10 Sound

Sound

An audience can only look at one picture at a time, but it can hear many different sounds all at once. Amazingly, we can judge the weight, gender, and directionality of someone walking near us just by the sound of their footsteps. We tend to think of listening as musical attention, during which we care about loudness, pitch, or tone. But everyday listening – where we care about the source of sound, its cause, and its meaning to us – is crucially important to human experience and to sound design in film. The human perceptual system relies on sound for many of its functions: spatial orientation, judging danger or threat, and information processing. It is no wonder that in monster films, most of our excitement and fear is generated by the audio mix. Hearing a threatening rustle behind us or the low bass frequency of heavy footsteps rouses our base survival instincts, which tell us to run from stalking or large predators. These sound effects are often more effective at evoking fear than a full-frame image of a monster.

Sound design balances a triad of sound categories: dialogue, sound effects, and music. Generally, the triad will be organized according to a hierarchy that privileges dialogue over music and sound effects. So when a character is speaking, this sound is brought to the foreground while all other sound is pushed to the background. We see this most obviously in very loud settings, like a nightclub scene, where we are still able to hear characters speak to one other. Similarly, when an important sound effect is featured, music or ambient noise is pushed to the background so that the sound effect can be heard crisply.

Each sound category provides the film with a different quality that might be featured or mixed with other qualities. Dialogue provides information, so it tends to be featured most prominently in the foreground of the sound design, which speak most directly and obviously to the audience. Some sound effects are treated this way too, handing over important information to the audience in an obvious way, like the sound of a failing engine that anticipates our hero’s car crash or the sound of a turning door knob that anticipates our hero’s partner returning home. These informational sound effects are made unnaturally loud so that they can dominate our sonic attention and speak to us directly. But most sound effects live in the background, creating a consistent and rich soundscape. The background sound design, usually constructed of music and sound effects, gives shape to the world and makes it feel consistent. Music and ambient noise bleeds between scenes to make them feel like they belong together. And though some music gives us an obvious sense of emotional peaks, most music and sound effects are unremarkable and work on our subconscious rather than our conscious viewing experience.

Silent Cinema to the “Talkies”

Given how important sound design has become in current cinema, it might seem impossible to find connection to its roots in silent cinema. But it is important to remember that silent cinema was never actually silent. Until 1927, when sound cinema became available to the general public, the movie theater was filled with live music accompaniment. The shift from silent cinema to “talkies” in 1927 was not from silence to sound, but rather it was from live sound to recorded sound.

In the U.S., silent cinema was shown with a live orchestra, band, or pianist seated in front of the screen. You can see such a setup in Sherlock, Jr. (Keaton, 1924), which features a movie theater with an orchestra dugout. The musicians would sometimes play a musical score that was written specifically for the film and would create consistency across all viewings in all cities. But sometimes the film did not come with a score, and this allowed for musical creativity. Specialized pianists would even improv music on the spot, without having seen the film in advance.

Other countries included additional elements into the sound mix of silent film. Japan, for example, had a tradition of using benshi (film narrators) who stood just to the side of the screen and worked with a musician to explain the film narrative and to play characters in dialogue. These benshi were not bound to a script, and so they had a lot of creative license in their performances. Many became celebrities in their own right, and audiences would buy tickets to specific film screenings to see their favorite benshi perform.

When sound technology was being developed in the U.S. in the mid-1920s, the aim was to standardize the film’s sound so that each viewing experience would be identical and to create a more cost-efficient industry. There were many up-front costs to changing the film industry to “talkies”. Studios would have to buy new equipment, develop new technologies, hire new voice actors, and build new sets. Theaters would have to invest in new projectors, sound systems, and sometimes even rebuild sections of the theater entirely.

Understandably, change was slow. Even though the first “talkie” The Jazz Singer emerged in 1927, there were many theaters that were not equipped to show the film. And for a transitional period between 1927 and 1930, many films were produced and released in two versions – a silent version that relied on live accompaniment and a “talkie” that required an updated sound theater – so that the film could play across the country in every theater. We see a similar trend happening now with 3D, IMAX, and VR versions of films where multiple versions of the product will cover multiple technological capabilities. A single film now can have a 70mm print for theaters with classic projectors, a digital print for most theaters, a 3D theatrical version, and can be distributed on DVD, Blu-ray, streaming platforms, and VR gaming consoles.

