8 Modern Crises

The horror of World War I was a shock to the self-satisfaction of Europeans who had believed themselves to be the pinnacle of world civilization. Intellectuals had shared in the celebration when war had been declared, parading in the streets of many national capitals. It is unclear exactly what they were expecting from the war, but their experience was quite different. No one exposed to the misery of trench warfare could hang onto illusions of the heroism and nobility of the struggle they were engaged in. The cold, the mud, and the terror of pointless charges over the top ordered by commanders who had no clue what they were doing and who rarely led their men into the slaughter – all these factors were captured by journalists and then by novelists like the American Ernest Hemingway (A Farewell to Arms, 1929), the German Erich Maria Remarque (All Quiet on the Western Front, 1929), and the British Ford Madox Ford (The Good Soldier, 1915, and Parades End, 1925) and Robert Graves (Goodbye to All That, 1929). The absurdity of Western culture was on display in what has come to be known as the modern crisis. The trenches had also been an unusual opportunity for the classes to mix. Some upper-class British officers such as Ford developed a new understanding of people they probably would never have met in their normal lives at home. Other novels dealing with these themes include German author Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain (1924), Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier (published in England as the war was ending in 1918), and even Virginia Woolf’s most famous book, Mrs. Dalloway, where one of the main characters, Septimus Smith, is a war veteran suffering hallucinations caused by what we might now call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)—what was then called “shell-shock.” Smith avoids being committed to a mental institution by jumping out a window to his death.

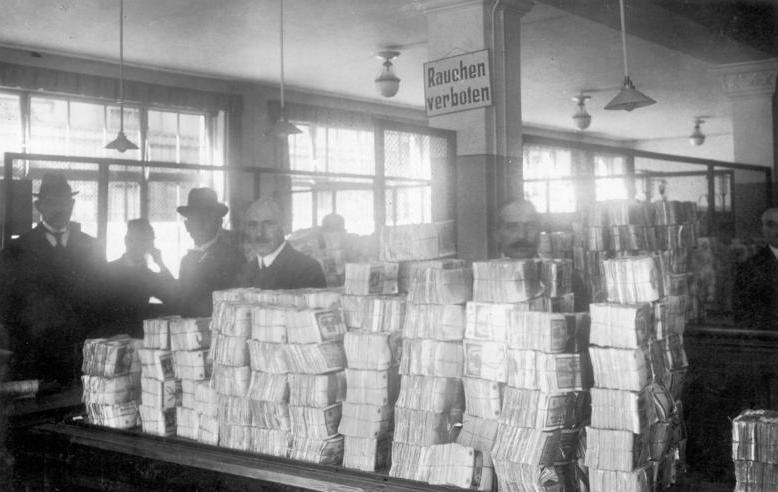

Hyperinflation

Peace began in Europe with the hope that the new nation-states that replaced the German, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian Empires in Central Europe would deliver social justice and prosperity through new democratic constitutions. Not everybody was willing to wait patiently for life to get better after the war and pandemic, however. And the new Soviet Union, which had survived attempts by the allies and the U.S. to defeat the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War, felt justified in trying to export their “workers revolution” to the rest of Europe. Attempts at violent communist-inspired revolution led to violent reactions. Revolutionaries found support among the workers of many nations. Many believed the bloodbath in the trenches had to have meant something more than just gaining the right to vote—perhaps it was to birth a new socialist utopia, replacing the not just the monarchs who started the war, but the capitalists who profited from it.

In Germany, liberals and social democrats had declared a republic when Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated in the final days of World War One, with the hope that they could negotiate a peace as equals with the democratically-elected governments of Great Britain, France, and the United States. However, just weeks later, Bolshevik-inspired revolutionary actions like the Spartacist Revolt in Berlin were brutally suppressed by the new German government with the help of the paramilitary Freikorps—troops returning from the front who, having just fought for their nation, did not want Germany taken over by a “foreign” socialist revolution.

Although the new government was not treated as an equal by the Allies at Versailles, delegates elected from all over Germany met at Weimar, the cultural capital of Germany, at the same time to write the most representative constitution in the world, which was adopted in August 1919. The Weimar Republic included an elected president and parliament, the Reichstag, as well as a chancellor who organized a cabinet of government ministers. Elections were based on proportional representation, which almost always results in a multi-party government. The spectrum of political parties included pro-Republic social democrats, liberals, and Christian democrats in the middle, with anti-democratic nationalists, monarchists and fascists on the right, and revolutionary socialists and communists on the left. This wide range of political orientations was typical in most European democracies between the world wars.

All the countries of Europe, both old and new, faced massive unemployment and inflation after the war as their economies readjusted and veterans returned to the workforce. However, these problems were magnified in Germany because on top of everything else, under the Versailles Treaty, the new government had to pay reparations to the Allies in the form of gold, coal and timber. By 1923, the Germans were unable to keep up with coal deliveries (any of the richest coal fields of Imperial Germany were now part of the new country of Poland); so French and Belgian troops moved in to occupy the northwestern Ruhr Valley, location of much of German industry. The German government encouraged a widespread strike to protest the occupation, which it funded funded by printing more paper money. Like nearly all of the world’s currencies, the German Deutschmark had originally been backed by gold, but the Kaiser had taken the country off the gold standard at the beginning of the war. Germany had expected to capture territory that would pay for its war expenses, but defeat and reparations changed the situation drastically. Printing more Deutschmarks decreased the value of each one, until ultimately they were not worth the paper they were printed on.

