4 Early Globalization and Revolutions

The Development of Nation-States in Europe

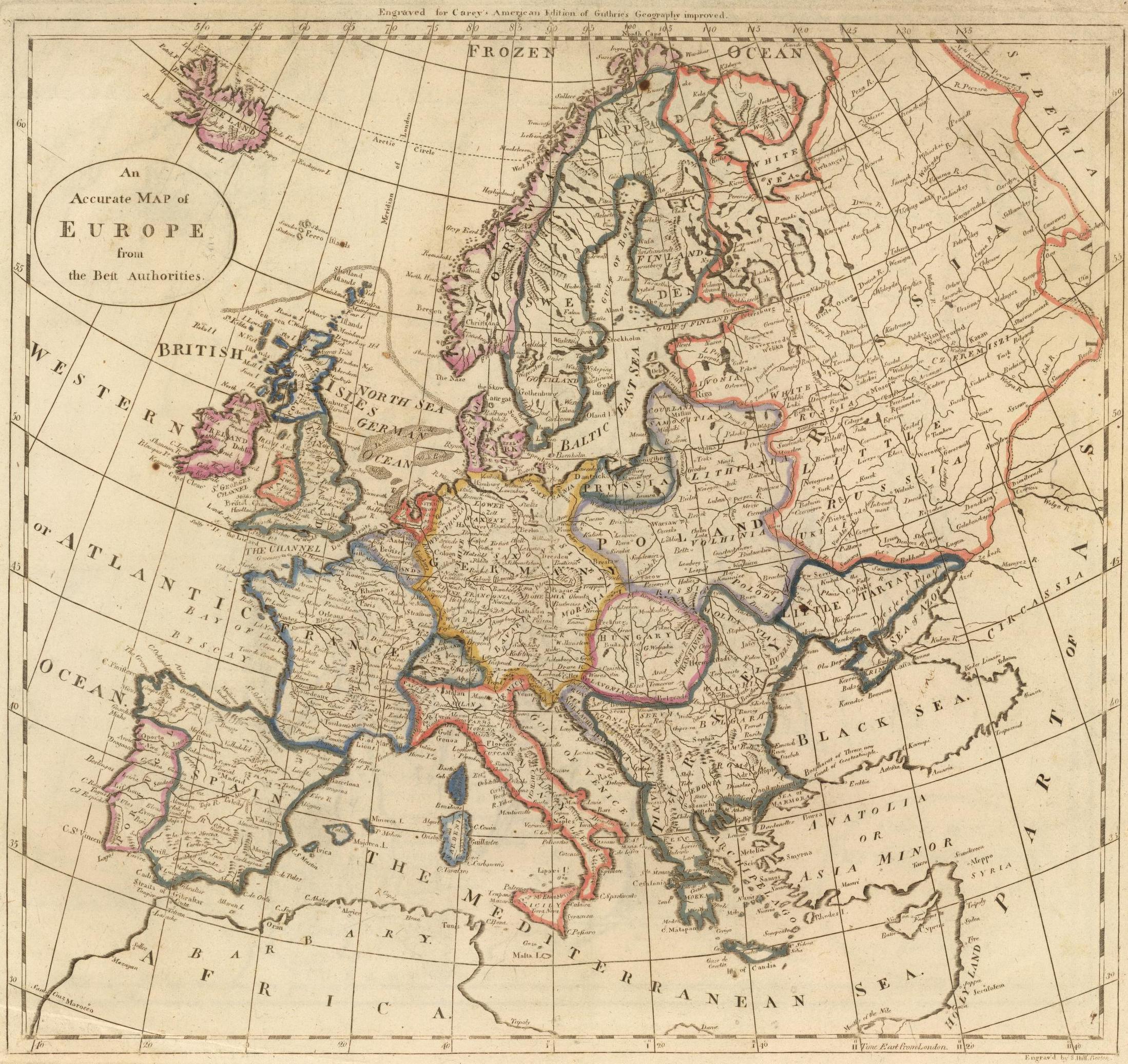

As mentioned previously, by 1500, Western Europeans were unable to pull themselves together into the type of extensive land empire seen in Asia at the time – or to reconstruct the unity that had been achieved in the Roman Empire. The Hapsburg family continued to try to maintain an entity they called the “Holy Roman Empire” but it was really an alliance of German principalities, and had ceased to include Rome in the 12th century. During the 1600s, religion, language, and local culture began inspiring feelings of regional solidarity that grew into the idea of separate nationalities. Some of these nations organized themselves as absolute monarchies, while in others, power was shared among different national groups.

The consolidation of nationalities happened over several centuries. By 1500, Europe’s 80 million people were divided into about 500 states and principalities. Three hundred years later, Europe’s population had nearly doubled and 150 million Europeans lived in just 30 nations. In many of these countries, the ideas of divine monarchy and hereditary nobility had given way to a sharing of constitutional power between rulers and their subjects. Merchants gained influence and slowly acquired legislative powers in bodies like Britain’s House of Commons.

The French Revolution, inspired in part by the revolt of Britain’s North American colonies and the establishment of the United States, would extend the experiment with democracy to include the lower classes for the first time in European history. France’s revolution, which will be presented in this chapter, would end one of the most deeply-entrenched absolute monarchies of Europe, while Napoleon’s armies ended feudalism in most of continental Europe by 1815.

