6 New Imperialism

The 19th century and the turn of the 20th century are often described as a period when the power of many land-based empires diminished and nationalism became the most important organizing principle for societies around the world. Actually, powerful nations in Europe and America pursued overseas empires and expanded into Africa and East Asia, until a wave of “decolonization” after World War Two. And even then, “empires” have remained as important as ever in the late 20th and the 21st century, although the power of the new empires that have been successful has been largely economic rather than political.

Consider the decline of the empires we’ve already become familiar with in earlier chapters, in Asia, Europe, and the Muslim world. They were territorial empires that had used military conquest to impose political control over wide expanses of land adjacent to their ancestral homelands. They existed by providing a degree of civil and economic order, in exchange for taxes on the agricultural produce of the agrarian populations they conquered. These empires usually left their citizens more or less alone to speak their own languages, practice their own religions, and observe their own cultural traditions. Occasionally they took captives from conquered lands, like the janissaries of the Ottoman Empire.

The Portuguese and Spanish began establishing the first European overseas empires in Azores and Canary Islands in the late 1400s, extending their overseas imperial project into the Americas after 1492. In the process, the Spanish defeated several land-based indigenous empires such as the Aztecs, Inca, and Maya, and replaced the native rulers with Spanish Viceroys. The British, French, Dutch, and others soon followed the Iberians into the Caribbean and North America. All the European colonies in the Americas were controlled by their respective “mother” countries, sending resources like silver and gold and agricultural products (especially sugar) to Europe, and often required to trade only with the “mother” economy. As we will see, Europeans continued this model of overseas empires in the 1800s as Africa and parts of Asia came to be dominated by outside imperial powers.

The Portuguese and Spanish began establishing the first European overseas empires in Azores and Canary Islands in the late 1400s, extending their overseas imperial project into the Americas after 1492. In the process, the Spanish defeated several land-based indigenous empires such as the Aztecs, Inca, and Maya, and replaced the native rulers with Spanish Viceroys. The British, French, Dutch, and others soon followed the Iberians into the Caribbean and North America. All the European colonies in the Americas were controlled by their respective “mother” countries, sending resources like silver and gold and agricultural products (especially sugar) to Europe, and often required to trade only with the “mother” economy. As we will see, Europeans continued this model of overseas empires in the 1800s as Africa and parts of Asia came to be dominated by outside imperial powers.

However, the new project of economic “neo-imperialism” also appeared in the 19th century, especially in the new republics of Latin America. In this case, supposedly independent countries that had recently won their independence from the Spanish and Portuguese empires, were economically dominated by European and U.S. investors, still providing raw materials for the “Great Powers” in exchange for finished industrial goods. As presented later, nearly all of these new nations became indebted to European banks and faced the humiliation of “gunboat diplomacy” in which U.S. and European powers took over custom houses to force payment of loans.

Before World War One, the decline of land-based empires was nearly complete, while overseas empires flourished.

Declining Land-Based Empires

The land-based empires began a precipitous decline after the Napoleonic wars, some sooner than others. The challenge of nationalism some of these multi-ethnic empires. Members of distinct cultural, religious, and linguistic groups began to demand more autonomy within these empires, which frequently led to the establishment of independent nation-states. In other cases, empires that resisted change were conquered by powerful nations expanding their overseas empires. Often these factors combined to challenge land-based empires.

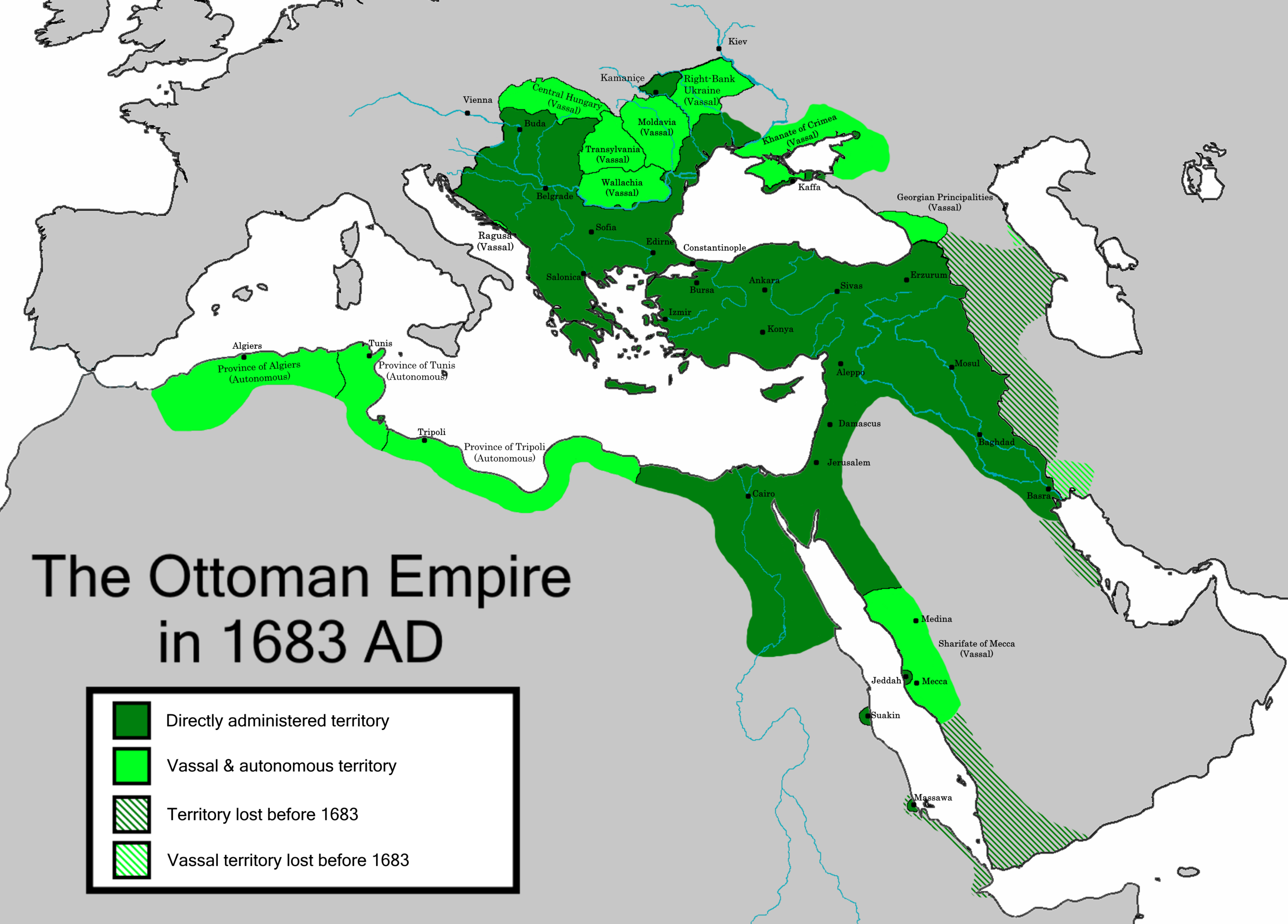

The Ottoman Empire declined very slowly during the 19th century—when it was called “the Sick Man of Europe”—but it was able to persist until World War I. The Sunni Muslim Ottoman homeland was present-day Turkey, which bordered on Orthodox Christian Russia to the north, the Catholic Habsburg (Austro-Hungarian) Empire to the west, and the Shiite Iranians who succeeded the Safavid Empire in Persia to the east. The Russians aided the Orthodox Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgarians in their successful struggles for independence. The Ottoman capital, Istanbul, had been Constantinople, home of the Byzantine Empire and of Greek Orthodox Christianity before the Ottoman conquest of 1453; and the leaders of Russia wanted to reestablish Christian rule there.

The Ottoman Empire declined very slowly during the 19th century—when it was called “the Sick Man of Europe”—but it was able to persist until World War I. The Sunni Muslim Ottoman homeland was present-day Turkey, which bordered on Orthodox Christian Russia to the north, the Catholic Habsburg (Austro-Hungarian) Empire to the west, and the Shiite Iranians who succeeded the Safavid Empire in Persia to the east. The Russians aided the Orthodox Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgarians in their successful struggles for independence. The Ottoman capital, Istanbul, had been Constantinople, home of the Byzantine Empire and of Greek Orthodox Christianity before the Ottoman conquest of 1453; and the leaders of Russia wanted to reestablish Christian rule there.

The Greeks were the first to successfully free themselves from Ottoman rule in the 1820s. They found support not only from Imperial Russia, but also from the British and French, who sought more economic and political influence in the Eastern Mediterranean. The struggle for Greek freedom, in the birthplace of democracy and and home of classical literature and art, fired the imagination of the artists and writers of the “Romantic” movement then flourishing in Europe. English poet Lord Byron lost his life in service to the Greek cause.

By the mid-19th century, disputes between European powers over what would happen to Ottoman territory caused the Crimean War (1853-1856), in which France, Great Britain, the Italian Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Ottomans opposed an expanding Russian Empire. The Crimean War was the first major war of the Industrial Age, featuring the use of railways, telegraphs, and modern ordnance like rifles and exploding naval artillery. Disastrous mismatches between traditional military tactics and the realities of modern war occurred, such as the incident immortalized in Alfred Tennyson’s poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” The poem describes a frontal assault by a British light cavalry unit armed only with lances and sabers against an artillery battery dug in on high ground at the battle of Balaclava in 1855. Although Tennyson’s poem praises the bravery of the cavalrymen who charged through the so-called Valley of Death, events like these became symbols of the logistical and tactical mismanagement of the war effort. The conflict also revealed the weakness of the Russian Empire, which fielded large armies but lagged in both tactics and technology. In the treaty following the war, Russia was forced to remove its naval fleet from the Black Sea.

