10 Decolonization

The defeat of Germany and Japan freed the people of the nations these two would-be empires had conquered, but it also caused people dominated by older empires to question the legitimacy of imperialism. In many of Europe’s and the United States’ imperial possessions, the struggle for independence had begun long before World War Two, however. As you’ll recall from previous chapters, European and American justifications for empire included the claim that people such as Britain’s subjects in India and the America’s in the Philippines were unprepared to stand on their own as independent nations. This claim was undermined by the effectiveness of the Indians and Filipinos in World War II. Filipinos had proven their value as guerrilla fighters. The Japanese only managed to control twelve of the forty-eight provinces of the Philippines, and U.S. General Douglas MacArthur said, “Give me ten thousand Filipinos and I shall conquer the world!” And in imperial possessions like India, the “civilizing project” of empire for generations had including educating local administrators and training military and police forces. The leaders of national liberation often came out of these experiences reasoning that since they were already experienced at running their own nations as administrators for the empires, it was time for the imperialists to leave. Furthermore, the war was full of inspirational examples of Europeans and Asians who fought side by side against the fascist occupiers in their conquered nations. The process was accelerated by the strain of war on the European imperialists. France and the Netherlands had been conquered and themselves occupied as imperial subjects by the Germans, while the British were greatly weakened.

After the war, the nations that had been targeted by Germany (Britain, France, and the Netherlands) all attempted to separate their reaction to this attack from the response of colonial populations to their return. For instance, British leaders like Winston Churchill hoped and expected to expand their empire, which they now renamed a commonwealth, and the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP) had no intention of giving back Iran’s oil fields. This may seem a strange attitude for a nation that was having trouble feeding and housing its own population and leaned on U.S. aid like a crutch. But the British retained their sense of cultural superiority and convinced themselves that their help was still needed to “assist primitive peoples in their march to modernity.”

The timing of national liberation was complicated by the growing conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, which was both a competition to dominate territory and control alliances as well as an ideological struggle between capitalism and communism. This conflict was known as the “Cold War,” since the two countries never directly attacked one another. Instead they fought a series of proxy wars that occurred within the context of decolonization. Each superpower competed to recruit more new nations to their side, pouring military and economic aid into the new developing countries.

Despite the Cold War, at times the process of independence was peacefully achieved through mutual agreement. In the Philippines, for example, the U.S. government handed over power to a local Filipino government within a year of ending the war with Japan. The Americans fully appreciated the sacrifices made by the Filipinos under Japanese occupation and the contributions they had made to their own liberation. President Harry Truman recognized the independence of the Philippines on July 4, 1946. In the days leading up to the announcement, the American and Filipino governments worked out arrangements allowing the U.S. to retain dozens of military bases and for American businesses to have preferential access to the raw materials and markets of the newly independent nation.

Sometimes, peaceful political pressure from organized movements also led to liberation. Indian independence, examined below, is the first and prime example of how non-violent protest, boycotts, and moral suasion could result in freedom. However, there are also many cases in which independence could only be achieved through a more violent guerrilla struggle, as European imperialists were unwilling to let go of their colonies despite the desires of the colonized.

Independence and Partition in British India

One of the earliest examples of decolonization in the post-war era and one that affected an extremely large portion of the world’s population was the British withdrawal from India. As mentioned earlier, India’s long struggle for independence had been led by the India National Congress Party since the nineteenth century.

After 700,000 Indians fought for Britain in the Great war, over 2.5 million soldiers from India fought alongside the British in World War II. More than 87,000 of them were killed in action. The British Field Marshall in charge of the Indian Army from 1942 onward said Britain “couldn’t have come through both wars [World War I and World War II] if they hadn’t had the Indian Army.” When Britain called Indians to arms a second time, the Muslim League supported the British recruitment. However, the Indian National Congress demanded independence before it would agree to help Britain again. When the Congress began a “Quit India” campaign in August 1942, the British imprisoned tens of thousands of leaders for the war’s duration until June 1945. Mohandas Gandhi was among those jailed; he was released in May 1944 due to health concerns.