European Colonization of North America

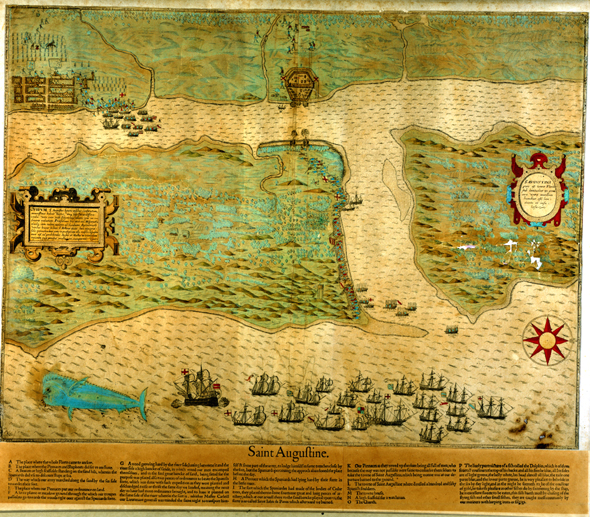

The Spanish established the first permanent European settlement on the North American coast in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1565. The French followed two decades later, building a fort in 1604 at Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia and establishing Quebec on the St. Lawrence River in 1608. The English had tried settling people on Roanoke Island, in North Carolina, in 1588, but the colony had mysteriously disappeared by the time resupply ships returned to the area a few years later. The settlement may have been overrun by local Indians, but it is also possible that the abandoned colonists went to live with the natives when their food ran out and when help failed to arrive from England. Throughout the early history of English settlement in North America, colonial authorities regularly tried to hush up reports of poor English colonists choosing to live with the Indians. The English published frightening tales of captivity and redemption, although in reality poor people, especially women, were often better-treated in Indian society than in the English colonies.

After losing both their people and their entire capital investment at Roanoke, the English waited nearly 20 years before they tried settling the Chesapeake Bay region again in 1607. The Virginia Company, a joint stock venture chartered by King James I in 1606, sent expeditions to the explore the coast of North America between the Spanish and French settlements, one of which established Jamestown forty miles inland on the James River as the first permanent English town in North America. In 1620 a shipload of persecuted Puritans we know as the “Pilgrims” fled England and its Anglican church and landed on Cape Cod. Ten years later another group of Puritans received a royal charter to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony at Boston.

British colonists in North America focused on establishing family farms for raising crops and pasturing animals like cattle and sheep, and growing cash crops like tobacco in the warmer climate of the South. By contrast, French efforts on the continent centered on trade with Indians for beaver pelts, since the growing season was much shorter in the region between the St. Lawrence River and Hudson Bay. Many French voyageurs married native women, creating the mixed-ethnic community known as métis today. However, alliance with the Indians did not change the outcome of the Seven Years War for France in 1763, as we will see in a bit. The French still lost all their North American territory to the British and Spanish (Napoleon later got the Louisiana Territory back, then almost immediately sold it to Thomas Jefferson).

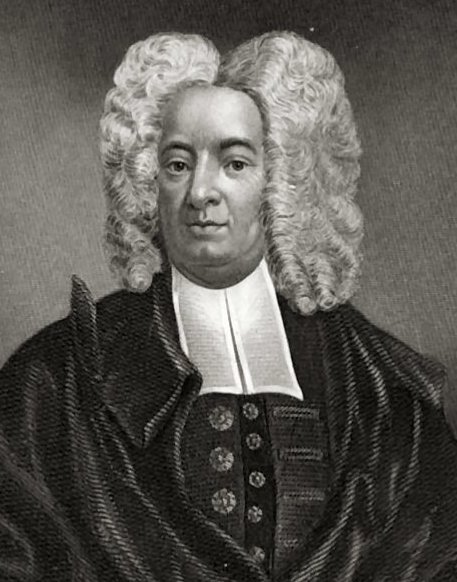

The diseases of the Columbian Exchange spread more slowly in places where Indian population density was comparatively lower, such as along the Atlantic Coast of North America. But once again, it worked to the advantage of Europeans. Native populations in the coastal northeast were devastated by an epidemic that raged from 1617 to 1619 and killed 95 percent of the Abenaki people and over 90 percent of the Massachusetts tribe. This emptying of the land was often seen by English settlers like the Pilgrims and the Puritans as a gift of divine providence. Puritan leader John Winthrop wrote about the favor God had shown to the colonists by killing the natives and minister Cotton Mather wrote that “The Indians of these parts had newly…been visited with such a prodigious Pestilence; as carried away not a Tenth, but Nine Parts of Ten (yea, ‘tis said Nineteen of Twenty) among them…So that the Woods were almost cleared of those pernicious Creatures, to make Room for better Growth” (Magnalia Christi Americana, 1702). English colonists were quick to take advantage of the empty village sites, open farmland, and social chaos among the natives caused throughout the region by the ongoing Columbian Exchange.

Although many individual settlers probably tried to deal fairly with their Indian neighbors, the differences between European and native ideas of ownership and the rapid growth of the colonies made conflict virtually inevitable. Natives regularly moved to new locations as the seasons changed. They gardened in shifting fields. Colonists built houses and permanent villages, and fenced their fields. But although they claimed complete ownership of the parcels they occupied, the colonists let their cattle and pigs run loose over the countryside. Since the natives were not protecting their lands in ways the colonists recognized, with fences, the Euro-Americans believed (or at least argued) Indians had no idea of land ownership. The colonists were unaware that native practices had been created for a world without domestic livestock. When Indians treated European livestock like wildlife and shot a wandering cow, or when they killed pigs eating their un-fenced crops, the colonists demanded compensation for the destruction of their property. And of course, more colonists arrived every year. The Powhatan wars in Virginia (1610-46), the Pequot War in Connecticut (1637), the Dutch-Indian War in the Hudson Valley (1643), and the Beaver Wars (1650) all ended badly for the natives. Even King Philip’s War (1675), which is remembered as a disastrous, nearly-successful uprising by Massasoit’s son Metacomet, who had finally decided enough was enough, resulted in five times as many native deaths as English. By the conclusion of the worldwide Seven Years War between the French and British empires (known as the French and Indian War in North America) in 1763, northeastern natives were no longer considered a threat to European colonies.

