11 Cold War

When we think of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, we typically imagine the thousands of nuclear missiles each nation pointed toward the other and of a clash of ideologies as communism and capitalism battled for world supremacy. A defining element of the Cold War was that it did not become a hot war. Neither the U.S. not the U.S.S.R. launched attacks on the territories of the other. Instead, the superpowers supported or intervened in the conflicts of nations in their spheres of influence. To a great extent, the Cold War was a struggle by each superpower to extend its sphere of influence and block the other from doing the same. The Soviets and the Americans justified their actions in a variety of ways. Creating a buffer-zone to protect the homeland. Defending like-minded governments against a different political or economic philosophy. One side said it was protecting the world from the threat of totalitarian communist imperialism and the other said it was protecting the world from imperialist capitalism. Interestingly, both accused their antagonist of being an empire.

World War Two in Europe was nearly over when Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill met at Yalta in February 1945, but the war in the Pacific was still ongoing. This fact weighed heavily on the British and Americans, who were hoping for Soviet help in defeating Japan. Stalin had signed a Non-Aggression Pact with the Japanese in 1941, which both sides maintained during the conflict; at Yalta, he pledged to declare war on Japan three months after the German surrender. In exchange, Roosevelt and Churchill essentially agreed to the Soviet military occupation of Eastern Europe. It would turn out that this would be the beginning of the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, which would not be fought directly between the two superpowers, but rather through proxy wars in the developing world over most of the next five decades.

World War II in Europe was nearly over when Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill met at Yalta in February 1945, but the war in the Pacific was still unresolved. Stalin had signed a Non-Aggression Pact with Japan in 1941 which both sides had maintained during the conflict. Roosevelt and Churchill urged Stalin to join them in defeating Germany’s final Axis partner. Stalin agreed to declare war on Japan three months after the German surrender. In exchange, Roosevelt and Churchill essentially agreed to accept the Soviet military occupation of eastern Europe. The Allies were interested in winning the Second World War, but were all aware that they were not natural allies in the long run. After the war’s end, Eastern Europe and Asia would both be areas of contention between the U.S.S.R. and the “West”.

Despite promised democratic elections, by 1949 the Soviets had set up one-party communist states mirroring their own in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria. Stalin’s desire to dominate eastern Europe as a buffer zone against attacks from the West was understandable, given the history of European wars and the tremendous sacrifices of blood and treasure by the Soviets during the war that had just ended. Stalin also decided to retain the Polish territory first taken by his armies in 1939 when he had been Hitler’s ally and advocated pushing the borders of Poland farther west and south into what had been Germany in 1939. And the Baltic states the Red Army had conquered in 1939-1940 while Hitler was attacking France also remained part of the Soviet Union.

The first Cold War challenge to post-war peace occurred in Greece, where communist and non-communist anti-Nazi partisans began fighting for control shortly after the Germans withdrew from their country in late 1944. When the war ended, this conflict soon turned into a full-blown civil war. However, Greece was outside of the Stalin’s sphere of influence. The British and Americans began supporting the beleaguered parliamentary monarchy against the communists, who were defeated in 1947. The conflict in Greece showcased the new “Truman Doctrine” of containment, under which the U.S. was willing to concede to Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, but would “contain” the spread of communist regimes in any other country.

