7 The Great War

In 1914, Europe had been officially “at peace” for nearly a century. However, the official peace covered a growing tension that was beginning to flare up into military conflict. Unification of Germany in 1870, after the Prussian-led victory over the French, had created a new nation with imperial aspirations in the middle of Europe. Bismarck’s new nation competed with neighboring countries in industry, agriculture, and overseas empire-building. The existence of a strong, united Germany ended the careful balance of power created by the Congress of Vienna in its effort to reset the clock and redraw the map after the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. France and Germany were enemies and sought alliances against each other. By 1914, most governments in Europe were preparing for an eventual war between these groups of allied nations, although no one knew what incident would bring the continent to battle. But, as early as 1888, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had predicted that “some damned foolish thing in the Balkans” could initiate a widespread European conflict. He was proven correct on the streets of Sarajevo on June 28, 1914.

During World War One, the principal members of each of these alliances were the “Central Powers”, consisting of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire against the “Allied Powers”, which at the beginning of the war was called the “Triple Entente” after the original allies, France, Great Britain, and Russia. Russia left the war in 1918, Italy joined the allies in 1915, and Japan was an additional ally on the French side. The United States entered the war to support the allies in 1917.

The underlying causes of World War One were nationalism, opposition to foreign rule, and simmering rivalries between the Great Powers that were exacerbated by treaties requiring allies to enter a war once it began. Previously, potential world conflicts had been avoided through negotiation among the Powers. Africa was divided among the European empires at the Berlin Conference in 1885, while “Spheres of Influence” were established in China in order to regulate trade. However, such a “Concert of Nations” did not succeed in the Balkans.

The Balkan conflict Bismarck had predicted began in 1908 with the Austro-Hungarian takeover of Bosnia from the Ottoman Empire. Many Serbs lived in Bosnia, so Serbian nationalists wanted it to be part of Serbia. The Serbs and Bulgarians deepened their alliance with the Russians, who also wanted to check the expanding influence of the Austrians in the Balkans.

The independent nations of the Balkans fell into war in 1912-1913, first with the Ottomans, resulting in an independent Albania, and then with each other as ethnic and religious boundaries were contested. These were bloody conflicts that included attacks on civilian populations in waves of ethnic cleansing—people living in this region would experience similar massacres in the 1990s after the end of the Cold War. The Balkan armies on both sides dug into trenches as new arms and technology limited the movement of troops.

In an effort to strengthen Bosnian ties to Austria, Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand and his wife made an official visit to the regional capital of Sarajevo on June 30, 1914. A secretive Serbian nationalist group, that had been encouraged and supported by Serbian military officers, plotted the assassination of the royal couple as their motorcade made its way through the city. After some initial bungling, one of the conspirators, nineteen-year-old Gavrilo Princip, shot and killed the Archduke and his pregnant wife.

The Austro-Hungarian government made a series of demands for restitution from the Serbian government. When Serbia refused, Austria decided to invade. Germany was bound by its treaty obligations to support any action taken by its ally Austria-Hungary. Austria’s invasion of Serbia activated the European alliance system: Russia sided with the Serbs, France supported Russia, and Great Britain was allied with France.