The 1923 Weimar German inflation became a textbook case of hyperinflation. At the end of World War One, 170 Deutschmarks bought an ounce of gold; by January 1923, at the start of the occupation of the Ruhr, the same ounce of gold was worth 372,477 marks. With the strike and increased printing of paper money, Germans needed nearly 270 million marks to purchase an ounce of gold by September, and the inflation rapidly got worse. By the end of November, 87 trillion marks would buy an ounce of gold. And of course, gold was not the only commodity that was becoming unaffordable in terms of marks. Stories circulated of people taking wheelbarrows full of Deutschmarks to the marked to buy a loaf of bread.

The disruption to the German economy was severe. As typically happens with hyperinflation, when workers received their pay they would rush to markets and immediately buy everything they could before the currency was worth any less. Workers demanded higher wages to keep up with higher prices, which only added more worthless currency to the money supply and created more inflation. The savings of middle-class families, set aside for a house, a car, or for retirement, were wiped out to purchase food for a week. Adding to the financial chaos, previous debts were quickly paid off with the now-worthless marks.

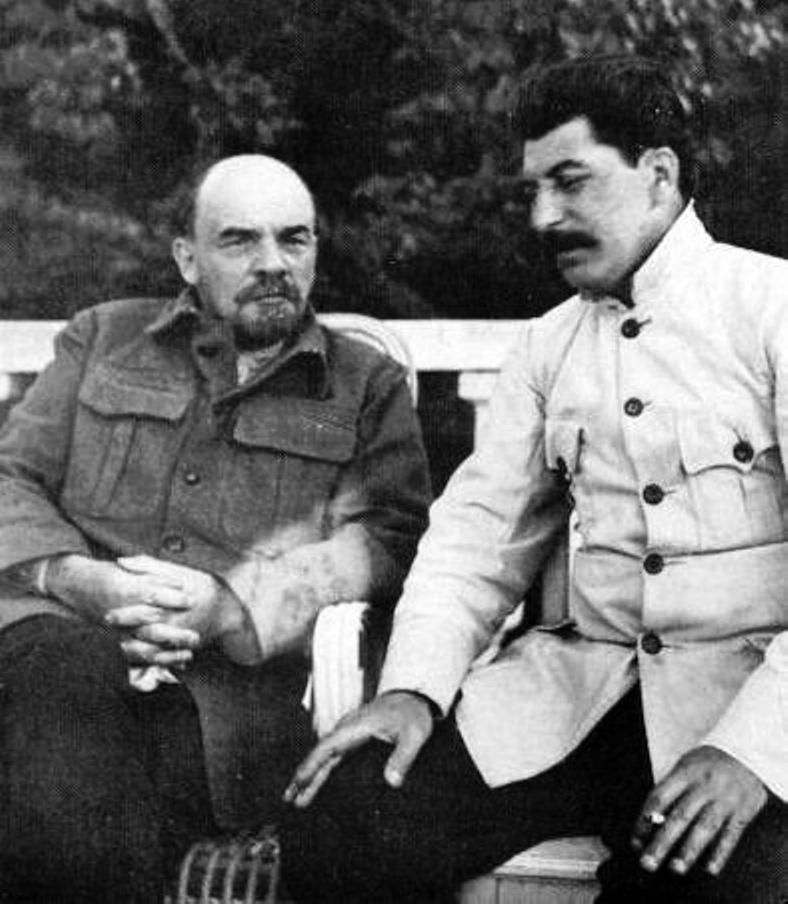

The Soviet Union

After its victory over the counterrevolutionary White Army, the Communists began establishing their version of the workers’ state envisioned by Marx in the new Soviet Union. A successful socialist revolution in Russia inspired dedicated Marxists around the world, prompting general strikes and attempted workers’ uprisings in Europe and even in the United States. However, Lenin’s tactics divided the revolutionaries from the reformers in the international socialist movement. Marx had predicted that the first step towards the socialist state was the establishment of a liberal democracy and an industrial economy filled with wage-workers (the proletariat). Russia had barely begun moving toward democracy and had very few industries when Lenin and Bolsheviks overthrew the government. Did this mean that in more developed democracies, dedicated socialists should embrace communism and foment an immediate revolution? Many believed Russia was an exception, and even Lenin struggled to fit events in the new Soviet Union into the outline of future history that Marx had provided. Part of the Communists’ focus on fomenting revolution in Germany was based on a belief that industrialized nations were more natural settings for these types of advances in the cause of a worldwide workers’ paradise.

Lenin suffered a stroke and died in 1923. Factions dividing the Soviet Communists formed around Leon Trotsky, Lenin’s close ally during the revolution and the successful commander of the Red Army, and Joseph Stalin, an extremely capable organizer who controlled much of the Party machinery. Trotsky argued in favor of a “permanent revolution,” constantly perfecting the workers’ state, which including eliminating private property in the countryside and collectivizing the agricultural sector. Stalin insisted that Lenin had already established a precedent by allowing a degree of market orientation in farming and that it seemed to be working well. Stalin won the argument and became the new leader of the Soviet Union. Trotsky went into exile, where he and his followers founded yet another Trotskyist International of like-minded revolutionaries. He was assassinated in 1940 in Mexico City, by a Soviet agent.

