Two women, one imprisoned for her words and the other for her armed resistance. One a poet painting her reality behind bars, the other picking up poetry to keep her sanity. One was always engaged in her craft and the other self-identified as a bad poet, more interested in escaping confinement than honing a craft.

Dareen Tatour was arrested by Israeli police on October 11, 2015 for her poem “Resist My People, Resist Them” and for two Facebook posts. Souha Bechara was arrested in 1988, at the age of 21, for the attempted assassination of the head of the South Lebanese Army, a mercenary militia funded by Israel to maintain the occupation of south Lebanon.

Dareen Tatour spent three years in a combination of prison and house arrest before being released. Souha Bechara spent ten years in solitary confinement in the notorious Khiam prison and was released in 1998 after an intense Lebanese and European campaign.

Following are two poems: The first—by Dareen Tatour, written from Israeli prison in 2016. The second—written by Zein El-Amine some years before that, after a day spent interviewing Souha Bechara at her home in Beirut.

Zein El-Amine was born and raised in Lebanon. His poems have been published by Wild River Review, Foreign Policy in Focus, Beltway Quarterly, DC Poets Against the War Anthology, Penumbra, GYST, Joybringer, Folio, Ghostfishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology, and Citylit. His short stories have appeared in Uno Mas, Jadaliyya, Middle East Report, Bound Off, and more.

A Poet Behind Bars(By Dareen Tatour; Translation by Zein El-Amine)In prison I met people, |

شاعرة من وراء القضبانبقلم: دارين طاطور

|

How to Write a Poem, According to Souha Bechara

(Zein El-Amine)

Sit in their circle.

Don’t let your eyes linger

on any object in the room.

Extract yourself

from your body. Watch

the man with the hairy hands

describe the rape of your body

to the body. Watch him

as he begins to beat the body.

Focus on the arc

of your liberated lower molar

and make it everything:

try to guess where

it landed, crawl to it,

find it, save it for later.

Think about putting it back

in one day. Ignore

the wheeling of the cart.

Ignore the stripped cable

dangling above you.

Find the tooth.

Make solitary confinement

your longed-for-solitude.

Climb the walls:

Press your palms on one

wall, fingers pointed

to the ceiling. Press

your feet against the other

wall. Build pressure,

step up with one foot

and up with one hand.

Repeat until your back

touches the ceiling. Now

survey the room. Do this

once at mid-morning

and once at mid-afternoon.

Repeat daily. Do this

for a decade.

Make that crack

under your door

your world: lie down

and face the door; look

past the roaches,

fleas and lice

into the compressed light;

wait for it to be

interrupted. Study the soles

of your captors.

Match the voices

with the soles,

match the soles

with the names.

Catalog them:

the pigeon-toed,

the limping soles,

the canvas ones,

the wooden ones.

Delight at new soles.

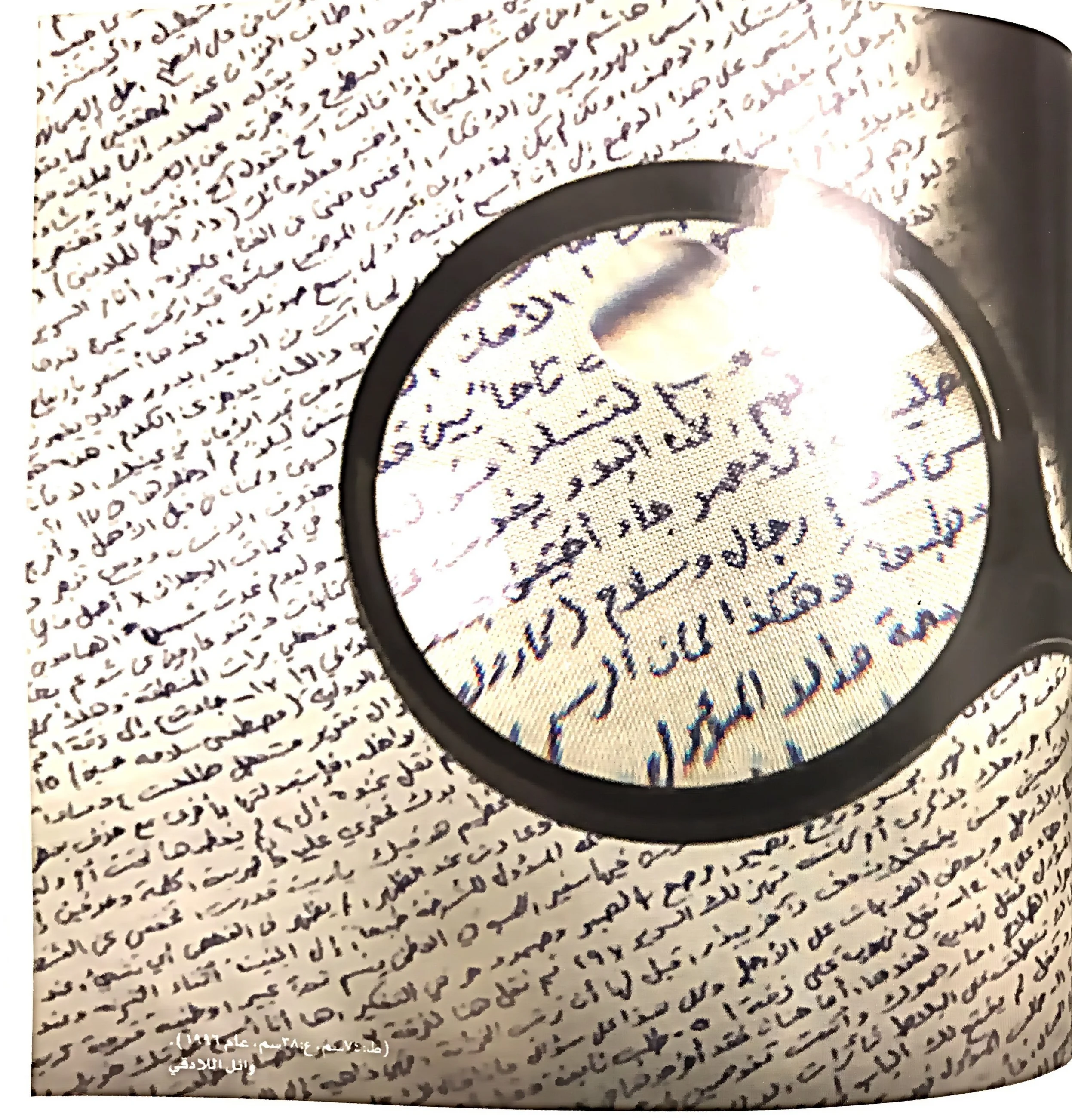

Find a piece of graphite.

Separate your toilet paper

into plies. Stretch

your scroll on the floor.

Prostrate yourself.

Grab the graphite

between thumb

and forefinger.

It will feel crippling

at first, your words

will be undecipherable,

but you will

eventually write

your tiny words

with smooth curves.

Set your intentions.

Don’t think of meanings,

think of the time

it will take to write

your microscopic epic.

After all, this is about time

not about metaphors

or similes or such.

It’s about rhyme

and meter.

So limit hope to the word,

then extend it to the line,

then to the stanza,

then reach out for the

winding night.

Now write your first faint line.