1 Modern World History Begins in Asia

Civilization began in India about 4,600 years ago and China’s recorded history began about 2000 BCE. Based on irrigated rice agriculture, the population of China grew to 50 to 60 million people as early as 2,000 years ago. This population was originally divided into several small kingdoms whose ruling families were connected through political marriages. Beginning in 221 BCE, the Chinese created an empire that lasted over two thousand years under a series of more than a dozen dynasties. The early imperial governments began construction of the called Long Walls, and dug the Grand Canal to connect the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in the sixth century CE. China held a monopoly on the creation of silk, which was a closely-held state secret for millennia, and led the world in iron, copper, and porcelain production as well as a variety of technological inventions including the compass, gunpowder, paper-making, mechanical clocks, and moveable type printing.

The social stability that allowed Chinese culture to produce these innovations was based on not only the imperial form of government, but on an elaborate system of professional civil service. The early establishment of a professional administrative class of “scholar-officials” was a remarkable element of imperial Chinese rule that made it more stable, longer-lasting, and at least potentially less oppressive than empires in other parts of the world. The imperial courts sent thousands of highly-educated administrators throughout the empire and China was ruled not by hereditary nobles or even elected representatives, but by a class of men who had received rigorous training and had passed very stringent examinations to prove themselves qualified to lead.