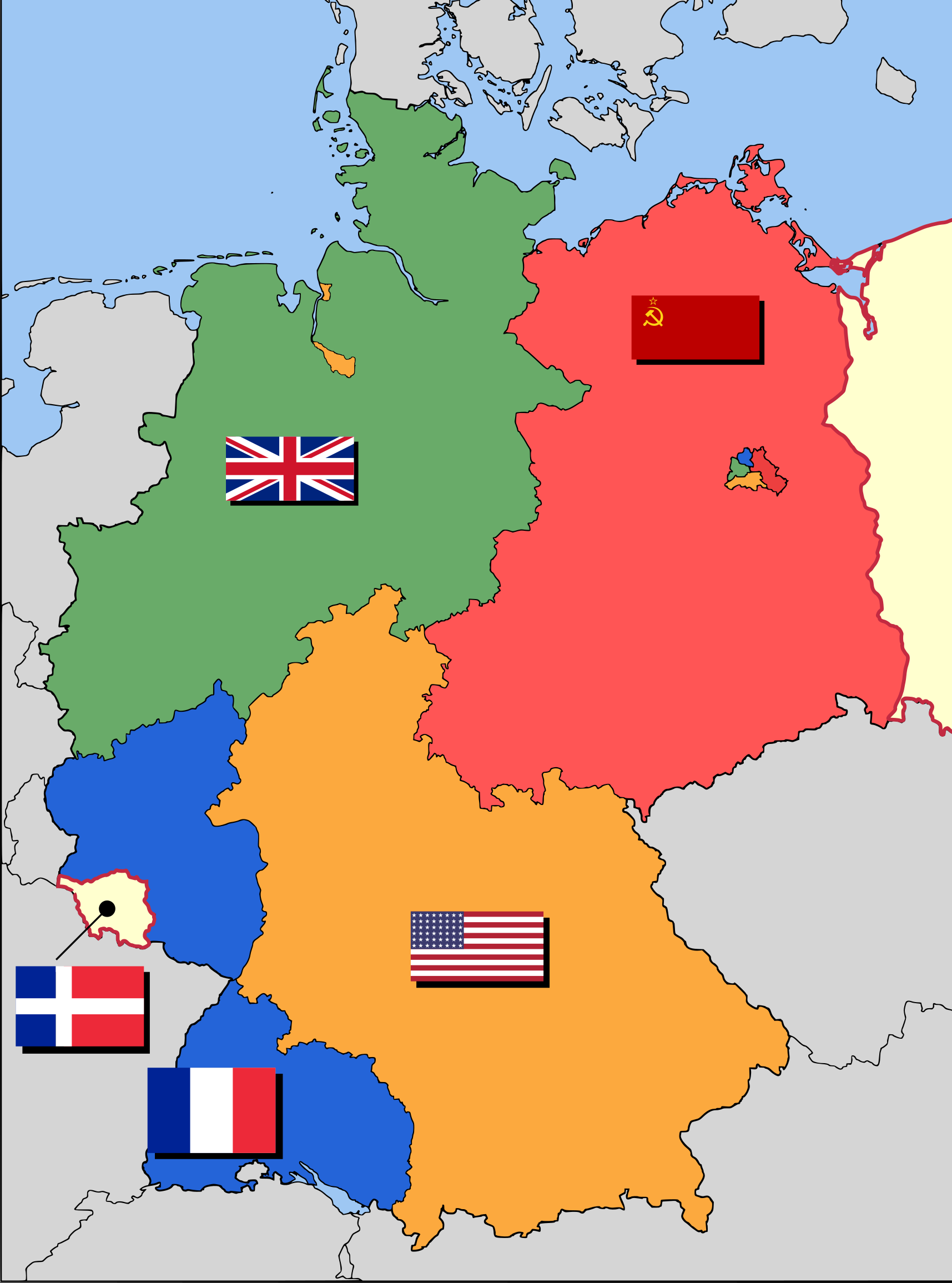

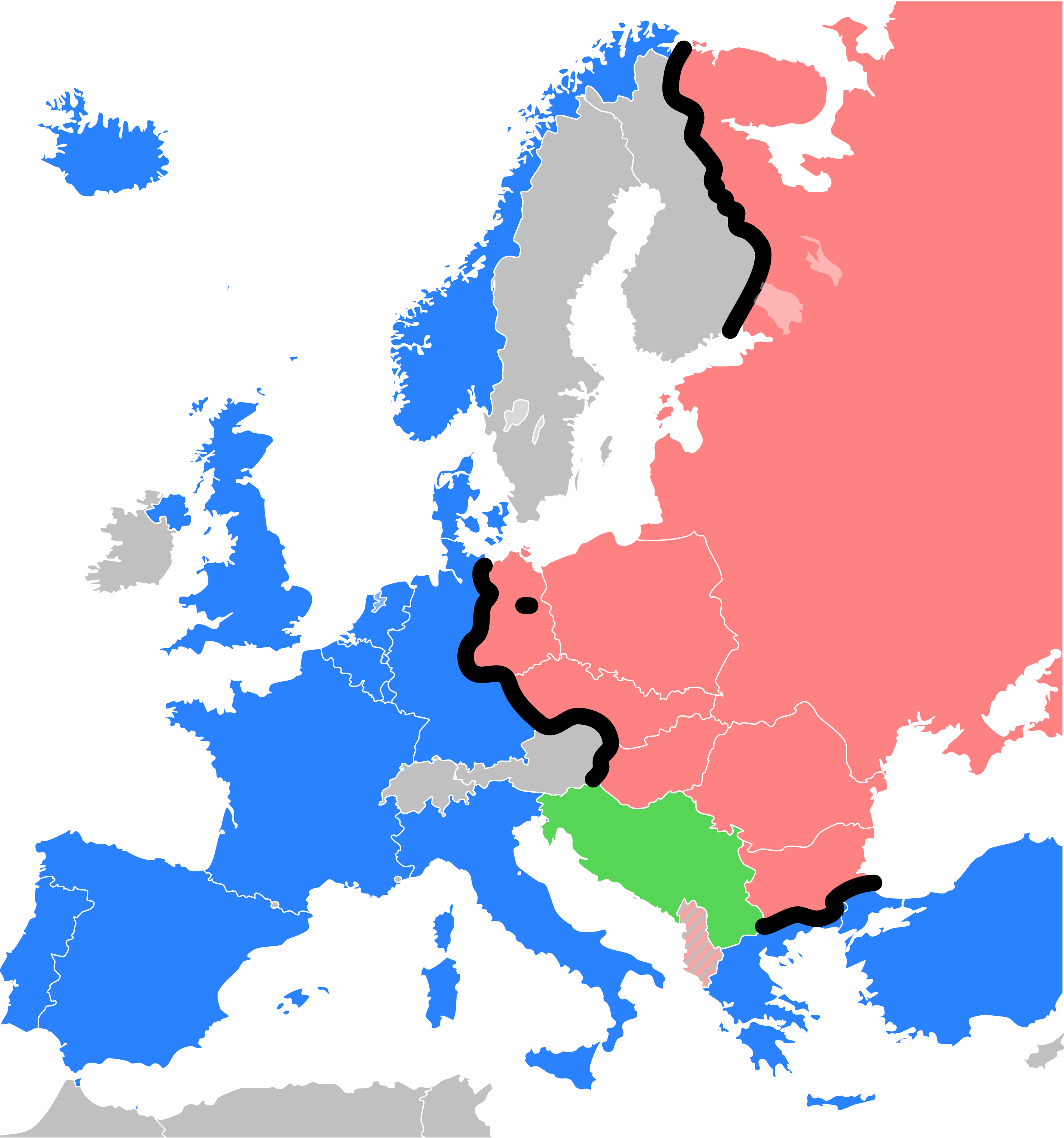

In 1946, former Prime Minister Winston Churchill visited President Harry Truman in his home state of Missouri and made a speech at Westminster College. Churchill said the situation in Europe felt as if Stalin had dropped an “iron curtain” separating East from West. It was an apt description: neither the Soviets nor the new communist regimes permitted free travel between the two sides. The division of. Europe into East and West was complicated by the Allied agreement to occupy defeated Germany in four sectors: U.S., British, French, and Soviet. The German capital Berlin was also divided into quarters by the four former allies, even though it was surrounded by Soviet-occupied East Germany. The division of Germany was completed when the western portion uniting in a federal republic, the Bundesrepublik Deutschland (GDR), in October 1949, complete with elections and multiple political parties. At the same time, East Germany became the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR), a one-party communist satellite state of the Soviet Union. I remember as a child being confused when I listened to the news, why America was enemies with a nation that had Democratic in its name.

Although the United States and the Soviet Union had been allies in World War II, the relationship did not last long after the defeat of Germany and Japan. In February 1946, less than a year after the end of the war, the head of the U.S. embassy in Moscow, George Kennan, sent a message that became known as the long telegram to the State Department denouncing the Soviet Union. Although Kennan’s main point was that the Soviet Union was interested in expanding its worldwide power, he made his argument in the form of an attack on communism which became a regular element of Cold War rhetoric. “World communism is like a malignant parasite which feeds only on diseased tissue,” Kennan wrote, and “the steady advance of uneasy Russian nationalism . . . is more dangerous and insidious than ever before.”

Kennan argued that Russian imperialism had not ended with the Russian empire and under the Soviets would advance under what he called the “new guise of international Marxism”, although the U.S.S.R. was being ruled not as a communist democracy but as a totalitarian dictatorship under Josef Stalin. Marx’s ideal of a “dictatorship of the proletariat”, where workers would live together in such harmony that police and armies would be unnecessary, never arrived for the Russian people. There could be no cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union, Kennan wrote. Instead, the Soviets had to be “contained.” As the Russians had advanced toward Germany in the final years of World War II, they had not only retaken Russian territory but had held onto the lands Stalin had conquered when he was Hitler’s ally and expanded their control over Eastern Europe. In the years after the war the U.S.S.R. controlled not only East Germany but newly formed People’s Republics of Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania. In the alarm caused by the creation of these satellite states, often ruled by Soviet-installed dictators, anti-Soviet sentiment seized the American government and soon the American people.

To try to prevent a drift toward socialism in nations struggling with food shortages and rebuilding from the destruction of the war, the United States launched the Marshall Plan in 1948 to rebuild western Europe. The Soviets responded to the $15 billion aid program with an order that their satellite nations reject it, because the financial assistance came with the condition of economic cooperation that Stalin worried would make small nations like Yugoslavia dependent on western corporations. The United States was anxious to rebuild Europe as quickly as possible, no only to reopen markets for U.S. goods, but also to counter the influence of growing communist parties in Italy, France, and other Western European countries. U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall shipped food and other material aid, and provided financial support to any European country who requested it. The result was the largely capitalist rebuilding of Western Europe and West Germany, while Eastern Europe began industrializing by following Soviet-inspired Five-Year Plans.

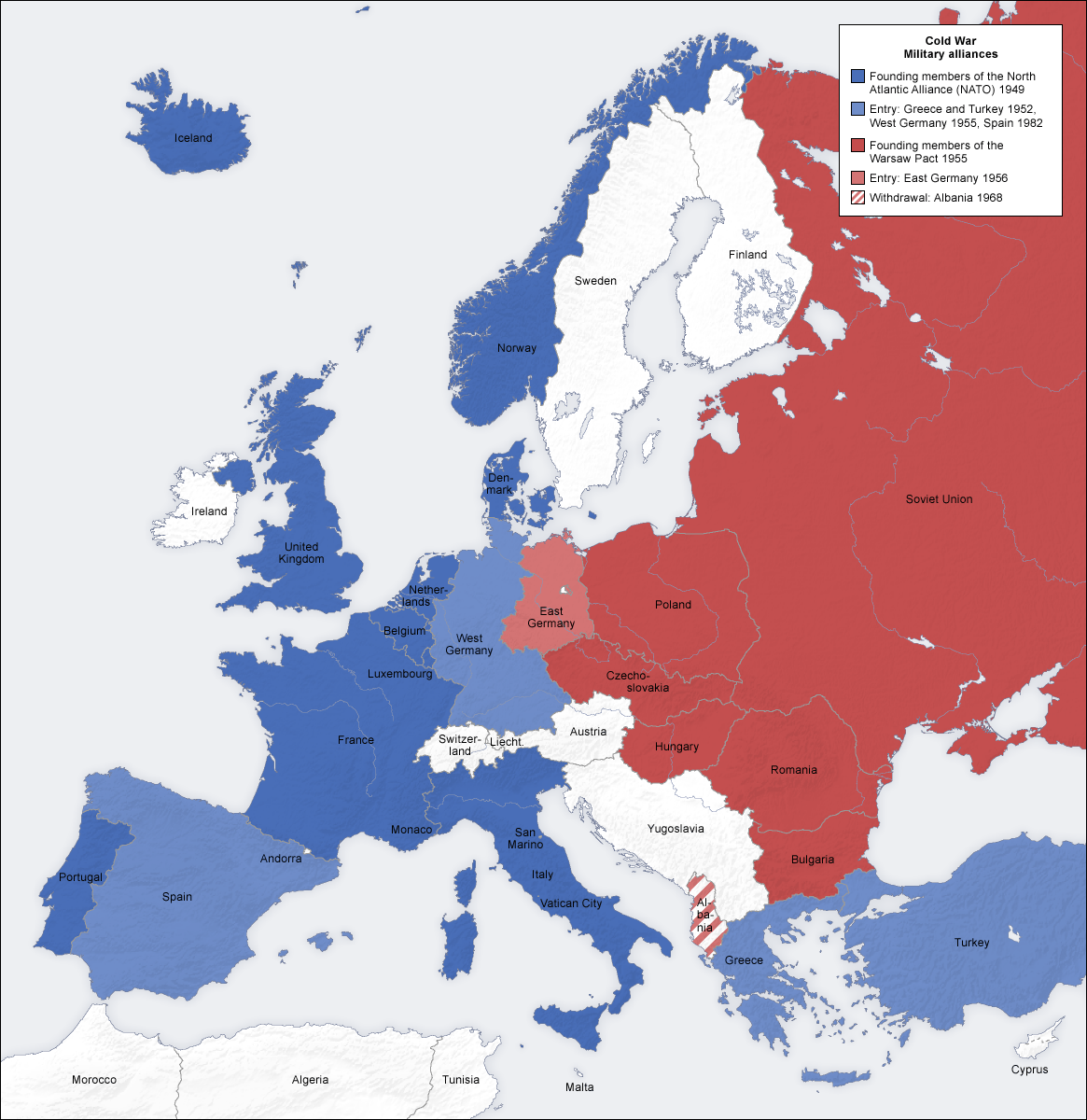

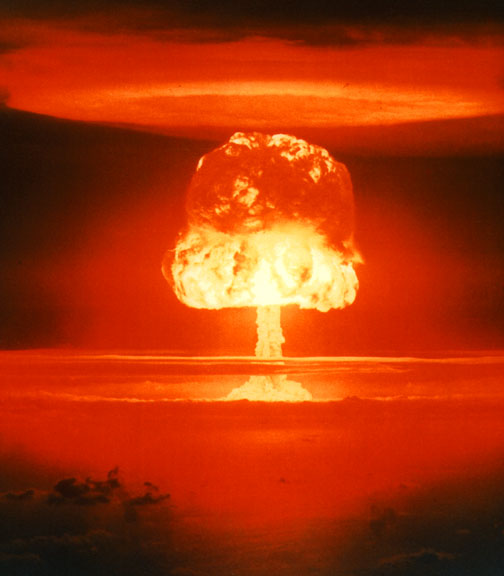

European nations entered new military alliances along East-West lines as well. In April 1949, Great Britain, France, and other Western European Allies united with the U.S. and Canada in a military alliance, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), pledging to defend one another in case of attack. NATO became alarmingly relevant later that summer when the Soviets detonated their first atomic bomb, breaking the U.S. monopoly on nuclear weapons. In the ensuing decades, both superpowers would develop advanced missiles, air forces, and submarines to deliver an overwhelming nuclear attack on the other side’s homeland in case of war. The superpowers adopted a policy of “mutually assured destruction” as a means of preventing a conflict which would almost certainly have destroyed most of the humans and probably much of life on the planet. Britain was next to join the nuclear club in 1952, followed by France in 1960, China in 1964, India in 1974, Pakistan in 1998, and North Korea in 2006. Israel developed weapons in secret in the 1960s, and South Africa developed a couple of weapons in the 1970s but scrapped them and joined the non-proliferation movement by 1991, at the same time the De Klerk government was freeing Nelson Mandela and beginning to end apartheid. Also in 1991 Kazakhstan left the Soviet Union and inherited a nuclear arsenal larger than that of Britain and France, but became the first nation to scrap its nuclear arsenal. We will return to both these events later in the chapter.