The Ottomans also faced an ongoing dispute with the Egyptians, who gained practical independence under the Ottoman-appointed governor Muhammad Ali from 1805-1848. Ali modernized Egypt in many ways, while his son, Muhammad Sa’id, granted a land concession in 1854 to French businessman Ferdinand de Lesseps to dig a canal from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. The building of the Suez Canal, completed in 1869, was initially opposed by Great Britain because they feared its control by the French would shift the balance of power in Europe. The canal took eleven years to build, using forced Egyptian labor. Although the Suez Canal Company was an international corporation, its shares did not sell well outside France and Egypt. But in 1875, Sa’id’s son Ismail put Egypt’s shares up for sale and British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli bought the shares with an unsecured £4,000,000 loan from his close personal friend Baron Lionel de Rothschild, head of the famous international bank. Although France still owned more shares, Britain sent troops to protect the canal during an Egyptian civil war in 1882 and in 1888 the canal was declared a neutral zone under British protection. Using the canal, British steamships were able to avoid sailing around Africa and reach India in two weeks instead of two months.

Inspired by the example of the Greeks, and encouraged by the Russians and others, Montenegro, Serbia, and Bulgaria achieved nearly-complete independence from the Sultan in Istanbul by 1878. Although they belonged to distinct ethnic and linguistic groups, the majority of people in these territories were Orthodox Christians. However, as we will see in the next chapter, these new countries had trouble resolving disputes over borders and political control, since the different peoples lived all over the region in villages and towns that were frequently “majority-minority.” Nationalism was the motivation for independence, but the national community existed across many frontiers—how should they be united? And what should be done about the “other” living within one’s own country?

When the Russian Empire’s ambitions were thwarted in the Crimean War, Russians were forced to confront their military incompetence and social backwardness. Serfdom tied peasants and their families to the land, and although they were not slaves, serfs were included in any property transaction among the landed gentry. Tsar Alexander II declared an end to serfdom in 1861, shortly before President Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, during the United States Civil War. Both countries were among the last in their respective regions to formally end forced labor obligations and like the newly-“freed” in the U.S., the liberty of many former Russian serfs existed only on paper.

Russian industries expanded with investment from western Europe: factories and rail networks soon appeared, especially in the European part of Russia. However, the slowness of political and social change led to frustration among potential reformers, who instead turned to revolutionary action, often led by anarchists. Anarchism is similar to socialism in its concept of class struggle, but anarchists believe that all forms of top-down control—governments, police, organized religion—should be immediately eliminated, allowing the natural cooperativeness of humanity to thrive in smaller consensus-based entities. Russian anarchists succeeded in assassinating the reformist Tsar Alexander II in 1881, on the day he had given approval for a limited form of parliamentary government. His son, Alexander III, rejected this political reform; he, in turn, was also murdered by anarchists, in 1894. His son, Nicholas II, was not open to any checks on his absolute power.

Dozens of ethnic and religious groups lived in the territories of the Russian Empire; attempts at “russification” were inconclusive. The Poles, Finns, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, and Romanians, among many others, chafed under the autocratic rule of the Tsars, and desired independence—or simply immigrated to the U.S. for better economic opportunities. Jewish Russians, many of whom lived in territory taken from Poland in the 1790s, were blamed for misfortunes like the deaths of babies or cattle and attacked in violent “pogroms”. Jews from these Russia and Eastern Europe also often chose a new life in the United States rather than discrimination and persecution. Later pogroms, such as one in Odessa in 1905 in which hundreds of Jews lost their lives, received international condemnation and were presented as proof of Tsarist Russia’s backwardness.

In the late 19th century, the Tsarist autocracy encouraged anti-Semitism: the idea that Jews were the cause of political, economic, and social problems, and needed to be controlled and occasionally “put in their place” in violent pogroms. Although Jews had lived in the region for centuries, they were always considered an “other” and the Tsars restricted their ability to own land and to exercise certain professions. Local and national leaders blamed the Jews for every assassination and economic downturn in order to unite opposition groups with the goals of the Tsars. Attacks on Jewish communities and neighborhoods—pogroms—occurred with frightening frequency from the 1880s until the eve of World War One. Jews from these territories often chose immigration to the United States to flee discrimination and persecution, while later pogroms, such as the one in Odessa in 1905 in which hundreds of Jews lost their lives, received international condemnation and were presented as proof of Tsarist Russia’s backwardness.

Growth of the Habsburg Empire from the red and pink center outward to the yellow and green conquests of the 18th and 19th centuries.The Habsburg dynasty had ruled Austria and its territories since the late 1200s; through strategic marriages, the family also controlled the Spanish Empire in the 1500s and 1600s, including the Spanish-American colonies. The Spanish line died out in 1700, but the Austrian House of Habsburg would reign until 1918.

At the end of the Napoleonic period, the Habsburg Empire dominated southeastern Europe, up to the frontiers of the Ottoman and Russians. While the Tsars felt a special kinship with Orthodox Christians under Turkish rule—Greeks, Serbs, and Bulgarians—the Habsburg monarchs supported Catholics of the Ottoman region, like the Croats. Until 1815, the Habsburgs had been the Holy Roman Emperors; during the Protestant Reformation, they fought to maintain Catholicism as the official religion of their realm.

Although united by religion, the Habsburg empire was divided by a growing sense of nationality. German-speaking Austrian Habsburg emperors ruled Hungarians, Czechs, Ukrainians, Poles, Slovaks, Romanians, Jews, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, and Albanians. By the middle of the nineteenth century, many of these peoples wanted their own nations. The rebellions and revolutions of 1848 came close to breaking up the Habsburg territories in a wave of nationalist and socialist fervor. The revolutionaries did not achieve all of their goals, but serfdom was abolished, several regions gained a greater degree of autonomy, and Emperor Ferdinand I abdicated in favor of his nephew Franz Josef.

Unification of Italy in the 1860s and and Germany in 1870 allowed the Hungarians, who became the most numerous minority within the realm, to achieve near-complete independence. In 1867, the emperor agreed to establish a “dual monarchy”, the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Administration was divided between Austrian and Hungarian parliaments, while the Austrian emperor managed foreign policy. This compromise merely spread out the nationalist problem for two kings instead of one: Romanians demanded more autonomy from the Hungarian administration in Budapest, while the Czechs asked for the same from the Austrian government in Vienna.

A united Germany, achieved in 1870, brought together an agricultural east with an industrialized west, creating an entirely new “Great Power” in Europe to rival Great Britain and France. The new nation called itself the German Empire (Deutsches Reich); its ambition to take a place at the table of imperial powers upset the post-Napoleonic European balance of power and, eventually, became a cause of the two twentieth-century world wars.

Otto von Bismarck, who had become prime minister of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1862, was the main architect of the German Empire. Although he was not among the young Germans who had dreamed of unification during the revolutions of 1848, Bismarck gradually came to the conclusion that to counter Austria-Hungary, which was over-extended in Italy and in its ambitions in the Balkans, Prussia had to take the initiative and gather the German states under the Prussian king. Bismarck used war as a way to unite the German principalities. First, in 1864, he started a brief war with Denmark that brought together most of the northern German states as allies of Prussia. A war with Austria in 1866 solidified these states in a confederation with Prussian King Wilhelm I, while at the same time, the newly unified Italy took advantage of a weakened Austria to claim Italian-speaking Hapsburg territories.

To bring in the mostly Catholic southern German states (led by Bavaria), Bismarck offended Napoleon III of France, making territorial promises in the Austrian war that he did not keep with the French emperor (among other transgressions). When the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, who had been president of France before declaring himself emperor, went to war with Prussia in 1870, he counted on the neutrality of the other German states and on Austrian help, neither of which happened.

Prussia had one of the best-trained armies in Europe and surprised the French with their rapid advance. Within weeks, they had captured Napoleon III himself. A leaderless France could not halt the united German advance and the capital, Paris, was taken over by a socialist-inspired Commune. The French agreed to territorial losses as they formed a Third Republic to replace Napoleon III. In early 1871, Bismarck initiated a gathering of the German princes at the French royal palace in Versailles, outside Paris, to join together as a new unified national state, with the Prussian King Wilhelm I as emperor.

A German empire created a new dynamic in diplomatic relations, based on French and German antagonism, forming new alliances and altering previous arrangements. The Franco-Prussian War was the first of three major conflicts between the French and the Germans over the next 75 years in which millions would die—but one can take heart in the idea that in more recent decades, the two countries have become strong allies, forming the primary economic and political relationship of the current European Union. If the French and Germans can set aside old conflicts and work together, perhaps Indians and Pakistanis, Sunnis and Shi’ites, Israelis and Palestinians, and other “enemies” can eventually do the same.

Rising Overseas Empires

Even though the British North American colonies achieved independence and became the United States, Britain held on to Canada and retained control of islands in the Caribbean, while (as described below) London’s bankers and British industry would dominate the finance and trade in the new Latin American republics.

Unlike the Thirteen Colonies, Canada achieved its independence from Britain much more slowly, without a revolution. Although the French-speaking Quebecois and the British in Ontario could easily have been at each other’s throats, anxiety over an invasion from the United States (which was tried unsuccessfully in 1775 and 1812) held a fragile alliance together. After two more incursions by American forces in the 1830s, the British North America Act of 1867 created the Dominion of Canada by combining Quebec, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and New Brunswick. John A. MacDonald became the nation’s first Prime Minister in 1867, negotiated the purchase of the Northwest Territories from the Hudson’s Bay company in 1869, and convinced Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, and British Columbia to join the Dominion. MacDonald knew that like the U.S., Canada’s eastern and western coastal regions needed a transcontinental railroad to bind them together. The Canadian Pacific Railroad was completed in 1885. The C.P. Railroad operates mostly just north of the border, although several lines connected to U.S. cities such as Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Detroit, and Chicago. Even today, 90% of Canada’s 36 million population live within 100 miles of the U.S. border.

The British had also claimed Australia, which they settled in the late 18th century with convicts. Most of the crimes were petty or related to debt, while some were political, such as the Irish condemned for protesting English rule. New Zealand was settled in the early 19th century through a private company, following the model established in the colonization of some of the Thirteen Colonies. In both cases, the native peoples lost land in much the same manner as in British North America. In Australia, the vast continent allowed for the aborigines to retreat, until environmental and other factors brought them into increasing contact with the settlers and their descendants. In New Zealand, relations between the native Maori and the settlers followed a pattern similar to those of the western United States: treaties made, treaties broken, wars fought and won by the settlers, who took more land. However, respect and celebration of Maori rights and culture have become integral to New Zealand identity in recent decades.