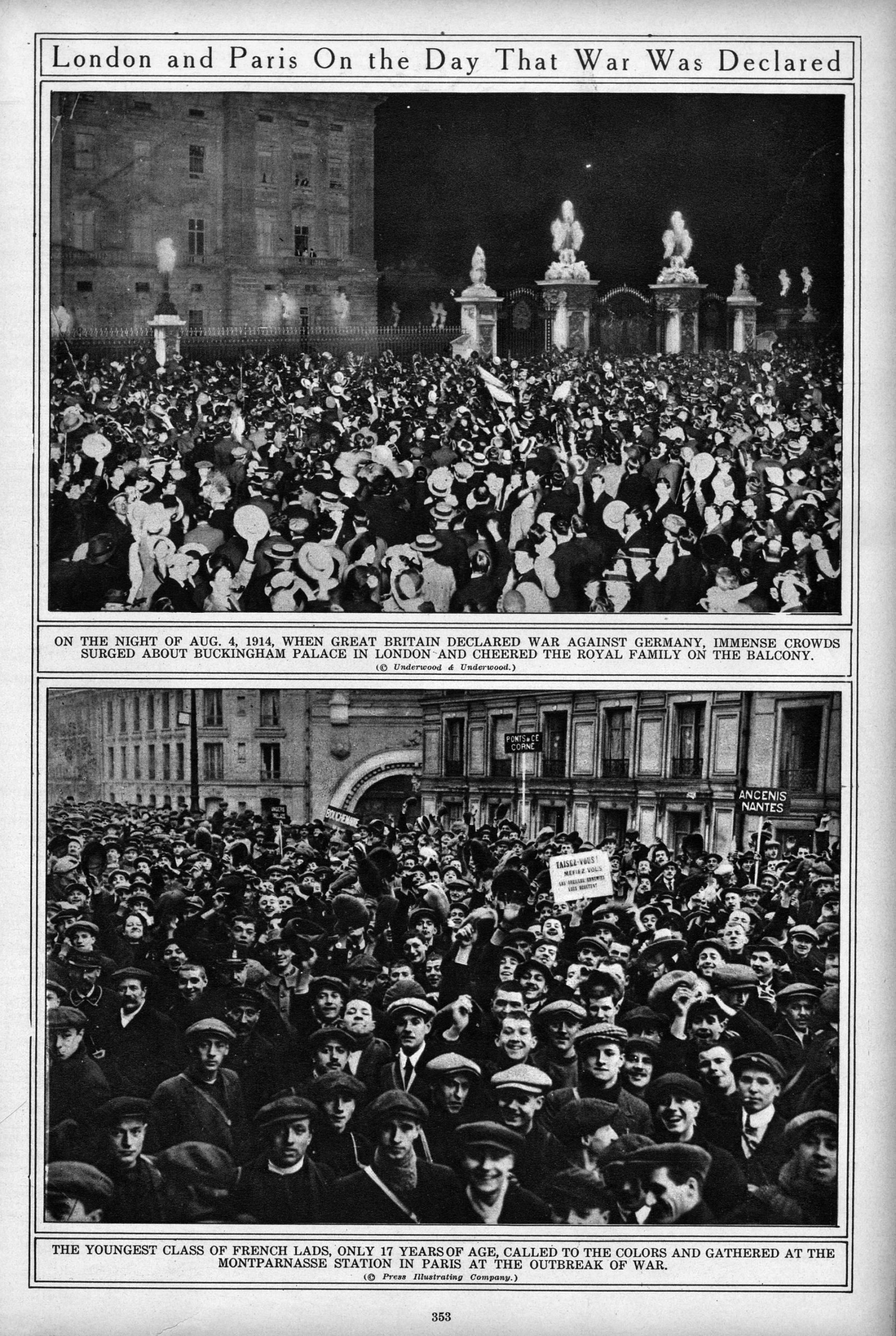

All of Europe’s armies had been preparing for a continent-wide conflict since the unification of Germany in 1870. Most nations required some form of military service from all young men, so that thousands of trained reserve soldiers could be quickly called up. All war plans relied on the quick mobilization of troops, and the extensive European railway network built in the nineteenth century moved regiments more rapidly than in any previous war. This rapid deployment meant that as soon as one side mobilized, the opposing side also had to mobilize in defense. Less time was available for calm decision-making as every nation rushed to arms. In July 1914, when Austria declared war and shelled the Serbian capital, Belgrade, Russia mobilized its military. Germany mobilized against Russia. Russia was allied with France, so France mobilized. Great Britain was allied with France, so Great Britain mobilized. The Ottomans sided with Germany as a counter to Russia. Italy, which had a defensive alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary, sat out of the first months of war, until its government decided to side with France, Great Britain, and Russia in early 1915.

Because of the French-Russian alliance, the Germans knew that they would face a two-front war in any European-wide conflict. Expecting to face enemies on Germany’s eastern and western borders, the German generals had been planning for years to initially fight a defensive war with Russia in the east and an offensive war with France in the west; holding off invading Russian armies while focusing on defeating the French first.

In the first months of the war, the Germans were successful in carrying out their strategy. The German army on the eastern front was able to stop and even defeat the advancing Russians. On the western front, the German government asked permission of neutral Belgium to pass through on their way to a surprise attack on France. When the Belgians rejected the request, German troops invaded and occupied Belgium in August 1914. The Germans advanced rapidly into France, but were halted by combined French and British forces, miles from Paris. Both sides dug in, creating a network of opposing trenches that ultimately extended from the North Sea to the Swiss border. Armies on both sides would be frustrated in their attempts to break through on this “western front” for the next four years.

Advances in military technology caused the stalemate. The wars of the nineteenth century had been mobile, with generals coordinating the movements of infantry foot-soldiers, horse cavalry, and artillery cannons on the battle landscape. However, conflicts like the Crimean War and the U.S. Civil War had begun introducing better, more deadly weapons. The Charge of the Light Brigade had proven that cavalry was ineffective against dug-in artillery. And in the last decades of the nineteenth century, Europeans had perfected the use of machine guns, practicing on native populations in their colonies. By 1914 the armies of Europe had better weapons and better defenses: long-range artillery, machine guns, trenches, and barbed wire. And they were ready to use these on each other, rather than just on the so-called “barbarians” their empires ruled over.

Since neither cavalry nor infantry could stand against machine guns, attacks in trench warfare began with massive artillery barrages to “soften” the other side before troops were sent out of their trenches, “over the top” into the no-man’s land between their trenches and those of the enemy, with fixed bayonets to overwhelm any enemy soldiers who had survived the shelling. When their artillery had not “softened up” the opposing forces enough, attackers would be met with enough machine gun fire to slow down any effective advance. During four long years of war, millions would either be severely wounded or killed in the “no-man’s-land” that separated the opposing armies.

Frustrated with the stalemate of trench warfare, the opposing sides on the western front tried new technologies and strategies in search of a decisive victory. Airplanes, first developed by the Wright Brothers in 1903, proved their value in reconnaissance and later in strafing trenches with machine guns and dropping small bombs. Early radios allowed aviators to coordinate with ground controllers. And in the spring of 1915, the Germans first experimented using poison gas on the battlefield. Within months, all sides would develop different varieties of poison gas, while racing to improve the designs of their gas masks. Poison gases added another devastating weapon to trench warfare, while achieving no significant advantage. At least 1.3 million people were killed by gas attacks. Chlorine and mustard gas were two of the most common chemical weapons used by both sides in the war. In the case of mustard gas poisoning, the effects took 24 hours to begin and it could take four to five weeks to die.