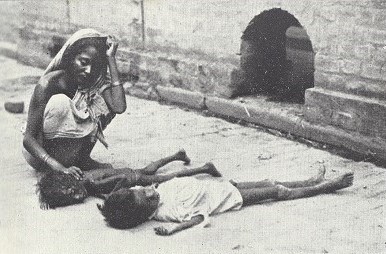

British war strategy led to a major famine in Bengal in 1943 (modern-day Bangladesh, at the mouth of the Ganges River), and about 3 million people died of starvation. The Japanese invasion of Burma caused about a half million Indian Hindu refugees to flee to neighboring Bengal. At the same time, the British decided to adopt a “scorched-earth” policy in southern Bengal, burning thousands of boats and destroying rice crops so they would not fall into the hands of the Japanese, who they assumed would soon extend their invasion. Poor harvests and wartime inflation in late 1942-early 1943 sent internal rural refugees into Calcutta, the Bengali capital, exacerbating the crisis. The British War Cabinet stalled in sending needed grain to the starving Bengalis—perhaps as policy, perhaps because of the strain on wartime shipping. Very little sympathy was shown for the plight of the Bengalese by the leaders of Great Britain. When presented with evidence of the massive famine, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was incredulous, reportedly asking, “Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?”

Churchill was not only aware of Gandhi, he was aware of the importance to India to the British war effort. In addition to 2.5 million soldiers, the British government borrowed billions of pounds from India to finance the war. And India was no longer merely a site of famines, it was becoming a source of essential supplies. By the end of the war, India had become the world’s fourth largest industrial power and its increased economic and military influence paved the way for independence from the British Empire in 1947.

However, Indian independence was complicated by internal divisions, some exacerbated by the British themselves during many decades of imperial rule. In particular, the British had encouraged division between the majority Hindu and minority Muslim populations; sending Hindu troops to police the Muslims, and vice versa. Gandhi sought to eliminate the Hindu caste system which deprived the poorest Indians of hope. Castes were an integral part of Hinduism, but under British rule the system had been expanded and the number of divisions had been increased because the foreign rulers found it useful in their divide-and-conquer strategy.