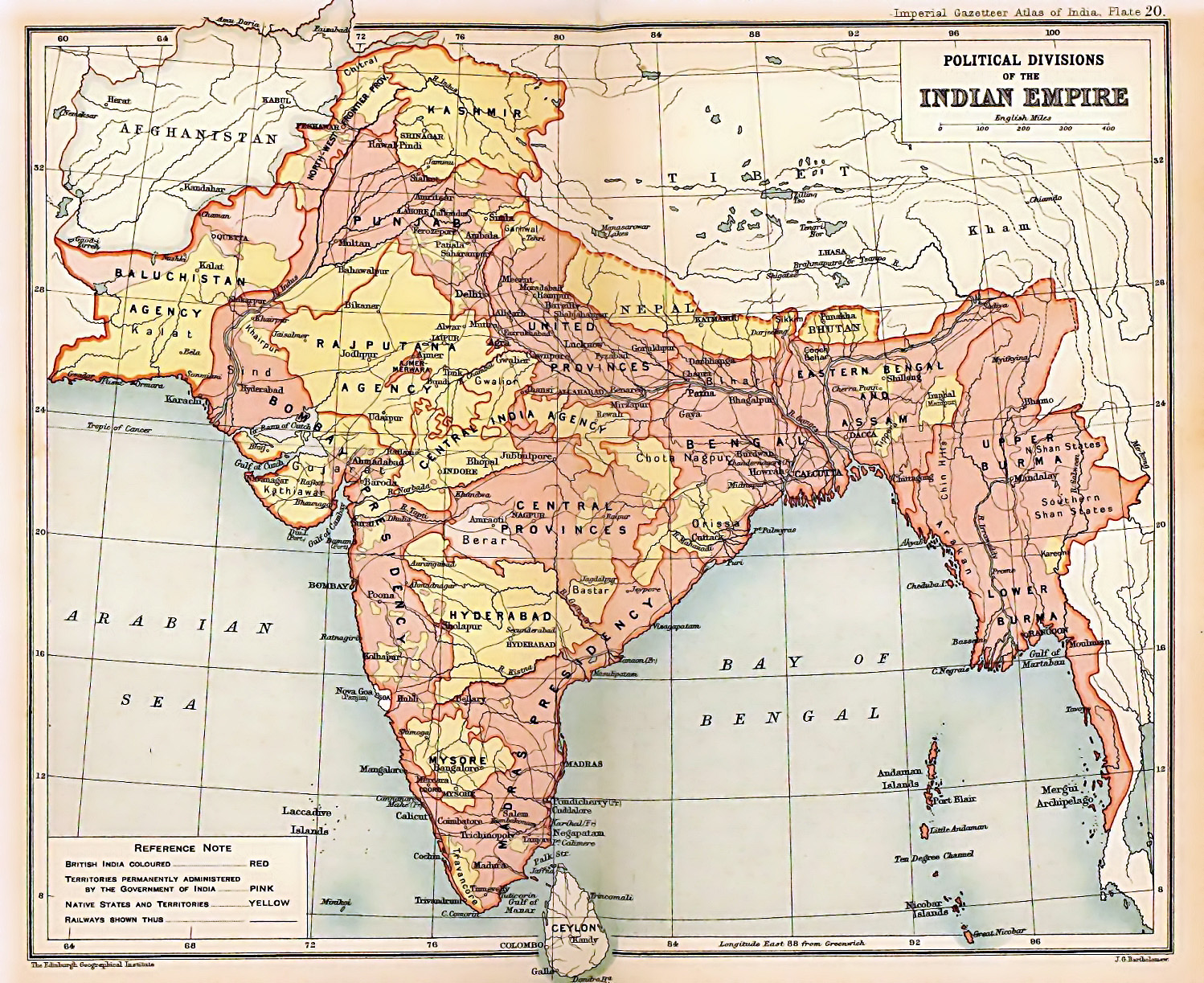

India was the most important colony for the British, determining much of its international diplomacy until after World War Two. When the British East India Company began its conquest of India in the 1700s, the Mughal Empire was entering a long period of decline after its peak in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Company took advantage of the empire’s weakness to expand its trading activities, and slowly took over the regional principalities that split off from Mughal control. By the 1700s, Indian tea had become an important part of the British diet—even for their colonists in North America, who dumped Indian tea into the Boston Harbor in protest against taxes on the product in 1773. By the middle of the 19th century, the Company controlled most of mainland India, Pakistan, Burma, and Bangladesh, as well as Sri Lanka. The Company shifted its policy away from simply trading, and began reorganizing the Indian economy, clearing forests and establishing widespread cultivation of tea, coffee, cotton, and opium for use in China. By the time the Crown took over direct control of the colony in 1858 after an uprising called the Sepoy Mutiny, India was a producer of agricultural products and raw materials for Britain’s growing industrial economy.

By the mid-19th century, the British in India had established an imperial model that had proved lucrative for investors: the colony provided raw material and resources for the consumers and industries of the “home country,” while Indians purchased mass-produced textiles and other goods from British factories as a “captive market.” This closed economic system was attractive to both older and newer European empires—setting off, as we shall see, a scramble for colonies in Africa in the late-19th century.

The British administration of India, however, also provided a model for other European imperialists. Clearly, the tiny island kingdom could not direct all of the affairs of their Indian possession—trained locals needed to aid in governance. This process began under the East India Company with the formation of native army and police forces, commanded by British officers, but soon included educated local administrators who spoke English and understood and applied imperial laws and edicts. By the 1850s, the British had founded their first schools to instruct the local elite in English, engineering, science, and British imperial law. This model proved so effective in India that Indian immigrants often followed the British to their new colonies in Africa, where Indians operated the railways and postal service, and Indian carpenters and bricklayers constructed government offices and private homes for the new colonial political and commercial elites. Indian shopkeepers played an enormous role in the local economies of these new colonies well into the 20th century. Indians even migrated to Great Britain’s territories in the Caribbean as indentured servants—in Guyana, in northern South America, over 40% of the population is of “India-Indian” descent.

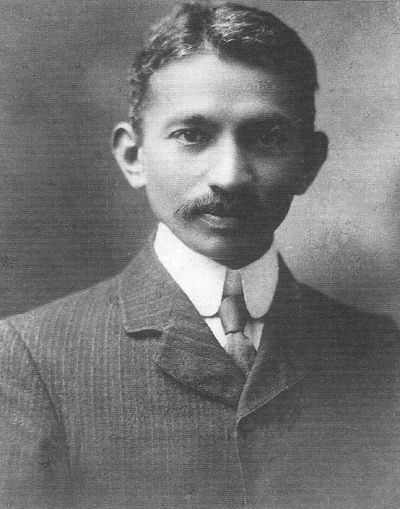

The story of Mahatma Gandhi, who later helped lead India to independence, is an example of a native trained to manage the Empire. After an education in a British school in India, Gandhi went to London and studied law. On graduating he went to South Africa to serve the British Empire as a lawyer for twenty-five years before beginning a new career advocating for Indian independence. This, too, was a pattern duplicated in other European empires: eventually, educated local elites and professionals would begin to demand greater autonomy, if not outright independence, since they were already administering the colonies for the “mother country.” Ho Chi Minh, who would fight with and then against U.S. forces for the independence of Vietnam, applied for admission to the French academy in Marseilles that trained imperial administrators. If the school had accepted him, history might have been quite different.

Neo-Imperialism in Latin America

Latin America achieved independence from Spain and Portugal in the first decades of the 1800s. Great Britain was particularly interested in an independent Latin America as a source of markets for its industrial products, while English and Irish mercenaries, available after the Napoleonic Wars, joined the fight for freedom alongside Bolivar and others in Latin America. The Spanish and Portuguese became the first Europeans to begin losing their overseas empires, nearly 150 years before the British, French, and others would go through the same process. The new countries of Latin America suffered through a long period of struggle to establish stable governments and thriving economies—which, depending on the country, included civil wars, dictatorships, social and political reforms, and economic dependence on a handful of exports and their international price.

The new countries also were the first to experience neo-imperialism—a “new” imperialism that technically respected national sovereignty, but in reality forced governments to bend to foreign influence. In the 1820s and 1830s, the new governments of Latin America quickly became indebted to British banks, which had arranged large loans in anticipation that independence would bring rapid economic development as it had in the United States. Meanwhile, local artisans could not compete with British textiles and other manufactured goods that flooded the markets of the new republics. Many countries became dependent on the international price of a handful—or even a single—export such as copper and nitrates in Chile, coffee in Brazil, beef and grain in Argentina, sugar in Cuba, and bananas in Central America. British investors in Latin America were followed by French and U.S. businesses. This neo-imperialism continues for much Latin America well into the 21st century, while the model was extended to new countries formed in Africa and Asia from the declining European empires after World War Two.

Some Latin America countries had more success than others boosting their economies with world trade. Brazilian plantations still produce more coffee beans than any other country, but in the 19th century, more than half of all coffee came from Brazil. But the country’s economy was extremely sensitive to the world price and rate of consumption; and when the occasional frost in southern Brazil damaged the coffee bushes, planters could go bankrupt.

Brazilian coffee also affected politics and human rights. Brazil was the last country in the hemisphere to abolish slavery, but it achieved this change without a bloody Civil War. In the 18th century, enslaved labor was shifted from declining sugar cane plantations in northern Brazil to silver mining districts in the south. As the mines were beginning to deplete in the late 18th century, planters discovered that coffee grew well in the highlands of southern Brazil, and again, the large landowners used enslaved labor to cultivate the bean. The bloody War of the Triple Alliance, in which Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil fought Paraguay over borders from 1866 to 1870, contributed to the end of slavery. Desperate for soldiers, the Brazilian government offered freedom to enslaved men if they served in the army. Impressed with the ability and dedication of these soldiers, many army officers began to feel that slavery should end in their country. The institution was gradually fading anyway, because coffee cultivation used less labor than either sugar plantations or mines. By 1880, nearly three quarters of all people of color in Brazil were free. King Pedro II finally abolished the institution in 1888; a year later, he abdicated and the military organized a republic.