Airplanes and poison gas, alongside machine guns and massive artillery, simply became more cogs in the war’s increasingly-effective killing machines. More people were killed, but without any change in the outcome of the war. Enormous battles raged for months at a time at Verdun and the Somme in 1916, resulting in millions of casualties but hardly any territorial changes.

The conflict on the Eastern Front, where the Germans and Austro-Hungarians faced the Russians, was more mobile. In 1916, as the months-long Battle of Verdun seemed to be going against the French, the Russian Army overwhelmed Austrian forces in the Brusilov Offensive, the largest and most deadly of the war. Hundreds of thousands died on both sides as the Russian army advanced, forcing the Germans to divert their forces from the Western Front. Austro-Hungarian offensive capabilities were largely destroyed, but Russian soldiers were also disillusioned and began to seriously question the competence and decisions of their officers and commanders, including the Tsar himself.

Even before the entry of the United States in 1918, the war had become truly global. Japan was eager to be counted as a world power, and Japanese leaders seized upon the opportunity the war provided to improve their status in Asia. After taking control of German colonies in China and the Pacific in 1914, Japan sent the Chinese government a list of 21 Demands. The Chinese believed that giving in to Japan’s demands would have basically resulted in China becoming a colony of the Japanese Empire. The Chinese government agreed to some of the demands, but leaked the list to British diplomats, who intervened to prevent a complete shift in the balance of power in Asia.

In Africa, Germany lost its colonies in the fighting. The German commander in East Africa, led a largely native African force in guerrilla tactics against Allied troops for most of the war. In eastern Africa, disrupted crop cultivation and led to hundreds of thousands of deaths by starvation and disease.

The Ottoman Empire controlled territory on either side of Bosporus straits, which connect the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. In 1915, the Allies landed troops at Gallipoli, a peninsula on the European side of the Bosporus, about 200 miles (320 km) from the Ottoman capital in Istanbul The plan was to take Istanbul, knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war and open a third front against Austria-Hungary and Germany through the Balkans. However, the Turks held the high ground above the landing site chosen for the mostly colonial troops. Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) troops were decimated, in a battle that marks the beginning of a sense of nationality in those countries. The anniversary of the Gallipoli landing, April 25th, is still celebrated as ANZAC Day. The disastrous plan nearly ended the political career of the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill.

The eleven month-long Gallipoli invasion was even more important for the Turks. The hard-fought victory was led by General Mustafa Kemal, who soon became a national hero and would go on to found the modern Turkish Republic and serve as its first president after the war. However, at nearly the same time as the Gallipoli landings, the Ottoman government also decided to take action against the Christian minority in Armenia. Armenians had suffered from periodic pogroms in the decades preceding World War One. The Armenians were loyal subjects (many were serving in the army when the persecution began), but after an unsuccessful Russian attempt to invade Turkey from the east, some military leaders in the Turkish government accused the Armenians of collaborating with the Russian troops and decided to eliminate the Armenian population. Men were executed, while women and children were force-marched across the desert to Mesopotamia. Nearly one million died in what was the worst genocide of the 20th century before the Holocaust of World War Two.

The imperial powers drafted soldiers from their colonies into the fight. Many of the 18 million people killed in battle and 23 million wounded, were people ruled by the empires. The French brought in African troops from Senegal and Morocco, who fought and died in the trenches of Western Front alongside other Allied soldiers. British imperial subjects like the Canadians, Australians, and New Zealanders fought beside their English cousins. Over 700,000 Indians fought for Britain against the Ottomans in Mesopotamia. Indian divisions were also sent to Gallipoli, Egypt, German East Africa, and Europe. At least 74,000 Indians died in World War One.

Despite all of the efforts for a breakthrough on the battlefields of France and Eastern Europe, the most effective strategy against Germany was the British-led naval blockade, which cut off grain and other food supplies from overseas. The Germans, who had developed the most effective submarines and torpedoes, tried to blockade Great Britain and France by sinking incoming supply ships. This German naval strategy, however, risked bringing the United States into the war. After the sinking of the passenger ship Lusitania in May 1915, when a hundred U.S. citizens were drowned a few miles from the Irish coast, some American public opinion began to shift in favor of entering the conflict. The German government quickly backed away from unrestricted submarine warfare against supply ships bound for the Great Britain and France. Woodrow Wilson ran for re-election in 1916 on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.” But only a month after his second inauguration, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917.

Wilson’s request for a declaration of war followed just a few days after Russia’s withdrawal from the conflict. The third year of the war saw a major change in German military prospects when the Romanov Dynasty of Tsar Nicholas II collapsed in March 1917. The trouble had begun in late February with a strike by women factory workers in St. Petersburg. 90,000 women took to the streets shouting “Bread!”, “Down with the autocracy!”, and “Stop the war!” The following day, over 150,000 men and women marched and a general strike began. Within a few days the army had sided with the revolutionaries and Nicholas II was forced to abdicate.

