Bit-thakkar izzaman elli gubl lughatil ensan

Lamma-ellugha-elwahidi kanat juz’eyyat

Ughniyat alkhabour wal furat…

I remember the time before the language of men. When the only language was elemental: the sound of fish jumping out of the river, the temperature of the wind on skin, the coarseness of the soil under feet. The Land had a personality and I spoke to whomever would listen. And if you were interested in survival, you listened…

Are you listening?

(Land ‘blows’ pieces of map to Daughter. Daughter chokes.)

Debórah Eliezer’s voice is so material I feel like I could hold it in my hand like a fruit. Her prolific voiceover work is tangible when she speaks. She is quick-talking, hand-talking, and given to casual swearing in a way that puts me at ease. We’re meeting for breakfast the morning after the playwright/performer’s solo show (dis)Place[d] at the 2019 Ko Festival of Performance in Amherst, MA.

(dis)Place[d] is a deeply personal story about Iraqi Jews, whose history in Iraq stretches back thousands of years and who now live almost entirely in diaspora. Told by a daughter of that diaspora, the play stages Baghdad by drawing on fragments of stories and what’s unearthed as her body strains to remember sensations, words, and melodies she didn’t know she knew. It constructs a landscape not from a traditional map but from what’s left after a generation of displacement, assimilation, migration, and participation in settler projects—actions made variously by choice and chance and violence. Together, consciously or not, all surviving Iraqi Jews create this relational landscape that exists only because of the clash of identities produced when a community has to scatter. Maybe this is why Eliezer’s Iraqi cousin (as Eliezer tells me, recounting their recent meeting in her cousin’s home) so eagerly exclaims Talk to me about your show! “She wants it, like she wants to drink it,” Eliezer says. “Because that’s her. But she has not been able to acknowledge that.” Eliezer describes a palpable yearning among Arab Jews today to connect with where their families came from. Stories of Jewish Baghdad are sparse. As in all such cases, the stories that do exist get burdened with the task of representing the entirety of Iraqi Jewish experience. The task’s an impossible one.

From a menu that deploys the word local alongside farm-fresh and organic, like a combined uber-brand, I order an omelet with peaches (a fruit Spanish explorers brought to the Americas in the 1500s) and brie (a soft cheese named after the region of France to which it’s native). One of the key ways Eliezer traces her connection to 1930s Baghdad in the play is through food.[1] Here, in this New England college town, local seems to be shorthand for meal-length absolution from the generic sin of global citizenship and industrial food distribution. It doesn’t have anything to do with where we are.

Eliezer wonders: what would it mean for her cousin, living in a former Palestinian village that’s now peopled by the Iraqi Jewish diaspora, “to sit there and to say, this is our state, and our land, and where we have this country; and then to say, And I came from this other place. And I, too, am an Arab. What will that do to the peace process? To say, I am of you?”

Eating my omelet, I consider the link between fetishizing the local and yearning for connection to place. Both foster the impulse to defend here from not-here. The seeds of violence. Borders. I wonder about whether and how performance can disrupt that link. Performance is uniquely local and uniquely mobile. It’s live, so it’s happening where it’s happening and only there, with those people, in that room. But it can be packed up and taken elsewhere, to happen only in that elsewhere, with those other people, in another room: an entire world is witnessed into life, partially on the stage and partially in each audience member’s mind, but the transferability of that world troubles geographic borders. A place can be a poetic construction, a collaborative waking dream.

But such poetry can in fact translate to new borders. “Even my Arab-Jewish relatives talk about Arabs as ‘the other.’ So what are you even saying with that? What does it mean to be of a place?” Eliezer asked the audience the night before during the post-show discussion. “You’re living in an Arab land!…When you say ‘We’re Jewish,’ what are you saying? We’re not Muslim?” Her questions, though rhetorical, evoke the State of Israel—a state that literalized Jewish longing for a homeland—as one example of the violent exclusion that intertwined claims to identity and claims to land can produce. Will a poetics of landscape[2] always be vulnerable to instrumentalization by those who want to wall off land for their own?