As noted in the last chapter, Chile controlled over 80% of the world’s nitrates in the 1880s, making it a serious power in the Pacific. After the War of the Pacific, the Chilean Navy controlled the west coast of South America, Central America, and was even a threat to U.S. interests. In 1885, when a rebellion broke out in the Colombian province of Panamá, the U.S. government sent ships and troops to both sides of the isthmus to protect the railroad owned by North American investors. The Chilean government send its British-built armored cruiser Esmeralda (the fastest ship in the world when launched the year before) to the Pacific side of Panamá, to send a message that it would prevent any annexation of the isthmus by the U.S. Whatever its intentions, the U.S. government withdrew its navy and troops after the rebellion had calmed, as U.S. naval observers opined that the mighty Esmeralda could sink every ship in the U.S. navy at the time. The incident contributed to the building of a more effective U.S. navy in the ensuing years. The sense of vulnerability also intensified U.S. interest in a canal through the isthmus of Panama, which had been begun in 1881 by a French consortium led by Ferdinand de Lesseps (the man behind the Suez Canal).

U.S. Imperialism

After the Latin American independence wars in 1830, the Spanish Crown still maintained control over Cuba and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean and the Philippine Islands in the Pacific. With the end of slavery, independence inspired Cubans, including a few from the planter class. José Martí, a Cuban intellectual and poet, organized funds and support in the United States for a new push to liberate his homeland, and a new rebellion began in 1895. Martí died in his first battle, but the independence army continued with guerrilla tactics in their fight against the Spanish. The Spanish set up concentration camps for non-combatants, assuming that anyone who did not submit was an independence sympathizer. Thousands died in terrible conditions in these camps.

Major newspapers soon engaged in sensationalist reporting on Spain’s crimes in Cuba in order to increase circulation. Media magnates William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer used what became known as yellow journalism to agitate for war. Yellow journalism, named after a popular cartoon character, “Yellow Kid”, is the technique of using inflammatory headlines backed by little or no factual reporting to stir up public emotion, a combination of the click-bait and fake news that is common on the Internet today. It’s ironic that Pulitzer is now best known for the prize for journalistic excellence he established in his will.

At the beginning of 1898, public opinion in the US was divided over entering the Cuban war for independence. Still, the McKinley administration was alarmed enough about instability on the island that it sent the battleship Maine to Havana in order to protect U.S. interests. These were plentiful: U.S. investors and buyers controlled the all-important sugar industry, they built and owned much of the communications and transportation infrastructure, and U.S. smokers were the main consumers of Cuban cigars. The Maine mysteriously blew up in Havana harbor, killing scores of U.S. soldiers. The Spanish were immediately blamed by the sensationalist U.S. press (decades later, investigations showed that the explosion came from the inside and was an accident: the munitions room was located alongside the engine room!). President McKinley asked for and the U.S. Congress granted a declaration of war on Spain. The conflict quickly eliminated the Spanish Empire’s control of Cuba and Puerto Rico. Theodore Roosevelt, Secretary of the Navy at the time, formed his own army unit he called the Rough Riders so that he would not miss out on the “splendid little war” in Cuba. However, Black troops from the regular army had to save him and his men at the Battle of San Juan Hill.

The most important fighting of the ten-week war was really at sea. The U.S. navy sank the Spanish fleet in the Caribbean and in the Philippines, denying any possibility of the arrival of reinforcements and war materiel from Spain. At the end of 1898, the Spanish Crown agreed to Cuban independence and handed over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the U.S. Cuba Libre (“Free Cuba”) was shouted for years by Cuban nationalists. Appropriately, it became the name for the classic bar drink “rum-and-coke” in Spanish-speaking countries: the combination of U.S. Coca Cola and Cuban rum. However, Cuba was far from “free” after the war, since the U.S. government demanded the right to intercede in the internal affairs of the island for any reason. The infamous “Platt Amendment” was forced into the constitution of the new Cuban republic, and U.S. Marines were indeed sent in periodically to change governments or put down rebellions, real or imagined. U.S. investors were particularly leery of increased Afro-Cuban participation in politics, projecting their own racism onto the affairs of the island.

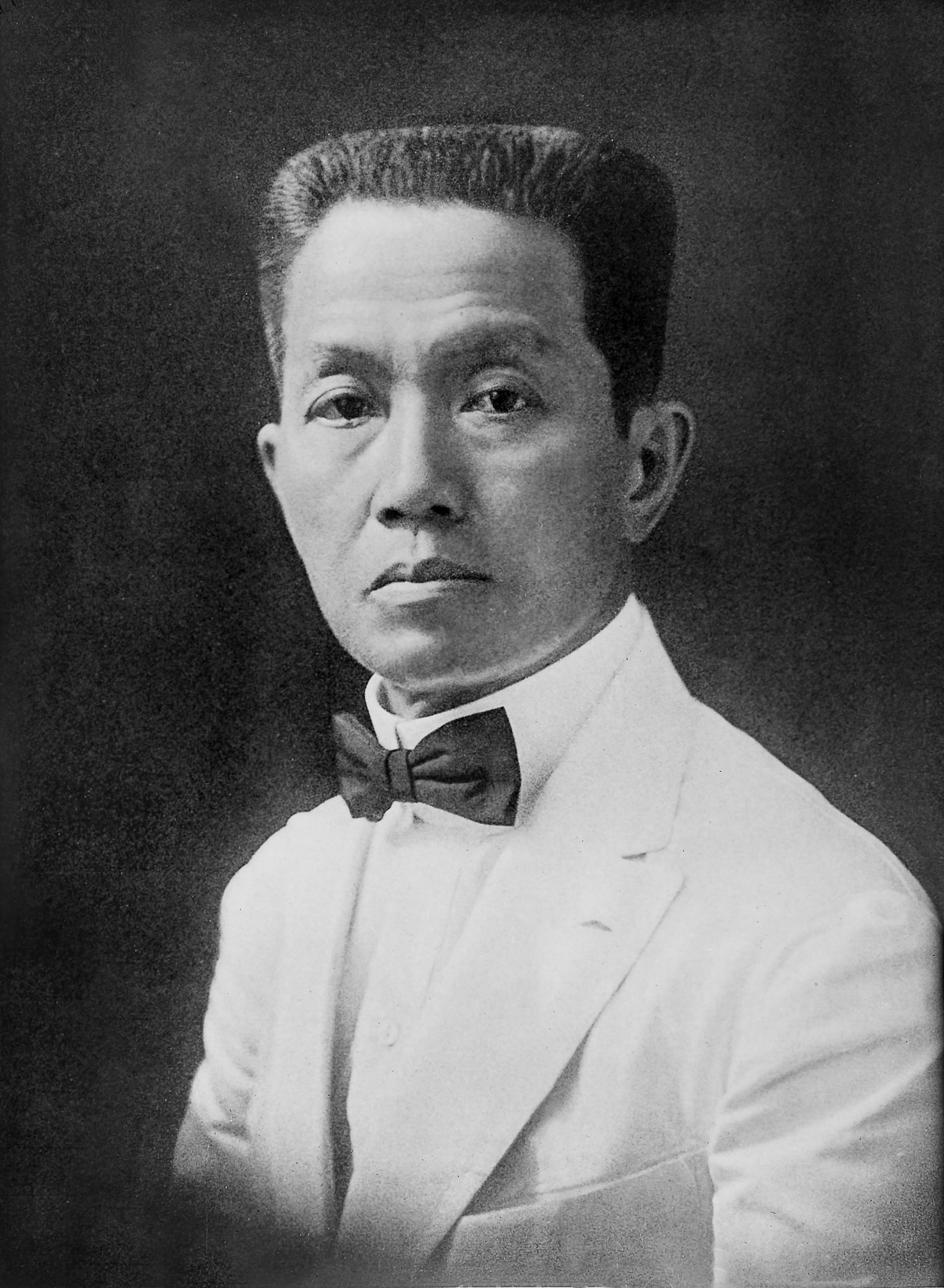

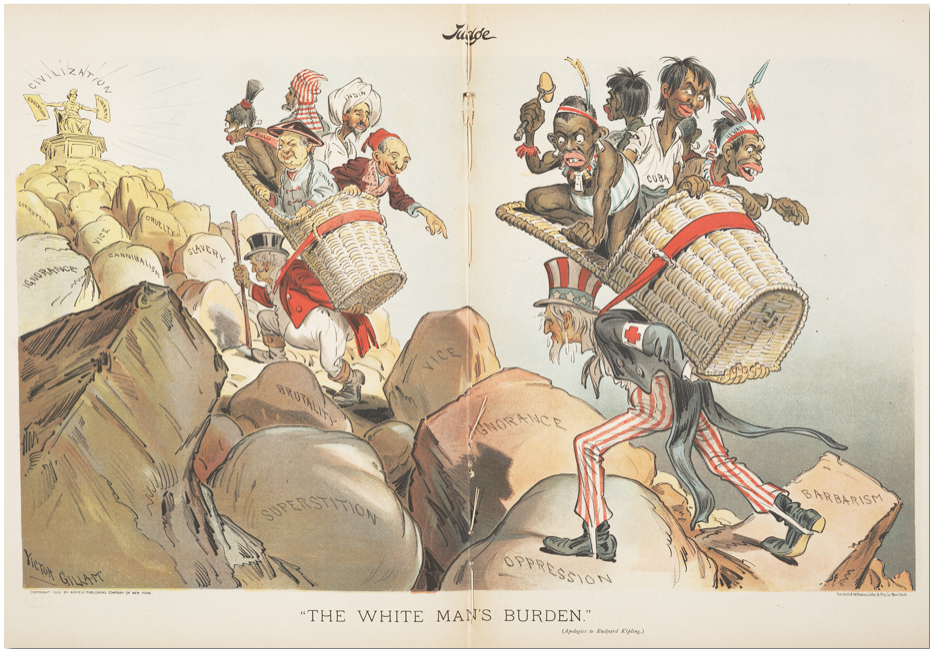

Meanwhile, the U.S. annexed Puerto Rico and Guam, which are still U.S. territories, as well as the Philippines. Filipinos had already been fighting a war for independence since 1892, so they objected to becoming a possession of the U.S. Emilio Aguinaldo, the Filipino leader, had been promised the US would recognize the independence of the Philippine Republic, but when the time came, President McKinley issued a proclamation of “benevolent assimilation.” Rudyard Kipling’s famous 1899 poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” was written in support of the U.S. effort to subdue the ungrateful brown people of the Philippines. The U.S. Navy destroyed the city of Iloilo to suppress the independence movement, and Aguinaldo called for a strategy of guerrilla warfare. 4,200 American soldiers were killed in the conflict and about 250,000 Filipino soldiers and civilians. In 1901, Aguinaldo was captured and forced to surrender. Resistance continued until 1913, but by 1902 most of the guerrillas had been pushed way from major cities. The Philippines finally achieved independence in 1946, after World War Two (which included wartime occupation by Imperial Japan).