European nations entered new military alliances along East-West lines as well. In April 1949, Great Britain, France, and other Western European Allies united with the U.S. and Canada in a military alliance, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), pledging to defend one another in case of attack. NATO became alarmingly relevant later that summer when the Soviets detonated their first atomic bomb, breaking the U.S. monopoly on nuclear weapons. In the ensuing decades, both superpowers would develop advanced missiles, air forces, and submarines to deliver an overwhelming nuclear attack on the other side’s homeland in case of war. The superpowers adopted a policy of “mutually assured destruction” as a means of preventing a conflict which would almost certainly have destroyed most of the humans and probably much of life on the planet. Britain was next to join the nuclear club in 1952, followed by France in 1960, China in 1964, India in 1974, Pakistan in 1998, and North Korea in 2006. Israel developed weapons in secret in the 1960s, and South Africa developed a couple of weapons in the 1970s but scrapped them and joined the non-proliferation movement by 1991, at the same time the De Klerk government was freeing Nelson Mandela and beginning to end apartheid. Also in 1991 Kazakhstan left the Soviet Union and inherited a nuclear arsenal larger than that of Britain and France, but became the first nation to scrap its nuclear arsenal. We will return to both these events later in the chapter.

1949 ended with a new challenge in East Asia, when communist forces led by Mao Zedong defeated the Nationalist armies of Chiang Kai-Shek and established the People’s Republic of China, which we will turn to shortly.

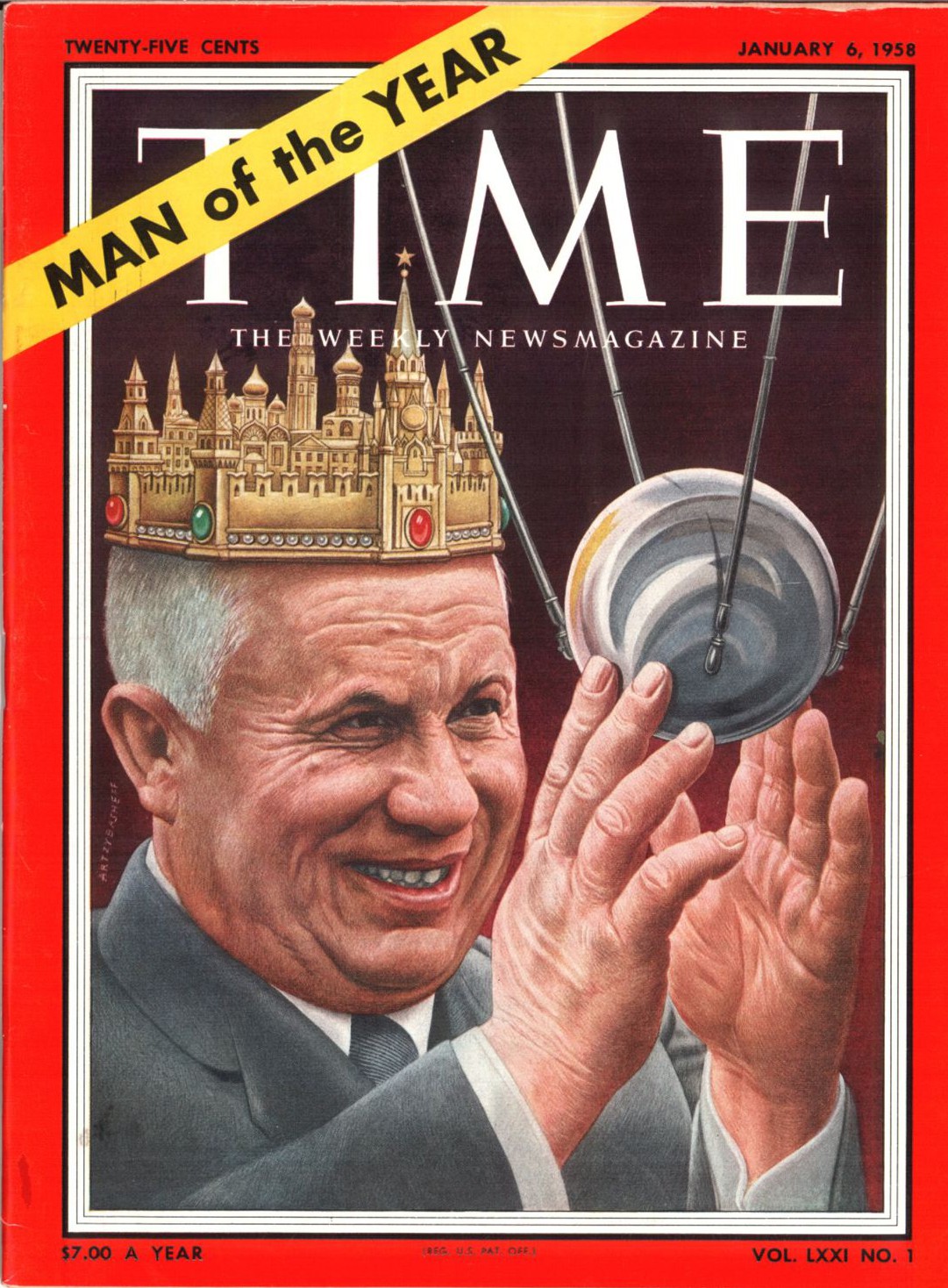

Stalin died in 1953 and after a power struggle in the Politburo a new Premier, Nikita Khrushchev, took power in Moscow. Khrushchev distanced himself from what he called Stalin’s “cult of personality” and revealed the extent of Stalin’s atrocities against perceived political enemies, which had led to the deaths of millions in purges, forced labor, and famine in the previous decades.

Khrushchev announced a new Soviet foreign policy of “peaceful coexistence” with the West, pledging not to extend communism by invading other countries but creating a military alliance, the Warsaw Pact, within the Soviet Bloc in Europe to counterbalance NATO. Khrushchev wanted Soviet communism to provide a higher standard of living for workers. Achieving this was difficult if the military budget was too large, so he sought to lessen tensions with the U.S. and its allies. But there were limits to Khrushchev’s “liberalism”. In 1956, democratic reforms in Hungary led to a possibility of spreading anti-Soviet dissent in neighboring communist countries under Moscow’s control. The Soviets and their Warsaw Pact satellite countries sent troops and tanks to repress any political changes in Hungary and Eastern Europe.

The Cold War in Asia

Although the U.S.S.R. had helped end the Pacific War by invading Manchuria in August 1945, the subsequent reconstruction of Japan was strictly a U.S. affair. By the time the military occupation ended in 1955, Japan had returned to rule by a democratically-elected parliamentary monarchy under the same Emperor, Hirohito. The U.S. guaranteed Japan’s security through a treaty and a military base in Okinawa, and provided financial assistance and preferential access to U.S. markets to rebuild the Japanese economy. This was partly an attempt to counter the perceived communist threat in Asia, and Japan developed a highly successful public-private economic model, ultimately producing electronics and automobiles that would dominate their sectors worldwide.

After World War II, the Nationalists and Communists restarted their civil war, which had been interrupted in 1937 by the Japanese invasion. Mao’s armies were victorious over the corrupt and incompetent Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-Shek. By the end, entire divisions of the Nationalist army were going over to the Communists, and Chiang fled to the island of Taiwan, which had been relinquished to China after being a part of the Japanese Empire for fifty years. There, the Kuomintang continued the Republic of China, which was formally recognized as “China” by the United Nations and the U.S. until the 1970s. Cold War politics was the reason for this diplomatic decision, but even after its end Taiwan’s autonomy from mainland China is still guaranteed by the U.S.

As previously mentioned, war broke out on China’s border a year after the establishment of the People’s Republic. The Korean Peninsula had been divided like Germany at the end of the war with the Soviets administering the north while the south was controlled by the United States. The U.S.S.R. helped establish a communist regime under Kim Il-sung, while the Americans supported an authoritarian “nationalist”, Syngman Rhee. In June 1950, Kim ordered the invasion of the south in an attempt to unite the peninsula. As Kim’s forces quickly took most of the south, the United Nations Security Council ordered a military response, led by the United States. The Soviet Union abstained instead of using its veto power in the Security Council, casting doubt on the western suspicion that Stalin had okayed Kim’s invasion of the south.

By October, U.S.-led United Nations forces had pushed the communist North Korean forces out of the south and had taken the northern capital, Pyongyang. U.N. armies continued to advance northward toward the Chinese border at the Yalu River, which brought China into the war on the North Korean side. On October 25, U.N. troops were surprised by a counterattack by millions of soldiers from China, as Mao defended Chinese territory from foreign invasion and his own new communist government, established only a year before. U.S. commander Douglas MacArthur, a hero of the Pacific War in World War II and leader of the occupation of Japan, talked about his ambition to expand the conflict in Korea to a full-on war with China and contemplated using nuclear weapons. Since the USSR also had nuclear weapons and had signed a mutual-defense treaty with Mao’s new government, a war with China was likely to escalate into World War III. When the general refused to back down and criticized the president’s judgment, Harry Truman fired MacArthur.

After three years of fighting and nearly 3 million Korean deaths (and 54,000 U.S. GIs), the two sides agreed to a cease-fire, but a peace treaty was never concluded and the area has remained a flashpoint. North Korea has become a totalitarian closed society, largely isolated after the fall of the Soviet Union and China’s embrace of capitalism in the 1980s. The Kim family has remained in power despite famine and mismanagement, while defending their regime by developing nuclear weapons. South Korea was ruled by Rhee and the military until a transition to democracy in the 1990s, when it became a successful industrial power following the Japanese development model. The US continues to maintain a military presence in South Korea, and currently there are 28,500 troops stationed near the capital of Seoul. The border between North and South is considered the most heavily militarized zone in the world.