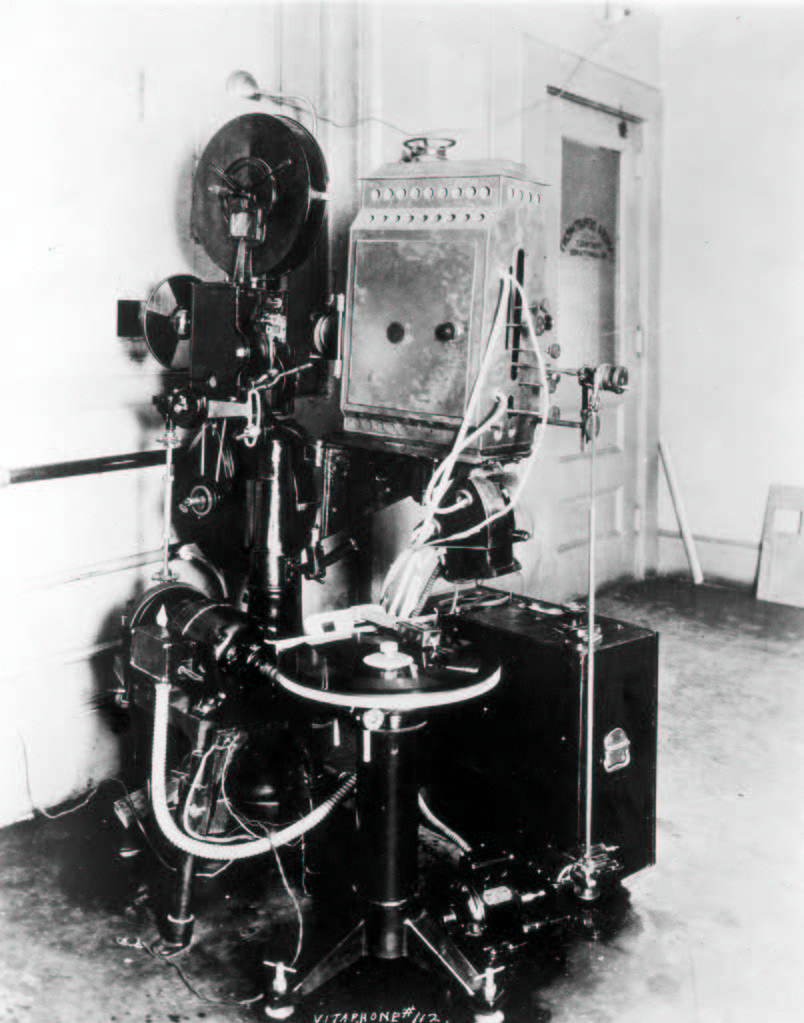

Similar to today’s digital climate, the sound technology revolution involved several companies who developed different technologies to meet the studio systems’ demand for synched sound. Vitaphone sound-on-disc, developed by Warner Brothers in 1926, paired a record player with a projector, thus pairing a sound system with an image system. Vitaphone technology debuted publicly with Don Juan (1926), where the New York Philharmonic Orchestra’s performance of the score was distributed on disc alongside the film image. But Vitaphone’s second feature, The Jazz Singer (1927), is largely known as the first “talkie” because it included dialogue on the disc as well as music.

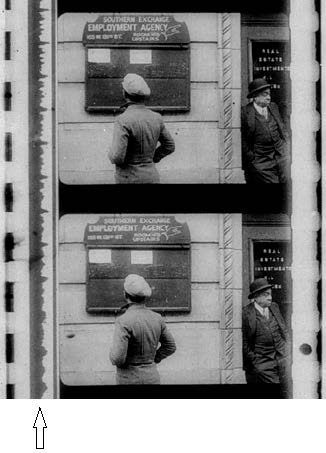

Another type of sound technology, sound-on-film or optical sound, had several competitors. The most influential system, RCA Photophone, debuted in 1927 with music and sound effects for the silent film Wings (1926). The sound-on-film or optical sound technology printed the audio track directly on the film strip itself, in a column near the sprockets. This became a far superior technology to the sound-on-disc, because sound was synched perfectly with image within the technology itself. Unlike sound-on-disc, which relied on a projectionist to start the disc and film at the same time and keep each element synched throughout the screening, optical sound needed only a specialized projector to be perfectly, mechanically synched. An optical soundtrack could also be cut just like the image portion of the film strip, so editing was more nuanced in sound-on-film than in sound-on-disc.