The European “Scramble for Africa”

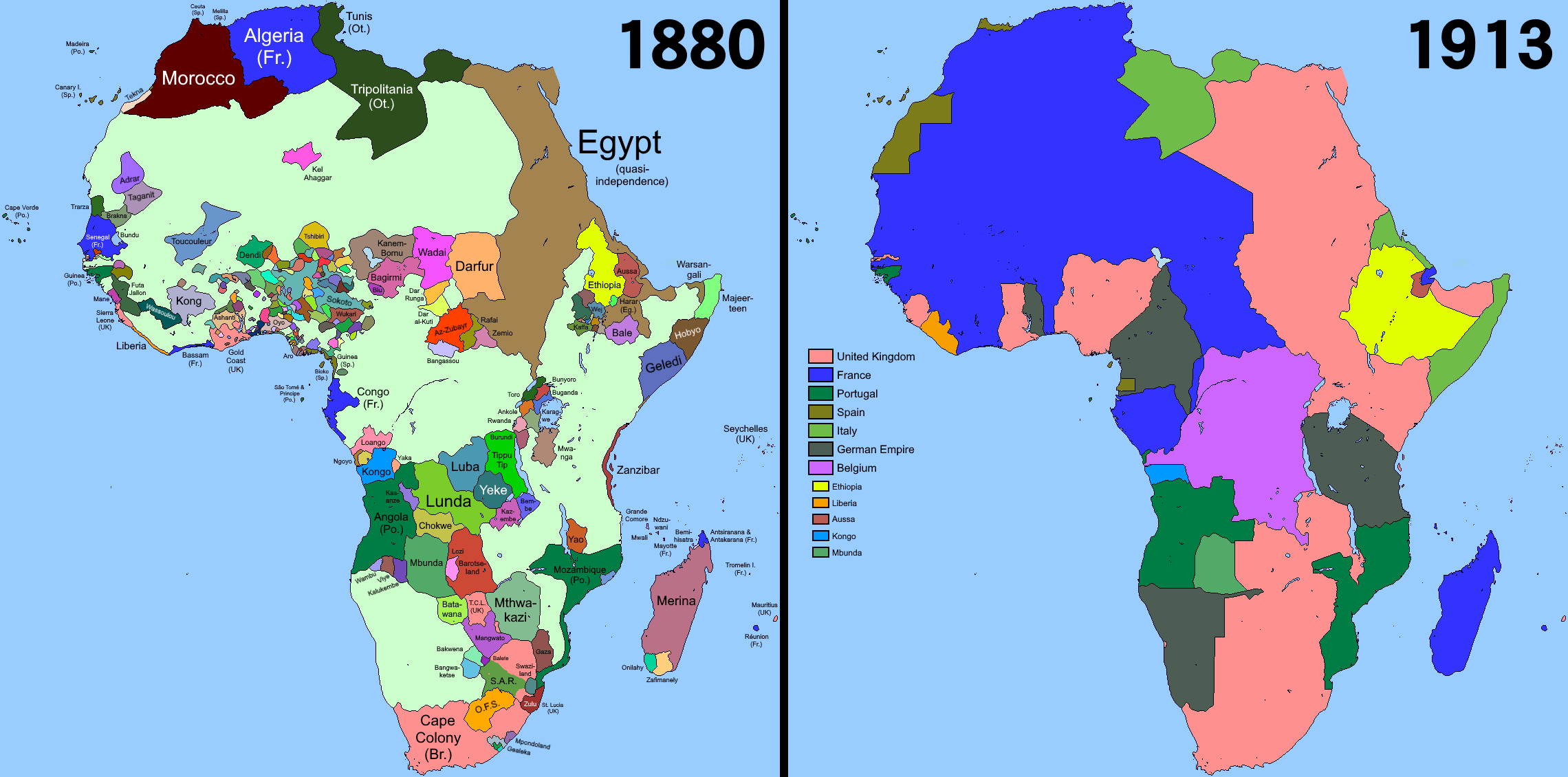

The European scramble for Africa at the end of the 19th century was motivated by international rivalry and by the fact that Africa south of the Sahara remained the last part of the world “unexplored” by Europeans. South Asia was part of the British Empire, East Asia and Oceania were divvied up, and the Americas were either already colonized or had established republics whose existence was accepted by Europeans and the U.S. The rivalries among the Europeans were based on the desire to create captive consumer markets for their manufactures and to secure resources like copper, tin, cotton, rubber, palm oil, tea, cocoa, and coffee upon which their industries depended.

After the British began enforcing an end to the Atlantic slave trade in 1808, European contact with most of sub-Saharan Africa consisted of trade for ivory and other goods at a handful of trading posts. Belgian King Leopold and the new German Empire began the scramble in the 1870s, sending explorers to claim African territory, much like the Spanish in the Americas 350 years before. The Portuguese in Africa defended their pre-existing arrangements, while the British and French began to rush deeper into the continent. The Europeans made agreements with many local kings and chieftains and went to war with others, always seeking a pledge of loyalty to their particular empire.

To bring order to the “scramble”, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1884 organized a conference to delineate claims. The Berlin Conference was attended by representatives from 13 European powers plus the United States. No African countries were represented except for the Ottoman provinces along the Mediterranean. Administrative boundaries deliberately cut across existing political and ethnic boundaries, in some cases forcing warring groups to live and work together, in others dividing tribes and their allies. This weakened resistance in the short run, but, as will be examined in a later chapter, became a source of civil unrest, separatist movements, and boundary disputes among the new African countries formed in the 1950s and 60s.

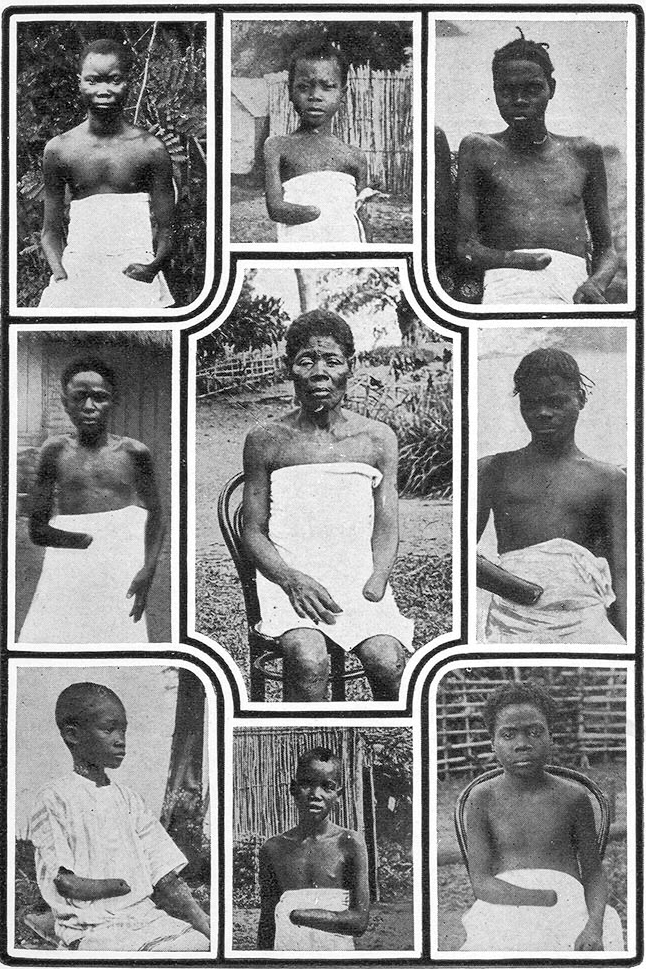

Along with the usual proposal of “civilizing” the non-European peoples of their empires, the imperialists also claimed that they were committed to ending the internal slave trade. However, European treatment of African laborers often included whipping, torture, and other punishments, alongside debt peonage. It was standard practice in the so-called “Congo Free State” (really the personal fiefdom of King Leopold of Belgium) to cut off the hands of African workers who did not meet their rubber collection quotas. The international outcry over such practices forced the Belgian government to finally take over Leopold’s holdings in 1908, after thirty years of brutal rule.

South Africa was a special case in European imperialism: the Dutch made it into a “settler colony” beginning in the mid-1600s, rather than merely establishing a trading post. They were interesting in forming a community of farmers that could supply the fleets rounding the Cape of Good Hope on their way to the East Indies. Thousands of Dutch and other Europeans were attracted by the relatively cooler climate of southern Africa and plentiful arable land; and like the British and the United States in North America, they were more interested in removing the natives rather than subjugating them.

The British took control of the territory from the Dutch during the Napoleonic period. In the 1830s, the imperial government began abolishing slavery and requiring English in schools and in legal transactions. In reaction, many Dutch settlers moved farther inland in the “Great Trek”, taking more land from the natives and establishing two republics, Transvaal and the Orange Free State. At the same time, the descendants of unions between Europeans, Africans, and natives of the Dutch East Indies brought in as laborers (collectively known as “coloured”) occasionally established their own autonomous regions.

The British also faced the Zulus, who, led by their extraordinary leader Shaka Zulu and his well-trained army, had established an independent kingdom in eastern South Africa in the 1820s. When local British commanders decided to attack a growing military threat from the Zulus in 1879, the imperial regiments were defeated by Zulu troops in a series of major battles. A second invasion of Zululand was successful, but the British continued to recognize Zulu autonomy in much of their territory.