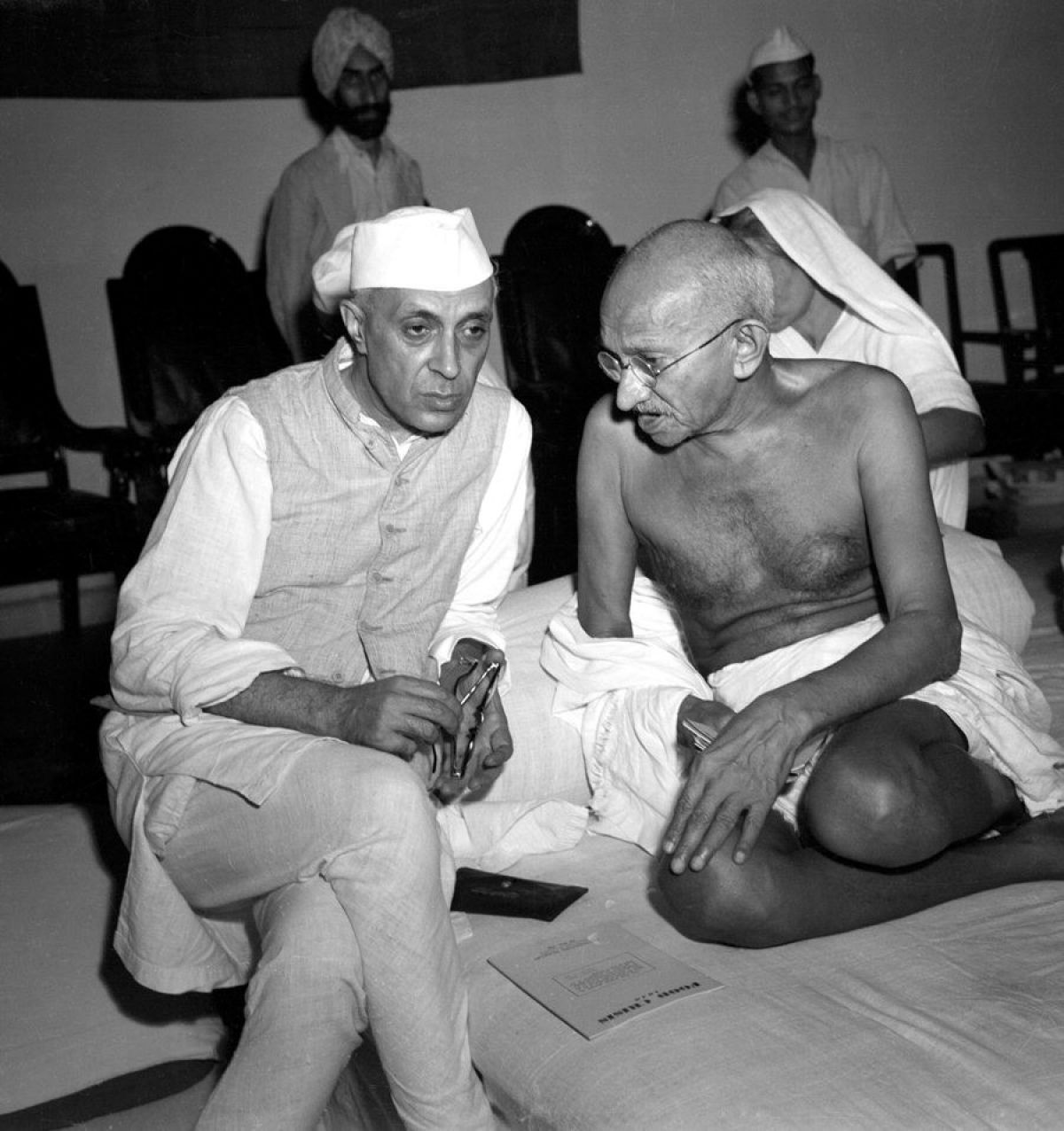

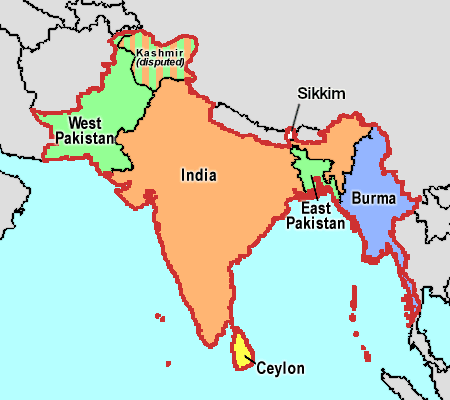

Religious divisions seeped into the independence movement as well. While Gandhi simply wished for an independent, united India after the end of British rule, Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League lobbied for the establishment of two states in the territory. Jinnah proposed the creation of a Hindu India and an Islamic “Pure Land” called Pakistan. Jinnah’s position was embraced by Hindu nationalists who wanted to be rid of the Muslim minority. As independence was being negotiated after the war, escalating religious violence suggested that British withdrawal might result in a bloody civil war. Muslims and Hindus attacked each other in different towns and cities, so Congress Party leader Jawaharlal Nehru (who would become the first Prime Minister of India) accepted the partition of India from Pakistan. The new Muslim nation at the time included both the present territory of Pakistan in the west and the eastern region now called Bangladesh.

After independence in August 1947, the partition created a central Hindu nation with two borders into Muslim Pakistan to the east and west. These new, arbitrarily-drawn borders resulted in the displacement of 12 million people, as the former British subjects fled their homes to join the new nations that matched their religions. Millions died during the chaos of the migration and the refugee crises that followed. But even partition was not enough for some Hindu nationalists. Gandhi himself was assassinated by one such extremist shortly after he achieved his dream of independence, in January 1948.