The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 led to continuing diplomatic conflict over the status of Taiwan and war on the Korean Peninsula. An additional hotspot is Tibet, a Himalayan region historically dominated by the Chinese Empire that became an independent nation run by Buddhist monks during the chaotic early years of the Chinese Republic in the 1920s. Mao Zedong decided to reclaim Tibet for his new People’s Republic, and sent in troops in 1951. Tenzin Gyatso, the Dalai Lama from that time is still the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet, and the “Free Tibet” movement is very active around the world.

Internally, Mao’s own totalitarian style had disastrous consequences for the Chinese. The communists had already begun land reform around 1946 in the parts of China they controlled, well before their final victory; the policy had gained them widespread support among the vast peasant population. With the nationalists out of the way, Mao’s policy became more aggressive. He called for the elimination of the landlord class of peasants and redistribution of the land more evenly. Unfortunately, when Mao said elimination, he meant it. Class-motivated mass killings of landlords continued for the next 30 years and estimates of the death tolls range from 14 million to 28 million.

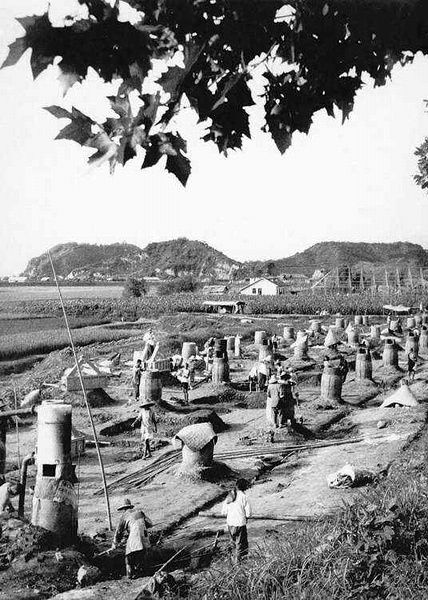

The purge of landlords was followed by the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social plan from 1958 to 1962 that collectivized agriculture and promoted industry. Mao set up 25,000 “people’s communes” of 5,000 families each, which would be responsible for not only feeding themselves and their fellow Chinese citizens, but for providing surpluses to export. Mao insisted on keeping grain exports high in spite of poor harvests. The famine that resulted, known as the Great Chinese Famine, killed 55 million people, although a few million were apparently beaten to death and millions more committed suicide. In some regions of China, people resorted to cannibalism.

This disaster caused some prominent communist party members to question Mao’s leadership, but he maintained support in the army and blamed the famine on a lack of socialist commitment among the Chinese. Mao initiated his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966, leading the military to recruit young people to reinforce Maoist ideology and purge remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society. Schools and universities were closed, and Red Guard troops were encouraged to harass and even murder intellectuals. Educated people were beaten, terrorized, and banished to the countryside to be “reeducated” by the peasants. The death toll of the cultural revolution is debated, but estimates range from 3 to 10 million. It delayed Chinese industrialization and modernization, and a generation of Chinese were deprived of an education.

As seen in the last chapter, efforts by the Vietnamese to liberate themselves from the French after World War II were initially thwarted. This changed in 1954 when Ho Chi Minh’s anti-colonial forces defeated the French in northern Vietnam at the battle of Dien Bien Phu. The French decided to abandon their colony of Indochina, preferring to focus their efforts on maintaining their empire closer to home in Algeria (which we have seen was also unsuccessful). Ignoring the example of the Korean War, the French left Vietnam divided between a communist north and a non-communist south; with the vague promise of an eventual referendum in the south to determine whether or not the country would be reunited.

The vote would never take place. The United States began sending military advisers to South Vietnam almost as soon as the French withdrew. President Dwight Eisenhower, elected in 1952, invoked the “domino theory” to help the unpopular regime in South Vietnam prevent elections which would have made the extremely popular Ho Chi Minh leader of a unified nation. This theory posited that every country the “fell” to communism represented one more step world domination by America’s enemies, although after the “Sino-Soviet Split” of 1956, it was unclear which communist nation was the threat in Vietnam, then Laos, then Cambodia, Burma, India, etc. The U.S. also sent military and economic aid to neighboring Laos, also newly independent from France, in an attempt to prop up a monarchy that was in conflict with Soviet-supported Pathet Lao guerrillas.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s the CIA and U.S. military advisors supported the South Vietnamese government. By the 1960s, the issue of Vietnam would enormously affect domestic politics in the United States, especially after President Lyndon Johnson began sending hundreds of thousands of U.S. soldiers to defend South Vietnam in 1965. In 1969 and 1970, Richard Nixon bombed and invaded Cambodia, but could not defeat the Viet Cong guerillas. The U.S. finally withdrew in 1973, after 58,000 U.S. troops and over a million Vietnamese had been killed. Without U.S. support, the government of the South lost the war and Vietnam was unified in 1975. Ho Chi Minh did not live to see it – he died in 1969 at age 79.

Cold War in the Middle East

In the last chapter, we examined how the establishment of Israel in 1948 immediately led to a series of conflicts with its Arab neighbors. The defeat of Arab forces by Israel in 1949 led to a surge of Arab nationalism, led by Egyptian leader Gamal Abdul Nasser, who became head of state in 1954 after a military coup that ended the Egyptian monarchy. Nasser’s popularity was cemented when he took control of the Suez Canal, surrounded by Egypt but administered by the British and French, in 1956. In this crisis, the U.S. and U.S.S.R. forced Great Britain, France, and Israel to accept Egyptian control of the canal to avoid a larger conflict. Nasser became a hero for the Arab world, standing up to both the old colonial powers and what the Arabs saw as their creation, the new state of Israel.

a failed assassination attempt against him, October 1954.

Nasser’s ruling model became an inspiration for many Arabs. Like Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey in the 1920s, Nasser established a secular state dedicated to improving the lives of ordinary people. He largely separated religion and politics, supported government intervention in the economy to prevent foreign control, and provided more and better social services. Nasser, a former army colonel, also relied on the military as the most reliable and disciplined institution to maintain unity and order. This “Nasserism” became the ideology of the Ba’ath Party, formed in Syria and later in Iraq in the 1950s among military officers.

The Egyptian leader skillfully took advantage of Cold War politics, playing the United States and the Soviet Union against each other in order to gain military and economic aid. The Soviets in particular supported the construction of the massive Aswan Dam, completed in stages by 1970 to control the flooding of the Nile while providing hydroelectric power to Egypt.

Nasser preached pan-Arabism, the goal that all Arabs should be united in one federated nation. Egypt and Syria briefly united under this model in the early 1960s, while after Nasser’s death, Libya, Syria, and Iraq federated for a time in the 1970s. The liberation of Algeria from France in 1962 was a moment of inspiration; another was the unification of Palestinians in the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1964, led by Yasser Arafat and his Fatah Party. Hatred and resentment for Israel was (and remains) a powerful unifying factor in the region. Arab resistance and Cold War considerations led the U.S. to continue its support of Israel, which was supported by Jewish Americans, but also by Christian fundamentalist evangelicals, many of whom consider the reestablishment of the Israel as the beginning of the apocalyptical End Times and the return of the Messiah. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union sought allies in the Middle East, which was much closer to its borders than to America. Russia still maintains its only naval base on the Mediterranean in Syria, dating from the time it began supporting the Ba’athi Assad family in that country in the late 1970s.

Textbooks often describe the Islamic resurgence that began in the 1970s, but usually consider this only as a religious movement. Some critics of Islam claim the Muslim world has never recovered from the First Crusade, when Christian armies captured Jerusalem in 1099 CE and over the course of a few days murdered almost the entire Muslim population of the city. There may be some truth in this statement, but we don’t have to look back several centuries to find reasons why populations that happen to be Muslim resent populations that happen to be Christian. And if globalization, which we will cover in more detail in the next chapter, is primarily an economic development that has overtaken world politics, then resistance to globalization should be considered in economic and political terms.

The places Muslims and Christians most often find themselves in conflict are often where western Europeans and Americans have been very active in extracting natural resources from territories occupied by Muslims. Western oil companies in the Persian Gulf, for example, have had a decisive role in the relationships between the governments of Britain and the US and the people and governments of the region. For example, when the Iranian Prime Minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, decided to nationalize the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP), Winston Churchill convinced Harry S. Truman that Mosaddegh had to go. Britain’s MI-6 and the CIA organized a coup against the elected government of Iran and installed Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi as ruler of Iran in 1953 to insure a steady flow of oil out of Iran.

Oil production in Iran rose quickly from less than a million barrels per day in the 1950s to 6 million barrels daily in the mid-1970s. However, the oil boom of the 1970s widened the gap between the rich and poor in Iran. In 1971, the 2,500th anniversary celebration of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great in the sixth century BCE was attended by jet-setters from around the world while Iranians were excluded and their poverty was ignored. The Shah began a policy of embracing western culture and westernizing Iran; conservative Muslims objected. The new consumer goods and cultural changes were generally available only to the richest Iranians, and were not accompanied by political liberalization. The Shah’s secret police force, SAVAK, terrorized the population and routinely assassinated the Shah’s critics. In 1977, SAVAK killed several Islamic leaders including Mostafa Khomeini, son of the ayatollah.

The outbreak of the Iranian Revolution caught the Shah by surprise. When the Muslim clergy announced an open-air prayer meeting on the annual holiday marking the end of Ramadan, the Shah panicked and declared martial law. 5,000 protesters took to the streets of Tehran. The army fired into the crowd, killing 64 people. The ayatollah Khomeini claimed 4,000 people had been killed and workers at Tehran’s oil refineries and government workers declared a general strike that brought the economy to a standstill. By early December, more than 10% of the Iranian people were marching in anti-Shah demonstrations. The U.S. Government was hated for helping to install the Shah, and also for statements by President Jimmy Carter supporting the Iranian Government and the “special relationship” the Shah had with the U.S. The ailing Shah abandoned Iran, eventually arriving for treatment in the United States, while Khomeini proclaimed a new Islamic Republic.