Stalin, in the meantime, announced the first in a series of Five-Year plans to industrialize the Soviet Union even more rapidly. In his second plan, he embraced the forced collectivization of agriculture. Stalin essentially came around to Trotsky’s view that small land-holders would become bourgeois anti-revolutionaries. Stalin was becoming increasingly paranoid of any social sector or group of leaders that he thought threatened his own authority, including his hold over the Communist cadre, the Comintern, and the apparatus of the Soviet bureaucracy. The forced collectivization of agriculture in the early 1930s led to death by starvation of nearly three million Ukrainians. Peasants resisted the loss of their land by planting and harvesting fewer crops and by killing their livestock before they could be seized. Many peasants were punished by the authorities, who confiscated everything they had and left them to starve. By 1931 when Stalin announced to the world that the wildly successful five-year plan had been completed ahead of schedule, at least 3 million peasants had died. The famine is known in Ukraine as Holodomor, or the Ukranian Genocide.

As the claims made by Stalin diverged more and more from reality, dissenters had to be dealt with. Stalin began sending critics to Gulag concentration camps in Siberia, or simply having them executed by his secret police. In the late 1930s, about 1.7 million suspected dissenters were arrested and 724,000 people were shot in the back of the head by Russian secret police. Among these were hundreds from the Red Army officer corps, who Stalin suspected were sympathetic to the ideas of Trotsky. Stalin wiped out an entire generation of seasoned military leaders who had helped the Bolsheviks achieve their power.