Liberal reformers soon established a republic, which actually made it easier for U.S. President Wilson to proclaim that the war was to “make the world safe for democracy,” since a major ally was no longer ruled by an absolute monarch. However, the democratic reformers in Russia were not as well organized as socialist revolutionaries led by Vladimir Lenin, who saw the end of tsarist rule as an opportunity to also defeat capitalism and creating a “dictatorship of the proletariat”. The revolutionaries and the soldier and sailors who supported them wanted to end Russian participation in the war.

By the fall, the socialist revolutionaries, called Bolsheviks, established workers’ and soldiers’ councils—“soviets”—in the major cities. In November 1917, overthrew the fledging republic to establish a revolutionary socialist state under the leadership of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who began to call themselves the Communist Party. Lenin, confident that his revolution would soon inspire oppressed workers everywhere to overthrow capitalism, quickly negotiated a peace with Germany in March 1918, ceding much of Russia’s western territories, including Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine, losing 34% of the former Russian Empire’s population and most of the industrial base. The treaty also called for territories claimed by the Ottoman Empire to be handed over to Germany’s ally, but Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia declared their independence instead. Russia also agreed to pay 6 billion marks to compensate Germany for its losses.

The Russian revolution soon became a civil war between the “Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army”, formed by the Bolshevik leader Leon Trotsky, and the armies of the “White Russians” under several leaders, dedicated to restoring the Tsarist monarchy. To prevent the return of the Romanovs to power, the revolutionaries had the entire family killed in July, 1918. The revolutionaries also waged war on uncooperative peasants called Kulaks, whom they accused of withholding grain from the Bolshevik government. Many of the Kulaks were Ukrainian, which contributed to an ongoing aggression toward the Ukraine by the new Soviet Union.

Even after World War One ended, the Allies, including the United States, supported the White Russians against the Bolsheviks, sending thousands of troops to support the counterrevolutionaries in Siberia between 1918 and 1920. Years later Josef Stalin, who fought on the Soviet side in the civil war, would remember this fact while negotiating with Britain and the U.S. during World War II

