7 Science Fiction

Science Fiction

George Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1902) is widely considered one of the earliest examples of the science fiction film that set key conventions of the genre – spectacular use of special effects, journey to another world (the moon), and the iconography of aliens and space ships producing themes of space travel, discovery, and the fear of the unknown. The science fiction plots tend towards themes of science, technology, ethical or moral anxieties, and philosophies that shed light on humanity and society. Visual effects and advanced technology props, such as teleportation machines and hovercrafts, characterize science fiction as a speculative film genre imagining future technologies and realities. Characters range from aliens and artificial intelligence to scientists and government officials. Sci-fi heroes often bear the sacrificial weight of trying to save the world.

The prototypical story of the sci-fi genre revolves around the device of the novum, Latin for the “new thing”. The novum is a technology or cultural trend pushed into a logical, but often dystopian, endpoint in order to distance it from the audience, making it appear foreign. The punch line of these films is often that the novum is not actually a “new thing” at all. The plot reveals that the future version of the “new thing” was on earth all along or was Earth itself. For example, Planet of the Apes (1968) tells the story of American astronauts who crash onto an unfamiliar planet in the future where intelligent, articulate apes subjugate mute humans. The film ends with the shocking discovery of a buried Statue of Liberty by the lead astronaut (Charlton Heston) as he escapes his enslavement by the apes, and the horrible understanding that this strange future planet, the new thing, is actually Earth.

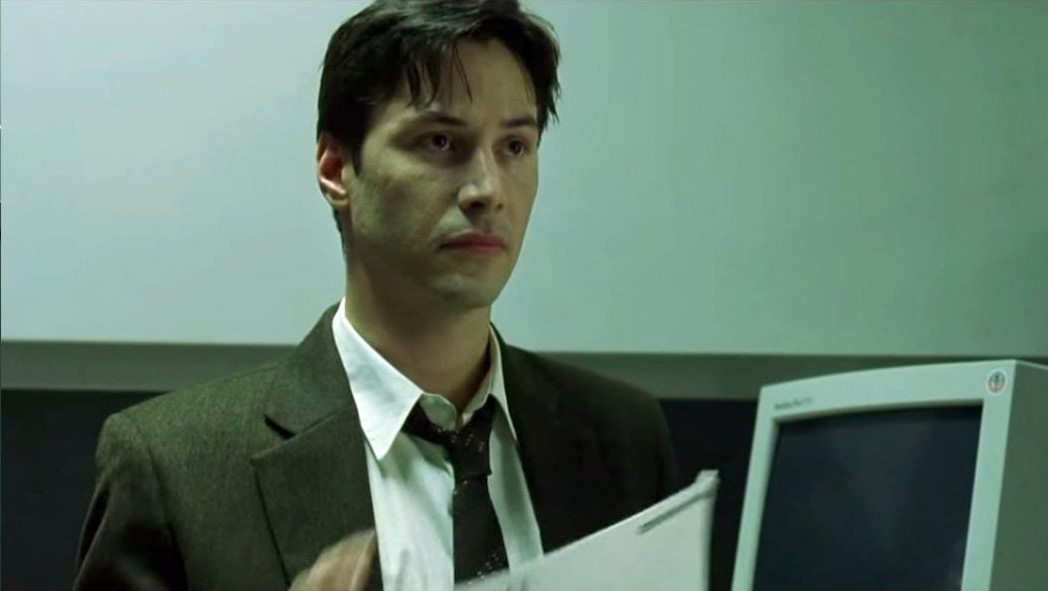

The Matrix is also set in the future, but one where machines have taken over the world, manufacturing incubated humans as batteries and keeping these humans subdued and unaware in a virtual world (the Matrix). The real world, on the other hand, is a dystopic space where the last remnants of freed humans fight a losing battle against the machines in a long drawn out war. Computer programmer Neo (Keanu Reeves) discovers the deception and becomes ‘The One”, a special person able to move freely through the different realities of the Matrix and the real world, and a hero destined to save humanity from their enslavement. The Matrix uses the figure of an everyday worker, a spiritually empty cog in the machine, to reflect a general malaise of contemporary audiences towards a capitalist society. And the film reinvigorates a need for ‘reality’ in the audience through Neo’s virtual body and his experiences in the Matrix. In Neo, we are given a young man desperate to believe that he is special, distinct from all the other copies and illusions as he fights to defeat bureaucratic clones within a hyper-industrialized landscape.