The descendants of the Dutch settlers called themselves “Boers” (the Dutch word for “farmer”) and successfully repelled a British invasion in 1881. They were defeated in the Second Boer War (1899-1902), after a bloody conflict that included a wide guerrilla war and concentration camps for Boer civilians. A young Winston Churchill, the future Prime Minister of Great Britain, went to South Africa as a journalist to report on the war, and instead was captured by the Boers. Churchill escaped and his story of heroism helped launch his career in British politics. The Germans, who held territory bordering South Africa, supported the Boers in the conflict, adding to the accumulating disagreements between the governments of Great Britain and Germany on the eve of World War One.

Soon after, in 1910, the British organized the Union of South Africa, including the Boers as equal citizens, while continuing to deny such equality to the coloured and native groups (nearly 85% of the population). This new Union was effectively an autonomous dominion within the British Empire, much like Canada.

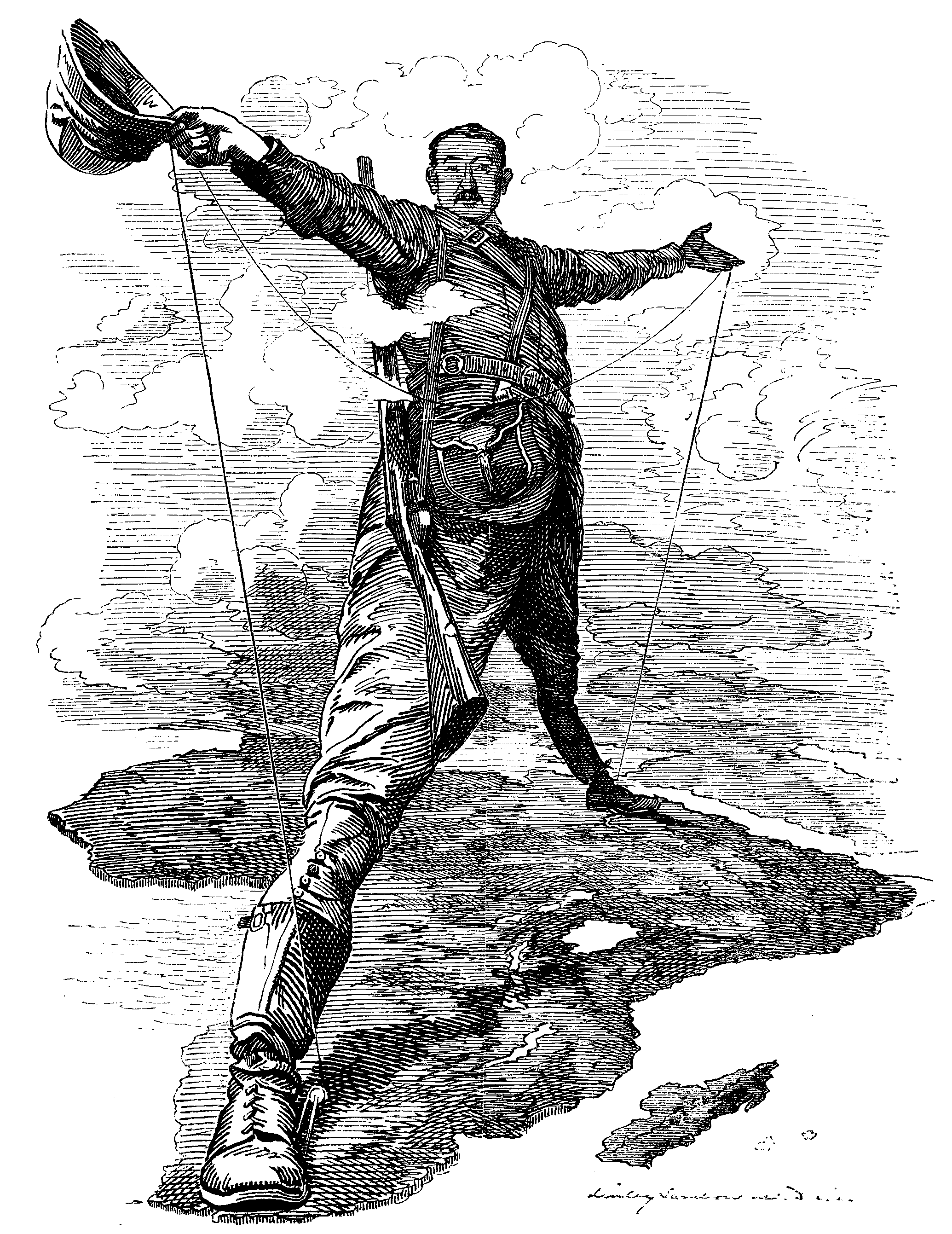

Cecil John Rhodes is now probably most remembered for the scholarship he endowed in his will in 1902 that funds study at Oxford for U.S. college graduates. Rhodes Scholars include Bill Clinton, Rachel Maddow, Bobby Jindal, and Kris Kristofferson. Rhodes Scholarships do a lot for the memory of Cecil Rhodes, just as the Nobel Prize does a lot for the memory of Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite whose company operated over 90 munitions factories during his lifetime.

Rhodes endowed the scholarship at Oxford because the British University was his alma mater. The son of a well-connected Anglican minister, Rhodes joined his brother in 1871 in South Africa at age 18, to recuperate from tuberculosis. He dabbled in farming and then, financed by the Rothschild bank that had helped Britain buy the Suez Canal, began buying diamond mines. Rhodes returned to England to attend Oxford, but left after a year to resume his diamond business, eventually founding the De Beers Company in 1888. A year later, Rhodes controlled 90% of the world’s diamond production. De Beers currently operates in 35 countries and held onto its monopoly until the start of the 21st century. The company still sells about 35% of the world’s diamonds.

During his year at Oxford, Rhodes absorbed the philosophy of imperialism. He attended a lecture by professor John Ruskin that became a famous justification for empire, called “Imperial Duty.” Ruling the world, Ruskin said, “is a destiny now possible to us—the highest ever set before a nation to be accepted or refused.” Rhodes took this idea back to Africa, and once declared “We are the finest race in the world and the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race” As noted, the British were not the only people who believed themselves to be superior to the people they conquered. Europeans and the Americans also believed it was their job to help “civilize” the rest of the world. The “White Man’s Burden” and the “Civilizing Mission” of imperialism were big themes – we still call countries in what was once described as the “third world” as “ developing nations,” as if the goal of all the nations in the world is to become like Europe and the United States, who have a responsibility to help them do just that.

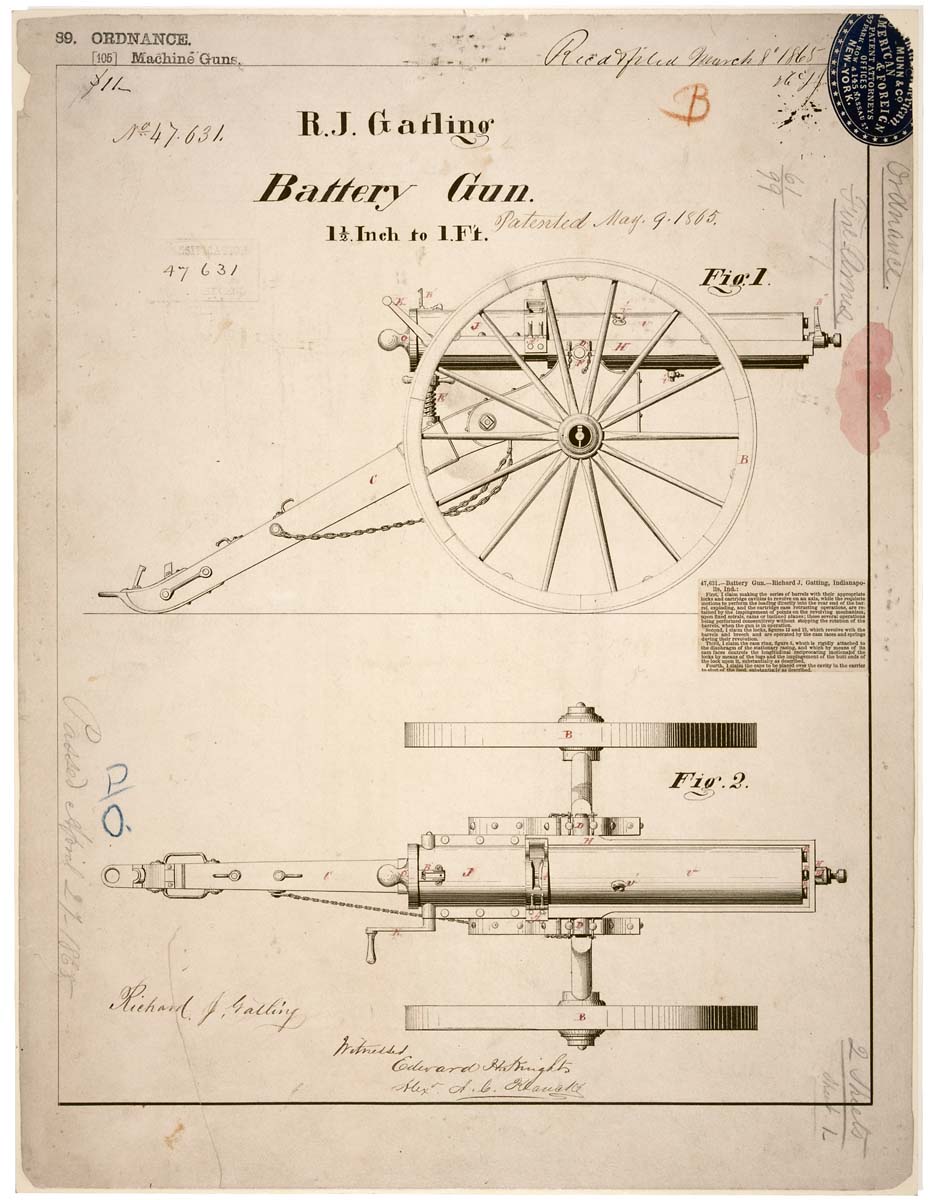

In reality, the superiority the British, French, and Americans had over the people of “less developed” nations was mostly in military technology. Britain demonstrated the effectiveness of armored steamships during the Opium Wars. They sailed up the Yangzi River and threatened the Grand Canal and Beijing, forcing the Chinese to surrender and agree to the unequal treaty. In the 1870s the British began using Gatling hand-cranked machine guns against the Zulu in Africa and the Bedouin in the Middle East. The Royal Navy used them against the Egyptians in 1882 during Egypt’s civil war. The US used them to support American troops during the Battle of San Juan Hill when Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders made their famous charge.