More technology needed to be developed to create a better-quality sound on set. Boom microphones were held over actors to capture dialogue more discreetly. Directional microphones captured sound from a single source, extracting it from the cacophony of noise around it. Cameras were first encased in blimps, huge moveable boxes with a window through which to film, so that the loud noise of cranking would not be picked up by the mics. Clapboards created synch points for image and sound (the visual of the clapboard closing with the sound of a “clap”). Many standardized visual elements of sets had to be changed because of the noise that they gave off – new lighting systems, set materials, and props had to be developed.

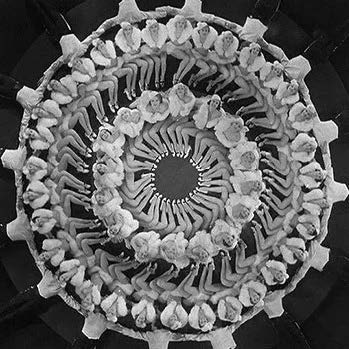

New genres were created to showcase all of this new technology. Starting in 1927 with The Jazz Singer, vaudeville performances were already the origin point for “talkies”. But as the industry advanced, radically new spectacles were developed to create the expensive and popular genre of musicals. MGM’s Busby Berkeley, a choreographer and director, dominated this genre with new advancements: moving cameras, crane shots, and geometric choreography. To see a Berkeley film, like 42nd Street (1932), was not at all like seeing a musical performance on stage, at a distance. Musical films brought the audience into the dance, above the dance, and below the dance. It was an immersive and playful use of emerging 1930s cinema technologies, bringing a light-heartedness to cinema that had been largely dominated by serious melodrama in the 1920s. Within the genre, several sub-genres emerged. “Singing sweethearts” featured duets between musical or dancer celebrities. “Aquamusicals” featured synchronized swimming and diving – cameras would film through large aquariums and above the water with cranes. “Backstage musicals” were self-reflexive, telling the story of a play or musical being produced.

Perhaps the most famous “backstage musical” is Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly/Donen, 1952), which tells the story of transitional filmmaking at the cusp of the “talkie” era. Set in 1927, Singin’ in the Rain showcases many of the production difficulties of the transitional era, like sound synchronization, microphone sound capture, and acting voices. But as a 1950s musical, the film also displays many contemporary conventions and technologies, like an upbeat tone, creative choreography, celebrity duets with Gene Kelly and Debbie Reynolds, and Technicolor.

Ironically, the advent of sound technology also allowed for film to become truly silent for the first time. Once audiences became accustomed to listening to sound – hearing it, differentiating its layers, interpreting it – the most radical way to get attention was to turn the sound off. In 1931, Fritz Lang’s M did just this. Contrasting boisterous musicals and chatty rom-coms, M turned to dark themes of child abduction and murder. When a little girl Elsie goes missing, Lang uses silence to show the gravity of her absence. We see shots of her empty chair at the dinner table, her ball rolling to nowhere, her balloon disappearing into the sky – all absolutely silent with no music or dialogue to ease the audience’s nerves or provide solace.

In M, Lang avoids a film score altogether. Especially in an early era of marveling at sound technology, this is a bold choice. Without music to guide our emotions, we pay more attention to the sound effects and diegetic music, like children singing about a man in black who’s coming to get them or like the killer’s whistle that indicates he is near. This whistle is cinema’s first use of leitmotif in film. By repeating the whistle when the killer’s shadow is on screen, the audience is trained to associate the killer with his whistle tune, and eventually its sound alone will start to conjure up the killer, even when he is off-screen. Between the dead silence and the leitmotif whistle, Lang showed that very careful and sparse sound design could carry audience tension, immersion, and emotion just as well as an overabundance of musical energy.

A lack of sound has always been uncomfortable to audiences, and current cinema has been using silence to create tension in thrillers and horror films. Uniquely, A Quiet Place (Krasinski, 2018) works silence into the diegesis by setting up a world where violent alien creatures attack by tracking noise. In this world, keeping silent becomes vital to survival. For the audience, a silent world is nerve-wracking to watch and physically immersive by creating lean-in moments to hear whispers and push-back moments at jump scares.