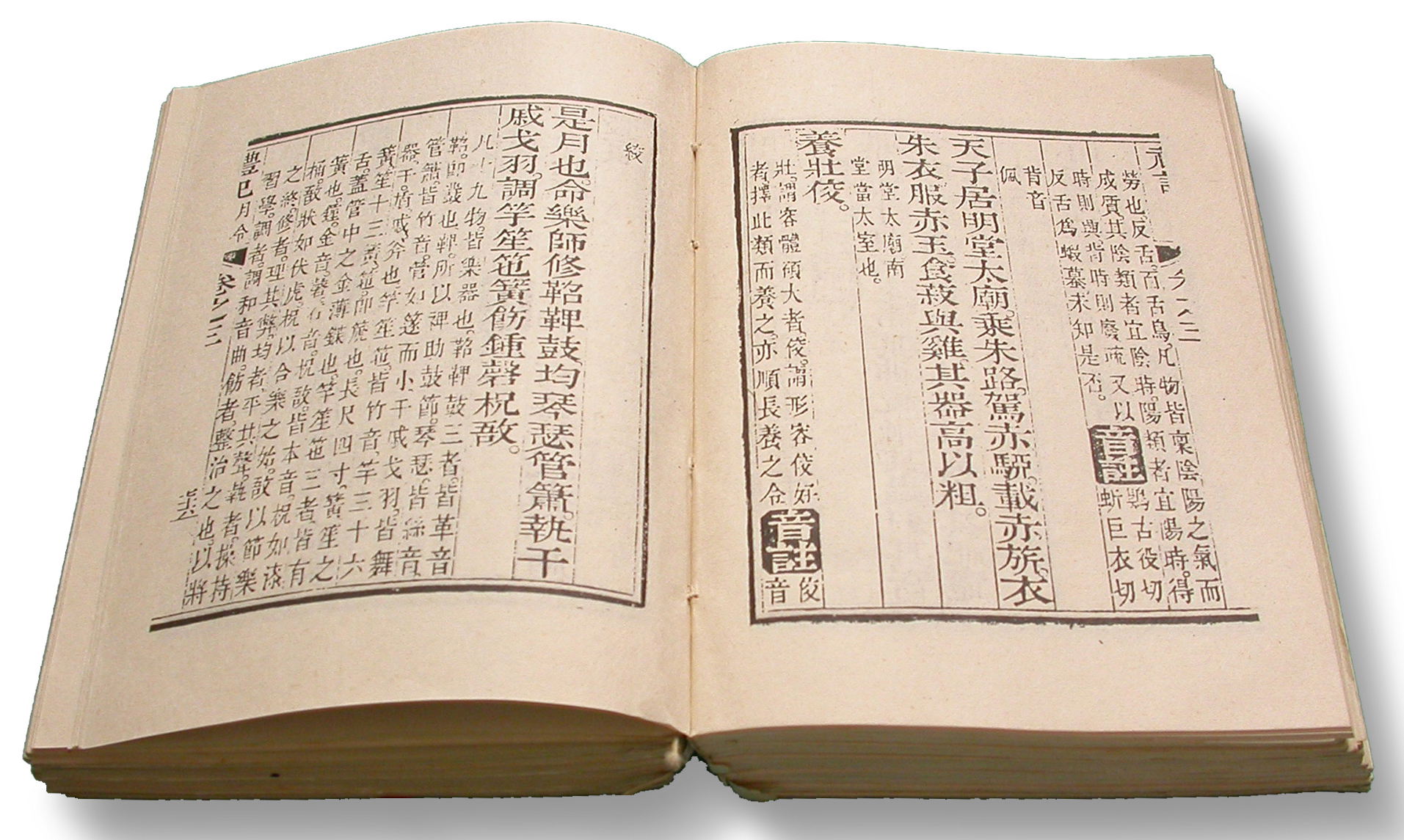

Young men who wanted to become civil administrators in China entered training schools that concentrated on calligraphy and the teachings of Confucius. Calligraphy in China equaled literacy. Chinese language is based on characters rather than on an alphabet, and is said to be the world’s oldest continually-used writing system. A dictionary published in 1039 CE listed 53,525 characters, and a 2004 Chinese dictionary included 106,230. Most Chinese words are made of one or more characters. For comparison, the English alphabet uses 26 letters and the average American has a practical vocabulary of about 10,000 words. While a foreigner learning Chinese today would be judged proficient on the national exam (the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi or HSK) with a vocabulary of about 9,000 words, they would need to know the 2,865 characters that made up these words in order to study at a Chinese university or work in a Chinese business.

In addition to literacy, civil service training focused on the philosophy of Confucius, a Chinese philosopher who had lived from 551 to 479 BCE. Kong Fuzi (Master Kong—he is known as “Confucius” in the West) taught principles derived from what he described as old Chinese classics. Confucius claimed he was not so much creating a new philosophy as preserving and combining the best traditions of the past, which was very appropriate in a culture devoted to reverence of its ancestors. He traveled as a teacher and advisor of local rulers, and his practical philosophy spread. Confucian ideas about conduct focus on five basic virtues: seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence, and kindness.

When a student asked him “Is there any one word that could guide a person throughout life?” Confucius replied, “How about ‘reciprocity’! Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself.” (Analects XV.24) The Chinese, who valued silver higher than gold, called this the silver rule. Confucian social morality is based on this reciprocity and on empathy and understanding others rather than on divinely ordained rules. Although Confucius occasionally talked about heaven and an afterlife, his moral system was not based on the idea of supernatural rewards and punishments. Confucian morality is secular rather than religious, which left room for the Emperor to be a representative of Divinity and claim “the Mandate of Heaven” without the Chinese Empire becoming a theocracy.

Centuries after his death, Confucian ideas became the basis of civil service education in imperial China. Scholars would travel to testing centers and sit for exams that often took days to complete. They brought food and a bedroll and remained in their small testing cells until they had completed the exam. There were four increasingly-difficult levels of testing: County, District, Province, and Imperial. The highest exam was administered by the emperor himself and passing it qualified a scholar for assignments in the imperial court. The exams were extremely difficult and at each level more people failed than passed. But the exams were also democratic in a way: even a scholar from a poor family could take the exam if he could educate himself; success on the top exam was a ticket to the highest levels of imperial society. Over the centuries, the scholars became an upper class in Chinese society, a gentry based on educational merit rather than merely on birth or wealth. Although there were times when the system was corrupted, for most of its history Chinese society was run by educated men rather than by nobles who had inherited their positions.