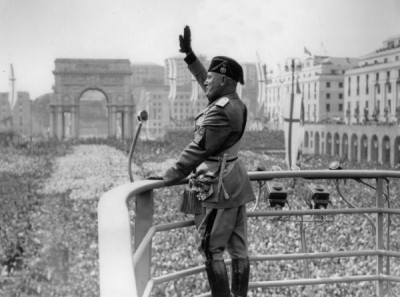

Rise of Fascism

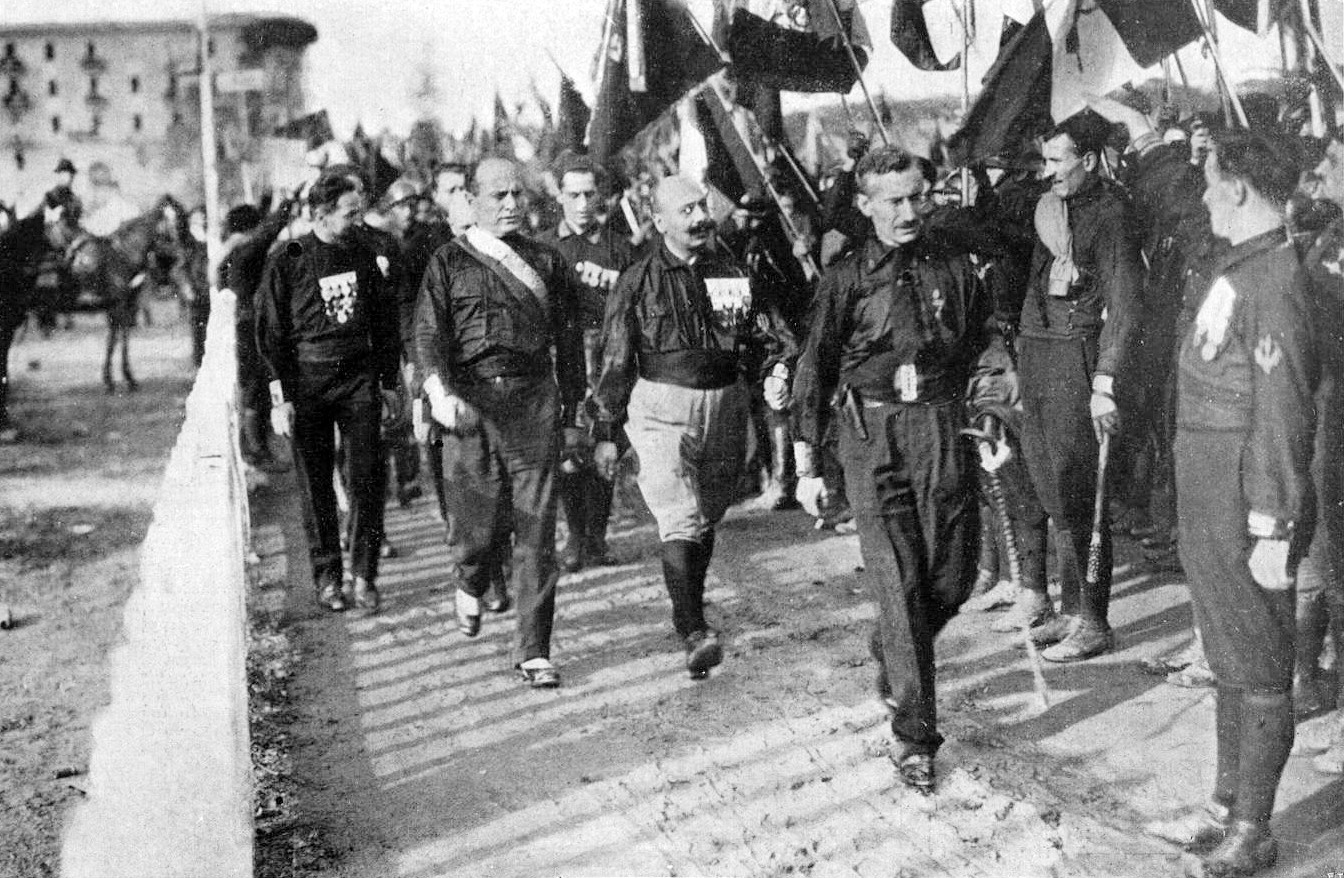

Like other European countries, Italy was disrupted by labor and socialist agitation after World War One. Strikes in the industrial north and agitation by landless peasants in the agrarian south were suppressed only with great difficulty by the government, a multi-party parliamentary democracy with a figurehead king. Since the 1870s, constant shifting of political coalitions, cabinets, and prime ministers had resulted in governments that were barely ready for war—the Italians had little to show for the nearly 750,000 dead soldiers who fought the Austro-Hungarians to a draw in the Alps. The government was even less prepared for what seemed to be an imminent Red revolution. In October 1922, in the midst of yet another general strike, the Fascist Party, led by Benito Mussolini, marched on Rome. To prevent civil war, the King asked Mussolini to form a government. He would remain prime minister for the next twenty years.

Mussolini had begun his political career as a revolutionary socialist before World War I. However, he despised the pacifism of Italian socialism and became a convinced nationalist. He served in the war; like Germany’s Adolf Hitler, reaching the rank of corporal. Shortly after the war’s conclusion, he reentered politics, trading his previous socialism for a militarist nationalism in a new Fascist Party.

In addition to being anti-socialist, Fascism was anti-liberal and anti-democratic. Mussolini and his followers believed that parliaments were ineffective talk-fests of corrupt politicians that should be replaced by strong authoritarian leaders. Although fascists in Italy and the rest of Europe participated in elections, they did so with a high level of organized street violence by their own paramilitary units against political opponents, especially socialists and communists. Mussolini’s black-shirted squadristi were imitated by the Nazi brownshirts in Germany and the Falangist blue-shirts in Spain, among many others in the rest of Europe and the Americas. Not only did they break up rival political meetings, they also brutally attacked strikers and labor organizers.

By 1925, Mussolini had outlawed all other political parties and declared himself the supreme leader: Il Duce, in Italian. He went on to impose “totalitarianism”, his word for state control over the entire social and economic life of the nation. Claiming that they were protecting private property against socialism, fascists actually created a form of state corporatism that was every bit as autocratic as Stalin’s system but retained the appearance of private ownership. “Corporations” in this case means not only industrial companies, but also “corporate groups” of citizens based on their occupations, guilds, and associations. The leaders of these corporate groups represented their members in the national government, under “coordination” by the dictator. The establishment of corporate groups supported the claim that a wide array of political parties was no longer necessary; but in reality, the selection of leaders was limited to members of the official state party.

Mussolini and other fascists wanted to impose upon their countries military discipline and unquestioning loyalty to the leader. Imperial expansion became a priority and war was encouraged to bring grandeur to the nation and strengthen its people. Fascists promoted a mythic past of glorious conquest to inspire a warrior culture. Mussolini wanted to build a large army and navy to dominate the Mediterranean and to expand the Italian Empire—all to “make Italy great again.”

Fascism gained ground more slowly in most other countries in the 1920s, until the onset of the Great Depression. Italy did not seem to suffer as acutely from the social, labor and political unrest that came with the unexpected international economic crisis because the Italian opposition had been eliminated or jailed years before. For property-owners and capitalists, fascism was a defense against revolutionary communism, while even for some in the working class, it seemed to provide a degree of social and political stability that democracy was struggling to retain. This impression, even if it was not entirely accurate, did a lot to interest Italy’s neighbors in a political system that “made the trains run on time.”

The Great Depression

The exact causes of the Great Depression are still being argued by historians and economists. An ongoing agricultural recession in the United States and abroad during the 1920s was an important element, as was a Wall Street stock market bubble caused by excessive use of margin to buy company shares. Investors were able to buy the shares of companies for pennies on the dollar by borrowing 90% to 97% of the purchase price. This allowed them to buy ten to twenty times the number of shares they could actually afford, with lenders putting up the rest. This system works very well as long as prices continue to rise, and the extreme demand for stocks powered by margin-buying drove the prices ever higher. Insider trading was also quite common, with secret “pools” of investors buying up stocks to inflate prices, waiting for others to join in the game, and then selling when the price reached a profitable new height. During the 1920s, the value of the stock market doubled without a corresponding increase in corporation assets or earnings. The market grew at a rate of over 20% per year while the economy shrank. Most stock prices rose to levels that could not be explained by their assets or earnings, since industry was actually starting to feel the pinch of the agricultural recession. Stock prices typically reflect the underlying value of the company; in the bubble they mostly reflected the buying frenzy. When credit became a bit tighter and people began receiving margin calls and trying to sell more of these inflated shares than there were new buyers for, the bubble burst.