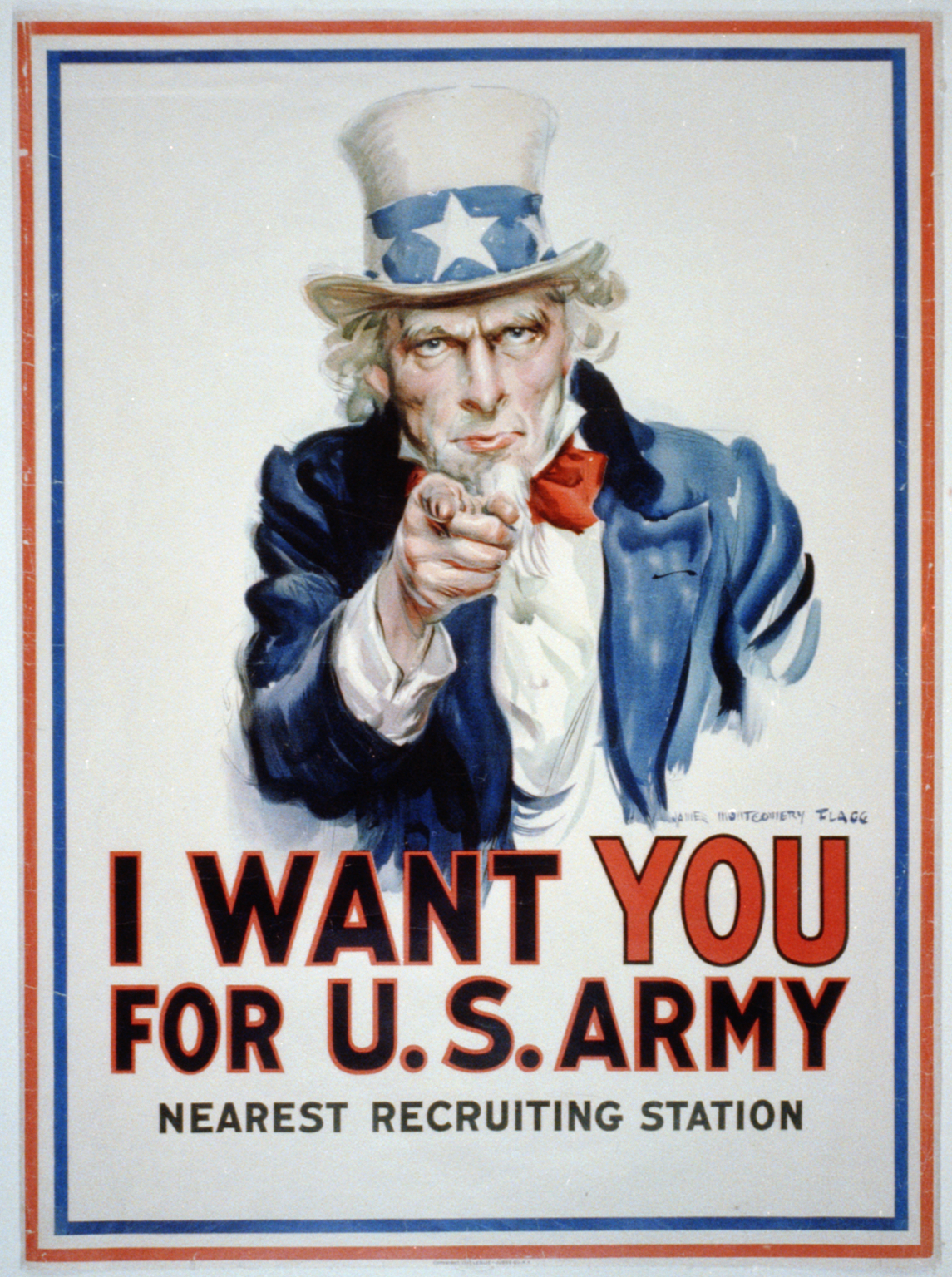

The European powers struggled to adapt to the brutality of modern war, with its advanced artillery, machine guns, poison gas, and submarines. Until the spring of 1917, the Allies possessed few effective defensive measures against German submarine attacks, which had sunk more than a thousand ships by the time the United States entered the war. The rapid addition of American naval escorts to the British surface fleet and the establishment of a convoy system countered much of the effect of German submarines. Shipping and military losses declined rapidly, just as the American army arrived in Europe in large numbers. Although many of the supplies still needed to make the transatlantic passage, the physical presence of the army proved to be a fatal blow to German plans to dominate the Western Front.

The European powers struggled to adapt to the brutality of modern war, with its advanced artillery, machine guns, poison gas, and submarines. Until the spring of 1917, the Allies possessed few effective defensive measures against German submarine attacks, which had sunk more than a thousand ships by the time the United States entered the war. The rapid addition of American naval escorts to the British surface fleet and the establishment of a convoy system countered much of the effect of German submarines. Shipping and military losses declined rapidly, just as the American army arrived in Europe in large numbers. Although many of the supplies still needed to make the transatlantic passage, the physical presence of the army proved to be a fatal blow to German plans to dominate the Western Front.