Not only was partition an imperfect solution to religious differences the British empire had exacerbated, but the arbitrary borders were drawn hastily. The state of Kashmir in northern India is still disputed territory. In 1947, a local Hindu prince convinced the British that the majority-Muslim region should stay with India. The Government of Pakistan and many local Kashmiris continue to protest this, causing internal and external conflicts. Since both India and Pakistan are now nuclear nations, the ongoing Kashmir dispute is a legacy of imperialism that may still endanger regional or even global peace.

Israel

India was not the only region of the world from which Britain walked away soon after World War Two. Another was Palestine. After World War I, Britain had been given a “mandate” to administer Palestine along with the oil-rich regions of Arabia and Iraq. Between the wars the British continued to allow Zionists, advocates of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, to purchase land and move into the region. Migration of Zionist Jews to the region had begun in the late nineteenth century. This “second wave” of Zionist settlers included dedicated socialists who created cooperative farms called kibbutzim, and urban Europeans who built cities like Tel Aviv—one of the prime examples of the Bauhaus architectural style popular in Germany in the 1920s. However, accelerating Zionist immigration increased tensions with the Palestinian Arabs who had lived in the region for centuries. Competition for land and water, as well as for political dominance, resulted in violent riots between Arabs and Zionists in 1921, and a longer Arab revolt in Palestine from 1936 to 1939.

As mentioned previously, the Nazi Holocaust seemed to prove the Zionist thesis: that Jews would never be safe in Europe and needed to establish their own homeland. The British considered a petition to allow 100,000 refugee survivors of the Nazi camps to resettle in Palestine, but hesitated due to opposition from Palestinian Arabs and the nearby Arab states. Zionist settlers had already formed a mutual defense force, the Haganah, in the 1920s. After the war, the Haganah turned to sabotage against the British occupation and organizing illicit arms shipments.

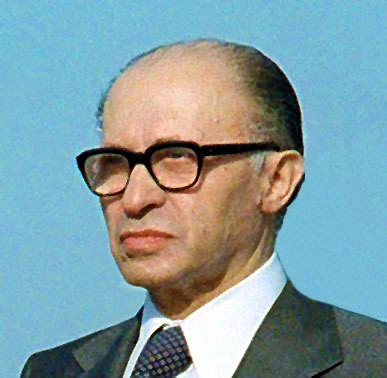

More radical terrorist organizations also formed, including the Irgun, which in 1946 bombed the British headquarters at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 people. The Irgun also led a terror attack on the Palestinian town of Deir Hassin in 1948, in which over a hundred perished, including women and children. Despite apologies from more mainstream Zionist groups (and, later, the Israeli government), the Deir Hassin massacre has served as a rallying cry and a justification for terror attacks against Israelis by different Palestinian-related terrorist groups ever since.

In 1947, the British relinquished their “mandate” over Palestine to the new United Nations, which tried to develop a new map for a Jewish homeland—the new state of Israel—while taking into account the presence of the Arab Palestinians. The Zionists received more land than could be justified by their numbers at the time, as well as some of the more valuable agricultural and water resources. As the British withdrew in May 1948, Israel declared its independence based on the U.N. borders, which the both the local Arabs and the neighboring Arab countries had rejected. Israel’s new neighbors immediately declared war, but the new nation had powerful allies and was willing to fight for its survival. Israel defended itself and actually extended its borders. The Israelis claimed they needed to have a wider defensive perimeter and that the Arab Palestinians had abandoned many of their towns anyway; which many had because they thought the Arabs would win a decisive victory. Israel eventually destroyed over 500 Arab villages and cleared out Arab neighborhoods in major cities, causing the over 800,000 “temporary” Muslim and Christian war refugees to seek more permanent shelter in neighboring Arab nations. A series of wars in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982 continued the conflict.