“Talkies”, even in the 21st century, have a continued interest in the traditions of silent cinema. Beyond using silent cinema’s creative visual techniques, some films adopt the interactive theatrical experience of silent cinema. Midnight screenings of Rocky Horror Picture Show, for example, will use actors in front of the screen who pantomime, parody, and interpret the film – serving a modern-day benshi function. Some films even take on the form of old silent film in order to evoke a particular time period. The Artist (2011) received accolades for its silent film form that told the story of Hollywood’s silent-to-talkie transitional period. The film used a recorded musical score, but the scarce dialogue was presented in intertitles, like a silent film. The Artist was only the second mostly-silent film to win a Best Picture Academy Award since the Oscars began in 1929.

Key Terms

Benshi: Film narrators who describe a silent film while standing just to the side of the screen. A Japanese tradition.

Talkie: Early term for sound cinema. The Jazz Singer (1927) is commonly descried as the first “talkie”, since it was the first sound film to feature spoken dialogue.

Sound-on-disc: Early sound technology that synched a record player’s sound with the projector’s image.

Sound-on-film (optical soundtrack): Sound technology that prints the sound track directly on the film strip itself. For celluloid film, this became the standard of production.

Boom microphone: A mic attached to a long pole. Allows dialogue to be recorded discreetly, without microphones embedded in costumes or props.

Directional microphone: A mic that captures sound from a single source. (As opposed to “omnidirectional mic”)

Blimp: A large box that encases a camera to dampen the sound of cranking.

Musical: New genre created in response to the rise of sound film. Features singing, dancing, and spectacle-driven camerawork.

Backstage musical: Musical subgenre that is self-reflexive, telling the story of the making of a musical.

Leitmotif: A musical phrase that comes to be associated with a particular character or place

Voice

One of the startling realizations of the sound cinema age was how important an actor’s voice quality is to their performance. During the transitional period, many actors lost their jobs because their voices were off-putting or wrong for the role. In some cases, dubbing became a way to add a quality voice to a famous face that had a poor voice. Voice actors can record song or dialogue after the film production itself, matching their voice tempo to the image. The result is a collage of talent: one facial performance meshed with a separate voice performance. In M (Lang, 1931), Peter Lorre, who played the child killer, didn’t know how to whistle, so Fritz Lang, the director, sang the whistle leitmotif for the film. Ironically in Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly/Donen, 1952), the actress Jean Hagen, who plays the brash-voiced Lina, actually had a lovely voice. In the film, when Kathy (Debbie Reynolds) appears to be dubbing over Lina’s voice, it is actually Hagen’s lovely voice that is being used. So in fact, the film is using ADR (Automatic Dialogue Replacement), where an actor will lip sync their own performance in an audio booth after filming for clearer audio quality. Recently, it has become more important to audiences that actors are singing their own parts in musicals. Films like the remake A Star is Born (Cooper, 2018) are marketed on the fact that their actors can sing and have done their own ADR work.

Good-quality sound that is well-synched to the image is essential for our immersion into a diegetic world. Without crisp sound and without synchronization, we consider the film to be of poor quality and find it hard to watch. Yet some famous, high-quality films contain moments of badly synched sound or badly recorded sound. For example, Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) has a moment of horrible dubbing early on when the character Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) says “you’ll get what’s coming to you” to her colleagues. The ADR recording is choppy, as though it was overly manipulated in post-production, and the sound doesn’t quite match Ripley’s mouth movements. But Alien is considered a classic, so just one moment of bad ADR does not necessarily ruin a film. Contemporary cinema, even amateur independents, are raising the bar of production quality, becoming more and more professionalized. This is due to emerging affordable softwares and technologies that allow anyone to create a recording booth at home and a sound design on their laptop.