Confucianism is not a perfect philosophy, since it accepted and even reinforced certain societal injustices. Confucius incorporated traditional Chinese ancestor-worship into his system, which implied a degree of sacredness for ancestral practices. For this reason, Confucian principles perpetuated and exacerbated the oppression of women, who had no standing in the male-dominated family structure. Girls were considered an expense to their birth families, since they only became valuable when they married and bore sons for their new families. Female infanticide has been a problem throughout Chinese history, as was, until the last century, the practice of foot-binding, which rendered generations of Chinese women crippled and semi-mobile for the sake of what amounted to a fetish of Chinese fashion.

But despite its faults, Confucian civil service insured that for much of its history the Chinese empire, its various districts and regions, and even small communities were run by educated administrators and magistrates rather than by random rulers who achieved power by conquest or inheritance.

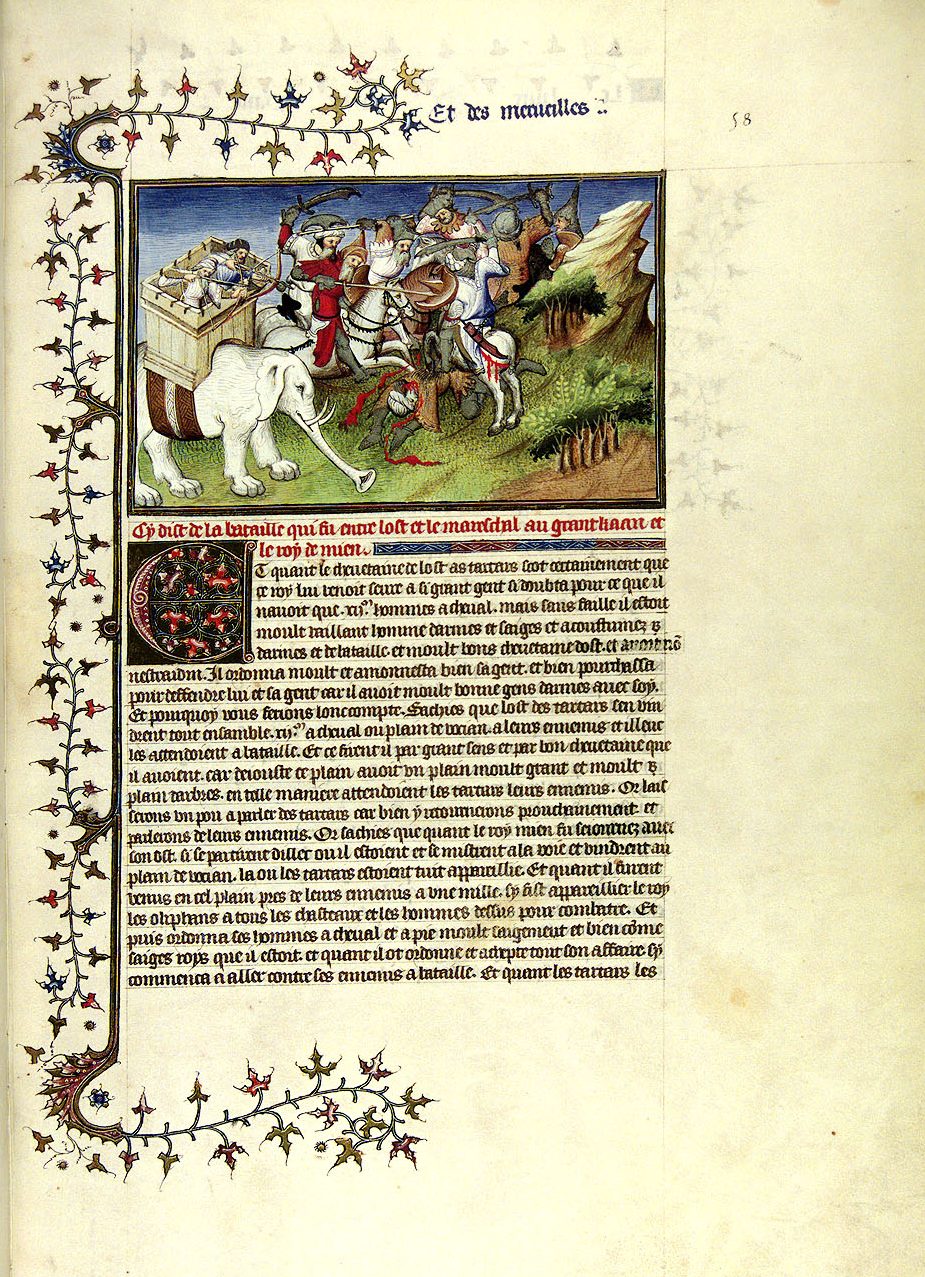

The Chinese Empire did face conquest several times, but Chinese culture and social organization managed to absorb its conquerors. In 1271, the Mongol leader Kublai Khan, the grandson of Genghis Khan, defeated the Chinese army and established the Yuan dynasty, which that lasted 98 years until 1368. Although Kublai Khan never completely conquered China despite 65 years of struggle, Yuan rule marked the first time the Chinese Empire was controlled by foreigners. The Khan distrusted Confucian officials, but he did not completely replace them as regional administrators. Still, through the Yuan dynasty, China was exposed to foreign cultures, especially Islamic cartography, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, food, and clothing, while likewise, the West encountered Chinese culture and technological advances in a serious way. The Silk Road, the ancient trade route connecting China with Europe had languished for several centuries under the Islamic Caliphate in the Middle East; it was reestablished and in 1271 the Venetian merchants Niccolo, Maffeo, and Marco Polo visited Kublai Khan at his summer palace in Shangdu (Xanadu). The Mongol rulers also patronized China’s new printing industry, which helped spread the idea of moveable type printing into Europe.