A group of Islamist students stormed the American Embassy in Tehran in November 1979 and took the staff as hostages. 52 Americans were held for 444 days, until the inauguration of Ronald Reagan in January 1981. The ayatollah, who was an astute politician as well as a religious leader, supported keeping the hostages on purely political grounds. He told reporters, “This action has many benefits…This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people’s vote without difficulty.”

However, the new Iranian regime also confronted resistance from the Arab world, especially from Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein. Not only were the Iranians Persian, rather than Arab, most were also followers of Shia Islam, rather than the more common Sunni branch which is prevalent in the Arab world and among all Muslims. Although Shi’ites and Sunnis had lived in peace for centuries, Iran’s new clerical state was deemed a threat by its Arab neighbors, especially by the conservative Sunni regime in Saudi Arabia.

Iraq, however, had its own particularities: not only were the specifically Shia holy sites located in Saddam Hussein’s country, but a majority of the Iraqis were Shi’ite Arabs as well. Hussein, meanwhile, was a Ba’athist, promoting Arab nationalism in a secular state ruled by his military. In September 1980 he sent his armies into Iran in an attempt to take advantage of what they supposed would be political chaos. Hussein claimed that he was protecting Arabs living in the Iranian border region, although conveniently, these areas also had vast oil deposits. The Iran-Iraq War lasted 8 years and, like the hostage crisis, helped consolidate the power of the Khomeini regime. The US, USSR, France, and many Arab countries provided support for Iraq, which used chemical weapons against Iranian military and civilian targets. The death toll has been estimated as 800,000 Iranians and up to 500,000 Iraqis.

Hussein had gained nothing in the war but debt and demands for autonomy by non-Arab ethnic Kurds in northern Iraq; he responded with chemical attacks on civilian Kurdish populations. In 1990, the Iraqi dictator then decided to incorporate Kuwait into his nation, claiming that it had historically been part of Mesopotamia (which was plausible, given the absurd way the British had drawn national boundaries after World War I). The United Nations, led by the U.S. pushed Hussein out of Kuwait. Not even the Saudis wanted the Iraqi dictator to take the tiny kingdom, which despite its size had as much oil as Iraq. However, although it decimated Hussein’s retreating army on the infamous “Highway of Death”, the coalition stopped short of toppling Hussein himself, which would have consequences over the next two decades.

Latin America and the Cold War

The twentieth century began in Latin America with the Mexican Revolution, when Pancho Villa in northern Mexico and Emiliano Zapata in southern Mexico created an opportunity for new liberal forces led by Alvaro Obregon. After defeating Villa on the battlefield, Obregon held a constitutional convention in 1917 which produced a document that embraced agrarian reform, an eight-hour work day and the right to organize labor unions; and a declaration that the subsoil belongs to the state in the name of the people. The was a return to the tradition of the Spanish Empire that subsurface minerals belonged to the people or to the state, rather than to individuals or companies. These ideas were inspirational for the rest of Latin America and even other parts of the world: the Mexican Revolution predated the Bolshevik Revolution by several months.

It took a generation for Mexico to realize this goal, but in the 1930s, under President Lázaro Cárdenas, land reform was implemented that brought back indigenous communal landholdings, broken up during the Diaz period. And in 1938, Cárdenas nationalized Mexican oil, taking over leases given to U.S. and British oil companies. The American president, Franklin Roosevelt, who had begun a “Good Neighbor Policy” toward Latin America when he took office, to emphasize trade and cooperation rather than military force, did not intervene when oil companies objected. Britain acquiesced in order to assure Mexican support in what everyone understood would soon be the next world war.

Cárdenas was part of a wave of populist heads of state in Latin America, charismatic leaders who tried to address the needs of “the people,” which by the 1930s and 1940s included rural peasants as well as the urban working class. Latin American Populism also attracted a rising professional middle class, shut out of political power by traditional oligarchies. In Argentina, this new middle class included first-generation immigrants from Europe who supported a new Radical Party in the first decades of the twentieth century. Argentina was second only to the United States as an immigration choice for impoverished Europeans, particularly Italians, Germans, and Eastern European Jews. In other cases, army officers who had received professional training either at home or abroad by European military missions felt that the oligarchs were insufficiently patriotic and needed to be replaced.

The populists also supported nationalist economic measures, including policies of import substitution industrialization, land reform, and efforts to reduce dependency on international markets for their mining or agricultural goods. The crisis of the Great Depression emphasized the importance of building independent domestic economies and instituting education, housing, and infrastructure improvements for all of the people. The global war against fascism inspired many to embrace democracy and overthrow long-standing military regimes, like in Guatemala, Venezuela, and Cuba; although these attempts at democratic practices were frequently short-lived.

Two of the most notable populist leaders are also examples of civilian and military versions of populism: Getúlio Vargas of Brazil and Juan Perón of Argentina. Vargas was an opposition candidate who lost in a fraudulent election to an oligarchy-backed candidate in 1930; a brief uprising made him president. He skillfully faced down a separatist revolt in the wealthy coffee state of Sao Paulo, but after embracing a degree of liberal democracy, in 1937 Vargas established an authoritarian state in order to prevent communist-supported leftists being elected. However, he also rooted out a new fascist movement and disbanded it as well, setting himself up to accept U.S. aid and support the Allies in World War II. Brazil was the only nation in Latin America to send troops to fight alongside the Allies in Europe. Vargas stepped down in 1945, but ran again for president in 1950 and was reelected.

Perón, on the other hand, was an army officer who had served as a military attache in Italy in the 1930s, witnessing up close the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini. Argentina at the time was governed by politicians elected through fraud that suppressed calls for reform by the Radical Party. In 1943, in the midst of World War II, the military overthrew the corrupt regime, instituting a government that they felt was more dignified and responded more directly to the people. Juan Perón, a key player in the coup, chose to become the Minister of Labor. By guaranteeing labor law and favoring the workers in negotiations, he became popular among the urban masses in Buenos Aires. Although the military regime grew nervous about his growing popularity and had Perón arrested, the workers came to his aid. He was released and was elected president of Argentina in 1946.

Perón benefited from a postwar economic boom in Argentina. He could promise and deliver on higher wages, better living and working conditions, and vacations for workers as tax revenues rolled in because of high international prices for Argentine wheat and beef. In the context of the Cold War, Perón proclaimed that he represented a “third way” between unfettered capitalism and totalitarian communism. Perón claimed that his government improved the lives of Argentinians without having to take sides in the superpower conflict. This made him particularly annoying to the United States, which often had to face Argentine opposition at regional conferences.

Perón bet on never-ending good times, especially when it seemed that the Korean War might lead to a World War III in which Argentina would benefit. However, shortly after he was reelected in 1952, Perón’s popular wife, Eva Duarte, died of ovarian cancer at age 33. Hundreds of thousands attended her funeral and a cult of “Santa Evita” quickly took hold. The Argentine economy began to suffer as the world recovered from World War II and Argentina faced competition for its wheat and beef in the international market. Like Vargas, Perón also faced inflation and political scandals. A bitter fight with the Catholic Church led to Perón’s ouster by the military in 1955 and the suppression of the Peronist movement until Peron was invited back from exile to be reelected president in 1973.

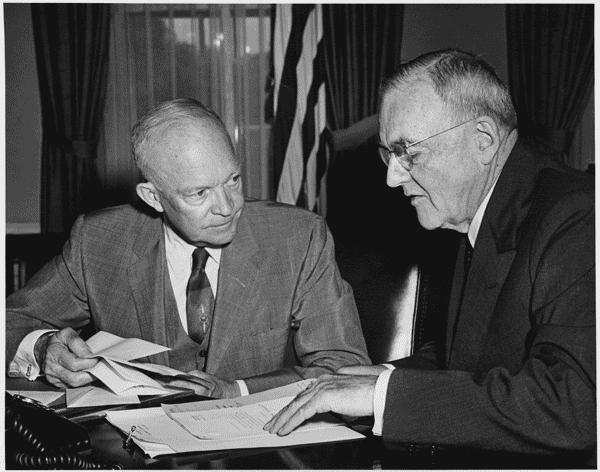

Although the United States congratulated itself that it had replaced blatant military intervention and “dollar diplomacy” with a “Good Neighbor Policy” under Franklin Roosevelt, nations like Costa Rica, Guatemala and Honduras were still thoroughly dominated by the United Fruit Company (UFC); still Banana Republics. After World War II, the Dulles brothers became leaders in developing U.S. foreign policy in Latin America. John Foster Dulles was a corporate lawyer who had helped negotiate huge land giveaways to UFC by the governments of Guatemala and Honduras. After serving as a Senator from New York, Dulles was appointed secretary of State by Dwight Eisenhower in 1953. His brother Allen Dulles was on UFC’s board of directors before he served as President Eisenhower’s CIA Director.

In 1954 the democratically-elected government of Guatemala began talking about seizing some of the vast tracts of land the United Fruit Company had acquired but was not using. The government planned to buy back the land from UFC and redistribute it to the poor. The Dulles brothers accused the Guatemalan government of having close ties with the Soviets and sent in the CIA to overthrow it in a military coup. Guatemalans resisted the new regime and the country fell into a civil war that lasted from 1960 to 1996 and killed up to 200,000 people.

One of the key elements of Latin America’s relationship with the outside world seems to be the question of revolution and the threat nations like the U.S. claimed to fear, of socialist, anti-capitalist movements in the Western Hemisphere. In many cases the anti-capitalism expressed by Latin Americans was actually resistance to what they perceived as economic imperialism by nations like the U.S., which regularly defended American-based corporations that operated freely in their nations and often intervened in their politics. Latin American nationalist leaders like Getúlio Vargas in Brazil (President from 1930-45 and 1951-54), Juan Perón in Argentina (President from 1946-55 and 1973-4), or Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico (President from 1934-40), who nationalized the Mexican oil industry, were not Marxists, or even particularly socialist in their orientation or policies. Import Substitution Industrialization was a capitalist approach to reducing dependency, and even when nations like Mexico nationalized natural resource extraction, they usually compensated foreign companies for the assets they were expropriating and then they ran the extractive industries as businesses in the world economy. Even when the government’s goal was something like land reform, they usually tried to compensate the former owners. The conflict over land reform in Guatemala was misrepresented by the Dulles brothers. The Guatemalan government offered UFC a price for the lands it took back based on the values claimed in the corporation’s tax filings. It may have been an open secret that UFC was defrauding the Guatemalan government, but the government was well within its rights to call that bluff. A truly communist government determined to eliminate capitalism in Guatemala might simply have claimed UFC had acquired the lands illegally and taken them with no offer of compensation.