Later the British switched to the Maxim gun, which was the first recoil-operated machine gun and was able to fire 600 rounds per minute. They used it in the 1890s to conquer the Ndebele kingdom in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Cecil Rhodes, who was by this time Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, had about 750 South Africa Company Police against 80,000 tribal spearmen and 20,000 riflemen. But they had Maxim Guns. In one battle, the British used Maxim Guns to “fight off” 5,000 attacking Zulu warriors. In 1898 the British were able to kill 20,000 Sudanese warriors with four Maxim Guns in a few hours without taking many casualties. This was the beginning of a period of asymmetrical warfare based on technology that continues to the present – and forced people who could not stand up to the imperialists’ superior weapons to find other ways to resist.

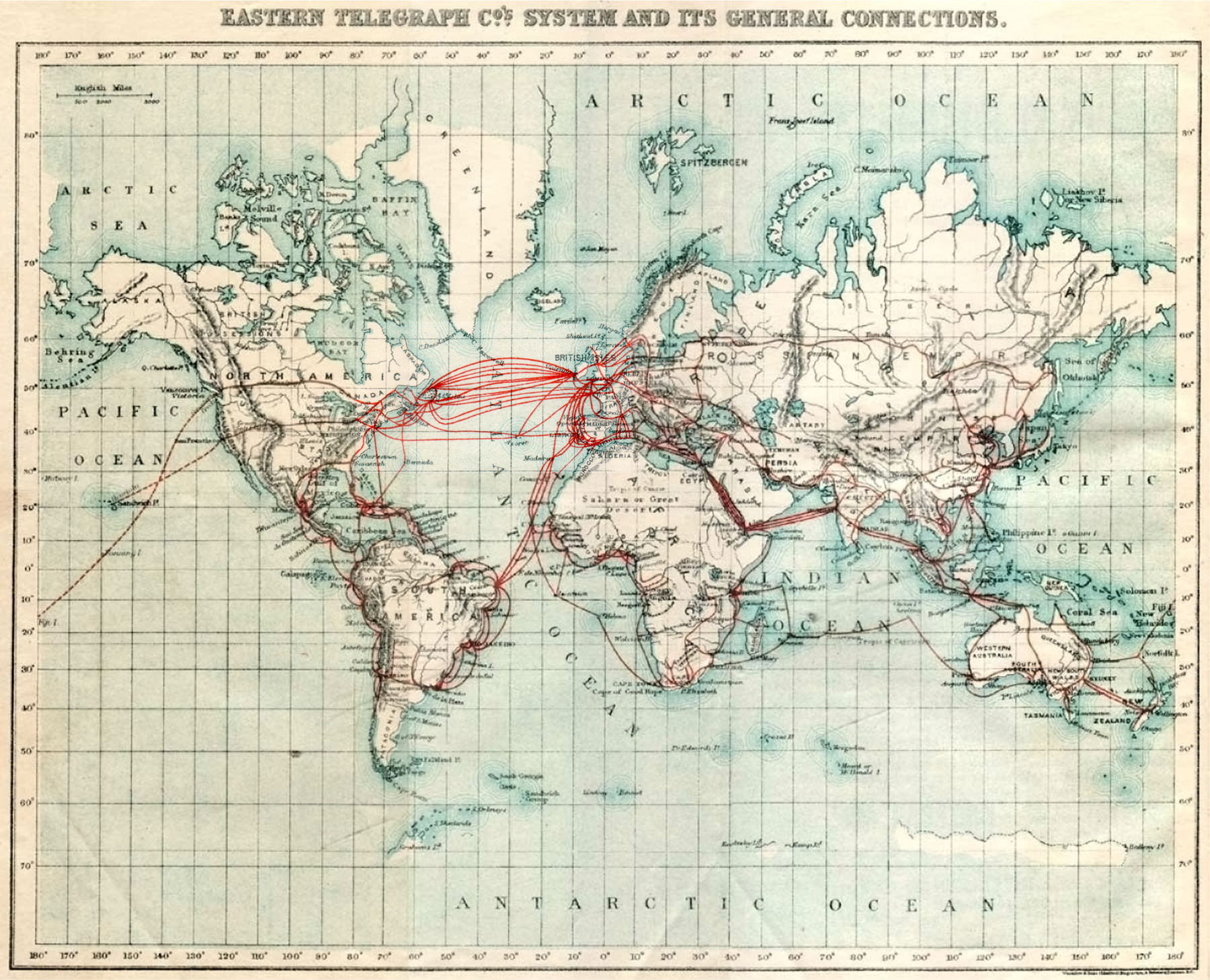

In addition to weapons and transportation, Europeans and Americans had the added advantage of communications. Telegraphs using Morse code became widespread in the U.S., Britain, and Europe during the 1850s, but undersea cables were required to connect the colonies. Before telegraphy, a letter from London took about two weeks to reach New York or Alexandria Egypt, a month to reach Bombay on the west coast of India, six weeks to reach Singapore or Calcutta on the East side of India, two months to get to Shanghai and ten weeks to arrive in Sidney Australia. A successful undersea cable line between Britain and the US was completed in 1866, and Britain and India were connected in 1870. Australia was linked to the system in 1872 and a trans-Pacific cable was completed in 1903 linking the U.S. with Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines. Although telegraphy had been pioneered by Americans like Samuel Morse, the British dominated undersea cable. At the end of the 19th century, Britain owned 24 of the world’s 30 cable-laying ships and the British owned and operated 2/3 of the world’s cable. During World War I, British telegraph communications were almost completely uninterrupted while Britain was very successful cutting German cables, forcing the Germans to rely on wireless (radio) transmissions that were easy to listen and decipher.

Europeans treated their military success over colonized people as proof of their cultural superiority. They developed theories of scientific racism and Social Darwinism to justify their choice to treat conquered peoples as less than fully human. They also took advantage of previous African customs and tribal animosities to divide the conquered Africans, or created new ones based on their own prejudices. In Rwanda, the Belgians noted the existence of separate castes that lived side-by-side for generations under the same rule. However, the Belgians decided to put the cattle-raising Tutsis, ten percent of the population, over the Hutu farmers. Because of more access to animal protein, the Tutsis seemed taller and better-looking to the Europeans and were deemed to be naturally superior to the Hutus. After independence, the Hutus took control and subjected the Tutsis to periodic pogroms. In 1994, nearly a million Tutsis were killed by their neighbors in a government-orchestrated genocide, until a largely Tutsi-led guerrilla insurgency took over the government. Both groups speak the same language, and the distinctions fostered by the Belgians have officially disappeared. However, in the aftermath up to 2 million Hutu refugees fled Rwanda for the Congo, exacerbating the humanitarian crisis and destabilizing central Africa even further.

China and Japan

Finally, as we always do, let’s look at what was happening in the world’s biggest nation. The Chinese Empire continued its decline, as Europeans continued their presence in assigned trading ports, divvying up Chinese territory into “spheres of influence” in which commerce and Christian missionary activity was controlled by a particular European power. By the 1890s, however, China also faced the rapidly industrializing Japanese Empire. In less than thirty years, the Japanese reconstructed their government, initiated industrial activity, and built up their military through conscription and the latest weapons and ship technology. However, the Japanese home islands lacked deposits of key industrial inputs, chiefly coal, iron ore, and oil. To acquire guaranteed resources and markets, the Japanese government began to play the imperial game, following the rules established by the Europeans. Like the British in India and China, Japanese commerce laid claim to their own “sphere of influence” in Chinese territory, and claimed sovereignty over tributary states. The brief Sino-Japanese War in 1895 ended with the Qing Empire granting the Ryukyu Islands and Taiwan to Japan, and ceding trading rights in Korea and Manchuria.

At the end of the 19th century, a final conflict with the West would pave the way for radical change and the end of the Qing Empire in China. The Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) was an anti-colonial, anti-Christian revolt led by martial artists who called themselves the Righteous Fists, or “Boxers” by Westerners. The Boxers, believing they were impervious to foreign weapons, marched into Beijing intending to help the imperial government exterminate the foreigners. An eight-nation alliance, which included European nations, the U.S., and Japan, sent 20,000 troops to fight the Boxers. The foreign soldiers freed the legations besieged in the capital, but they also looted Beijing and the surrounding countryside and summarily executed anyone suspected of being a Boxer. The Qing government agreed to pay an indemnity of 450 million taels of silver to the allies (worth about $10 billion today).

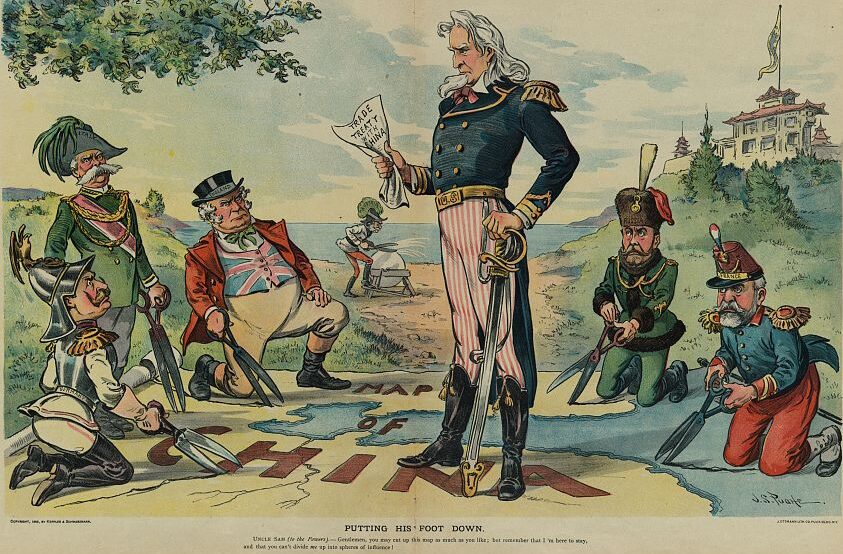

The abject state of the Qing dynasty and the increasing regional power of Japan set the scene for China to become a battlefield for territorial conflicts between Russia, Japan, and the United States. The United States acquired the Philippine Islands from Spain after the 1898 war, and immediately began projecting its own political and commercial power into East Asia. Coming late to the imperial game in China, the United States sought to limit the existing “spheres of influence” and prevent new ones from being imposed by either Russia or Japan. U.S. diplomats advocated an “Open Door Policy” in China, in which the Qing Empire would not limit any commercial activity by outside powers.