Genre is not static; rather, it is heavily influenced by its current cultural environment. In this way, genre films are time capsules that contain the specific cultural references and mindsets of the time and place in which they were made. Science fiction film would experience a surge in production in the 1950s, a period also known as the Golden Age of Science Fiction Films, due to the famous UFO sightings in the late 1940s into the 1950s near Roswell, New Mexico, and in Washington State. And during this Golden Age, the films’ theme of anxiety about mass destruction is clearly influenced by common 1950s nuclear and communist fears. With images of the massive destruction of the atomic bomb in Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945, Americans were more aware than ever before of the ability of man to destroy himself and others. The rise of Communism and the continued threat of nuclear warfare during the Cold War in the 1950s led to widespread paranoia concerning the infiltration of communists within American lives. This ‘Red Scare’ resulted in witch-hunts, loss of employment, and imprisonment, touching all areas of American society. Numerous sci-fi films such as The Thing from another World (1951) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) tapped into a pervasive fear of communism imagined through themes of infection, the uncertainty of identity, and the notion that the enemy looks just like you. The subgenre of the monster or mutant film would also emerge from these apocalyptic concerns, and lend itself to a reworking of the horror genre.

In blending genres, Ishiro Honda’s science fiction kaiju (monster movie) Gojira (Godzilla) (Honda, 1954) remains one of the most successful monster-as-allegory films. Gojira emerged both from the trauma of the atomic bomb and the awareness of nuclear warfare as a continuing threat to Japanese lives as evidenced by the Lucky Dragon 5 incident, in which radiation exposure continued well after combat. Six years after the end of World War II, American military tested a hydrogen bomb near a Japanese fishing vessel filled with civilians, exposing them to radiation. As a reference to the Lucky Dragon 5 incident, Gojira begins with an explosion of light that destroys the peaceful routine of men on a fishing vessel. This light configures the monster Gojira as an allegory for an atomic bomb. Later in the film, characters watch the aftermath of Gojira’s rampage through Tokyo on television. The panning camera shows a Tokyo in ruins, deliberately recalling the war torn post-World War II landscape. Honda used singing children to create sentimentality and, in highlighting the true victims of nuclear threat, stressed the importance of peace. The figure of a scientist in a lab coat is a crucial character within the sci-fi film universe because he translates a scientific or rational decision into human terms. It is through his humanity, or lack thereof, that we understand the stakes of the crisis and political response. In the end of Gojira, after using a powerful weapon of mass destruction to destroy the monster, scientist Serizawa sacrifices his own life to take the secret of his weapon to his grave in fear that the inherent weakness of man will lead to his weapon’s use for further global warfare.

Traditionally, science fiction as a genre privileges male leads and, thus, largely male action and concerns. In earlier classical film, women chiefly occupy the role of damsel in distress, object of desire, or subordinate sidekicks who serve little purpose beyond propping up the male lead. Even as late as Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope (1977), arguably the most culturally impactful science fiction film in contemporary cinema, the male robotic drones had more dialogue than the ‘real’ women did in the film. The Second Wave of Feminism in the 1960s-1970s ushered in new representations of women with the agency to act and make decisions on their own in Science Fiction cinema. Ellen Ripley in Alien (1979) provides the quintessential example of a strong female lead at the helm of a historically male-oriented genre. The huge success of the Alien franchise would lead to increased visibility and popularity of female heroes within the sci-fi landscape who escape gender expectations placed upon them. In more contemporary films, like Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991), Arrival (2016), Gravity (2013), and Her (2013), female perspectives and storylines have occupied a greater stage. This evolution of the sci-fi genre shows how the film industry has evolved according to audience expectations and has negotiated the complexity of gender politics in the world today.