But one area that still receives overwhelming critique is foreign film dubbing. Produced in one language, then distributed with dubbing from a new set of voice-actors, foreign language dubbing runs the high risk of un-synched voice and image and often the dubbed recordings are not merged well with the rest of the sound design. Many viewers prefer the work of reading subtitles in foreign films than listening to a badly-dubbed version in their native language. This inconvenience of foreign film dubbing and subtitling was created by the sound film industry. In silent film, intertitles were inserted between footage, so that audiences did not have to juggle both reading and viewing the film, and the intertitles were easily switched out with translations for global distribution. But the fast-paced nature of “talkie” dialogue required a more efficient way of conveying information to foreign viewers. Though subtitles are often an inconvenience, many viewers become accustomed to the process of reading-while-watching after the first act. We see evidence of this broad acceptance of subtitles in the first foreign-language Best Picture win in Oscars history, for the South Korean film Parasite (Bong, 2019).

Key Terms

Dubbing: One actor’s voice is replaced with another’s in post-production.

ADR (Automatic Dialogue Replacement): An actor records her own voice in post-production for crisper sound quality.

Subtitles: Captioned dialogue printed on the screen on top of the film image. Used to provide translated dialogue information in foreign-language films and captioned dialogue for hearing-impaired viewers.

Sound Effects

Similar to dubbing quality, sound effect quality is essential to the believability of a film’s diegetic world. We need the image to match the sound we hear in order to feel that the world is cohesive. This is achieved with sound fidelity (or synchronous sound), which ensures that each prop that we see on screen makes a believable sound in post-production. Foley artists work hard to find the right material to make the right sound. But this material is not always the prop that we see on screen. In order to get “good” sound, a radically different material might be used. For example, the sound of rain is chaotic and difficult to purely record. So Foley artists will often use the sound of frying bacon, which can be controlled in a studio, to simulate the sound of rain. Bacon has a crisp sound that is easily recordable and controllable, and when we hear it paired with the image of rain, our brains merge the two neatly. Other Foley pairings include crumpled chips bags to simulate fire, coconuts hit together to simulate horse hooves, and snapping celery to simulate bones breaking.

Although Foley switches out the prop’s sound for another’s, essentially “dubbing” one sound for another, it usually aims for sound fidelity because it aims to be invisible and continuous to the viewer. Alternatively, sound effects that are obviously different from the prop’s sound lack fidelity (they are asynchronous). These discontinuous effects are often used for exaggerated or comic effect. For example, a character’s horrible headache might be represented with the sound of a train whistle. The whistle is not the natural sound of a headache, but in this case asynchronous sound is the best way to exaggerate the agony of a headache. The train whistle is obviously unnatural and is not meant to fool the audience into a sense of realism. Similar asynchronous sound is used in the opening of Daisies (Chytilova, 1966), where two characters sit on the floor, moving their arms in robotic ways. Each robotic movement is paired with the sound of creaking wood, as though the characters are being described as wooden dolls and robots. The effect is comic, but it is also metaphorical, comparing the characters to inanimate playthings.

Once sound effects are created, their volume is determined by several factors. If the sound serves the general ambiance, like the sound of traffic in a city scene, the sound’s volume will be brought down to merge with the rest of the sound design background. But if this sound is subjective – for example, the sound of traffic is annoying a character who is trying to sleep – the volume might be brought up to showcase its importance. Sonic close-ups bring attention to a specific object or a specific experience. They are used to create subjectivity in a film and to bring the audience closer to a certain detail. In Blue (Kieslowski, 1993), sonic close-ups of ordinary objects, like a teacup overflowing with tea, bring us close to the grieving hero’s sensitive mental state.

It is not only props on screen that give us sound effects. A simple way of establishing off-screen action is with off-screen sound. This sound is still within the diegetic world, but it is just out of frame. Sometimes this out-of-reach quality can be intentionally frustrating; sometimes it is scary. But most often, off-screen sound creates the film’s atmosphere and is essential to our subconscious acceptance of the story world’s believability. An envelope of sound makes our central characters, who are often on screen, feel like they are part of a larger world, which is often off screen.

Just as camera framing and movement choices create visual subjectivity in film, sound perspective creates aural subjectivity, carrying the viewer on an intimate journey of the story world. Sound perspective will often match a visual close-up with a sonic close-up. The more intimate we are with an object, the better we can hear it. And the more intimate we are with a character, the better we can hear what they hear. In Beasts of the Southern Wild (Zeitlin, 2012), we can hear our hero’s thoughts in voice-over narration along with the sounds that she experiences directly. When the hero picks up a chicken to listen to its chest, we hear the chicken’s heartbeat loud in our ears too. This sound perspective brings us emotionally closer to the hero, who becomes our prosthetic eyes and ears in the film world.