With tenacity, superior organization, and a lot of aid from the United States and Europe, the Israelis held their own in these conflicts and embraced an ongoing expansion of the Israeli area of settlement in a policy of creating “facts on the ground.” The Arab world, considering Israel an arbitrary creation of western powers, refused to recognize Israel as a legitimate state. Peace processes with individual Arab nations have brought agreements and diplomatic recognition from Egypt in 1979, to whom Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula, taken in the 1967 war; and Jordan in 1994, which relinquished its claim to the Palestinian West Bank of the Jordan River.

Weariness with war and terror, and a desire to qualify for U.S. military and economic aid, have led the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Sudan to recognize Israel in 2020. But it is one thing to have recognition from a government, and another thing to be accepted as a nation by the “Arab Street”. Ordinary Arab people are often tired of authoritarian rule in their own countries, and are more supportive of the Palestinian Arab cause than the governments ruling them.

“British” Kenya

Although Great Britain had retreated relatively peacefully from India and had given up its control over Palestine voluntarily, this was not the universal pattern. Reluctance to abandon colonies was especially a problem in Africa, where there were British settlers rather than administrators. By the early twentieth century, 30,000 British settlers occupied all the best farmland in Kenya, which they had bought or had been assigned by the colonial government, leaving 5 million Kenyans without. The settlers were people something like the Dane Isek Dinesen, who wrote of her experiences in Kenya in her 1937 book Out of Africa, although most were generally less respectful and interested in the natives than she. More were like farmer Mike Blundell, a white man featured in a Life Magazine article who had arrived as an unskilled farm apprentice but because he was white had managed to get hold of 1200 acres of “virgin bush.” Blundell despised the local Kikuyu tribes and believed the “Kukes” as he called them had only “come out of the trees” in the last 50 years, and probably as a result of contact with the whites. The attitude of British farmers in Kenya was much like the relationship two centuries earlier between English colonists in North America and the Native Americans.