Many idealists in Latin America and elsewhere were radicalized by the violence nations such as the United States approved or initiated to protect the interests of corporations but justified as defenses of democracy. An example of this was the experience Ernesto “Che” Guevara, who witnessed the Bolivian Revolution of 1952 before moving on to Guatemala in 1954. Bolivia’s struggle began when the candidate of the Movimiento Nationalista Revolucionario(MNR) won the presidential election of 1951 but was prevented by the military from taking office. Victor Paz Estenssoro armed civilians and the MNR took power after 3 days and 600 casualties. He served his first term from 1952 to 1956, and accepted US financial aid in return for compensating the tin mines he nationalized. Estenssoro softened the revolution’s approach to rewriting the mineral and petroleum laws, but he did redistribute land. Bolivians approved of his leadership and Estenssoro was re-elected in 1960, 1964, and 1985.

Peasants on the altiplano, the high Andean plateau around the city of Cochabamba, seeing the changes in the mining codes, began seizing haciendas and dividing the land up amongst themselves. The government passed an Agrarian Reform Decree in 1953 to capture the campesinos’ support and control the process a bit. Before the revolution, less than 1% of the richest landowners in Bolivia owned half of the country’s land and 6% owned 92% of Bolivia. Under the reform, 185,000 peasant families, about half of all rural families, got titles to an average of about 20 hectares each. National agricultural output fell by about 10% after the land distribution, but probably because people were growing and keeping more produce for home use and trading it informally rather than taking it to commercial or export markets. Some cities saw food shortages, but these were offset by imports and some foreign aid.

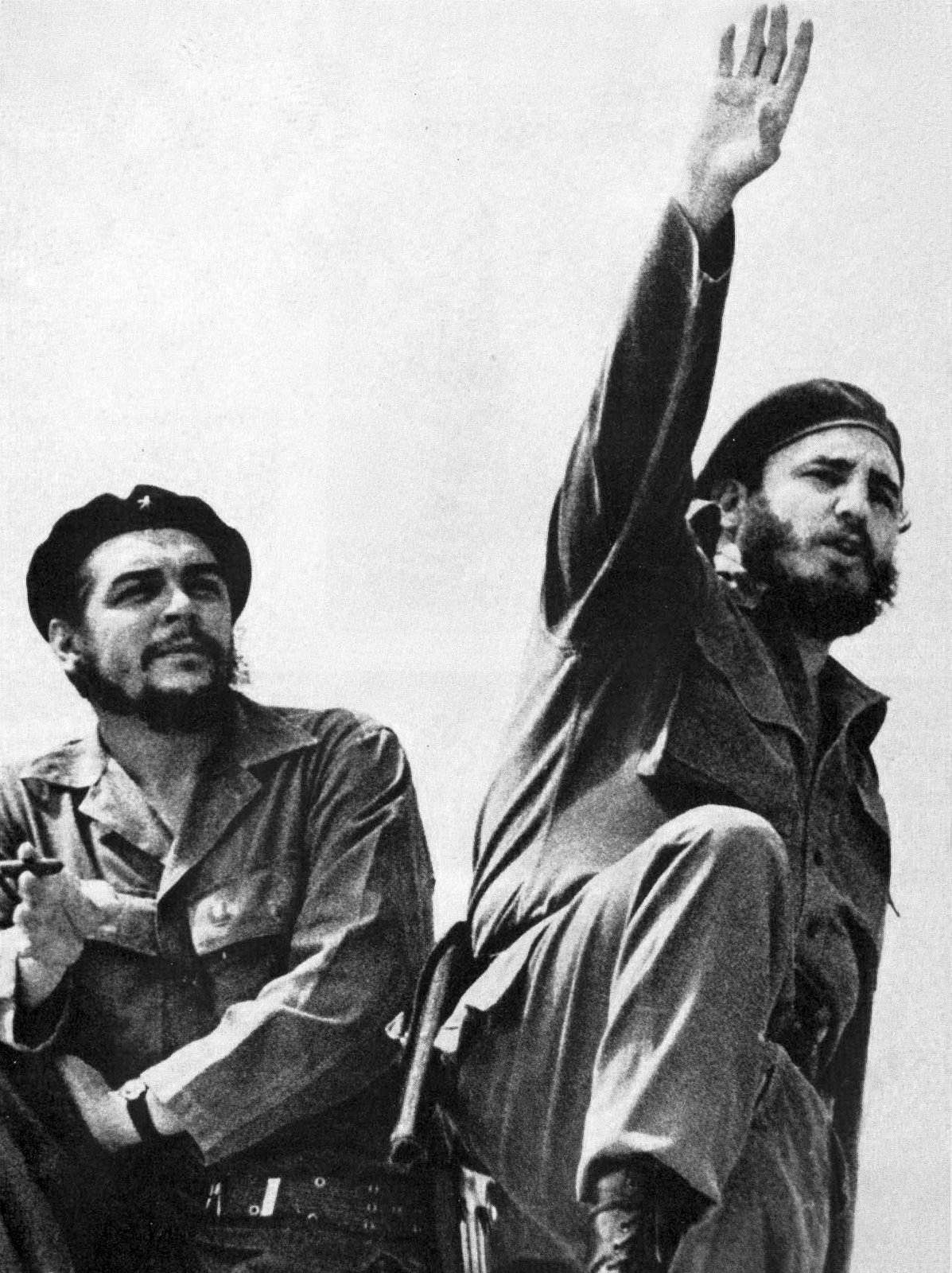

After witnessing this revolutionary change in Bolivia, Guevara went to Guatemala and watched a similar attempt crushed by imperialist armies operating to protect corporate profits. This experience and his romance with a Peruvian Marxist economist named Hilda Gadea Acosta, who he married in 1955, radicalized Che. When he was placed on an enemies list by the new Guatemalan regime, Guevara escaped to Mexico where he met Raúl and Fidel Castro, who were in exile there following a failed revolutionary coup in Cuba. Guevara became an ally of the Castros in June 1955 and joined the revolution. About 80 revolutionaries arrived in late November 1956 on the eastern tip of Cuba, but their numbers were reduced to about 20 in their first skirmish with Fulgencio Battista’s army. The survivors fled into the Sierra Maestra mountains and enlisted peasants into a guerilla army that harried the Cuban army for the next two years. In 1958, Guevara explained the guerillas’ success:

“The enemy soldier in the Cuban example which at present concerns us, is the junior partner of the dictator; he is the man who gets the last crumb left by a long line of profiteers that begins in Wall Street and ends with him. He is disposed to defend his privileges, but he is disposed to defend them only to the degree that they are important to him. His salary and his pension are worth some suffering and some dangers, but they are never worth his life. If the price of maintaining them will cost it, he is better off giving them up; that is to say, withdrawing from the face of the guerrilla danger.”

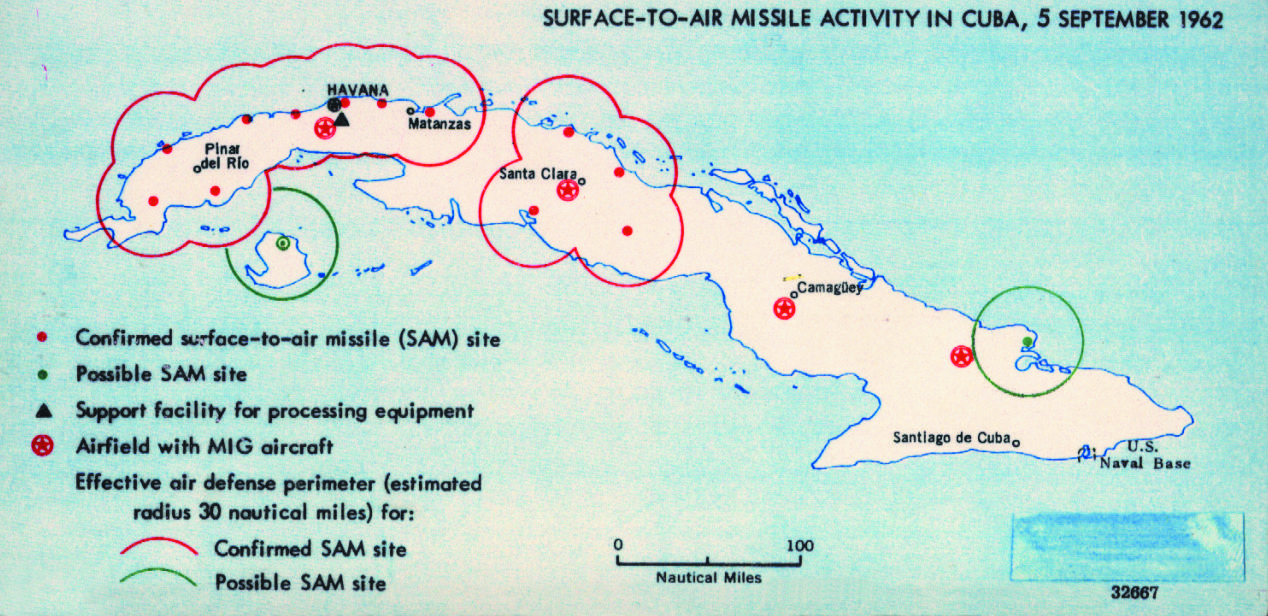

The cold war was played out mostly through proxy wars: regional conflicts like the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Russia-Afghanistan War where the combatants were provisioned, supported, and sometimes joined by troops from the superpowers. Occasionally, the heat level increased and the U.S. and U.S.S.R. barely avoided direct conflict. One of those times was during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The U.S.S.R. became a trading partner of Cuba after Marxist revolutionaries Fidel and Raul Castro and Che Guevara overthrew the American-backed Battista government in 1959 and replaced it with a revolutionary socialist state. President Kennedy supported a CIA-sponsored plan to invade Cuba using anti-Castro Cubans in 1961, but the Bay of Pigs invasion was a fiasco. In October 1962 the U.S. discovered that the U.S.S.R. had deployed nuclear missiles in Cuba, less than 100 miles from the continental U.S. Castro had not initially been looking for a close alliance with the Soviets, but he seems to have believed that the U.S. was going to continue its attacks (recently declassified CIA documents describing several more coup and assassination plans proved Castro’s fears were well-founded).

