sunset Boulevard, American Beauty begins in the present and creates the illusion of a simple linear narrative in time and space. The film’s end shockingly discloses that the narrator has been dead all along, deepening the impact of American Beauty as a cautionary tale and as an exploration of American middle-class family values.

Female Narration

As mentioned earlier, voiceover narrators are typically gendered male in mainstream cinema, tapping into social assumptions of authority, knowledge and truth as male-centered attributes. The presence of a female narrator can point to, and challenge, such unconscious stereotypes and biases, allowing for female expression and perspectives. It would be in the so-called “woman’s films” or melodrama of the 1940s where a plethora of first-person female narrators would arise only to find their voices often undermined by the authority of men within the text. As originally articulated by feminist film critic Laura Mulvey, in Classical Hollywood Cinema the gaze of cinema is male. You might think here of a classic story pattern where a male hero engages in an epic struggle against a clever villain or antagonist and at some point, inevitably, rescues his love interest—the quintessential damsel in distress—from his enemy’s clutches to win day. Often we assume the point of view of the protagonist. His subjective understanding of the world becomes our own. Women are often presented as the object of a male gaze to be viewed from his perspective, not her own, which has been a difficult obstacle to overcome in female storytelling.

The Piano (Campion, 1993) stands as a unique film for its mute female protagonist, Ada, who controls the film’s voiceover, and also for its female authorship. Director Jane Campion wrote the screenplay for The Piano, providing a re-imagining of Emily Brontë’s 19th century novel Wuthering Heights, also authored by a female writer, and incorporating the theme of dangerous female gazing through its narrative and aesthetic staging of the Bluebeard folktale. Ada’s muteness sets up a politics of female resistance to patriarchal language and structures that seek to contain and disempower female voice and sexuality. The Piano begins immediately in female voiceover over a black screen, before image, as Ada narrates her background, privileging the use of a woman’s voice as narrator over the male gaze of the camera, and highlighting the inherent power of the female author and historian. Rather than have her story told by third parties or be constructed by a male ‘God’ narrator, Ada tells her own story, possessed of the ability to define her own self. Campion subverts the patriarchal mechanism of cinema, which typically privileges male voice and gazing as center of the story action, to situate Ada in a position of power as storyteller.

When a film has a narrator we often assume the reliability of the narrator, that the story they tell must be the truth, but films can also have unreliable narrators with compromised memories or who blur the truth. As we watch Toto grow into a young man in Cinema Paradiso, for instance, he falls in love with a beautiful young girl called Elena from an upper class family. But is Elena real, or is she only a figment of his imagination? Through the use of close-ups and reaction shots, the audience is constantly kept within Toto’s emotional frame of reference, and often when we see Elena, her presence is mediated through cinema and the movie camera in some way. For example, Elena is never seen outside of Toto’s point of view. The first time he sees her is through the eye of his home movie camera, and their secret meetings together typically occur in places of cinema or in his memory. One hot summer night at an outside film screening, Toto laments a rotten summer away from Elena and muses that if his love-affair were a film it would already be over, fade-out, cut to storm. Immediately thunder sounds and lighting strikes as rain begins to fall. The theme music swells as Elena suddenly appears within the close shot frame of Toto, and the two kiss. The improbability of the moment positions Toto’s relationship with Elena as one born out of cinematic fantasy, and it reveals Toto’s narration of the past as subjective, and thus compromised.

Key Terms

Narrator: The character or characters from whose point of view the story is told. The character(s) may be on-screen or off-screen; they may be diegetic or non-diegetic.

Voiceover: The voice of a character layered over the film image. This voice may be an omniscient perspec-tive or an inner voice. Voiceovers most often are associated with the film’s narrator.

Non-diegetic: Elements that exist outside of the diegesis, or story world. Characters in the story cannot see or hear non-diegetic elements, for example credits, subtitles, or orchestra music. When a narrator is non-diegetic, they exist outside of the diegesis and characters on screen are not aware that he is speaking.

Unreliable narrator: Narrators who defy our expectation the be told the “true” story. Unreliable narrators have compromised memories, intentionally blur the truth, or straight out lie to the viewer.

