Rooted in the Future

Mirna Bamieh

“Food has always been a representation of class, time, and power. It creates a unique atmosphere conducive to encounter. Sharing food sets the table with aspects of hospitality, distribution, exchange, familiarity, and pleasure. A shared meal can become a space for reflection on socio-political realities, attitudes, fashions of the time, and even the suppressed elements of history.”

Below, Bamieh charts her journey of creating Palestine Hosting Society as an ongoing project that lives in this reflective space.

My artist bio described my looking at liminal spaces that have been residing in their liminality for so long that liminality and in-betweenness are the only reality that exists. The last video piece I produced in 2015 was entitled “A tutorial on how to disappear, become an image.” In it, I closed my eyes for the last time on a screen. I realized that I missed people, I missed their voices in my life—and my life is really my practice, my art practice. I could tell you the story of how this missing happened, and I could describe for you the scene in which my whole practice as an artist collapsed in my heart. I could tell you how in one night I decided that if the world were to fall apart, and I was one of the survivors in a post-apocalyptic future, I would like to be a cook. That exact moment of realization, in the summer of 2016 during an art residency in Tokyo, began the snowball of culinary and life decisions for my art practice and beyond.

Three years ago, I would never have thought that I would create a project called Palestine Hosting Society. But I did. It changed my life, but in 5 years my life will be different again and I might create something totally different. We come from a place where politics—and the future—are very hard to predict. Things keep changing but at the same time are very static. We cannot even imagine a time with no Israeli state.

Three years ago, I would never have thought that I would create a project called Palestine Hosting Society. But I did. It changed my life, but in 5 years my life will be different again and I might create something totally different. We come from a place where politics—and the future—are very hard to predict. Things keep changing but at the same time are very static. We cannot even imagine a time with no Israeli state.

That’s the struggle: our existence is based on resisting the efforts to erase us.

There is a layer of dreaming throughout all of this. That is why I believe that Palestinians have a very rich imagination: we imagine our identity all the time, in order to exist. We keep reinventing ourselves.

We were never on the privileged side, we never had ready answers, we never had a plan.

For Palestinians the question of nostalgia has always been very tricky, because there are negative connotations to it. Some think that because we are very sentimental and nostalgic, we will never keep up with the world. We’ve been having the same struggle for 70 years now and we miss something that does not exist anymore. The homeland does not exist in the way that we imagine it. For my generation it is important to bring back this space of belonging, knowledge, the relation with the land, the know-how, the seasonal practices, the things we forgot over time. Focused on intifadas and survival struggles, the generation before us had limited space to tend to these things. But their struggle cleared the way for my generation to begin, from a place where we can bring our relation to the land into the present and produce something of great value for ourselves in the future. Things will never be the same, we might not wear the embroidered dresses like our grandmas used to, but if we have the knowledge of what it meant for them, we will respect it more.

With the damage we have caused to earth and the escalation in how nature is manifesting its harsher face, there are survival tools and sensibilities in ancient wisdom that might save us in a future of scarcity, vulnerability, and uncertainty.

مبروشة مع مربى الخشخاش واللوز

من الحلويات التي تحمل ذكريات من الطفولة للكثيرين منا. اخترنا تحضيرها مع مربى الخشاش، هذه الثمرة التي هي أصل الحمضيات. كانت المائدة الفلسطينية تحتفل بموسم الزفر أو الخشخاش بإضافة عصيره إلى الحمص واللحوم والمحاشي، وتحفظه كمؤونة طوال العام من خلال المربى المحضر من لبّ الخشخاش، وشرابه المركز المنعش. مرارته وحموضته الشديدتان قبل الطهي جعلته يُنسى بالتدريج، ويصبح شجرة للزينة أكثر من كونه ثمرة لذيذة مميزة الطعم.

Mabrousheh with Seville Oranges Marmalade

Those jam squares hold childhood memories for many of us. We chose to prepare them for you with a marmalade made from Seville oranges, the heirloom of all citrus. The Palestinian table used to celebrate its season by adding it to all the dishes that require sourness such as Hummus, meats, and rolled vine leaves. It was a staple at the Palestinian pantry for the whole year in the form of concentrated juice, and marmalade jam that is prepared from the white pith of the fruit. Its intense sourness and bitterness before being properly processed and cooked are what probably turned this citrus into a decoration tree, making us forget how our grandparents used it and enjoyed its sublime taste.