Comparative Colonization: The Spanish, the British, the Land, the Natives

The contrasts between Spanish and British colonization in the Americas are stark, and help explain subsequent social and economic development in the Hemisphere. The differences are especially visible in four areas: who the settlers were, how they were governed, how they worked the land, and the nature of their relationship with the indigenous peoples.

As described in the previous chapter, the Spanish had just completed an 800-year “Reconquest” of Iberia from Muslim rule in 1492, when Columbus first sailed west. Spain applied the same model of Iberian conquest and colonization to the Americas, granting conquered land with all of its inhabitants to the encomenderos, who were selected for their proven loyalty to King and empire, and to the Catholic Church. Soldiers and clergy were also pledged to Crown and Church, as well as the administrators, artisans and other settlers who arrived in Spanish America with their families. The Portuguese in Brazil followed the same rule.

The British, however, used their colonies in North America as havens for religious dissenters, as a safety-valve to reduce the numbers of the poor in England, and as dumping grounds for other troublemakers. As mentioned above, Massachusetts was settled by Puritans who had rejected the Church of England. Ironically, these seekers of religious freedom were so strict and dogmatic that anyone who disagreed even slightly was unwelcome in their new “city upon a hill”. Advocates of further reform soon left and settled Connecticut and Rhode Island, which were open to settlers of all religions—except Catholics who instead settled in Maryland. Another dissenting religious group from England, the Quakers, colonized Pennsylvania, while Georgia was partly settled by petty criminals “transported” from Great Britain (Australia would serve this role in the late 18th and early 19th century). As a result, settlers of the Thirteen Colonies were less loyal to the British Crown than the Spanish settlers of Central and South America were to their monarch. Indeed, if the Spanish had followed the British policy of shipping their undesirables to the New World, “Latin” America might have become “Judeo-Islamic” America, a place where Jews and Muslims who had refused to convert to Catholicism were sent.

The Spanish and British also governed their colonies in very different ways. The Spanish Crown wanted to directly rule their American empire, appointing trusted men—the peninsulares—to serve as viceroys, judges, governors, and mayors, applying laws and regulations made by the Council of the Indies in Spain. British colonists had already had already a sense of self-government through their parliament, which checked the power of the King and controlled the treasury. Subsequently, in contrast to Spanish settlers, the British colonists set up legislatures, held town-hall meetings, often appointed their own governors, and made many of their own laws rather than waiting for instructions from London.

This difference in representative government, however, does not mean that the Spanish colonists were completely deferential. They often applied the concept of “obedezco, pero no cumplo” (“I obey, but I do not comply”) to regulations made by the Council of Indies that they believed did not consider local realities in the Americas. Also, especially in the 1700s, artisans and laborers initiated local riots and uprisings against unjust taxes or changes in religious governance, where the crowds shouted “Long live the king, and death to bad government!” until the wrongs were righted. Similar protests in the Thirteen Colonies would not occur until the 1770s.

Land arrangements were also very different between the British and the Spanish. Both empires had sugar and other plantations which depended on enslaved African labor (which we will examine below). However, for other crops (especially those for local consumption), the Spanish followed the tradition of the encomendero (and, later, hacendero), in which a large landowner employed indigenous and mestizo workers, while the British settlers preferred the individual family farm. In the long run, this economic difference affected attitudes about entrepreneurship and ideas of personal liberty. The large landowners in Spanish America did not want to disrupt a social system which brought them wealth, while in the Thirteen Colonies, even the lowliest indentured servant who had worked without pay for seven years, looked forward to gaining their own plot for themselves “out West.”

The fourth major difference between Spanish and British America involves relationships with the indigenous peoples. Basically, the Spanish had arrived and said, “This is our land, obey us” while the British said, “This is our land, go somewhere else.” The Spanish Empire included the indigenous in their colonial project, partly because of the blood ties that connected many of the Spanish with their mestizo descendants. Mestizos and Indians were often protected or at least tolerated by Spanish authorities in their own settlements as long as they paid tribute and at least pretended to be Catholic. Just like their counterparts in North America, the Indians in Latin America also faced the problem of the Spanish allowing their pigs and cattle to destroy native plantings—but as Spanish colonial records reveal, the indigenous brought this injustice to local Spanish judges, who often determined in favor of the Indians. Many natives felt part of colonial society, and confidently challenged Spanish landowners in court.

Still, the Spanish colonies were far from a utopia for the natives. They did not have complete control over their lives and the “protection” offered by Catholic clergy required abandoning their own religion and many of their customs and practices. The Spanish did not want to physically eliminate the indigenous, but they did advocate a cultural genocide of sorts, which was never complete due to native resistance. But this was, in the long run, less successful than the destruction of native culture in North America because despite the Columbian Exchange there were more natives left. Native languages thrive in many parts of Central and South America where they are preserved and spoken by millions, while the tribal tongues of North America struggle to stay relevant.

The social and economic differences between British and Spanish America clearly have consequences even today, some positive and others negative. The entrepreneurial spirit common in the United States has resulted in a less rigid class system than in Latin America, while the idea that the U.S. is a “white man’s country” (in which African-Americans were also excluded) has led to systemic racism which is still an enormous problem, especially when compared to attitudes about race in most of Latin America, where mestizos and mulattos abound.