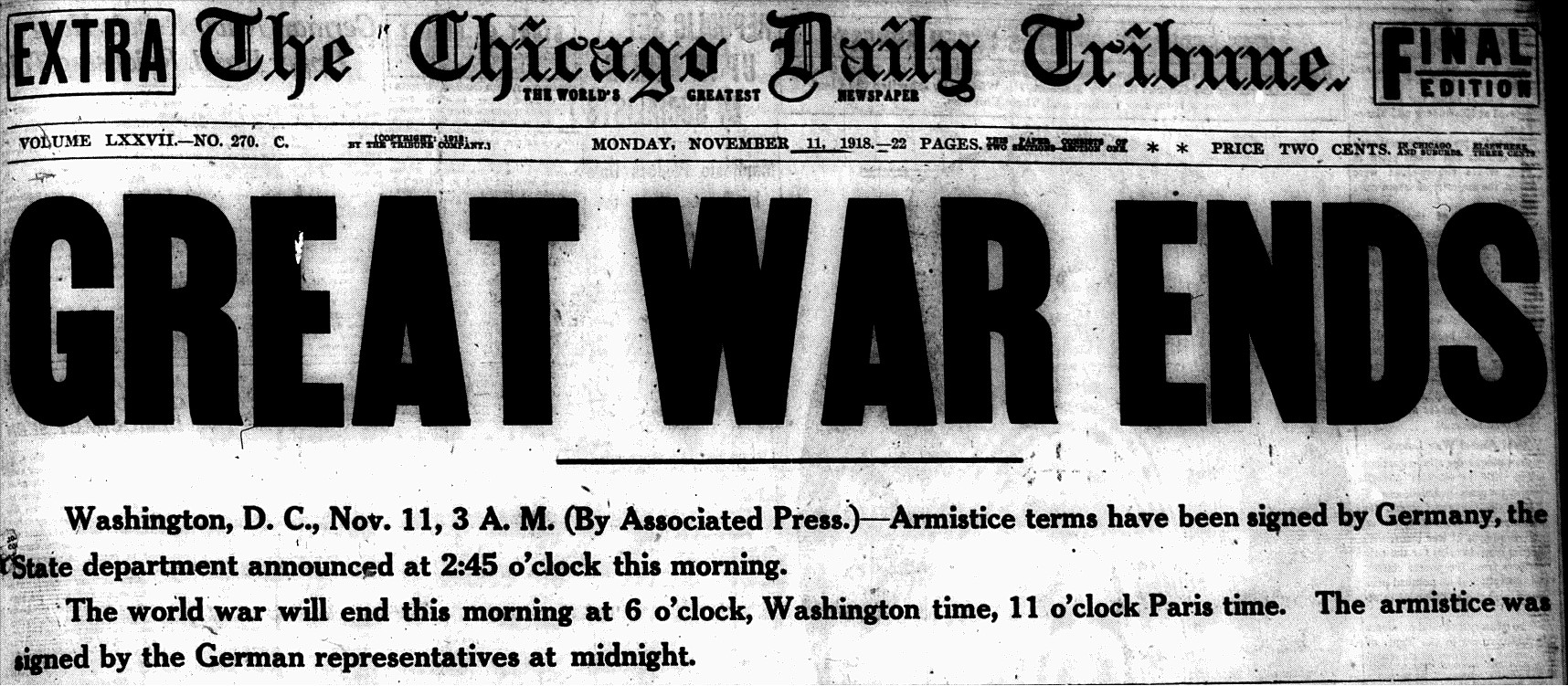

In March 1918, Germany tried to take advantage of the withdrawal of Russia and its new single-front war before the Americans arrived, with the Kaiserschlacht (Spring Offensive), a series of five major attacks. By the middle of July 1918, each and every one had failed to break through the Western Front. Then, on August 8, 1918, two million men of the American Expeditionary Forces joined the British and French armies in a series of successful counteroffensives that pushed the disintegrating German lines back across France. The gamble of the Spring Offensive had exhausted Germany’s military, making defeat inevitable. Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated at the request of the German military leaders and a new democratic government agreed to an armistice on November 11, 1918, hoping that by embracing Wilson’s call for democracy, Germany would be treated more fairly in the peace talks. German military forces withdrew from France and Belgium and returned to a Germany teetering on the brink of chaos. November 11 is still commemorated by the Allies as Armistice Day (called Veterans’ Day in the United States).

In all between 16 and 19 million soldiers died in World War I along with 7 to 8 million civilians (before the influenza pandemic of 1919). Some of the worst battles were:

- Verdun: 976,000 casualties (Feb.-Dec. 1916)

- Brusilov Offensive: Nearly 2,000,000 casualties (June-Sept. 1916)

- Somme: 1,219,201 casualties (July-Nov. 1916)

- Passchendaele: 848,614 casualties (July-Nov. 1917)

- Spring Offensive: 1,539,715 casualties (March 1918)

- 100 Days Offensive: 1,855,369 casualties (Aug.-Nov. 1918)

Civilian populations were also targeted. While bombing cities from airplanes was much more common in World War II, naval blockades were also an effective way of putting pressure on civilians. Even if a nation was relatively self-sufficient in food production under normal circumstances, war was not a normal circumstance. The British blockade of Germany prevented not only war supplies but food from reaching the German people, resulting in a half million civilian deaths. For the Europeans, World War One was a “Total War” involving every level of society.

By the end of the war, more than 4.7 million American men had served in all branches of the military. The United States lost over one hundred thousand men, fifty-three thousand dying in battle and even more from disease. Their terrible sacrifice, however, paled before the European death toll. After four years of stalemate and brutal trench warfare, France had suffered almost a million and a half military dead and Germany even more. Both nations lost about 4 percent of their populations to the war. And death was not nearly done.

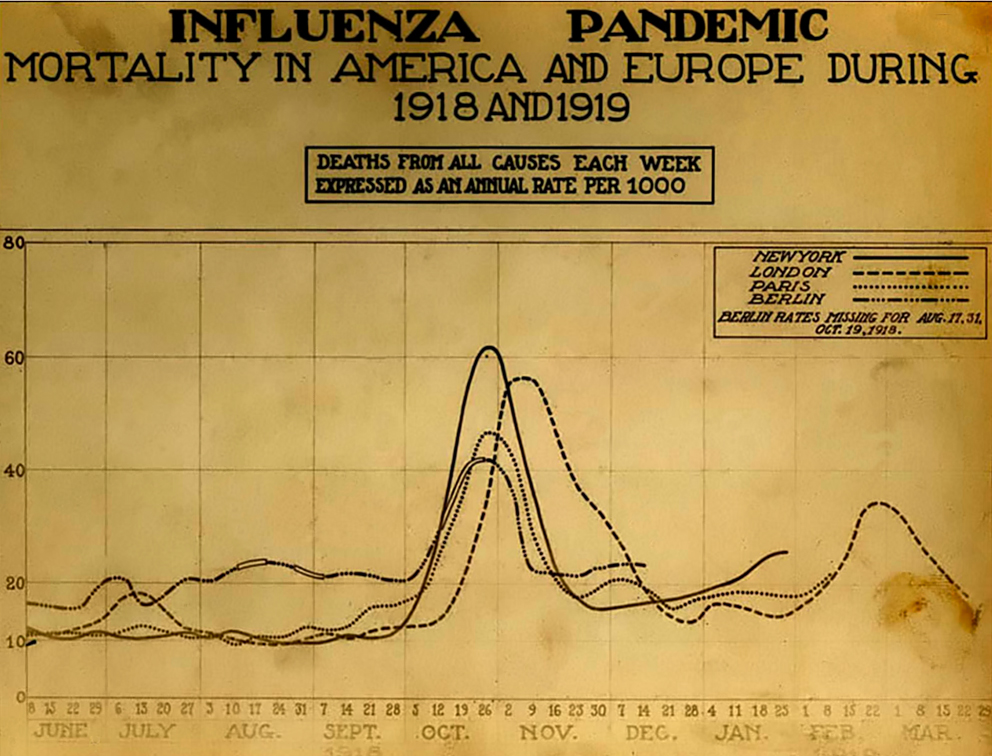

Even as war raged on the Western Front, an even deadlier threat loomed. In the spring of 1918, a new strain (H1N1) of the influenza virus appeared in the farm country of Kansas and hit nearby Camp Funston, one of the largest army training camps in the nation. The virus spread like wildfire. Between March and May 1918, fourteen of the largest American military training camps reported outbreaks of influenza. Some of the infected soldiers carried the virus on troop transports to France. By September 1918, influenza had spread to all training camps in the United States.