***

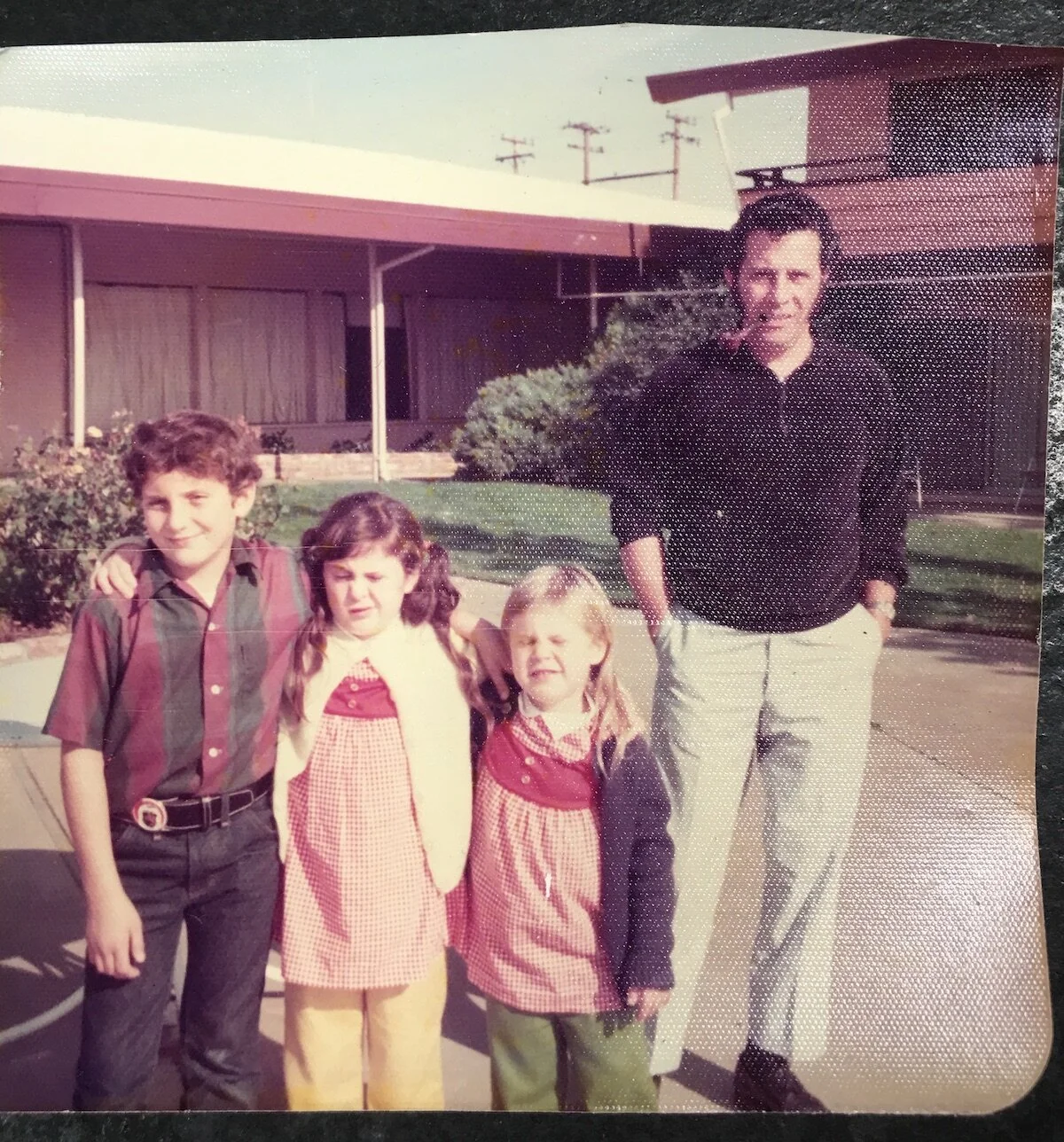

Roaming an unfamiliar internal landscape in (dis)Place[d], Eliezer feels, through her body, for answers to the question What does it mean to be of a place? The play’s central characters are Aba; the Daughter; and the Land (all three played by Eliezer). In one of the play’s layers of time, we’re in present-day California, where the Daughter visits her father, her Aba, who’s lost his memory.[3] He’s still himself, though, charming as ever, preening when the Daughter tells him his new haircut makes him look sexy. Aba speaks in gibberish, which the Daughter describes as a choice.[4] But the Daughter is missing her memory too. Aba has moved through the world since before the Daughter’s birth as an assimilated American Jew from Israel. “Something’s missing,” the Daughter repeats throughout the play. Something doesn’t add up. Why does Aba sing a melody that stands out, in their California synagogue, as different? Why didn’t he teach her? What is this piece of map he’s swallowed?[5]

In another layer of time, we are with Edward: Aba as a boy, growing up in Baghdad in the 1930s and 1940s. He’s one of 80,000 Iraqi Jews in the city at the time (and 130,000 across the country).His story is patchy, like a blacked-out transcript,[6] full of jumps and caesuras.

[7] Thanks to the protection of a Muslim neighbor and friend, Edward and his family live through the farhud in 1941, a pogrom in Baghdad that kills close to 200 Jews. The family stays, as indeed most do; a mass permanent departure of Jews from Iraq won’t occur until the early 1950s.[8]

Beloved Iraqi Jewish singer Salima Murad (1905–1974), nicknamed “Pasha” by the Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said, who stayed in Iraq until the end of her life.

In the meantime, Baghdadi Jews rebuild fast: new schools, new homes, new hospitals. They’re politically engaged—some become Zionists, “but many more [wave] the red flag.” Many who left immediately return following the farhud.

Still a child, Edward joins the Zionist underground.[9] Years later, as a teenager, he leaves Iraq to join the kibbutz movement. It’s a passionate choice for him, but a desire to go to Palestine is far from the prevailing sentiment among Iraqi Jews.[10] Once Edward leaves Baghdad, he is gone for good. And this is where his origin story, for the purposes of the play, breaks off. It ends where Aba believes he begins, at his transformation from Edward to Uri. The Edward we see is a person he tried to bury in time.[11]

(dis)Place[d] is part documentary and part auto-ethnography; the nameless Daughter is Eliezer. Most of Aba’s words in the show, and his stories, come from a film of her father that Eliezer put off watching for eight years. She knew that if she watched it, she says, she’d have questions, and if she had questions she’d need to make a show, and making a show would be hard. Once you open up a memory, you’re making yourself vulnerable to everything that might have happened to it in storage: bits gone missing, deterioration, rot.

Time lapse on top of time lapse. Chasing memory and fearing it, at once. The source of the story’s blackouts are multiple: Aba’s self-exile into intentional forgetting, Eliezer’s indirect and delayed access to his memories after his death, and the distance between Iraqi Jews of Eliezer’s generation and Iraq as place, as land.