Black Thursday was October 24, 1929. But it was only the beginning of a series of economic calamities. The Dow Jones Industrial Average (the most popular average of the value of America’s largest stocks) had fallen nearly 5% the day before, and opened Black Thursday at 305. As soon as the opening bell rang, the market began dropping fast on volume three times greater than normal. The three major banks, Morgan, Chase, and National City, began buying heavily to try to stabilize the market, and the Dow recovered a bit, ending the day at 299. On Friday, the market closed a bit higher, but the following Monday the average dropped to 260 which triggered another round of heavy panic selling on Black Tuesday, when the Dow dropped to 230. After this weeklong crash, the market continued sliding for the next three years. The Dow average finally bottomed out at 41. The market lost 90% of its pre-Crash value, and would not reach the levels it had seen in September 1929 for another 25 years until 1954.

The sudden evaporation of the market, even though the prices of stocks had been ridiculously inflated, resulted in a collapse of lending. Loan amounts had been based on these inflated asset values; the values had disappeared but the debt remained. Companies stopped producing products and laid off workers. Families lost their life savings and their jobs at the same time. After foreclosing on bankrupt farmers, rural banks were stuck with farms whose worth continued to drop. Rural banks began to fail: they had lent the money of their depositors to farmers who could not pay them back. “Runs” on banks everywhere became more frequent as anxious depositors rushed to take out their cash. Smaller banks had also borrowed from larger banks, affecting the entire financial system. Wall Street stopped lending money to Germany to pay its reparations to the Allies.

Worldwide, the cost of food and industrial goods dropped considerably as businesses sought to lessen the effect of losses. But unemployment was so staggering that few farmers and workers had enough to pay for anything, even at rock-bottom prices. Governments embraced protectionist high tariffs in a last-ditch effort to stimulate domestic industry; however, this led to a collapse of global free trade which hurt the world economy even more.

In their desperation, people everywhere began to question the effectiveness of capitalism and liberal democracy to resolve the crisis—indeed, many began to blame liberalism and market capitalism for their sudden impoverishment. Many saw the Soviet Union as a new model for economic stability, especially because Stalin was claiming the success of his Five Year Plans and no one knew what was going on behind the scenes. There seemed to be no unemployment under the Communists. Some who felt threatened by revolutionary communism embraced fascism. Although labor unrest and mass protests broke out all over, Mussolini seemed to be maintaining order in Italy. Also, fascists did not seek to end capitalism and private property like the communists promised to do. Many in the middle class supported new fascist-inspired governments as a better guarantee of their livelihoods than the liberal democracy that seemed to have failed them. This is essentially the story of how a minor political figure, Adolf Hitler, was able to become Chancellor of Germany in January 1933.

The Nazis

In the 1920s, Germans had elected moderate, social democratic governments. The disruption caused by the collapse of Wall Street and world trade especially affected German industry. Loans and markets dried up, and millions of employees lost their jobs. Hyperinflation wiped out people’s life savings. Previously, communists and (especially) National Socialists (Nazis—German fascists) had been fringe parties, easily ignored. But as Germans became increasingly desperate, they looked for easy solutions, or at least someone to blame for the crisis of world capitalism. Political conflicts took to the streets, with social democrats fighting communists and both groups fighting Nazis. Government instability led to frequent elections; the moderates coalesced around chancellor Heinrich Bruning, a conservative of the Catholic Center Party, who was positively Hooverish in his tight-fisted social and economic policies. In the 1932 elections, no party won a clear majority (which was not unusual), but for the first time, most German voters backed either the Communists or the Nazis.

Meanwhile, intrigues began swirling around President Otto von Hindenberg, who (like a king in a parliamentary monarchy) was responsible for choosing a politician to take the role of Chancellor and form a government. The octogenarian Hindenburg took the advice of aristocratic nationalists in January 1933 to call upon Adolf Hitler, leader of the Nazi Party, to form a government. The aristocrats believed Hitler could be controlled; he had other ideas.

Hitler and the Nazis were like the Italian Fascists in their anti-liberal, anti-democratic, hyper-nationalist ideology, and support of the totalitarian ideal for ruling their nation. They even had their own paramilitary force with uniforms and insignia, and a powerful symbol in the swastika. The Nazis also appealed to many voters because of their consistent opposition to the Versailles Treaty, which nearly all Germans blamed for their economic distress. For the Nazis, the Versailles peace was a national humiliation and the real reason that Germans were unemployed. They blamed the liberals and social democrats who had signed the treaty for having “stabbed Germany in the back.”

As Hitler took control, new elections were called for March 1933. During the campaign, the Reichstag building was burned down by a disgruntled communist; Hitler used this incident to arrest Communist politicians. Although once again the Nazis failed to win a majority in the election, Hitler was granted near-dictatorial powers. He outlawed the Communist Party and then the Social Democratic Party. By the end of the year, all other parties were outlawed or dissolved; by mid-1934, Hitler purged his own party of “left-Nazis,” eliminating all organized opposition. He was declared the leader (Führer) of Germany. Hindenberg’s death the following year allowed Hitler to combine the offices of President and Chancellor, so that the democratic Weimar constitution was a completely dead letter.