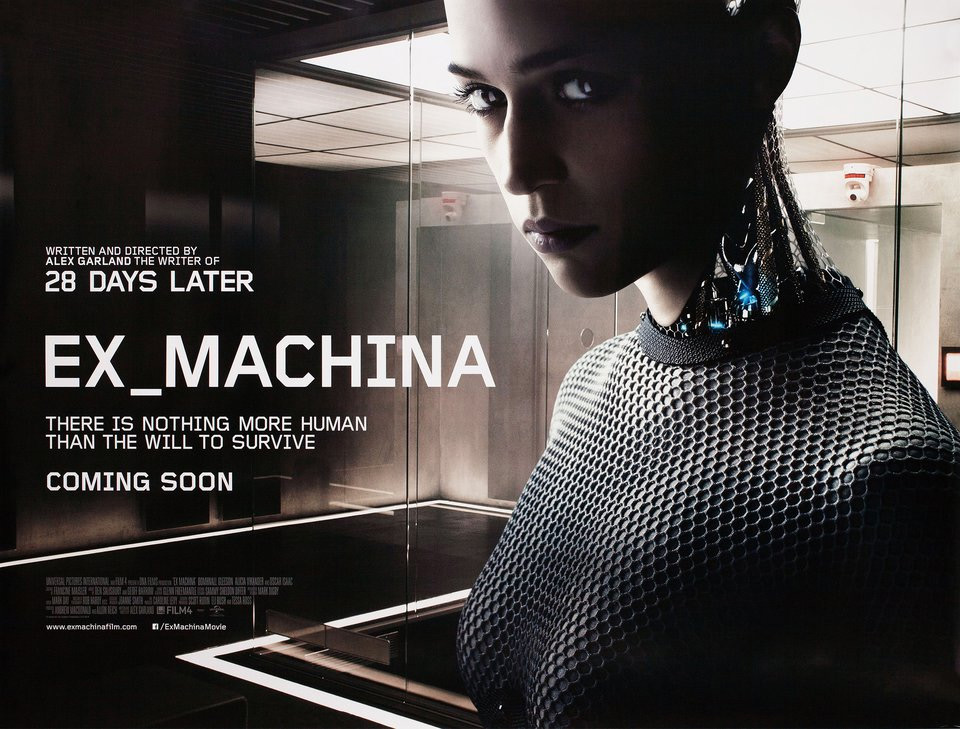

In the Ex_Machina (2014) poster, the shocking image of a young woman’s interior circuitry clues us in to the thematic tension between human and android that will be central to the film. While the sterility and futuristic feel of the lab setting suggests that the genre belongs to science fiction, the text of the poster warns of the machine’s human desire “to survive” and the low-key lighting of the shot indicates the possible presence of another genre – horror. By highlighting the internal “difference” of the female android from a female human, the poster troubles the common sci-fi message that humanity is essential to “save the world” and poses a monstrosity in the android’s enigmatic quality that is so close to being human. The film refuses to hide the android qualities of this almost-human character, and her obvious android-ness forces the audience to meditate on contemporary fears of scientific excess and gender relations. Ada, as an android, shatters the binaries of gender expectations and refuses narrative confinement within romantic plotlines with her male leads. She defies the trope of the damsel in distress while also manipulating the same trope to escape her enslavement by performing fear and helplessness for the male characters. Androids and cyborgs in sci-fi cinema build upon the themes of what is widely considered the first science fiction text, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), which is about the artificial creation of life and the scientist who is horrified at his creation. In Frankenstein , we explore the idea of playing God and questions of the human, and we also grapple with our own humanity in the face of scientific progress, race, gender and other social concerns.

Key Terms