The 13-day standoff ended with the Soviet Union withdrawing its missiles in return for American promises not to try again to overthrow Castro. Che Guevara announced “Our revolution is endangering all American possessions in Latin America. We are telling these countries to make their own revolution.” Che headed the Cuban delegation to the United Nations in 1964, where he made a speech criticizing apartheid in South Africa and said of the U.S., “Those who kill their own children and discriminate daily against them because of the color of their skin; those who let the murderers of blacks remain free, protecting them, and furthermore punishing the black population because they demand their legitimate rights as free men—how can those who do this consider themselves guardians of freedom?” Guevara increasingly believed that the global north (the northern hemisphere nations) was guilty of oppressing the global south. He even criticized the U.S.S.R. for not doing enough to end imperialism, accusing Russia of forgetting Marx. Che supported the independence movements of indigenous peoples and left Cuba to try to encourage these revolutions, first in the Congo and then in Bolivia, where he was captured by CIA-assisted Bolivian government forces in 1967 and summarily executed. Fidel Castro continued as Cuban president until 2008 when his brother Raul became President. Fidel died in 2016 and Raul handed over the Presidency in 2018, although he remains the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba until a planned retirement in 2021.

Twentieth-century cold-war conflicts involving Oil have not been limited to the Persian Gulf. Development of Venezuela’s oil resources, thought to be at least a fifth of known global reserves, began in the 1910s when the country’s president granted concessions to his friends to explore, drill, and refine oil. These concessions were quickly sold to foreign oil companies. In 1941 a reform government gained power and passed the Hydrocarbons Law of 1943 under which the government would receive 50% of the profits of the oil industry. The outbreak of World War II had increased demand for oil, and the Venezuelan government granted a series of new concessions that were snapped up in spite of the 50% tax. The postwar explosion of automobile ownership in the U.S. continued to drive demand, and Venezuelan production increased. Venezuela bought the Cities Service company and CITGO gas became a key export of Venezuela. In 1976, the government nationalized the oil industry. Oil was a mixed blessing for Venezuela, providing high levels of revenue to support government programs benefitting the people; but also preventing Venezuelan industry from diversifying. However, the CITGO sign became a welcome sight for many New Englanders, as the company has donated millions of gallons of home heating oil to help hundreds of thousands of families in the Northeastern United States over several decades.

During the 1950s and 1960s colonialism mostly ended in Africa, although not without occasional atrocities such as the British oppression of the Kikuyu in Kenya in a conflict the British still lost, despite having overwhelming force on their side. In South Africa, the white government of F. W. De Klerk, who became president in 1989, finally began to dismantle the apartheid system that had oppressed the black majority for generations. Nelson Mandela (1918-2013) was a member of a royal native family of the Xhosa people who became a lawyer in Johannesburg and became active in politics after the white government began instituting apartheid policies in the 1940s. Apartheid was a system of racial segregation that completely separated the black majority from the white rulers and deprived them of political and civil rights. Mandela became president of the African National Congress (ANC), an organization established in 1912 to defend the rights of native Africans and mixed-race people in South Africa. He was arrested in 1956 for sedition and treason. Despite a commitment to non-violence, Mandela began leading acts of sabotage against government properties in 1961 and was convicted in 1962 and sentenced to life in prison.

De Klerk visited Nelson Mandela in prison a few months after becoming President and spoke with him for 3 hours. In 1990, De Klerk called for a new Constitution and shut down South Africa’s nuclear weapons program. Then he freed Mandela after 27 years as a political prisoner and lifted the ban on the ANC operating as a political party. After losing the presidential election to him in 1994, De Klerk served as one of Mandela’s Deputy Presidents from 1994-6. Mandela served as president for a single term and then stepped down. He focused on reconciliation while in office and in his retirement devoted himself to combatting poverty and AIDS.

Cold War in the US

Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy burst onto the American political scene during a speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, in February 1950. Waving a sheet of paper in the air, McCarthy falsely announced that he was holding a list of 205 names “that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping [U.S.] policy.” Since McCarthy had no actual list, the number quickly changed to fifty-seven, then eighty-one. Finally, he promised to disclose the name of just one communist, the nation’s “top Soviet agent.” The shifting numbers brought ridicule, but it didn’t matter: McCarthy’s lies won him fame and fueled a new “red scare.”

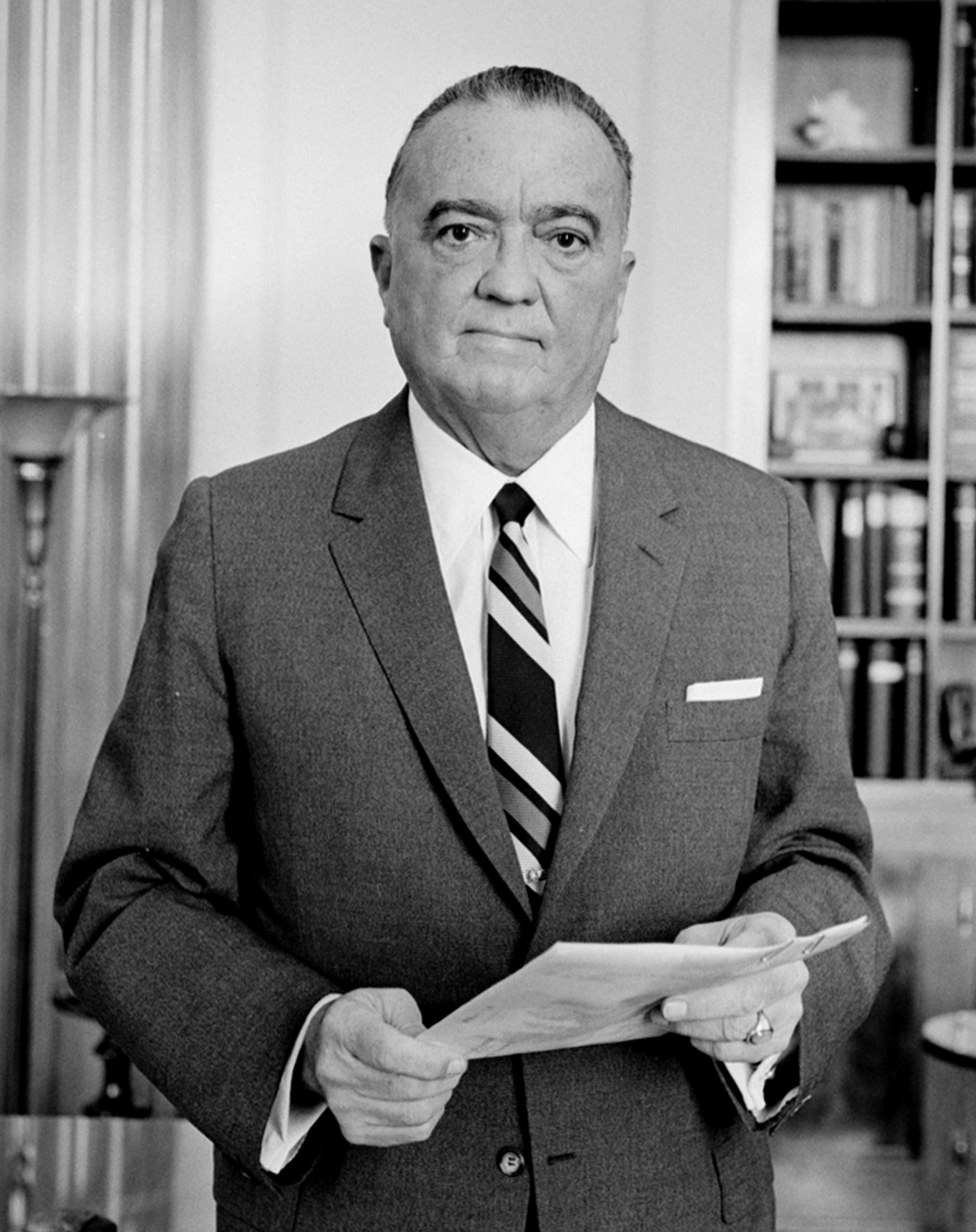

McCarthyism was part of a widespread anticommunist propaganda campaign directed at Cold War America by the U.S. government. Only two years after World War II, President Truman issued Executive Order 9835, establishing loyalty reviews for federal employees. The FBI conducted close examinations of all potential “security risks” among Foreign Service officers. When the Korean War began, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover unsuccessfully petitioned Truman to suspend habeus corpus and detain 12,000 Americans suspected of disloyalty. Hoover grew increasingly frustrated with what he saw as the President’s and Supreme Court’s obstruction of his ability to prosecute people for their political opinions. In 1956, Hoover began a counterintelligence program, COINTELPRO, to disrupt the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA). The scope of Hoover’s suspicions and COINTELPRO’s targets grew to include civil rights groups, feminists, environmentalists, Native American activists, and anti-war protestors before the program’s dissolution in 1971. The program’s domestic espionage and psychological warfare tactics were widely criticized. Many believed the FBI had greatly overstepped its authority; some even accused COINTELPRO of planning the assassinations of some of the program’s targets.