Caribbean Islands and Sugar Cane

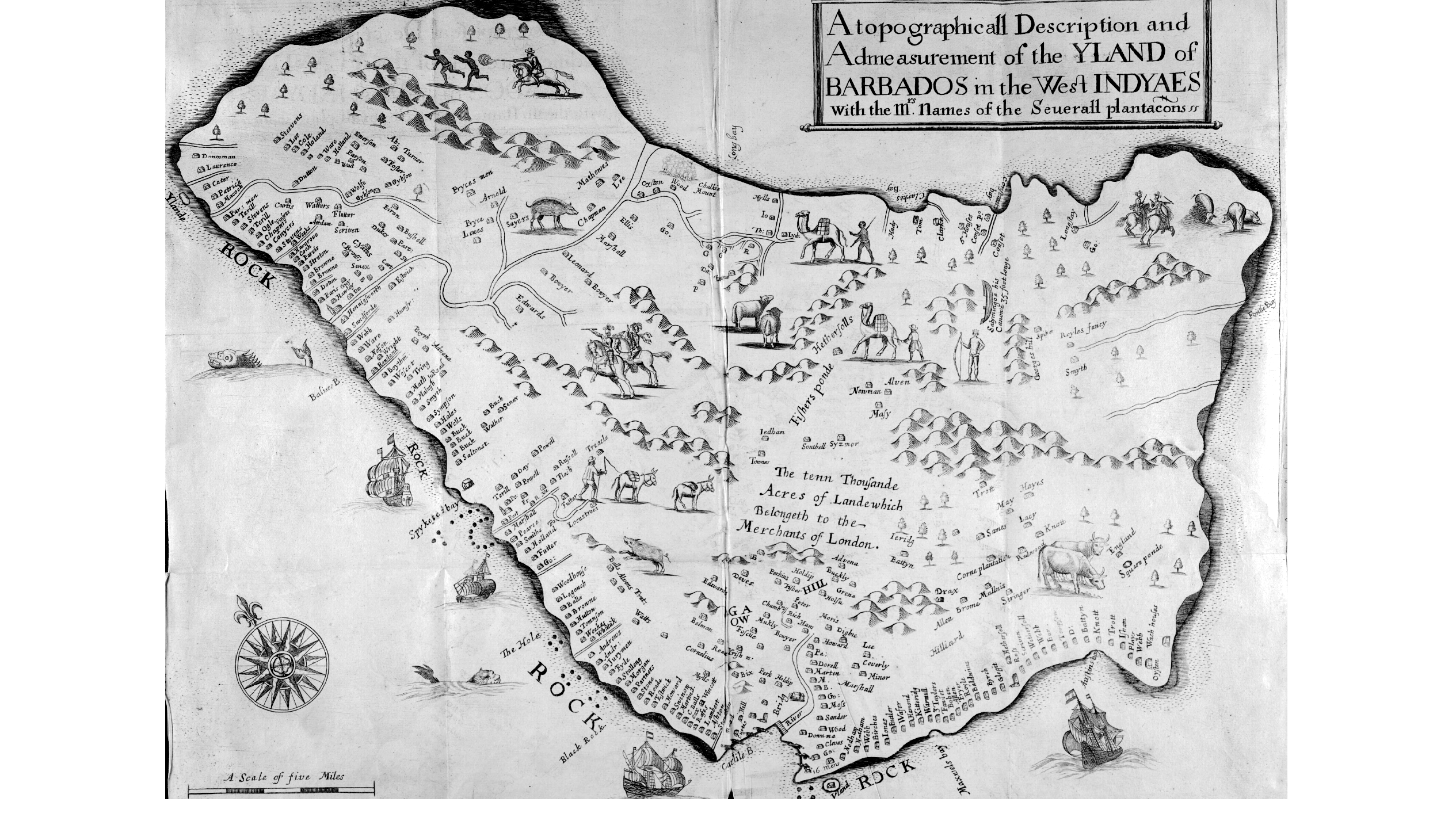

In spite of the beginning of British settlement in North America, Britain’s main focus in the 17th century was the Caribbean. We tend to forget this, because this region did not join the North American revolution in 1776 and become part of the United States. But in the 1600s, Sugar Islands like Barbados and Jamaica were the most profitable British colonies. Like the Spanish, North American colonists in the New World expected and hoped to find not only a place to build a new society, but also a place where they could get rich. Even religious idealists such as the Pilgrims looked forward to opportunities for wealth and social mobility that had not been available to them in England. And right from the start, European colonies in North America were commercial. In addition to fishing, growing tobacco, and trapping beaver, the North American colonies benefited from the booming sugar economy of the Caribbean.

Islands such as Barbados that had once been self-sufficient had begun by the mid-1600s to specialize in the profitable commodity at the expense of all other crops, so sugar planters looked to their neighbor colonies for food supplies and feed for draft animals. John Winthrop, the Puritan leader who helped establish Boston and who was Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony four times before 1650, sent his second son Henry to help establish Barbados in 1626. When Oliver Cromwell’s Civil War halted the flow of commercial shipping between England and the ten-year-old Bay Colony in 1640, trade with the West Indies saved Boston’s economy. Governor Winthrop’s younger son Samuel joined the growing community of New England merchants in the Caribbean sugar islands in 1647.