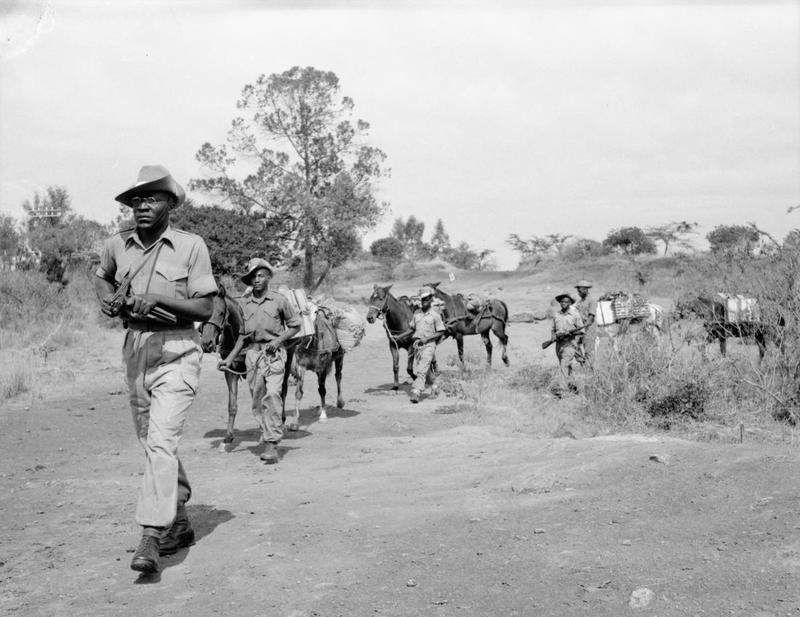

But this was the twentieth, not the eighteenth century. In Kenya, a resistance movement called Mau Mau began in 1952 when natives restricted to reservations in their own country revolted. After World War II, 1.25 million Kikuyu had 2,000 square miles of marginal farmland to feed themselves while 30,000 British settlers had 12,000 square miles in the fertile hills of the Central and Rift Valleys, where they grew cash crops like coffee using native labor. The Mau Mau uprising protested this injustice and the British colonial government responded. Declaring a state of emergency, the British moved about 450,000 Kikuyu to concentration camps and another million were restricted to “enclosed villages”. Prisoners suspected of being Mau Mau fighters were often tortured by British troops (typically they were flogged to death, burned alive, or castrated). In June 1957 the British attorney general of the colony wrote to the governor that the mistreatment of captives was “distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or Communist Russia.” He reminded the governor, “if we are going to sin, we must sin quietly.”

The uprising lasted until 1963, partly because white settlers could not easily abandon their property and go back to Britain. Power in Kenya eventually shifted from the British colonial government to a native government, initially made up of many members of the Kenyan African National Union (KANU) that had led the resistance. Its leader, Jomo Kenyatta, became Kenya’s first indigenous Prime Minister from 1963 to 1964 and was President of Kenya and led the KANU party until his death in 1978. Kenyatta, like other leaders such as Gandhi and Ho Chi Minh, had travelled internationally. He attended the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow as well as University College in London and the London School of Economics, although when the press mentioned him, they typically observed he had “studied in Russia”. Kenyatta was imprisoned from 1954 to 1961 for allegedly leading the rebellion, and became leader of the party and the nation when released. Kenyatta initially tried to heal the nation by downplaying the atrocity of the recent war, and he welcomed the multinational corporations that dominated the Kenyan economy. The government helped African farmers buy out white landowners and expanded education and social support programs. Kenyatta was often accused of being a socialist, but he was also hated by the British settlers for being married to a white woman. His economic policies balanced capitalism and social welfare. Kenyatta was regarded by many Africans as a strong Pan-Africanist and was hailed as the Hero of the Kikuyu.

“French” Algeria

The British were not the only Europeans to lose their colonial empires. Although France had been conquered and occupied by Germany, after the war the French fully expected to regain their colonial possessions in Africa and Asia and resume where they had left off. Their subject peoples in the colonies had different ideas. In Algeria, revolutionaries had been organizing to resist French imperialism since before the war. An Algerian People’s Manifesto was published in 1943. On the morning of May 8, 1945, (the day that Nazi Germany surrendered, or VE Day), a parade of about 5,000 Muslim Algerians celebrating the war’s end was met by armed French police. Marchers and police exchanged gunfire and during the battle people on both sides were shot. A few days later a smaller, peaceful protest by the Algerian People’s Party was violently repressed by police. Rural Algerians responded by attacking ethnic French settlers, called pieds noirs, killing 102 Europeans. The French retaliated, killing between 6,000 and 30,000 Algerians.

The Algerians did not forget this massacre and nearly a decade later, on November 1, 1954, Algerian guerrilla forces attacked civilian and military targets throughout the country. The National Liberation Front (FLN), encouraged by the fact France had just lost their colony of French Indochina, called on Muslims in Algeria to join in the struggle for independence. The FLN applied guerrilla “hit and run” tactics as well as terrorism and torture of both French pieds noirs and Africans suspected of supporting the regime. The French were equally brutal, and by 1956 there were more than 400,000 French troops in Algeria.

The war lasted eight years and killed over a million people. The French military lost 25,000 troops and about 3,000 European civilians were killed. French officials estimated the Algerian death toll at 350,000, but other French and Algerian estimates range from 960,000 to 1.5 million. The United States recognized Algeria’s independence in September 1962 and the country became the 109th member of the U.N. in October.