This was a remarkable achievement for Hitler, who until World War I had been a frustrated Austrian artist living in Vienna, absorbing extremist German nationalist and anti-Semitic ideologies. He had joined the German army at the beginning of the war; after the armistice, he was assigned by the army to observe and report on the various political groups that were appearing in Munich. Instead, he joined one of them, the National Socialist German Workers Party, and quickly became an effective speaker and leader. In 1920, he adopted the ancient Hindu swastika symbol in his design for the party’s flag. After an attempted coup failed in Munich, Hitler was imprisoned in 1923. While in prison, he wrote Mein Kampf (My Struggle) an outline of his plan for the domination of the pure German “Aryan race” over Europe. Hitler’s anti-Semitism blended with his hatred of “foreign” Bolshevism, and he imagined German “Aryans” as Europe’s defense against Jews and socialism. Nazi focus on racial hatred set them apart from the Fascists in Italy, although anti-Semitic ideas were shared by other nationalists and fascists in Europe.

Hitler and the Nazis, like the Fascists in Italy, built their power by appealing to people’s worst prejudices and to their feelings of resentment that their problems were someone else’s fault. Jews were always a convenient scapegoat. As a group, they were perceived as being more successful in academia, the professions, and business than their Christian counterparts. Close study of scripture was respected and encouraged, and these habits were quickly applied to careers in law, medicine and science once Jews were liberated from the ghettos. Although they continued to face discrimination, Jews seemed to have benefited more from industrialization and “modernity” than most of the working-class and lower-middle class farmers, factory-workers, and displaced white-collar workers who would become the base for the Nazis and other fascist parties. It was easy to blame Jews for the economic and social problems facing Europe in the 1930s, especially since they were believed by many to not fully be part of the “nation,” but rather a separate international community that divided their loyalty away from the fatherland. Incongruently, the Nazis claimed that Jews were behind both Communism and the international banking and financial system that Communists wanted to destroy–a Jewish cabal was supposedly fomenting every crisis in a complex (and nonsensical) conspiracy theory.

Still, in the mid-1930s, Hitler’s popularity in Germany was not initially based on Nazi racism. Instead, Germans appreciated the political, social, and economic stability the regime brought, and the ways Hitler was thumbing his nose at the Versailles Treaty. The Nazis suppressed labor unions, but work projects like building the Autobahn superhighway put men back to work. Hitler called for an affordable “people’s car”, and in 1937 his government built a state-owned factory to manufacture a design created by race-car designer, Ferdinand Porsche. The original Volksauto (renamed Volkswagen) would be available to German citizens for $396 through a government-sponsored savings plan. Rebuilding the military also provided jobs and opportunities. Hitler expanded the army well beyond the 100,000-man limit set by the treaty, and added air and submarine forces in further violation. In early 1936, when he moved troops to the French border, the Allies did not respond militarily; much to the surprise of many German generals. Berlin successfully hosted the Olympics in July 1936, showcasing the regime to the world while also starting the tradition of lighting an Olympic flame brought from Greece by relay runners. Germans felt pride that Hitler had “made them great again.”

German Jews, however, suffered under the regime. Almost immediately after Hitler became chancellor, the Nazis called for a boycott of Jewish-owned businesses and Jews were fired from government positions. The 1935 Nuremberg Laws prohibited marriage with Jews and defined Jewishness based on ancestors. Many Nazified German towns “encouraged” Jews to leave so that they could put up signs declaring that they were “Jew-free”. A trickle of German Jews were able to emigrate: artists, actors, and film directors moved to Hollywood, while academics like Albert Einstein found positions in U.S. universities. But most of Europe and the world did not accept Jewish immigrants. Anti-Semitism was an international problem: although it was not as violent and discriminatory as the Nazi regime, even in the United States Jews were subjected to quotas at universities, were not allowed to buy houses in certain neighborhoods, were denied service at hotels and resorts, and were not accepted in many private clubs and associations.

China, Japan, India

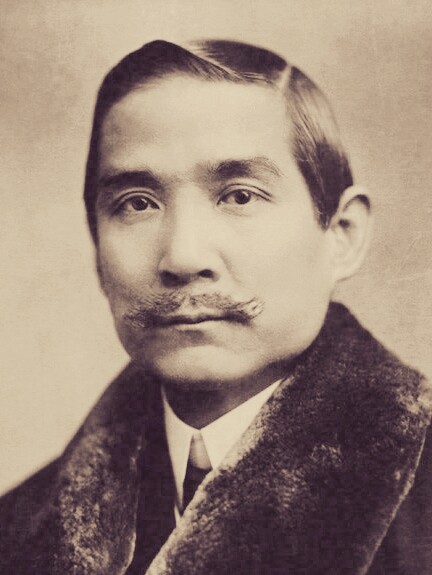

In 1911, Sun Yat-sen and his Xinhai Revolution finally overthrew the empire that had ruled China for over two thousand years, but the revolutionaries were not strong enough to install an effective government throughout China. Warlords (army generals and minor regional nobility) quickly organized troops to bring order to the countryside. However, they were not interested in respecting or supporting the new republic, which was seen as a European novelty. In the power struggle between Sun Yat-sen and General Yuan Shih-kai, the head of the Imperial Army, Yuan won. Instead of Sun Yat-Sen, a warlord became president of the republic under the new constitution. In the chaos of the republic’s early years, remote imperial provinces were able to establish their own nations, separate from China. Mongolia is still independent, while Tibet was reconquered by Mao Zedong in the 1950s and is still seeking independence.