The second wave of the virus was even deadlier than the first. Unlike most flu viruses, the H1N1 strain struck down those in the prime of their lives rather than old people and young children. A disproportionate number of influenza victims were between ages eighteen and thirty-five. In Europe, influenza hit troops and civilians on both sides of the Western Front. The disease was misnamed “Spanish Influenza,” due to accounts of the disease that first appeared in the uncensored newspapers of neutral Spain while the warring nations tried to suppress the news of disease for propaganda purposes.

The second wave of the virus was even deadlier than the first. Unlike most flu viruses, the H1N1 strain struck down those in the prime of their lives rather than old people and young children. A disproportionate number of influenza victims were between ages eighteen and thirty-five. In Europe, influenza hit troops and civilians on both sides of the Western Front. The disease was misnamed “Spanish Influenza,” due to accounts of the disease that first appeared in the uncensored newspapers of neutral Spain while the warring nations tried to suppress the news of disease for propaganda purposes.

The “Spanish Flu” infected about 500 million people worldwide and resulted in the deaths of between fifty and a hundred million people; possibly more. World population in 1918 was about 1.8 billion; influenza infected nearly a third and killed between 5% and 10%. Reports from the surgeon general of the army revealed that while 227,000 American soldiers had been hospitalized from wounds received in battle, almost half a million suffered from influenza. The worst part of the wartime epidemic struck during the height of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1918 and weakened the combat capabilities of both the American and German armies. During the war, more soldiers died from influenza than combat. But the pandemic continued to spread after the armistice, with a death toll of nearly 20% of those infected, as opposed to about 0.1% in regular flu epidemics. Four waves of worldwide infection spread before cases and deaths finally began fading in the early 1920s. No cure was ever found.

The war brought an abrupt end to four great European imperial powers. The German, Russian, Austrian-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires each evaporated and the map of Europe was redrawn to accommodate new independent nations. As part of the armistice, Allied forces occupied territories in the Rhineland separating Germany and France, to prevent conflicts there from reigniting war. A new German government disarmed while Wilson and other Allied leaders gathered in France at Versailles to dictate the terms of a settlement to the war. After months of deliberation, the Treaty of Versailles officially ended the war.

The Great War transformed the world. The Middle East, especially, was drastically changed. Before the war, the region east of the Mediterranean had three main centers of power: the Ottoman Empire, British-controlled Egypt, and Iran. President Wilson’s call for self-determination in the Fourteen Points appealed to many under Ottoman rule, especially the Arabs. In the aftermath of the war, Wilson sent a commission to determine the conditions and aspirations of the people. The King-Crane Commission found that most favored an independent state free of European control. However, the people’s wishes were largely ignored and the lands of the former Ottoman Empire were divided into several nations created by Great Britain and France with little regard to ethnic realities. The British in particular wanted to continue to control the Suez Canal which was their route to India, and to monopolize the oil of the Persian Gulf to fuel the diesel engines of their navy and merchant marine.

The Arab provinces of the Ottomans were to be ruled by Britain and France as “mandates” and a new nation of Turkey emerged in the former Ottoman heartland in Anatolia. According to the League of Nations, mandates were necessary in regions that “were inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world.” Though supposedly established for the benefit of the Middle Eastern people, the mandate system was essentially a reimagined form of nineteenth-century imperialism. France received Syria; Britain took control of Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan (Jordan). The United States was asked to become a mandate power but declined.