“French” Indochina

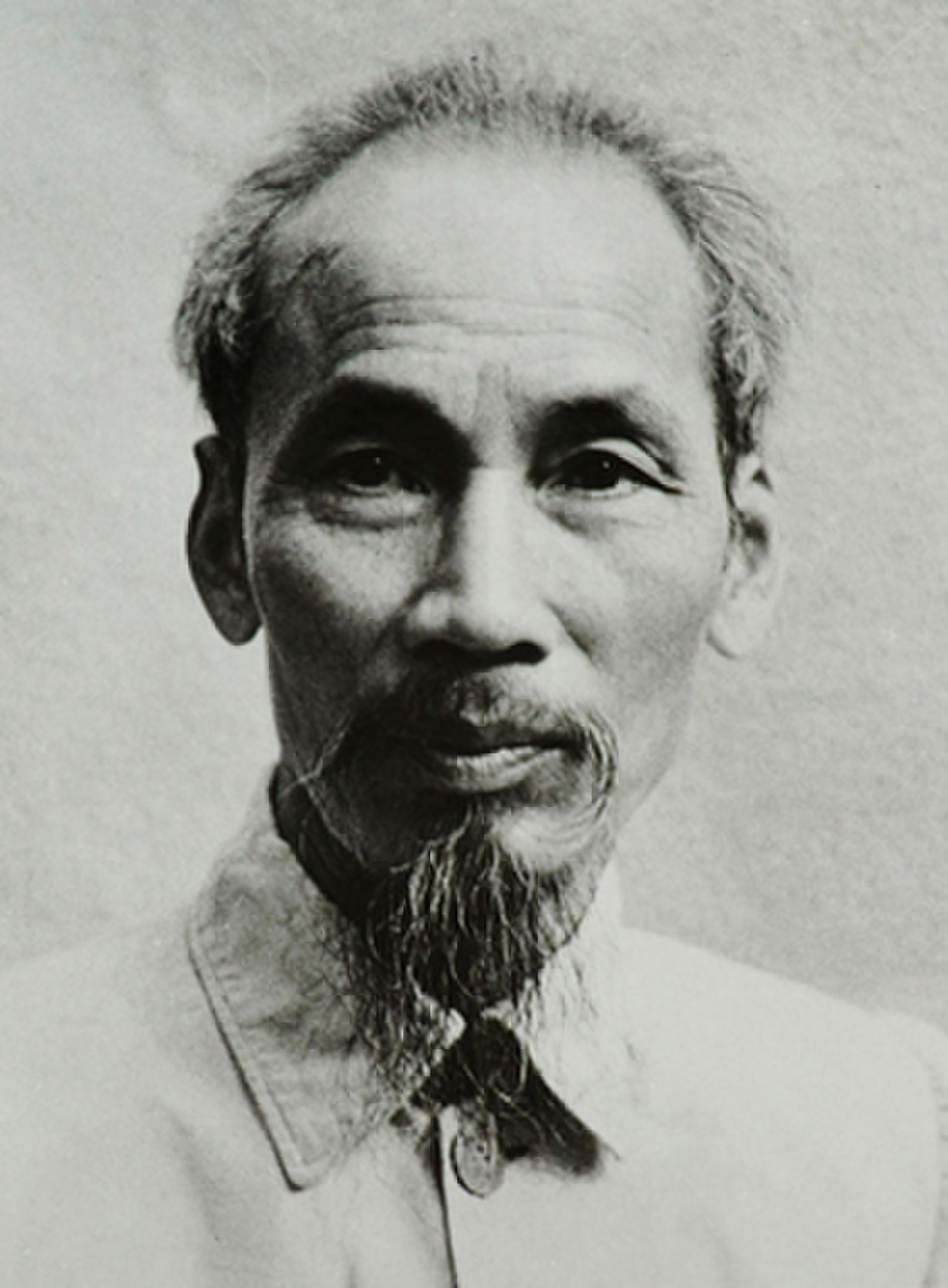

France had also expected to return to power in its colonies in French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia), but the people living there also had other ideas. Revolutionaries were led by Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969), who as a young man had worked as a kitchen helper on a steamship from Saigon to Marseille in 1911. Ho actually applied to the French Colonial Administrative School in Marseille, but his application was rejected and he returned to working on ships and traveling the world for another five years (it’s interesting to imagine how history would have been different if he had been accepted). He visited the U.S. several times in his travels and later claimed to have met Black nationalist Marcus Garvey. Ho worked in England and France between 1913 and 1919. He joined a group of Vietnamese nationalists in Paris, and at the end of World War I, the group petitioned at the Versailles peace talks for recognition of the civil rights of Vietnamese people, citing Woodrow Wilson’s statements about self-determination in the famous “14 Points” speech. Ho wrote a letter to Wilson, but the American President ignored him.