Perhaps the most famous use of sound perspective is in the opening of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, where a 3-minute long-take crane shot takes us over a city to track a car carrying a bomb in its trunk. At the start of the long take, we see a bomb placed in the car’s trunk, then when the car is turned on, its radio blasts loudly. As the car weaves through the city and the camera alternately loses it and catches up to it, we can hear that radio music constantly. Through Welles’s use of sound perspective, we can judge how far away the car is from us (and the camera) based on the radio music’s volume. When the music is faint, we instinctively know that we are losing the car. Even when off-screen, the car’s presence and movements are felt through sound effects. When the car swings back on screen, the radio music volume blasts up, almost congratulating us for finding it. In Touch of Evil, Welles teaches filmmakers how to effectively create tension and immersion simply through the careful staging of sound.

Key Terms

Sound fidelity (synchronous sound): Each prop that we see on screen makes a believable sound in post-production. The image and sound appear to match.

Lack of fidelity (asynchronous sound): Sound effects are obviously different from the prop’s “natural” sound. Often used for exaggerated or comic effect.

Foley: The reproduction of everyday sounds using various materials in a studio. Named after the sound-effects artist Jack Foley.

Sonic close-up: The volume of a certain sound effect is increased to bring attention to an object or experience.

Off-screen sound: Diegetic sound whose action is out of frame.

Sound perspective: Matches camera distance to sound volume. Sonic close-ups are matched with visual close-ups. Sound becomes muffled when it is far away from the camera or unimportant to the story.

Music

Film music takes the audience on an emotional journey that is largely based on instinctive reactions to certain sounds. Music scored in major keys will evoke joy and power in a film scene. Music scored in minor keys will evoke sadness, tragedy, or fear in the film scene. Hitchcock once described music as “company”, and this is a great way to explain the musical term “accompaniment”. In film, music serves as company for the characters and the audience, and so it can provide us with relief in the most intimately painful experiences. Our own feelings of loneliness are never as poetic or entertaining as a tragic hero’s alienation when paired with a delicate, mournful soundtrack.

For some directors, this concept of musical “company” influences their decision to not include a score in their film. For example, Hitchcock decided not to hire a composer for his film Lifeboat (1944), which takes place entirely on a lifeboat floating in the middle of an ocean. When questioned on this decision, Hitchcock would retort: In the middle of an ocean, where would the orchestra sit? The film creates a high sense of isolation simply from the lack of aural “company” for the characters and the audience. Taking a cue from this technique, Zemeckis didn’t want a musical score for his film Cast Away (2000), also a film about being stranded at sea. But Zemeckis did hire the composer Alan Silvestri, though he asked him to compose “music” without the use of instruments. Silvestri thought about this challenge carefully, and he started to record the sounds of wind in place of traditional instruments: happy wind tunes, tragic wind tunes, fearful wind tunes. The resulting orchestration of sound effects does not serve as non-diegetic “company” to the story; rather, it is completely naturalized in the story world and gives hints as to an emotional journey without feeling obvious and overly-manipulative to the audience.

Many directors will work with a single composer for their entire careers, creating a tonal consistency across their films. Hitchcock worked closely with Bernard Herrmann for many of his films, and Herrmann was instrumental in creating the mysterious, disconcerting tone of thrillers. For Vertigo (1958), Herrmann used two undulating musical phrases that meet to alternately create harmony and dissonance. This score is a musical representation of the feeling of vertigo, alternately falling and picking itself up. It also keeps the viewer on edge, unsure of how the narrative will progress. Christopher Nolan works consistently with Hans Zimmer to create the tense scores for his films. Zimmer is known for his overblown brass notes and has been credited with starting the trend for “braaam” sound effect in action movies and film trailers. In Inception, Zimmer’s style of incorporating traditional orchestration with electronic distortions matches the film’s themes of artificially created, yet naturalized dream-worlds. Through both Herrmann’s and Zimmer’s scores, the orchestration matches the film themes to enhance them.