Despite the fact that China’s Mongol Yuan rulers abandoned many of their own traditions and adopted the ways of the people they had conquered, the ethnic Han Chinese majority continued to resent being ruled by foreigners. Along with exposure to foreign cultures, the Mongols’ reopening of the Silk Road brought foreign diseases to China. Bubonic Plague, the “Black Death” that killed a quarter of the European population in the 14th century, actually hit China first. The plague began in central Kyrgystan and killed up to 25 million people in China in the 1330s and 1340s, about 15 years before it first arrived in Constantinople. As in Europe, famine and social chaos followed the plague when agriculture failed to produce enough to feed the survivors.

A young man named Zhu Yuanzhang, born during the plague years, watched his entire family die in famines that swept through southern China in the 1340s. After taking refuge in a Buddhist monastery, Zhu joined local rebels when the monastery was destroyed by Yuan forces trying to contain a local insurrection. Zhu joined forces with a rebel army called the Red Turbans and rose quickly through the ranks. Zhu married the daughter of the founder of the Red Turbans and inherited his leadership position after eliminating several rival generals. In 1356, the 28-year old general conquered the ancient city of Nanjing and made it his base. In 1368, Zhu led his troops north and chased the Yuans out of their capital of Dadu (now Beijing). The Mongols retreated to Mongolia and Zhu claimed the Mandate of Heaven and declared himself the first emperor of the Ming (brilliant) Dynasty.

Zhu Yuanzhang called himself the Hongwu Emperor (expansive and martial) and made Nanjing his capital. Imperial titles like “Hongwu” relate to the reign of each emperor, in which they declare the nature of their particular rule. These titles are not the actual name of the emperor, but this is how they are known in Chinese history.