After Yuan’s death in 1916, cliques and civil conflict broke out between the republic and the warlords. Yuan had declared himself emperor in 1915, and additional provinces had broken away in protest. Sun and the nationalists experienced a resurgence on May 4, 1919, when students revolted in Beijing against the Versailles Treaty, in which Japan received the German protectorates in Shandong province, rather than China. These demonstrations marked an important modernizing moment for the new Republic. Later that year, Sun Yat-sen formed the Kuomintang (Nationalist) Party, inspired by the May 4th Movement. By 1921, Sun had reestablished the republic in Canton. Meanwhile, western-educated intellectuals had begun organizing the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in Shanghai, supporting Sun and the Kuomintang against the warlords.

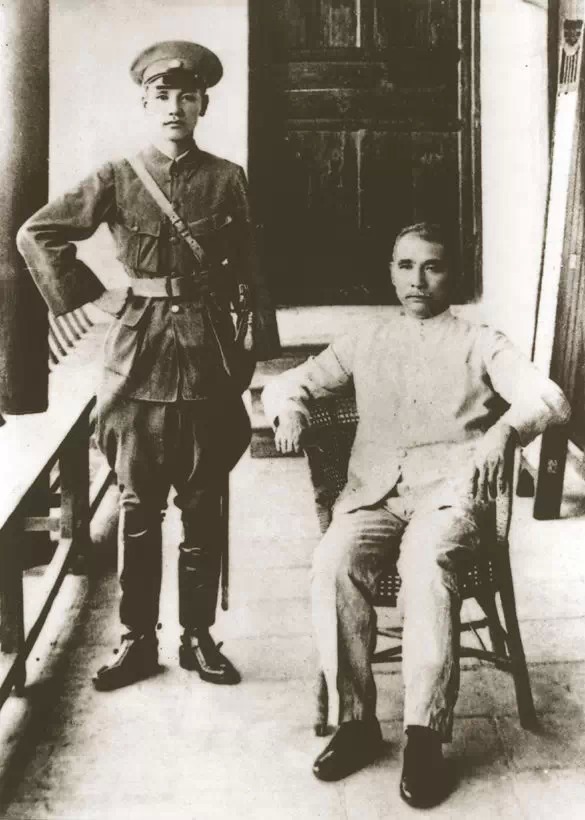

As the struggle continued against the northern warlords, Sun died of cancer in 1925, and his protege, General Chiang Kai-shek took over the Kuomintang. Chiang was a capable leader who was able to unite the government. In 1927, Chiang married U.S.-educated Soong Mei-ling, the sister of Sun’s widow Soong Ching-ling. By 1927, the “Northern Expedition” against the warlords was successful, led by Chiang with CCP and Soviet support.

A few months later, however, a new civil war began in China. Chiang turned against his communist allies, who he feared were strengthening their support in the cities. Chiang purged CCP-members from the Kuomintang, and beginning in the commercial and financial capital in Shanghai, began rounding up and executing many Communist leaders, while imprisoning others. In 1931, the Japanese military invaded Manchuria and created the puppet Kingdom of Manchukuo, installing the heir to the Qing dynasty, Pu Yi, as the monarch. The Chinese Republic, in the midst of a new civil war, was not in a position to fight the Japanese.

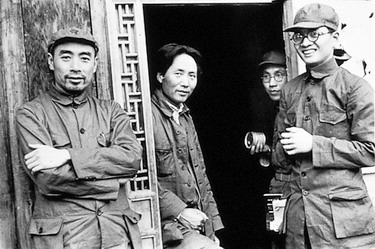

With so many communists imprisoned or executed, Mao Zedong, a charismatic leader of peasant origin, rose to prominence in the Chinese Communist Party by the early 1930s. The Nationalist armies reconquered parts of China’s interior under Communist control, surrounding the communists in the Jiangxi Province in October 1934. The CCP forces broke out of the trap and began what became known as the Long March. In 370 days, the communists covered 5,600 miles including some of the most rugged terrain in china. Mao Zedong gradually emerged as a leader of the CCP, along with Red Army leader Zhou Enlai. Zhou would become the first Premier of the Peoples Republic of China and Mao would become the Chairman of the CCP.

As seen in previous chapters, by embracing western technology and government, Japan went in the opposite direction of China in the late 19th and early 20th century. By 1910 the Japanese Empire had extended its territory to include the Ryuku Islands and Taiwan, had defeated the Russians in the 1905 war, and had taken control of the Korean peninsula. Japanese industrial goods, especially textiles, found markets in the U.S. and other parts of the world. And as part of the victorious Allied coalition in the Great War, the Japanese were awarded the Marshall Islands and Shandong peninsula from Germany, although their proposal to condemn racism was not approved by the Allied diplomats in Paris.

Japan enjoyed a parliamentary monarchy, with political parties, trade unions, a parliament, and a “divine” emperor. In international affairs, the civilian government joined the World War I allies in an effort to decrease the militarization of the Pacific and East Asia and agreed to maintaining a smaller navy in the Pacific than either the U.S. or Great Britain in the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty. Increasingly ultra-nationalist officers in the army and navy were upset with the civilian government for negotiating the treaty. They advocated a Japan that would dominate East Asia, eventually replacing European rule and influence. “Asia for the Asians” was a motto they would use as they turned their attention to more regions that needed “liberating”.