Other soundtracks are filled with pop music to achieve similar effect. The first film to use an entire score recorded by a pop musician was The Graduate (Nichols, 1967), and it revolutionized the landscape of film soundtracks. For The Graduate, Nichols hired the popular band Simon & Garfunkel to use some of their pre-written tracks and to write some new ones. The most famous track of the film album, “Mrs. Robinson”, was actually a pre-written track titled “Mrs. Roosevelt”, whose lyrics were slightly changed to match the name of the film character. The songs on the soundtrack, like many Simon & Garfunkel tracks about counterculture movements, are mournful and pessimistic, even when upbeat. The track “The Sound of Silence”, which repeats three times in the film, perfectly matches the film’s themes of loneliness, lack of ambition, and life stasis.

Since The Graduate, many films have taken the approach of hiring a single artist or band to create the entire soundtrack: from Cat Stevens’s Harold and Maude (1971) soundtrack to Radiohead’s Suspiria (2018) soundtrack. Others have heavily featured a single artist in the soundtrack, like Kendrick Lamar on the Black Panther (2018) soundtrack. But most films now feature a medley of artists who each contribute a different tone, emotion, or association to the scene. For example, The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) uses Paul Simon’s “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard”, an upbeat song about juvenile delinquency, to match a montage where a grandfather teaches his young grandkids how to steal and gamble. The film also uses Elliott Smith’s “Needle in the Hay” to enhance the sadness and desperation of a character’s suicide attempt. And it invokes 1970s nostalgia and associations with gentle, pleasing ballads through Nico’s “These Days” track.

Sound Design

Soundtracks create a “wallpaper” for films that can cover over imperfections in other areas, such as mise-en-scène continuity, script quality, and acting. The job of a Sound Designer is to create a cohesive world that feels alive with energy, momentum, and possibility. Unmotivated lags in the soundtrack or moments of “bad” sound can ruin this sense of a cohesive world, and thus break this “wallpaper” continuity.

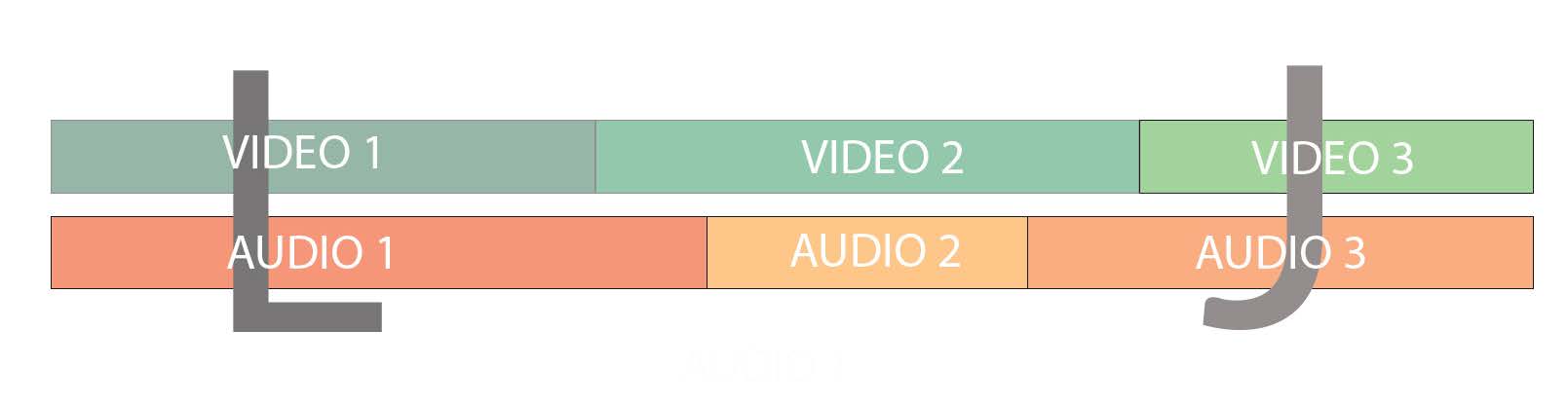

Along with dubbing, Foley, and musical soundtracks, Sound Designers use a few standard principles to create realistic and believable soundscapes. One standard practice is sound bridges, which take sound from one scene and bleed it into another. This creates a sense of continuity between sharp cuts and keeps the viewer involved in the story without being put off by the sudden change in scenery. A sound bridge can join scenes in two ways: it can bleed sound from the next scene in the first (a “J cut”) or it can bleed sound from one scene into the next (an “L cut”). J-cuts anticipate the image that will come. L-cuts remind of the image that was just seen.