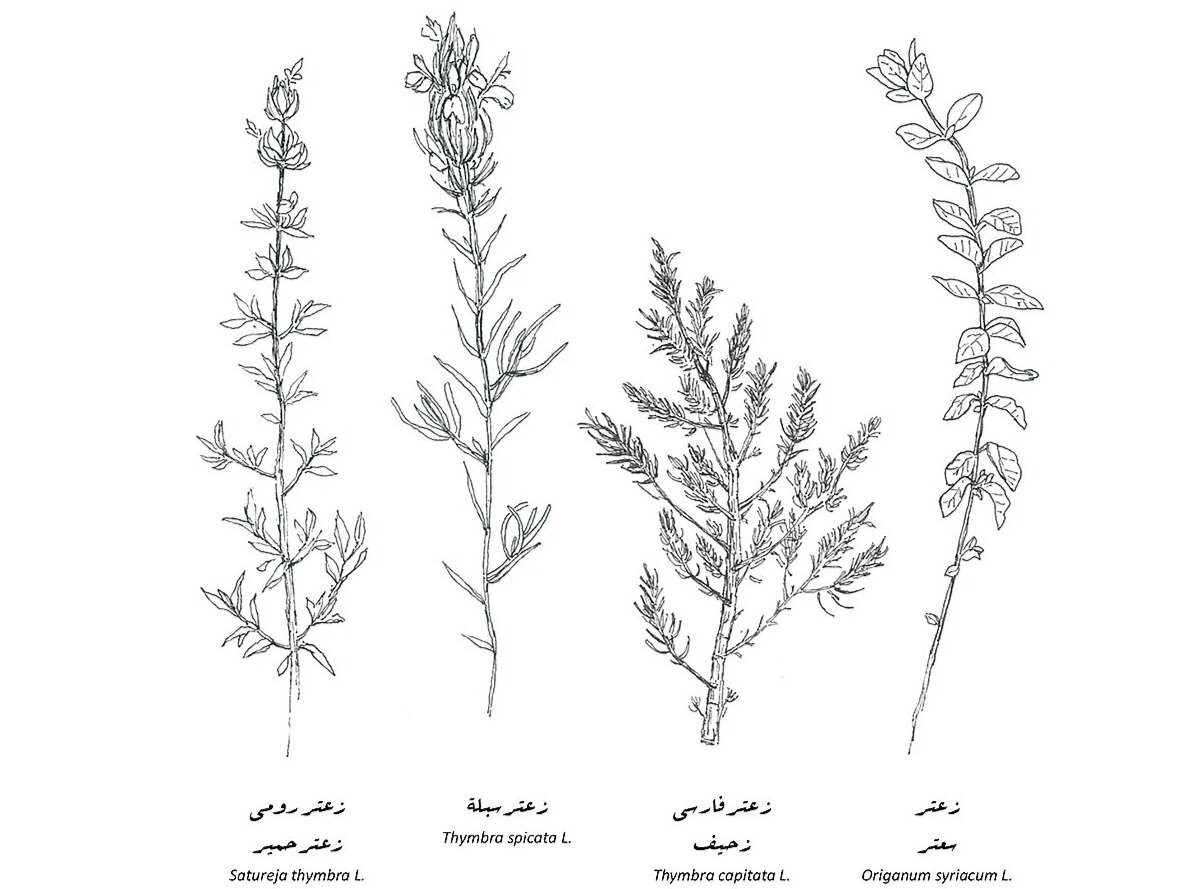

I work with food and I find it beautiful. Everybody loves food! We Arabs love food. But Palestinians always feel a certain bitterness, because we see how the Palestinian kitchen is being appropriated and taken away from us by Israel, which is building its national cuisine out of it: hummus, falafel, couscous, etc. We are not allowed to collect wild herbs like Zaatar, Akub. The Israelis put prohibitions in place not to protect the plants, but in order to create a rupture in the everyday practices of Palestinians going to the land—to prevent the direct connection to the land, the soil. They know that once you break this connection and you render the land an abstract concept, then it will be easier to take it away from the people…to make them forget and settle for easier solutions. But I created this project at a time when there are many young Palestinians who are starting to reclaim land and customs. There are groups working on agriculture, seeds, eco-farming, there are farming co-ops. There is a new kind of consciousness and awareness in the way we are dealing with our bodies on this land, and we feel responsibility in our bodies in a way that was denied to the generation before us.