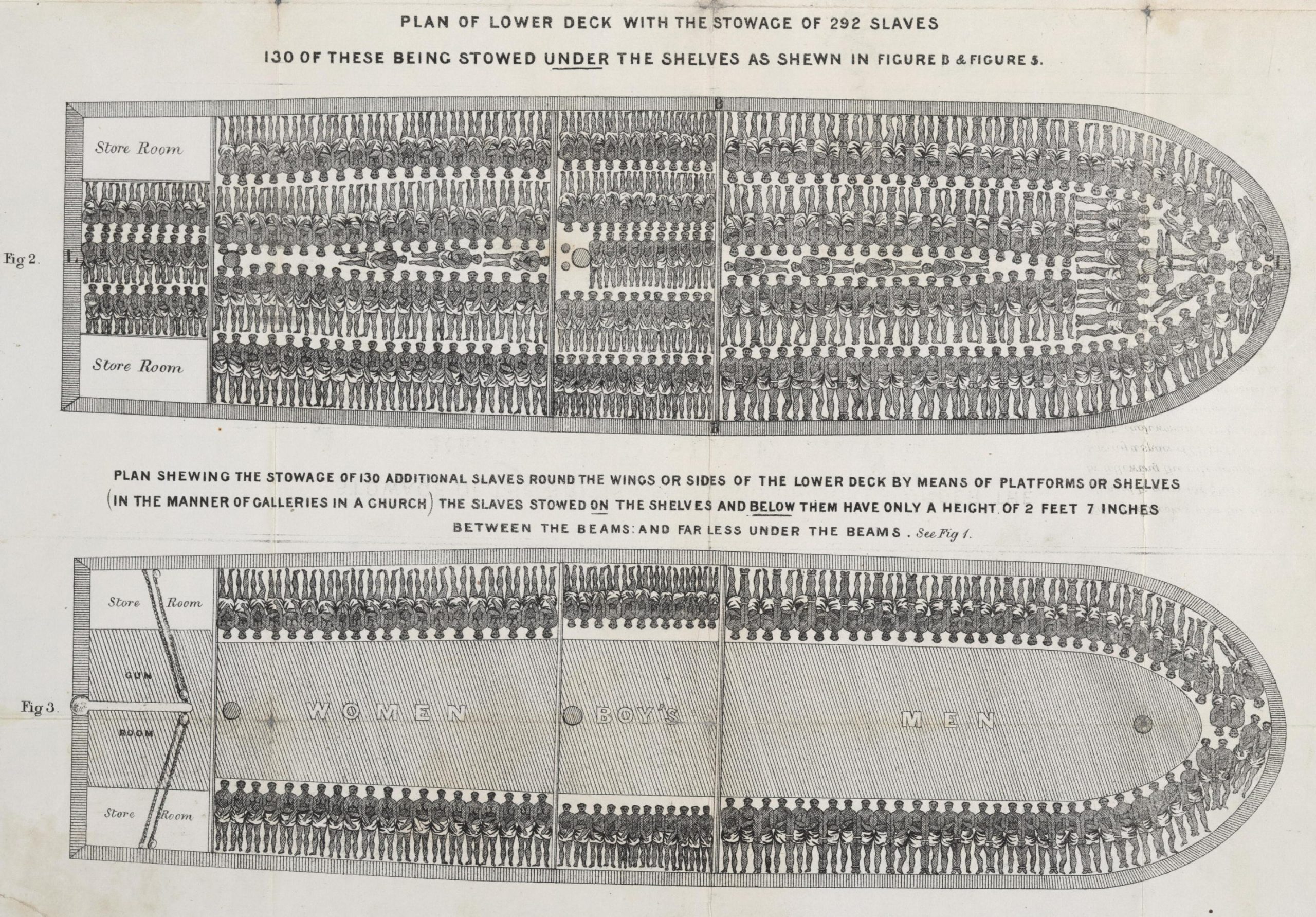

About 16 million Africans were captured and transported to European slaveholding colonies during the entire period of Atlantic slavery. Only 12 million arrived alive. A quarter of all slaves taken died on the voyage across the Atlantic. Although slavery reduced African population by over 26 million (10 million to the Islamic world and 16 million to the Atlantic), American staples including corn and manioc created a population boom that exceeded the losses to the slave trade. However, if these 26 million people had been available to contribute to African society, what social and cultural progress might have been possible? Additionally, since African nations–like other societies–tended to enslave captives in war, conflicts among tribes and kingdoms created an unstable social and political climate, which made sub-Saharan Africa ripe for European imperialists in the late nineteenth century, well after the slave trade with the Americas had ended.

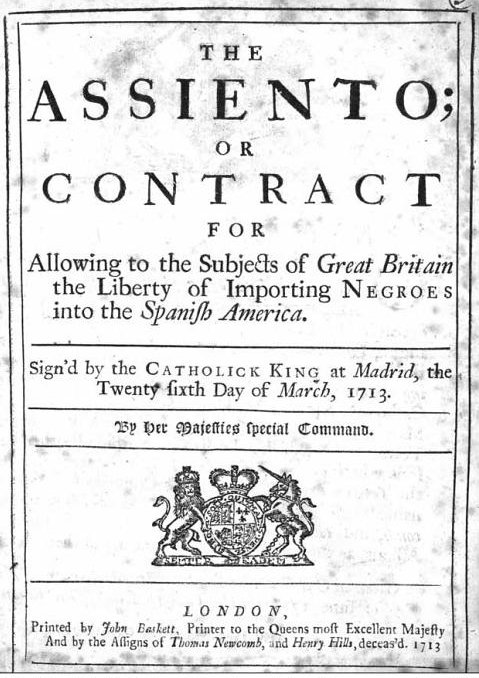

Under the Treaty of Tordesillas, Spain was not allowed to purchase slaves in Africa because it was part of the territory granted to Portugal. So Spain had set up a monopoly contract for slave trading to Spanish America called the Asiento, which was initially granted to France. In 1714, Spain shifted the Asiento to Britain and gave the South Sea Company a 30-year monopoly on selling slaves to Spain. The Company set up slave distribution “factories” at Cartagena (Colombia), Veracruz (Mexico), Portobello (Panama), La Guaira (Venezuela), Buenos Aires (Argentina), Havana, and Santiago de Cuba, as well as its own colonies of Barbados and Jamaica. In 1720, a speculative investment “bubble” burst, throwing the British economy into crisis. The South Sea Company survived the burst of its bubble, mostly due to revenues from selling slaves, and its slave sales peaked in 1725, five years after the financial crisis.