The Rashomon Effect and experiments in time

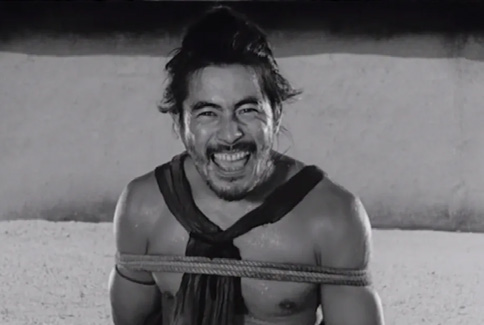

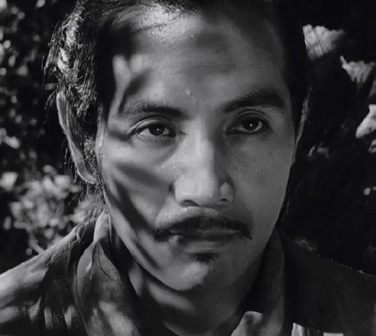

All acts of storytelling represent a perspective, and as such can never be truly objective. Some films structure their form around the very unreliability of the narrator. Storytelling presupposes the telling of tales or lies, and directors can play with audience expectations of a narrator’s truth-speaking to delve into deeper political and socio-cultural issues of nation and identity. In 1950, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon broke storytelling conventions with its revolutionary structure, which repeated the same dramatic incident from four different character perspectives: the samurai’s, his wife’s, the bandit Tajōmaru’s, and the woodcutter’s. What happens in the grove remains a mystery that leaves the samurai dead (and his story told through a psychic), his wife raped, and the murderer in question. At their trial, all four individuals give contradictory versions of the event in flashback sequences that privilege each individual narrator, presenting that storyteller in a more positive or sympathetic point of view than the rest. In one version of events, the bandit is a stud; in another, the husband is betrayed by his wife; in another, the wife is a childlike victim; and in another the woodcutter is an innocent bystander. Each story preserves a certain self-image that valorizes the individual and explores the ideas of memory and identity. Rashomon never resolves the whodunit mystery of its plot with its series of unreliable narrators, leaving its audience uncertain of what is truth, and both hopeful and untrusting of human nature.

Since Rashomon, many films have repurposed its unique storytelling structure that examines the unreliability of the narrator. Park Chan-Wook’s Joint Security Area (2000) adopts the Rashomon effect in the story of two North Korean and two South Korean soldiers who cross the divide, secretly forming a friendship in a small North Korean border house. The brotherhood formed between these four men presents an imagined community of a united Korea, but one night something happens in the border house that triggers fear and violence, leaving two men dead. The hope of a united Korea finds itself overwhelmed by power dynamics and the webs of cultural expectations about the ‘other’. The hunt to solve the mystery and stop an international incident between the two Koreas finds itself frustrated by conflicting witness accounts. Why would these soldiers tell two different versions of events? As with Rashomon, Joint Security Area is composed of flashback sequences as the survivors narrate their stories, and a neutral party seeks to parse out the truth. Unlike Rashomon, Joint Security Area shares the ‘true’ story at the film’s conclusion in a dossier that will never be shared with the North and South Korean governments and superior officers.

The audience alone is privileged with this final story and made to understand why these soldiers feel the need to tell stories. In its literal traversing of borders between self and other, often utilizing storytelling vehicles like the photograph, song, or memoir, the film questions the ‘truth’ of a conflict learned secondhand, the line separating vilified other from civilized self, the impossibility of neutrality or bridging the gap, and stresses the necessity of alternative modes of representation. Storytelling is politicized in Joint Security Area as the ordinary man must tell stories in order to survive in a world of uneven power dynamics, a world of division where the South Korean self is defined against the North Korean other. The theme of storytelling also reveals the similarity between the South and North Koreans and so humanizes the previously demonized North Korean Other, particularly by positioning two popular South Korean actors as North Koreans in the film.