Hongwu ruled for thirty years and tried to return the empire to its ethnic Chinese roots. Hongwu issued decrees abolishing Mongol dress and requiring people to abandon their Mongol-influenced names in favor of traditional Han Chinese names. Administration of the empire by Confucian scholars was reinstated, along with the elaborate system of civil service examinations. Remembering the suffering and famines during his youth, partly caused by the flooding of the Yangtze River, Hongwu promoted public works and infrastructure projects including new dikes and irrigation systems to serve an agricultural system dominated by paddy rice. He organized the building or repair of nearly 41,000 reservoirs and planted over a billion trees in his land reclamation program. Hongwu distributed land to peasants and forced many to move to less populated areas. During his three-decade reign, China’s population recovered from plague and famine, and grew from 60 to 100 million.

Hongwu had fought his way to prominence by eliminating his rivals and trusting only his family. But when his first son, the crown prince, died, Hongwu left his throne to the son of his favorite son, rather than picking one of his other sons.. Hongwu’s grandson became emperor at 20, but his reign was a short one. His uncle Zhu Di, the emperor’s younger son, had been passed over for the crown but remained prince of a northern territory around Dadu, the previous Yuan capital close to the Mongol border. In 1402 Zhu Di overthrew his nephew and declared himself the Yongle (perpetual happiness) Emperor.

Yongle tried to erase the memory of his rebellion by purging a large number of Confucian scholars in the capital of Nanjing and moving the government to his home in Dadu, which he renamed Beijing. Yongle ruled through an extensive network of court eunuchs who formed his palace guard and secret police. Yongle repaired and reopened China’s Grand Canal, the 1,104-mile waterway that linked the Yellow and Yangxi Rivers and enabled the new capital to receive rice shipments from the south. Between 1406 and 1420, he also directed 100,000 artisans and 1 million laborers in building the Forbidden City in Beijing as a permanent imperial residence.

One of Yongle’s most trusted subordinates was the eunuch admiral Zheng He (1371-1433), the son of a Muslim soldier from southwestern China. At the age of ten Zheng He was captured, castrated, and sent to serve Prince Zhu Di in Dadu. Castration was a common practice throughout the ancient and early modern world, used in China to insure loyalty by eliminating conflict between family and duty. Educated in the prince’s household, Zheng He became a loyal soldier and later a general. Zheng He helped Zhu Di depose his nephew and take control of the empire, and the new Yongle Emperor appointed Zheng He admiral of his fleet and sent him on seven expeditions between 1405 and 1430.