So I think it was perfect timing for this project… for me in my life but also for the impact that it can have. If you want to talk about disappearing recipes in the middle of a war, it’s not going to work. There are other emergencies. But when you have many groups and individuals creating momentum around certain issues, you’ll get a stronger voice with louder volume.

Nobody can work alone, you know?

When I present a table in Palestine, I focus on one research topic and go deep into it. I create the menu to tell a story based on the research topic and I present it slowly to the people. I perform it as I talk. My menus are made of disappearing recipes and the stories that I bring are almost lost. I bring them from the past, bring them to the table, and observe this encounter. At the same time, I don’t limit myself to the space of the physical table: I am very active on social media and that is also part of the project: activating the archives… creating a narrative of reappearing. For me, it is about reminding Palestinians about what we have lost due to the construction of geography. (For example, each part of the West Bank is secluded from the others, and the people living there cannot go to Gaza, cannot go to Haifa, etc.) There are physical borders that we can’t escape, and the result is people not knowing about each other’s practices. At the same time, the loss of land has made us lose many crops that were central in some recipes that then stopped being cooked. So I bring those stories, not just the recipes. It enables us to look at ourselves in a new way—one that has roots in the past but is also empowering to create change in the future.

So there are the tables in Palestine for Palestinians, and I am also working on tables outside of Palestine, also with a focus on vanishing food practices. Having traveled and shown my work in many different places, I am able to create a narrative that retains its local essence though presented in another place. I find the challenge of addressing diverse audiences exciting.

What I want to achieve is for people to have an encounter with a part of themselves they didn’t know existed.

History, for the longest time, has been written by the nations and gender holding power, which usually eliminates female power from the equation. I do believe that in the last decade there has been more energy going through collective voices to reverse this suppressive narrative and discourse that was never written by the less voiced. But for collectivity to work, each person needs to be aware of themselves as part of the group rather than dissolve into it. The moment we dissolve, it becomes enslavement, leading us to forget ourselves and what we can offer as individuals that is different and unique.

It is a question of equality as well. I believe that collectivity created by women is different than that created by men—the way we cook the food, sit and eat and talk together, the way we communicate and analyze things, the way we respect each other tends to be different than the ways of men. There is less ego in the process and the actions. That’s why for me the kitchen is a space of empowerment. The way we move through it, process and respect the food: we channel energy. So I believe in collectivity but one that is not patriarchal, one that is not selfish, one that does not have a loud voice, is not black and white. It is more tender and simple, it keeps reinventing itself. Our bodies are changing all the time.

We create, share, and love.

~

Mirna Bamieh is an artist from Jerusalem/Palestine with a BA in Psychology from Birzeit University in Ramallah and an MFA in Fine Arts from Bezalel Academy for Arts and Design in Jerusalem. She participated in the Ashkal Alwan Home Workspace program in Beirut as a 2013/14 fellow, and obtained a Diploma in Professional Cooking two years ago—which led her to use storytelling and food as mediums for creating socially engaged projects.

Through her art practice she aspires to create artworks where food/eating/sharing create a fresh, innovative way for people to experience themselves and their surroundings. Projects include: Maskan Apartment Project, Potato Talks Project, and—for the past 3 years—a full focus on Palestine Hosting Society.

Palestine Hosting Society was founded in 2017 as an extension of Bamieh’s artistic practice, which often looks at the politics of disappearance and memory production. It is a live art project that explores traditional food culture in Palestine, especially practices which are on the verge of disappearing, bringing these dishes back to life over dinner tables, talks, walks, and various interventions.

Mirna creates artworks that unpack social concerns and limitations in contemporary political dilemmas and reflect on the conditions that characterize Palestinian communities and beyond.