Storytelling acts as an accessible and comfortable technique to address the present by constantly looking backwards and putting narrativity itself into question. Characters tell and retell stories as truth becomes a fluid and contradictory construct that time and distance only complicates and deepens. The audience is forced to adopt the role of investigator, with understanding growing the more a story finds itself retold, revised, and extended. One effect of these narrators who deliberately withhold ‘truth’ from the spectator is the shattering of the suspension of disbelief, which allows the spectator to sink into film narratives without questioning the reality before them. The Rashomon Effect disallows escape into the typical linear expectations of classical film narrative with its closed endings, calling forth a thinking spectator with no easy moral resolutions. While story and narration share points of intersection, it is important to note the distinction between the two. As The Rashomon Effect illustrates, story has a whole life separate from narration, and thus can be told in different ways by different narrators who experience the story event from different emotional standpoints and with different motivations.

The flow of information in narration is typically understood as being either restricted or unrestricted. When information is restricted in a film, both the character and the audience are given access to similar story information, and thereby learn and come to conclusions at roughly the same time. Unrestricted information, as the name suggests, privileges the audience with more knowledge than characters, both visually and aurally. For example, in M (Lang, 1931), a serial killer who preys on young children is identified to the audience only by the tune he whistles before he murders them. Imagine a scenario in this story world where a kindly non-descript man approaches a child and begins to whistle as he buys her a balloon and walks away with her. While the character is unaware that she is in the hands of a killer, the audience has been given access to this unrestricted information through the use of an aural cue, creating intense suspense as we helplessly watch, knowing what will happen. Later in the same film, the old blind man, who had previously sold the balloon to the little girl’s murderer, hears the whistled tune and recognizes the presence of the serial killer – now the narrative turns to restricted information. The audience in this moment does not know more than the old man in terms of the killer. Can characters know more than the audience? Such an idea introduces another way in which information flows in narration, where knowledge is deliberately withheld from the audience but accessible to characters in order to shock and surprise. Films move between different types of information flows at all times constantly working to manipulate their audiences’ investment in the narrative.

All stories are an experimentation in time. A story may be arranged in or out of chronological order. The duration time over which the story unfolds can be a few hours, a day, several years or centuries (think here, for instance, of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), which follows a vampire’s love story across time immemorial). The duration of a film can be extended and slowed in order to have audiences linger on a moment or pick up on subtler cues. Or, the film can be shortened through editing and ellipses to quicken the pace and excitement of the film. A story may also be told multiple times in a film, as in Rashomon, or a shot may be repeated by plot even though it only takes place once in the story. The amount of times the story or shot recurs in a film refers to its temporal frequency. Frequency can point to character psychology by indicating a repeated dream or memory, or it may simply create a pause in the film for audience introspection.

Every scene serves a particular function to cue the spectator into the film’s meaning. Meaning can be explicit, that is, on the surface, emerging as plot summaries or a description of what exists directly before our eyes and ears. But meaning can also be implicit or beneath the surface, which requires an active spectator to read, not just watch, the filmic text to uncover the deeper implications of the narrative. Motifs are particularly important as a stylistic technique often used in cinema to nonverbally enhance the meaning in a film. A motif refers to any significant element of a film that is repeated to deepen narrative meaning. A motif can be aural, like the whistling in M or the use of ringing bells to send the spectator spiraling through time in Cinema Paradiso. It can be a color, for example the repeated use of red in a film to signal budding rage and resistance. Motifs can be objects, settings, camera angles or a particular lighting, character, or camera movement. It really depends on the needs of the particular film and its individual style. Narration is human interaction, through which we communicate our thoughts, dreams, ideas and imaginings with one another. It can be spoken dialogue, gestures, and expressions, or a stream of visual images, sound, and music without characters saying a single word. As audiences we intuitively read the narrative system that structures a film in an attempt to perceive the larger point or argument that lies at the heart of every story.

Key Terms

The Rashomon Effect: A term used to describe the unreliability of eyewitness accounts. Based on the film Rashomon (Kurosawa, 1950).

Restricted narration: Both the protagonist and the audience are given access to the same story informa-tion.

Unrestricted narration: The audience knows more information than the protagonist. Often used to evoke suspense in narrative progression.

Temporal frequency: The amount of times that an event or shot recurs in a film.

Implicit meaning: Story meaning that is not given directly to the viewer, but is hidden and needs active interpretation to unpack.

Motif: Any significant element of a film that is repeated to deepen narrative meaning.

This chapter is adapted from FILM APPRECIATION by Dr. Yelizaveta Moss and Dr. Candice Wilson.