In 1900, Russia occupied Manchuria and came into conflict with Japanese interests on the Korean peninsula, leading to the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. After the Japanese navy sank the main battleships of Russia’s Pacific fleet in the Battle of Port Arthur and held off the Russian army, the world realized the power of an organized and industrialized Japan; forcing the Europeans and Americans to consider the Japanese Empire as an equal, while inspiring non-European colonized peoples that the Europeans were not always invincible in war.

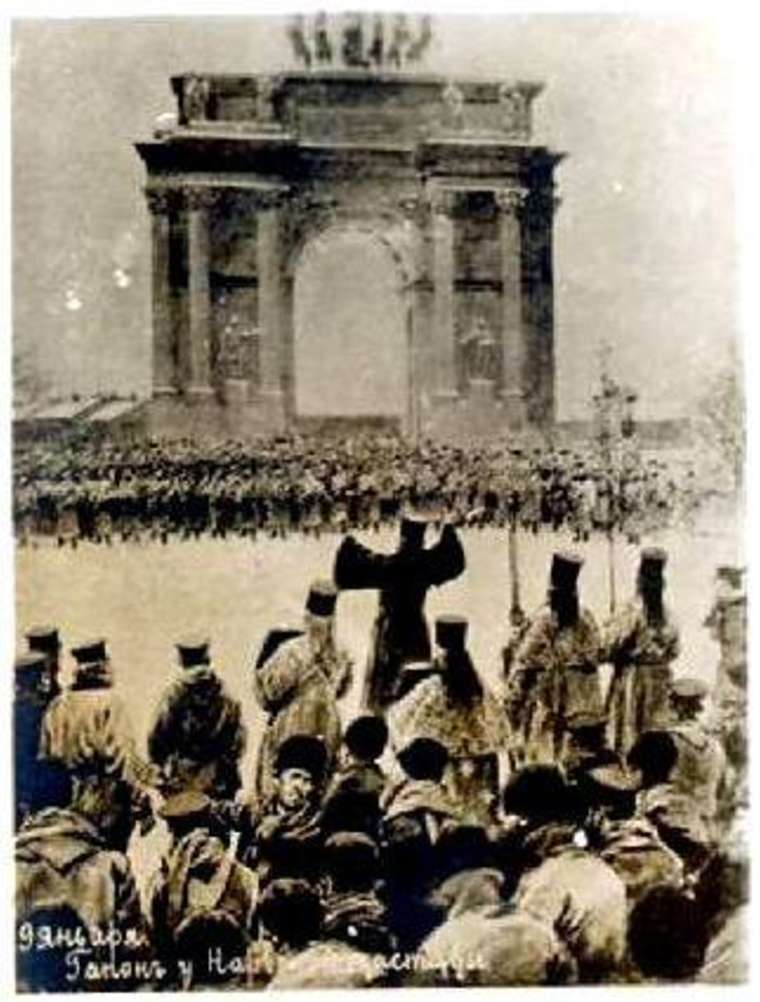

From the Russian side, however, defeat by the Japanese on the battlefield and on the seas was not only humiliating, but highlighted the ineffectiveness of the Tsarist regime. At the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in January 1905, a major protest against the inept government ended when the Palace guard fired upon the peaceful demonstration, killing hundreds. This “Bloody Sunday” increased demands for reform, including widespread support for a parliamentary monarch. In the meantime, the Tsar sent most of the Russian Baltic Fleet to retake Port Arthur from the Japanese. Two thirds of the ships were sunk by the Japanese Combined Fleet in the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905. In October 1905, Tsar Nicolas II acquiesced to the formation of an elected parliament, the Duma, and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy. However, he soon reneged granting full oversight powers to this new legislature, preferring to maintain himself as an absolute monarch.

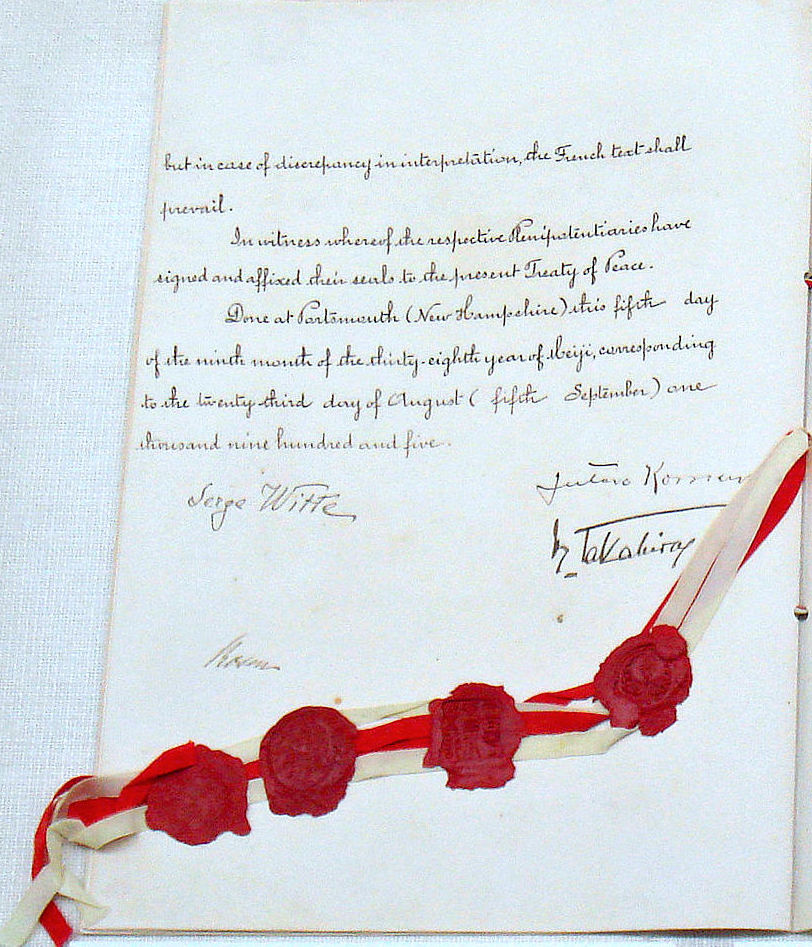

However, the Tsar also agreed to end the unpopular war with Imperial Japan. Peace between the Russians and Japanese was negotiated in Portsmouth, Maine, in the United States, highlighting the increasing importance of U.S. interests in East Asia. President Theodore Roosevelt was awarded the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in ending the war. Japan took over Russia’s “sphere of influence” on China’s Liaotung Peninsula and was recognized as the sole power in Korea, which became part of the Japanese Empire in 1910.

The Russo-Japanese War also once again highlighted the extent to which the Qing government in China was hardly considered a factor in international relations. Even though the war concerned Chinese territory, Chinese armies were not seriously involved in the fighting; nor were Chinese negotiators present at the Treaty of Portsmouth. By that time, the Qing empire was devolving into a series of warlord-controlled regions. Palace intrigues in the royal “Forbidden City” in Beijing had led to effective power being wielded by the Empress Dowager Cixi for nearly five decades until her death in 1908. Although she at times embraced gradual reform of her government and military and periodically protested European and Japanese incursions, she was realistic enough to understand her limits. More conservative forces took over in the palace in 1908, installing the five-year-old Prince Puyi as Emperor. It was not long before modernizing forces soon overthrew the decadent imperial system.

The most inspirational leader of the modernizers was Sun Yat-sen. Born in 1866, he moved to the then-independent Kingdom of Hawaii, where an older brother owned a farm, to complete is secondary education at a U.S. missionary school. Sun went on to study medicine in Hong Kong and began advocating for the end of the Qing dynasty and the establishment of a Chinese republic. Because of his opposition to the Qing, Sun lived in exile in Hawaii, Japan, and Malaysia, from where he formed the alliance which would end the Qing regime in the Xinhai Revolution in 1911.

Media Attributions

- service-pnp-ppmsca-25600-25696v

- 2880px-OttomanEmpireMain

- William_Simpson_-_Charge_of_the_light_cavalry_brigade,_25th_Oct._1854,_under_Major_General_the_Earl_of_Cardigan

- SuezCanal-EO

- Grigoriy_Myasoyedov_Reading_of_the_1861_Manifesto_1873

- Russia_ethnic

- 2880px-Austria_Hungary_ethnic.svg

- Otto+von+bismarck

- Wernerprokla

- JaMAC

- Canadian_Pacific_System_Railmap

- LEAD Technologies Inc. V1.01

- File written by Adobe Photoshop? 5.0

- Gauchos_mateando

- JoseMartiStatue-CentralParkNY

- West_minstrel_jubilee_rough_riders

- 2560px-Emilio_Aguinaldo_ca._1919_(Restored)

- _The_White_Man’s_Burden__Judge_1899

- Scramble-for-Africa-1880-1913-v2

- Kongokonferenz

- MutilatedChildrenFromCongo

- KingShaka

- Punch_Rhodes_Colossus

- GatlingGunDrawing

- 1901_Eastern_Telegraph_cables

- 2560px-China_imperialism_cartoon

- Putting_his_foot_down

- Gapon_crowd_1905

- Japan_Russia_Treaty_of_Peace_5_September_1905

- Sun_Yat_Sen_portrait_2