Conditions were so harsh on sugar plantations that slaves generally died after about three years after their arrival. Plantation owners could have changed their practices, but the reduced profits would have exceeded the replacement costs of the slaves, so planters chose to work slaves to death quickly and buy more. The economic value of local “increase” produced by enslaved women was recognized in the 18th century in the North American colonies where people like Thomas Jefferson wrote about the money that could be made on these natural replacements. Additionally, raising tobacco and other crops was less harsh than cultivating sugar cane, creating better conditions for survival. Britain and the U.S. ended the slave trade in 1807 and 1808 but slavery continued in the U.S., where enslaved people in Mid-Atlantic states where tobacco was being replaced with mechanized wheat-farming were “sold down the river” to the increasingly important cotton plantations in the Deep South, creating a major profit opportunity for white Virginians.

Slaves often resisted their captors. Sometimes they ran away and formed independent communities in remote hinterlands called Maroon colonies. Many of these Maroon colonies became stable societies, populated by escaped slaves and the descendants of Indians who had run away from the colonists’ earlier attempts to enslave them and some even lasted into the twentieth century in Central and South America.

Other times, the slaves rebelled – usually unsuccessfully, but not always. Traditional histories sometimes seem to not give enough attention to slave resistance, but here’s a partial list of some notable revolts (there were a dozen more in the 19th century):

- 1526 San Miguel de Gualdape (Spanish Florida, Victorious)

- 1570 Gaspar Yanga‘s Revolt (Veracruz, New Spain, Victorious)

- 1712 New York Slave Revolt (British Province of New York, Suppressed)

- 1730 First Maroon War (British Jamaica, Victorious)

- 1733 St. John Slave Revolt (Danish Saint John, Suppressed)

- 1739 Stono Rebellion (British Province of South Carolina, Suppressed)

- 1741 New York Conspiracy (Province of New York, Suppressed)

- 1760 Tacky’s War (British Jamaica, Suppressed)

- 1787 Abaco Slave Revolt (British Bahamas, Suppressed)

- 1791 Mina Conspiracy (Louisiana (New Spain), Suppressed)

- 1795 Pointe Coupée Conspiracy (Louisiana (New Spain), Suppressed)

- 1791–1804 Haitian Revolution (French Saint-Domingue, Victorious

The French and haitian RevolutionS

Debt problems stemming from the Seven Years War and French support for the independence of the United States forced King Louis XVI to call the Estates-General in 1789, in order to raise revenue. The Estates-General had not been called since 1614, and its meeting was immediately seen as an opportunity to create a new parliamentary monarchy.

The three “estates”, commoners, nobility, and clergy, traditionally all had the same power; but it was not much compared to the absolute monarch. In 1789, the commoners were dominated by educated merchants and large landowners who advocated for establishing a British-style parliament as a check on the King’s power. The commoners had enough support from sectors of the clergy and nobility to declare themselves as the National Assembly, which set about forming a new government.

Dissatisfaction with the current government and excitement over establishing a new one inspired the people of Paris to form militia groups to defend the National Assembly from royalist attacks. On July 14th, these militias dramatically took over the Bastille, a royal prison which held political dissidents. In August the National Assembly agreed to a Declaration of the Rights of Man which claimed “Natural Law” as the basis for equal rights for all and called for liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. Like the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Constitution, the Assembly declared the the “nation” was sovereign, rather than the king, and asserted the rights of freedom of speech, the press, religion, and assembly.