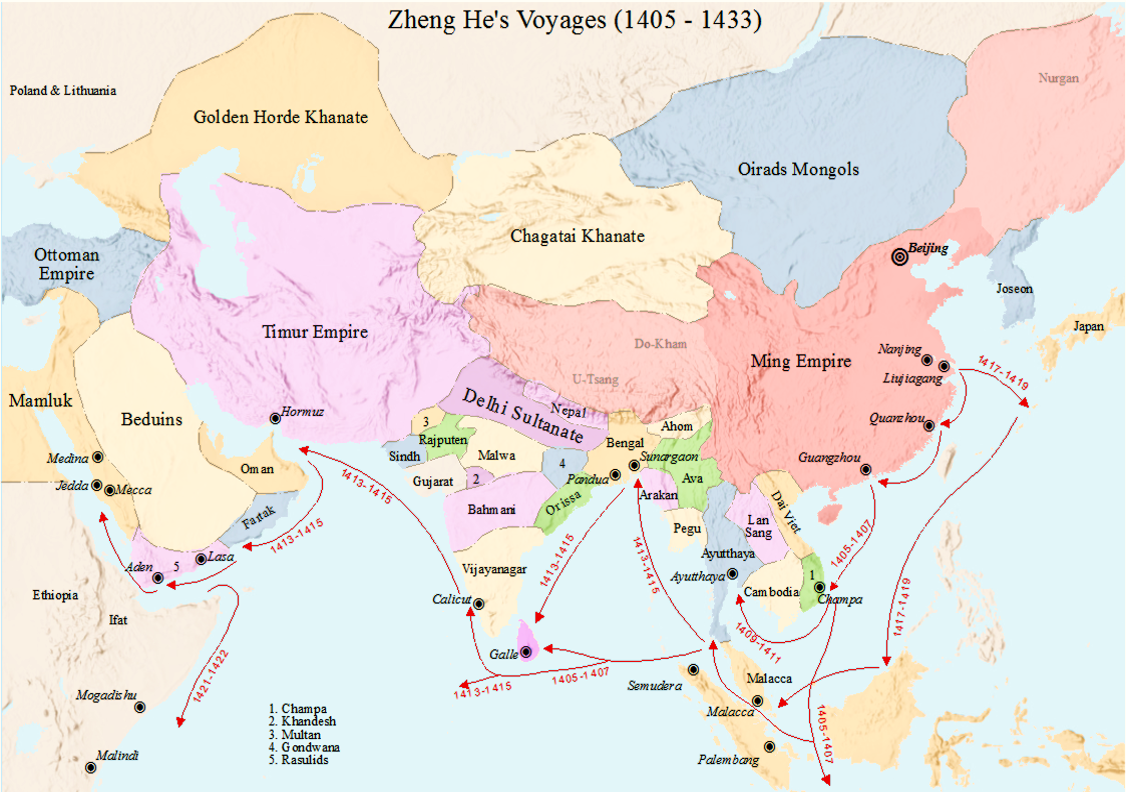

Zheng He’s first expedition left China in July 1405 with 62 large ships, over 200 smaller ships, and 28,000 soldiers. The largest ships were 425 feet long, over six times the length of the 65-foot caravels the Spanish and Portuguese would use on their explorations nearly a century later. China’s four-decked, 1,500-ton flagships had shallow drafts to allow them to navigate in river estuaries and watertight bulkheads to protect them from sinking. Their nine masts were up to two hundred feet tall and fitted with rattan sails.

Zheng He’s fleet was not interested in establishing colonies, but in exacting tribute and opening trade relationships throughout South Asia. The fleet traded for ivory, spices, ointments, exotic woods, giraffes, zebras, and ostriches; while also demanding tribute from the rulers of nations like Sumatra and Sri Lanka. Often, when local leaders seemed unwilling to submit, Zheng He seized them and brought them to Beijing where they could be convinced of the overwhelming power of the Chinese Empire. Among the places Zheng visited were Bangkok, Java, Melaka, Burma, the east and west coasts of India, Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, Jedda on the Red Sea, and Mogadishu and Mombasa on the east coast of Africa. Ninety-five delegations from Southeast Asia and other more distant nations reached the Yongle Emperor’s court during his 22-year reign, and he established a College of Translators to handle all the correspondence he received from foreign contacts. Zheng He’s seven expeditions extracted tribute from many neighboring kingdoms, and Yongle trusted him so completely that he sent Zheng He blank scrolls with his imperial seal on them, to use in whatever way he chose.

For many centuries the voyages of Zheng He were not featured in histories of China, even in China itself. As historians have rediscovered these expeditions, the superiority of Chinese naval technology has challenged the belief that western nations were the first to establish maritime power. One of the most interesting questions about Zheng He’s voyages is, “Why did they end?” China did not establish offshore colonies, perhaps partly because there was so much territory available on the empire’s northern and western frontiers. China’s rapidly-growing population was a ready market for most of the empire’s farm products and manufactures, and the international trade that interested China already found its way to the empire without much effort on China’s part. And unlike European kings, the Yongle emperor was not interested in evangelizing Confucianism or Buddhism to the rest of the world—the Spanish and Portuguese, in particular, wanted to convert the world to Catholic Christianity, which became not only a goal but a justification for conquest and colonization.