In The Graduate, J-cuts are used to merge two different lives that the main character Benjamin is leading: life at home after college and an affair with a married neighbor. In a sequence that is meant to show how Benjamin confuses his two lives, we hear his father’s voice bleed into an intimate bedroom scene. We see Benjamin in his lover’s bed while hearing his father accuse: “Ben, what are you doing?” As Benjamin turns his head to look up, the film cuts to a shot of his father outside, looking down on him. At first, it appears as though Benjamin was caught in a compromising position because of the J-cut that bled his father’s voice in from the next scene. But in fact, we realize, Benjamin is just floating in the pool outside with his father accusing him of being unambitious and lazy.

In The Graduate example, the J-cut is used for discontinuous effect, to confuse and worry the viewer. But most J-cuts simply set up the sensory envelope for the next image. Before we see an establishing shot of the glorious Jurassic Park island, we want to be set up with a bit of glorious music and the sound of helicopter propellers in the previous shot. Or before we see the face of our hero’s long-lost love, we want to hear her voice say “Hello, stranger” while the camera is still on his face.

L-cuts work in the opposite way – they linger on what we had just seen as we move into the next image. If we want an emotion to follow into the next setting or time-period, we might use an L-cut to bleed a previous piece of music or sound effect into the next establishing shot. For example, in the opening of Apocalypse Now (Coppola, 1979), the audio memory of the Vietnam War bleeds into our hero’s present time: as he stares at a ceiling fan, we can still hear the sound of helicopter propellers. Or an L-cut might hide the visual cut in shot/reverse-shot editing: one character might be ranting angrily, and while we are still listening to his words, we visually cut to his partner’s face looking aggravated at the lecture.

Another key tool to use in hiding the artificiality of soundscapes and editing cuts is room tone. Every room, unless extremely well-padded, emits a unique room tone that will be recorded in every actor’s microphone. Cutting between recorded on-set sound and ADR feels artificial and choppy unless the room tone is layered over to “wallpaper” the two audio clips together. Often, room tone will be recorded separately to serve as this bridge between variously recorded clips, and often it is not noticeable to the audience. But some filmmakers, like David Lynch, will intentionally bring attention to the room tone, creating an intentionally discontinuous effect. See, for example, Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) to hear how high-volume room tone will sound like a terrifying factory soundscape of gears turning and textures shrieking.

Like asynchronous sound effects, Lynch’s soundscapes often feel unnatural and unfitting to their image. For example, in the opening of Blue Velvet (1986), the camera fluidly lowers from a suburban yard down through the grass and into the earth, which is crawling with bugs. As the camera lowers down, the soundscape moves from the 1950s track “Blue Velvet” to a medley of Foley effects that include squishy mud sounds and mechanical drum spinning. The Foley soundscape is not meant to be synchronous with the image of bugs, but it is meant to obviously evoke a sense of disgust that represents the underworld living just under the surface of a 1950s-style suburbia.

Ultimately, sound design is meant to guide our interpretation of the image. Objective soundscapes tend to create a synchronous, stable stage upon which experiences can unfold in a realistic way. Subjective sound, often inserted into this objective soundscape, will give the audience peaks of individual experience, sometimes asynchronous and usually immersive. These peaks of subjective sound bring emotion and personal experience to the image through various forms of sound perspective. In this way, we see that “good” sound design corresponds to the goals of “good” image: both create a believable and naturalistic world and also provide particular worldviews or points of view of that established space.

Key Terms

Sound bridge: Bleeds sound from one scene into another. Creates a sense of continuity between sharp cuts.

J-cut: A type of sound bridge that bleeds the next scene’s sound into the first scene’s image.

L-cut: A type of sound bridge that bleeds a scene’s sound into the next scene’s image.

Room tone: An ambient sound that is emitted from every room. Recorded room tone provides naturalism to a scene and helps to blend together sound recorded from different sites (for example, on set and in studio).

Listen Closely

This chapter is adapted from FILM APPRECIATION by Dr. Yelizaveta Moss and Dr. Candice Wilson.