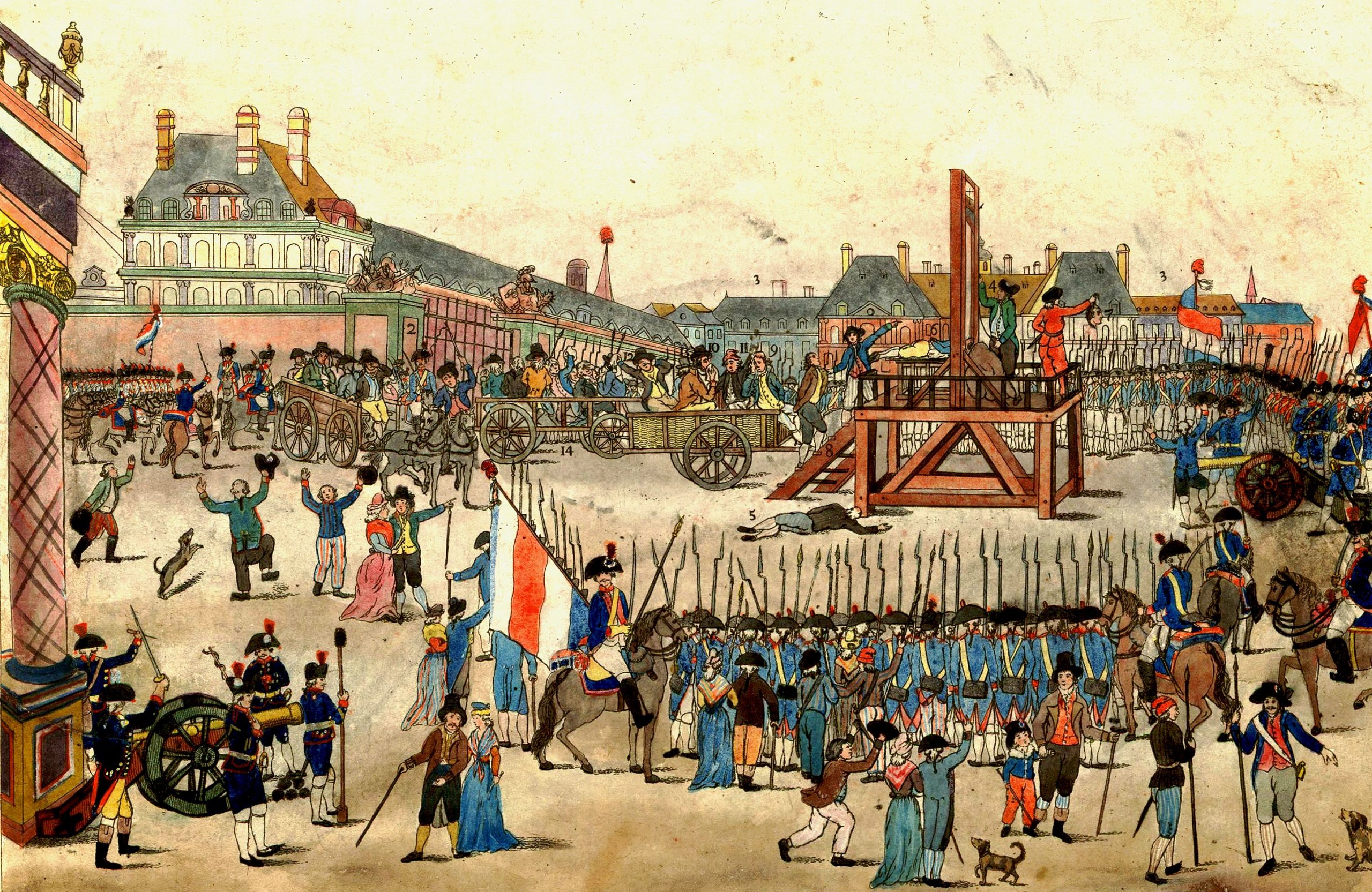

However, the French Revolution differed from the American in that it was not a colonial independence movement, but a rejection of an existing monarchy by the people of France. There was a much greater degree of participation by poor people in France in this process, and the social changes attempted by the new government were much more significant than simply replacing a British ruling class with an American one as the revolution had done in the new United States. Unfortunately, the power vacuum created by the complete elimination of the prior government structure resulted in the rise of a radical Jacobin Party led by Maximillian Robespierre. By 1793, a Reign of Terror imprisoned 300,000 people and executed 40,000, including King Louis XVI and his Queen, Marie Antoinette.

The Reign of Terror led to a rejection of the Jacobin party and the trial and execution of Robespierre in 1794. A more conservative government, the Directory, was installed but it failed to manage an orderly transition from the old regime to a new style of republican government. The Directory’s failure created an opening for an ambitious opportunist named Napoleon Bonaparte, who as a general of the French Army had defended the Directory and the new French Republic against the neighboring monarchies, which had sent in troops to put down the Revolution. Returning from an Egyptian campaign in 1799, Napoleon overthrew the Directory and like Julius Caesar established a 3-man Consul style government—but unlike Caesar he quickly became the sole leader. Napoleon crowned himself Emperor in 1802.

In a series of wars between 1804 and 1807, Napoleon extended French control to much of Germany, Italy, Spain, and the duchy of Warsaw, and built strong alliances with Austria and Prussia. At its height, the French Empire ruled over 70 million subjects, and to secure its most profitable colony Napoleon sent 40,000 troops across the Atlantic to Hispaniola to try to retake San Dominique from an army of rebellious former slaves led by Toussaint l’Ouverture, one of the most important leaders of the revolutionary age.

Encouraged by the French Revolution, slaves on sugar plantations on Hispaniola, which the French had renamed San Dominique, rebelled in 1791 and overthrew the white government of the island. Slavery in French colonies was then abolished by the Jacobins in 1793 (one of the few things Robespierre got right) and the army of former slaves fought a British invasion to a standstill in a 5-year war ending in 1798. But after declaring himself Emperor of the French, Napoleon reinstituted slavery and sent troops to retake the island for France.

Napoleon’s army, which outnumbered Haitian forces two to one, captured l’Ouverture in 1803 and transported him to a French prison where he died, but the revolution continued under l’Overture’s lieutenant Jean-Jacques Dessalines. The former slaves defeated the French and established the Republic of Haiti in 1804. Although the Declaration of Independence’s author Thomas Jefferson was President when Haiti became the first ever nation created by former slaves who gained their freedom in armed rebellion and only the second American republic to free itself from European colonialism, the author of the Declaration refused to recognize Haiti’s independence. The slavery-supporting South actually blocked recognition of Haiti by the U.S. government until the Civil War, when a North-only Congress and President Lincoln finally established diplomatic relations in 1862.

Revolution and Nationalism are related, but the relationship is complicated. In the case of the United States and Haiti, revolution led to the creation of new nations. In France, revolution led to chaos and Napoleon’s attempt at empire-building. Napoleon’s empire might have lasted a bit longer, if he had not been so interested in expanding it to include not only Europe and Haiti, but Russia. In a final example of bad judgment, Napoleon invaded Russia and occupied Moscow in September 1812. Russia’s fast-moving Cossack cavalry executed a scorched-earth retreat before the advancing French army, so Napoleon’s forces arrived in Moscow hungry, only to find that the city’s quarter-million people had abandoned their homes and taken everything they could carry. The French burned the city (possibly by accident) and began a long retreat in early October at the beginning of what turned out to be a brutal winter. To make matters worse, Russian cavalry repeatedly cut the French supply lines, and of an original force of over 600,000 men, only about 100,000 made it back to France alive. Napoleon was able to build the army back up again, although replacing the horses the troops had eaten during the retreat was harder. But this crushing debacle proved to the world he wasn’t the military genius many had believed him to be.