Rebuffed, Ho continued living in France in the early 1920s, meeting socialists and becoming a founding member of the French Communist Party. Ho began to write articles that were noticed in Moscow and he was invited to visit the Soviet Union. In 1923, Ho studied at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in Moscow before moving to Guangzhou China in 1924. When Chiang Kai-shek cracked down on communists in China, Ho returned to Moscow and then moved on to Thailand. In late 1929 he moved through India to Shanghai and Hong Kong. By this time, he was becoming well-known in revolutionary circles. Ho was arrested in Hong Kong in 1931 but escaped and returned to Russia.

In 1938 Ho returned to China as an advisor to the Chinese Communist army. In 1941 he returned to Vietnam to lead the independence movement there. The Japanese invasion created an opportunity for the patriots, who were aided in their resistance of the Japanese and Vichy French by the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA. At the end of World War II, Ho wrote a declaration of independence for Vietnam based on the US Declaration from 1776. Ho repeatedly petitioned President Harry S. Truman to recognize Vietnam, citing the Atlantic Charter, but Truman never responded. Meanwhile, British and Chinese troops occupied the country in support of France. Vietnamese rioted and killed a hundred or so French citizens, and in retaliation French troops armed Japanese prisoners of war and massacred over 6,000 Vietnamese. This was the same pattern of asymmetrical force used by empires against their subjects throughout the colonial period. However, the story of Vietnam is only half over; we will return to it in the next chapter when we discuss the Cold War.

Kenya, Algeria, and Vietnam were not the only places where the imperial powers and their international allies responded violently to movements of national liberation among the colonized. For example, the French killed 80,000 in Madagascar in 1947 when the people of that island supported independence. The Indonesian War of Independence raged from the former Dutch East Indies declaration of independence in 1945 and The Netherlands’ recognition of their claims in 1949. About 8,000 Dutch troops and their allies were killed, and about 100,000 Indonesians. And growing fears of international communism pushed the United States government into supporting some of these actions. Although the Americans had peacefully let go of the Philippines, the U.S. military helped Korean militias massacre about 60,000 members of a peasant insurgency. The Korean Peninsula had been divided at the end of World War Two, like Germany, into Soviet and U.S. occupation zones. Unsurprisingly, the two rivals backed communist and non-communist leaders in North and South Korea. The resulting conflict, the Korean War (1950-1953), will be examined in more detail in the next chapter on the Cold War.

Media Attributions

- American_military_personnel_gather_in_Paris_to_celebrate_the_Japanese_surrender

- Winston_Churchill_waves_to_crowds_in_Whitehall_in_London_as_they_celebrate_VE_Day,_8_May_1945._H41849

- The_Fighting_Filipinos_-_NARA_-_534127

- INDIAN_TROOPS_IN_BURMA,_1944

- Dead_or_dying_children_on_a_Calcutta_street_(The_Statesman_22_August_1943)

- Gandhi_and_Nehru_in_1946

- Partition_of_India

- Zina_Dizengoff_Circle_in_the_1940s

- Menachem_Begin_2

- 2c0ee9f4f58a2d9232f737498250c8e3

- Jomo_Kenyatta_1966-06-15

- KAR_Mau_Mau

- 2560px-Ho_Chi_Minh_1946

- Ho_Chi_Minh_(third_from_left_standing)_and_the_OSS_in_1945