In Congress, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations held over a hundred investigations and hearings on communist influence in American society between 1949 and 1954. The Internal Security Act, passed by Congress in September 1950, required all “communist organizations” to register with the government, gave the government greater powers to investigate sedition, and made it possible to prevent suspected individuals from gaining or keeping their citizenship. In the first year, the new law turned away over 50,000 immigrants from Germany and over 10,000 displaced Russians. There were, of course, American communists in the United States. The CPUSA enjoyed most of its influence as labor organizers and as strong opponents of Jim Crow segregation. But even at the height of the Depression, communism never attracted many American. McCarthy’s and Hoover’s witch-hunts hurled accusations and ruined careers less on people’s communist sentiments and more on their opposition to civil rights and anti-war protestors.

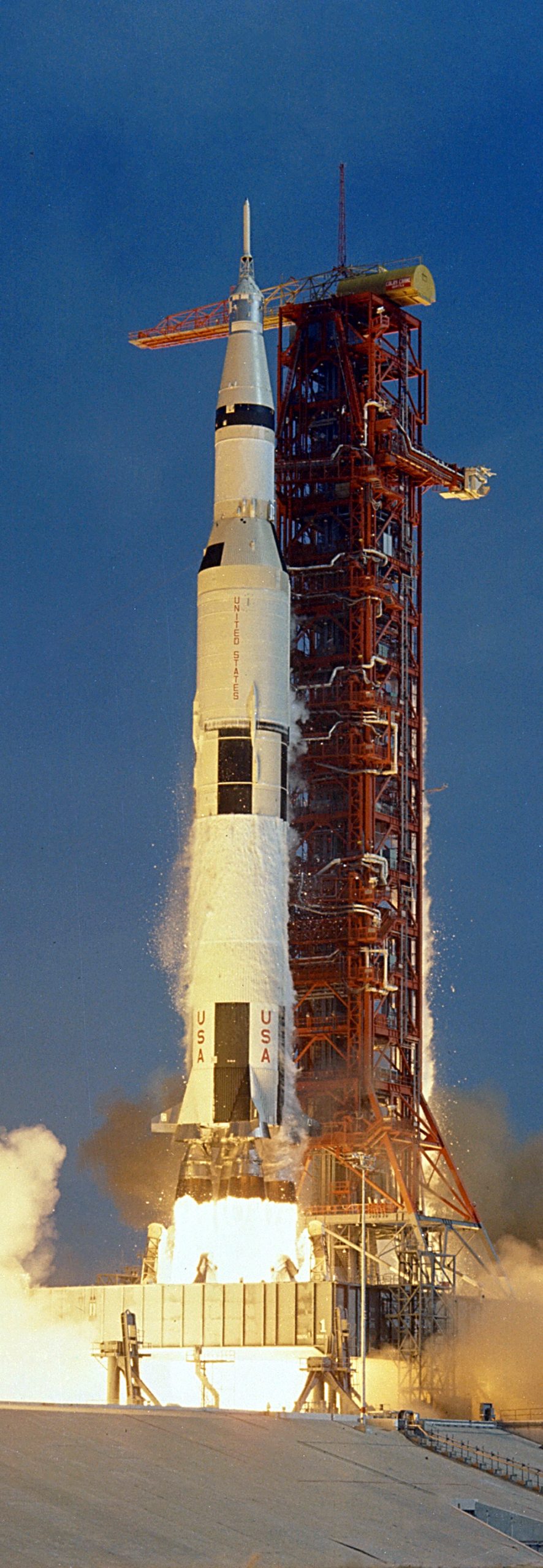

The arms race was not only about nuclear technology, but also a contest to improve the distance and accuracy of missiles which could carry a nuclear load. The missile race indirectly led to the space race, as both the U.S. and the Soviets initiated programs for space exploration. As Germany collapsed at the close of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union had raced toward Berlin, hoping not only to be first to occupy the capital but to acquire elements of the Nazi V-2 missile program and jet propulsion project. In the last months of the war, the Nazis had developed a “vengeance weapon” to terrorize England, even though Germany had no hope of winning. The V-2 was the world’s first guided ballistic missile, capable of carrying an explosive payload up to six hundred miles. Both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. hoped to capture scientists, designs, and manufacturing equipment to build their own rockets. Germany’s top rocket scientist, Wernher von Braun, surrendered to U.S. troops and eventually became the leader of the American space program. About 1,600 German scientists and engineers found their way into the American program. The Soviet Union’s program was managed by Red Army colonel Sergei Korolev, although the Soviet program also had about 2,000 Germans. Both engineering teams worked to adapt German rocket technology to create an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) that could carry the new nuclear weapons.

Jet technology developed even more rapidly. By the time of the Korean War, jet fighters supported both sides, using identical German technology acquired after World War Two. Commercial jetliners were introduced in the 1950s, replacing ocean liners by the 1970s as passenger transport.

The Soviets achieved success in the missile race first. They even used the ICBM launch vehicle in October 1957, to send Sputnik, the world’s first human-made satellite, into orbit. It was a decisive technological victory, and the Soviet propaganda ministry took full advantage of the opportunity to begin a space race while at the same time warning the U.S. that it could deliver nuclear weapons to American targets.

In response, the U.S. government rushed to perfect its own ICBM technology and in 1958 established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to launch satellites and astronauts into space. Initial American attempts to launch a satellite into orbit suffered spectacular failures, heightening fears of Soviet domination in space. While the American space program struggled, the Soviet Union’s Luna 2 capsule became the first human-made object to touch the moon in September 1959. Then the U.S.S.R. successfully launched a pair of dogs (Belka and Strelka) into orbit and returned them to Earth alive in August 1960 while the American Mercury program languished behind schedule (the first dog the Soviets sent to orbit, Laika, died during the trip). Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was launched into orbit on April 12, 1961. American astronaut Alan Shepard accomplished a suborbital flight in the Freedom 7 capsule on May 5. The United States had been embarrassed, and John Kennedy used America’s frustration over early losses in the “space race” to bolster funding for a manned moon landing, which succeeded on July 20, 1969.

The Cold War ended with the 80s. Between 1989 and 1991, the Soviet system collapsed and Russia lost control of its Eastern European satellites. Soviet leaders Yuri Andropov and Mikhail Gorbachev began relaxing the strict controls the state had been exercising on satellite states. Andropov prevented the U.S.S.R. from invading Poland in 1981 to crush the Solidarity movement, as they had done during the Prague Spring in 1968. By 1989, Solidarity was included in multiparty elections in Poland and the movement’s leader, Lech Walesa, was elected President (1990-95). Andropov’s successor, Gorbachev began a process of perestroika, restructuring the economy, in 1986 and introduced glasnost, a policy of increased openness in politics and support for individual rights including freedom of speech. The freedom of speech Gorbachev granted included freedom to criticize the government, which he would be unable to control.

In October 1989, East Germany’s longtime leader resigned. Erich Honecker had been instrumental in building the Berlin Wall in 1961. Honecker had then ruled the communist nation from 1971 until 1989, and had ordered East German troops to fire on people trying to escape to West Berlin. Over a thousand people were killed over the years. The wall only lasted three weeks after Honecker’s removal from office. He fled first to Russia and then to Chile to evade prosecution over giving the order to fire on people fleeing from East Germany, but by this time he was suffering from advanced liver cancer. Germany didn’t fight too hard to extradite Honecker and he died in 1994 in Santiago.

Honecker had honestly believed the Berlin Wall was unavoidable and that by building it he had prevented a “third world war with millions dead.” Tearing down the wall and reunifying Germany in 1990 were milestones in the end of the Cold War. In 1991, Gorbachev agreed to allow the Baltic Republics (Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia) to secede from the U.S.S.R., and hard-liners in the Kremlin tried to overthrow him in a coup. The president of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin, supported Gorbachev and thwarted the coup. Although Gorbachev had been returned to the Kremlin, Yeltsin began gaining power for himself and Russia at the expense of the Gorbachev and the U.S.S.R. In late 1991, Yeltsin flew the Russian flag over the Kremlin alongside the Soviet flag. On December 25, 1991, Gorbachev resigned as President of the USSR in a televised speech, and handed over the Soviet nuclear codes to Yeltsin. The following day, the U.S.S.R. was dissolved and Yeltsin moved into Gorbachev’s office at the Kremlin.

The collapse of the Soviet Union left the US as the world’s only superpower. This was not welcome news to some of the officials of the old U.S.S.R. We’ll look at how these people consolidated their power in the new Russia when we discuss Globalization in the next chapter.

Media Attributions

- Cold_war_europe_military_alliances_map_en

- 2880px-Map-Germany-1945.svg

- 2880px-Iron_Curtain_map.svg

- Krefeld, Hungerwinter, Demonstration

- 2880px-Flag_of_NATO.svg

- Operation_Castle_-_Romeo_001

- Nikita-Khrushchev-TIME-1958

- Macarthur_hirohito

- 2880px-KoreanWar_recover_Seoul

- Korean_war_1950-1953

- Backyard_furnace4

- Vietcongsuspect

- Nasser_and_RCC_members_welcomed_by_Alexandria,_1954

- Nasser_brokering_ceasefire_with_Chairman_Arafat_and_King_Hussein

- lossy-page1-2880px-President_Truman_and_Prime_Minister_Mohammad_Mossadegh_of_Iran.TIF

- 2880px-Enghlab_Iran

- Iran_hostage_crisis_-_Iraninan_students_comes_up_U.S._embassy_in_Tehran

- Chemical_weapon1

- Vargas_e_Roosevelt

- President_Eisenhower_and_John_Foster_Dulles_in_1956

- CheOnRaft1952

- CheyFidel

- 1962_Cuba_Missiles_(30848755396)

- Operemm-2

- Frederik_de_Klerk_with_Nelson_Mandela_-_World_Economic_Forum_Annual_Meeting_Davos_1992

- Hoover-JEdgar-LOC

- F-86-4fiw

- File written by Adobe Photoshop? 5.2

- West_and_East_Germans_at_the_Brandenburg_Gate_in_1989