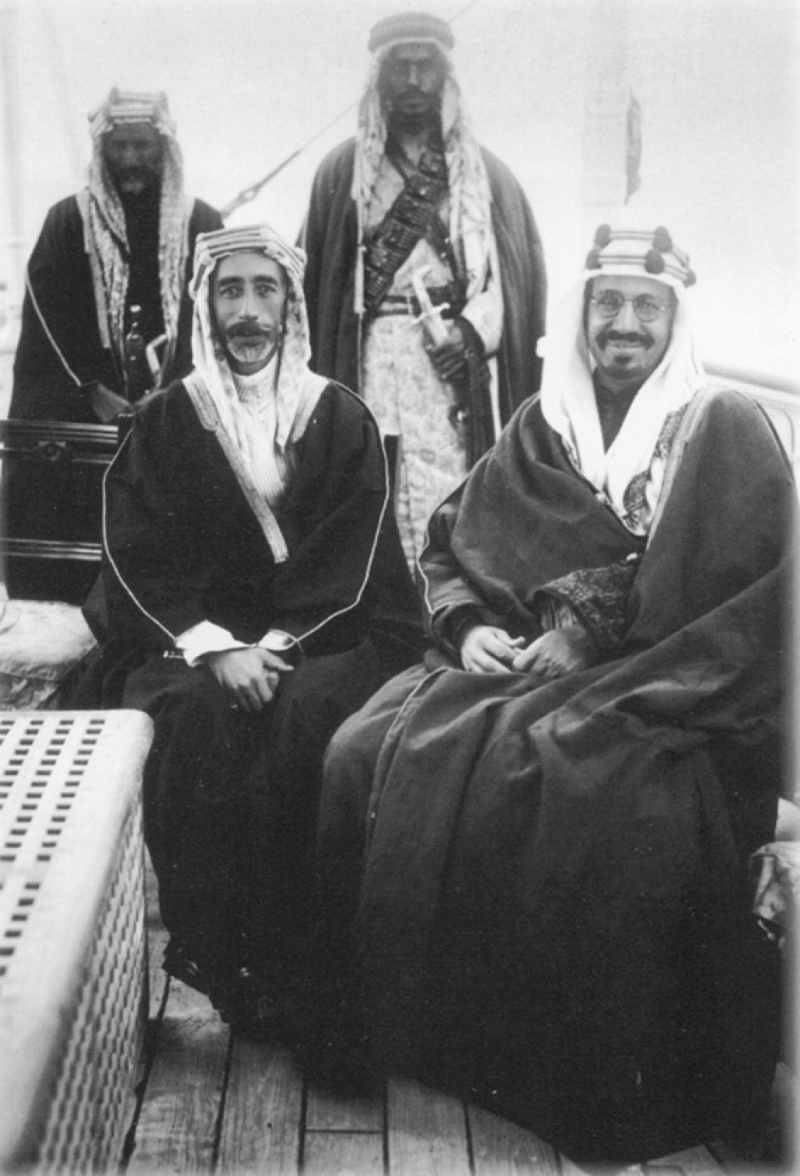

To consolidate their power over the Arabs, the British supported Hussein Ibn Ali (related distantly to the Prophet Muhammad) as king of Hejaz on the Arabian Peninsula, including the holy sites of Mecca and Medina, in 1916. His sons Abdullah and Faisal were chosen to be kings of Transjordan and of Syria, where Faisal was rejected and so instead became the king of Iraq. The Iraqi dynasty ended in violence with the murder of Faisal’s grandson in 1958, but Abdullah’s dynasty still rules Jordan, under Abdullah II and Queen Rania. In Hejaz, Hussein Ibn Ali was overthrown in 1925 by Ibn Saud, a tribal leader from eastern Arabia. Through strategic marriages with other tribes, Ibn Saud established Saudi Arabia. He had so many children that the current king is still one of his many sons.

The disposition of the Middle East was complicated by the increasing importance of its oil resources. Oil had been discovered in Iran in 1908, and during the period when petroleum was becoming the most important commodity of the twentieth century it was also becoming clear that some of the world’s largest reserves were located in the Middle East. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company (now known as BP) was established in 1908 to control production in Iran. After the war, British-controlled businesses that had been licensed by the Ottomans to develop oil discovered in Mesopotamia spurred British interest in creating the new Kingdom of Iraq under British mandate in 1920. The British-controlled multinational, TPC (Turkish Petroleum Company, established in 1912), received a 75-year concession to develop Iraq’s oil.

However, in 1933 when enormous deposits of oil were discovered in eastern Arabia, Ibn Saud turned to the Americans rather than the British to exploit these oil deposits, fearing renewed British meddling in his country. U.S. oil companies have been there ever since.

The movement to establish a Jewish Homeland—Zionism—was begun in the 1890s by Jewish Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl. Shocked by how Jews were being persecuted throughout Europe, even in liberal France, Herzl concluded that Jews would never be fully accepted as citizens anywhere and that they needed to establish a separate Jewish homeland. After some debate, his movement decided to begin buying land in Palestine, the site of the ancient Hebrew kingdom. Originally, most Jews around the world, especially more religious Jews, rejected the movement because they believed that Jews were not to return to Israel until the Messiah came. Zionists in Palestine often had problems with their Arab neighbors, who looked upon these new arrivals as Europeans trying to take over their country.

In the heat of the war, in 1917, the British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour promised that Palestine would be recognized as a “Jewish homeland,” in an attempt to gain support of Jews among the belligerents—not realizing that Zionism was hardly the majority view at that time within Judaism. Of course, the British also promised to respect Arab sovereignty in Palestine; setting the stage for conflict in the region that has continued to today.

Media Attributions

- Periscope_rifle_Gallipoli_1915

- 2880px-Map_Europe_alliances_1914-en.svg

- DC-1914-27-d-Sarajevo-cropped

- 1920px-The_War_of_the_Nations_WW1_337

- German_soldiers_in_a_railroad_car_on_the_way_to_the_front_during_early_World_War_I,_taken_in_1914._Taken_from_greatwar.nl_site

- Aerial_view_Loos-Hulluch_trench_system_July_1917

- FirstSerbianArmedPlane1915

- Nach_Gasangriff_1917

- Battle_of_Tsingtao_Japanese_Landing

- lossy-page1-2880px-Scene_just_before_the_evacuation_at_Anzac._Australian_troops_charging_near_a_Turkish_trench._When_they_got_there_the…_-_NARA_-_533108.tif

- 2880px-Ambassador_Morgenthau’s_Story_p314

- Indian_bicycle_troops_Somme_1916_IWM_Q_3983

- Tov_lenin_ochishchaet

- Uncle_sam_propaganda_in_ww1

- Western_front_Kaiser_in_trench_1918-04-04

- 2880px-Emergency_hospital_during_Influenza_epidemic,_Camp_Funston,_Kansas_-_NCP_1603

- Spanish_flu_death_chart

- 2560px-MPK1-426_Sykes_Picot_Agreement_Map_signed_8_May_1916

- King_Faisal_I_of_Syria_with_King_Abdul-Aziz_of_Saudi_Arabia_in_the_mid-1920s

- PikiWiki_Israel_7188_Herzl_on_board_reaching_the_shores_of_Palestine