When the Yongle Emperor’s son and grandson inherited the throne, Zheng He’s expeditions gradually became less of a priority. After a final voyage in 1433, expeditions were halted and the fleet was retired and ultimately burned. Ending China’s navy was one of the major changes made by Yongle’s descendants. The burning of the Chinese fleet left a power vacuum in the South China Sea, which in the sixteenth century was filled by Japanese and Chinese coastal pirates. Finally, shortly after Yongle and Zheng He’s deaths, China was challenged from the north again. Sixteen years after Zheng He’s final expedition, Yongle’s great grandson, the sixth Ming emperor, was captured and held hostage by Mongol raiders in 1449.

The alarmed Chinese turned their attention to their border defenses and rebuilt the crumbling Long Walls into a 1,550-mile long fortification with hundreds of guard towers. The Long Walls had existed since the beginning of the Chinese Empire, but had failed to hold off Mongol invaders. Under the Mings the Great Wall was improved and extended, especially around the capital of Beijing and the agricultural heartland in the Liaodong Province north of the Korean Peninsula. These defenses enabled the Chinese population to rise from 100 million in 1500 to 160 million in 1600. However, the threat of a Manchurian land invasion from the north was taken very seriously, to the detriment of authorizing further naval expeditions. China’s turning away from the ocean was a momentous decision in world history, opening the door for Southeast Asians, Muslims, and eventually Europeans to dominate the Indian Ocean and the Pacific.

As the generations passed, Ming emperors and their courts became increasingly isolated in the Forbidden City the Yongle Emperor had built. Some were incompetent rulers, others were just uninterested in ruling. Similar to other new imperial dynasties, the Ming Dynasty began by concentrating political power in the Emperor and in the civil servants chosen through the Confucian examination process. As time passed, a ruling class grew and power shifted as the new elite protected their lands and possessions from taxation. Corrupt officials siphoned funds designated for public works into their own pockets and infrastructure such as dams and dikes crumbled. Eventually, irrigation systems failed and peasants died in widespread famines.

At the same time, Manchuria was being unified under strong military leaders who had adopted Chinese ways and who even employed Confucian administrators. In 1644, a Ming government official dealing with a local peasant insurrection that threatened Beijing asked the Manchurians for military aid. Of course, once the Manchu armies were past the Wall, there was no way to send them back. They took control of Beijing and declared the end of the Ming Empire and the beginning of a new dynasty, the Qing (pure).

We will return later to the history of China, the Qing Dynasty, and what came after. For now, the point of beginning modern world history with China is that in terms of population and economic power, it was the center of the world in 1500 when our survey of Modern World History begins. In 1500, the Chinese population was growing rapidly, the Ming Empire had a standing army of over a million soldiers and the Chinese navy of Zheng He had recently projected the empire’s power throughout Asia. The Chinese economy produced one quarter of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 1500, followed by India which produced nearly another quarter. In comparison, the fourteen nations of western Europe produced just about half of China’s GDP or only one-eight of the global total production. The largest European economy, in Italy, produced only about one-sixth of China’s output.

The Ming Empire’s population in 1500 was about 125 million. The next largest empires were Southern India’s Vijayanagara Empire (16 million), followed by the Inca Empire of South America (12 million), the Ottoman Empire (11 million), the Spanish Empire (about 8.5 million), and the Ashikaga Shogunate of Japan (8 million). Keep the immense mass of China and the gravity exerted by its economy in mind as we move on to discuss events like the creation of a Spanish colonial empire in the Americas—Spanish-American mines produced the silver that accidentally became the world’s currency, filling not only the treasuries Europe, but also that of China in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Media Attributions

- Liji

- Half_Portraits_of_the_Great_Sage_and_Virtuous_Men_of_Old_-_Confucius

- Palastexamen-SongDynastie

- 4079285574_60bc820530_b

- Mongol_Empire_map

- Marco_Polo,_Il_Milione,_Chapter_CXXIII_and_CXXIV

- Hongwu1

- 8139576703_a585a2d543_b

- 3668431041_d826f18308_b

- 361639903_8ff8b7b616_b (1)

- Voyages_of_Zheng_He

- Verbotene-Stadt1500