Napoleon’s enemies invaded France in 1814, forced him to abdicate, and exiled him to Elba, a small island near his boyhood home of Corsica. Napoleon escaped the Mediterranean island and regained power briefly in 1815 before being defeated at Waterloo and exiled to St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where he died six years later at the age of 51.

Independence of Latin America

Napoleon’s conquest of Europe inadvertently created the conditions for additional revolutions and the creation of new nations in the Americas. As described in the last chapter, Spanish American society was based on a small aristocracy of ethnic Spanish peninsulares (people born on the Iberian peninsula) and creoles (people of Spanish descent born in the colonies) ruling large populations of mestizo (mixed) populations, Indians, and slaves. Like the leaders of the American Revolution, many of these colonial aristocrats felt the priorities of their rulers in Spain did not match their own. Napoleon’s removal of the hereditary king and installation of his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne in 1807 removed the last shred of doubt. Soon after Joseph Bonaparte took the throne, representative juntas were established in Caracas, Santiago, Buenos Aires, and Bogota to rule in the name of the deposed Spanish king.

In 1810 a creole priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla began Mexico’s revolutionary movement, by giving a speech known as the “Grito de Dolores” or simply El Grito, the Cry. Hidalgo raised an army of 100,000 men, largely of landless peasants anxious for social reform, but they were defeated in January 1811 by a professional army of about 6,000 Spanish troops. Hidalgo was convicted of treason against Spain and executed. Another (this time mestizo) priest named José Maria Morelos took over the insurrection and convened a Congress in 1813 that wrote a constitution for Mexico called the Decreto Constitucional para la Libertad de la America Mexica which declared Mexico’s independence. Unlike later independence movements in South America, Mexico’s demanded not just political but also social change.

In 1815 Morelos was also captured and executed. His lieutenant Vicente Guerrero continued the war for independence. Guerrero would be elected president of Mexico in 1829 and would be Mexico’s first black president. But it was a long way to 1829.

King Ferdinand VII was the Spanish monarch who had been forced to abdicate in 1808 in favor of Joseph Bonaparte. He regained the throne in 1813, but quickly became known as el Rey Felón, the criminal king. Ferdinand rejected the liberal 1812 Constitution that had been adopted by Spain’s rebel government during his absence. Historians have described him as “the basest king in Spanish history. Cowardly, selfish, grasping, suspicious, and vengeful, [he] seemed almost incapable of any perception of the commonwealth. He thought only in terms of his power and security and was unmoved by the enormous sacrifices of Spanish people to retain their independence and preserve his throne.” Latin American juntas and the Mexican rebels decided he did not deserve their allegiance and began fighting for their independence from Spain.

The royal government sent a general named Agustín de Iturbide against Guerrero’s forces in Mexico, but Guerrero beat Iturbide on the battlefield and then convinced him to join the revolution. In 1821 the two allied under the Plan de Iguala, or the “Plan of the Three Guarantees,” which proclaimed Mexico’s independence and declared that “All inhabitants . . . without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens . . . with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues.” When Iturbide declared himself emperor of Mexico, Guerrero and his supporters rebelled and although Iturbide defeated them in the field he resigned when Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna also rebelled, and went into exile. Mexican history is very complicated and turbulent: suffice it to say that both Iturbide and Guerrero ended up being executed in their turns.

In 1811 Venezuela and Paraguay both declared their independence from Spain. In 1816 Argentina declared its independence, followed quickly by Chile and Gran Colombia. King Pedro of Portugal, whose father had fled to Brazil in 1807 to avoid being deposed by Napoleon, declared Brazil a constitutional empire under his rule in 1822. In 1824, the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar, who had led the liberation of Gran Colombia, conclusively defeated the Spanish armies at Junín and Sucre, and Peru gained its independence. A year later the eastern portion of the old viceroyalty of Peru became a separate country named after the liberator Bolívar: Bolivia.

Gran Colombia was a republic that includes territory now part of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil. Bolívar was elected President of Gran Colombia from 1819 to 1830. He hoped Latin America would follow the example of the United States and create a federal union of all the newly-independent nations—or at least a common economic market. He convened a Congress of the Americas in the summer of 1826, inviting all the nations of Latin America and also the United States. The U.S. President, John Quincy Adams, didn’t have a very high opinion of Latin Americans but he was an opponent of slavery and all of the new Spanish America republics had immediately outlawed the slave trade and had either abolished slavery or had initiated its gradual disappearance through manumission. (The independent Brazilian Empire, on the other hand, did not formally end enslavement of people of color until 1888, the last nation in the Americas to do so). Adams had been instrumental in promulgating the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, establishing the Western Hemisphere as a region under the protection of the US and warning European nations, especially Great Britain, to limit their activities in the Americas.

Britain, however, did attend the Congress of the Americas as an observer and managed to gain several important trade deals as a result. But blocked once again by the slaveholding South, the U.S. government dragged its feet. Although the U.S. ultimately decided to send a delegation, it arrived only after the Congress had ended. Bolívar was unable to establish the Pan-American commonwealth he had dreamed of or even hold Gran Colombia together. He resigned the presidency in the spring of 1830 and the republic dissolved into political chaos and the three separate nations of Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador. Bolívar died of tuberculosis at age 47 later that year.

Media Attributions

- 4863003

- Mapstaug

- The_Trapper’s_Bride

- Cotton_Mather

- Philip_King_of_Mount_Hope_by_Paul_Revere

- Spanish_America_XVIII_Century_(Most_Expansion)

- Mestiso_1770

- download

- Uncle_sam_propaganda_in_ww1

- 1713_Asiento_contract

- The_Mill_Yard_-_Ten_Views_in_the_Island_of_Antigua_(1823),_plate_V_-_BL

- Battle_for_Palm_Tree_Hill

- Omaha_courthouse_lynching

- Night_Bivouac_of_Great_Army