As the reign of the new Emperor Hirohito began in 1926, the nationalist resurgence continued in the military, taking over Japanese foreign policy at the beginning of the Great Depression. The protectionism of many countries in the wake of the international financial crisis harmed the export-dependent Japanese economy. Ultra-nationalists in the military began advocating an extension of the Japanese Empire, following the example of the British in India. In 1931, an “incident” was staged by Japanese forces in Manchuria, giving Japan an excuse to take the region Manchuria from China. The civilian Japanese government was not in a position to reverse the conquest of Manchuria by their own military. Japanese diplomats ended up defending the takeover at the League of Nations.

In the following years, the nationalists gradually took control of the Japanese government, using the same anti-democratic, anti-Bolshevik rhetoric as the European fascists. In late 1936, Japan united with Germany in an Anti-Comintern Treaty in opposition to the Soviet Union and communism. The ideology of Japanese militarists similar to the Nazis in its racism: they believed that it was the destiny of the “Yamato” people to dominate East Asia and replace the Europeans, just as Hitler claimed a similar mantle for his pure “Aryans” in Europe. The Japanese Empire would bring order and prosperity to an Asia, “for the Asians” through the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere. Japanese imperialism seemed like an attractive proposition to some in East Asia who wanted to rid themselves of European imperial rule.

As mentioned previously, the British trained and educated locals in India as soldiers, police, government administrators, and professionals in the nineteenth century in order to run the Empire, claiming they were preparing India for eventual self-rule. When the promised self-rule would begin became a source of debate and conflict between the colonizers and the colonized. In 1885, British-educated Indian reformers organized the Indian Congress Party to protest unfair treatment of Indians by British. They believed they were already administering the country and no longer needed British bureaucrats to tell them what to do. In 1909, British reforms provided for Indian representation in provincial legislatures, and as seen in the last chapter, Indian soldiers took part in many of the British campaigns during the Great War, especially in Africa and the Ottoman Empire. After the war, this service inspired increased agitation for independence.

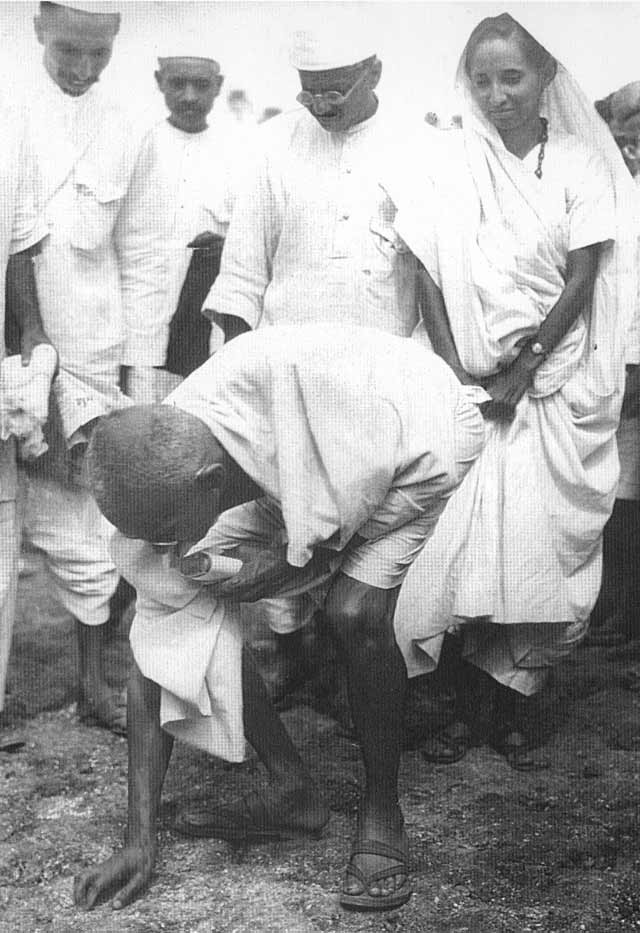

The politics of the Congress Party was greatly influenced by Mohandas Gandhi and his tactic of non-violent civil disobedience. Gandhi was a perfect example of the colonial serving the Empire: after being educated as a lawyer in England, he had lived in South Africa for twenty-five years, serving the growing Indian community there. However, reacting to racial discrimination, he began to organize on behalf of non-whites. Gandhi was already famous for his actions in South Africa when he returned to India in 1915, joined the Congress Party, and embraced asceticism and simplicity as a way of life. The following year, the mostly-Hindu Congress Party united with Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League in a sincere attempt to create a party that represented all of British India.

Popular calls for complete independence from Britain were accelerated by the horrific Amritsar Massacre in 1919, in which the British army killed hundreds of unarmed civilians. Increasing protests against British rule had led to oppressive measures, including the prohibition of public gatherings. In Amritsar, a religious celebration was interpreted as a political demonstration by the local British administrator, and he ordered his troops to open fire.

In the 1920s, the Congress Party organized the Non-Cooperation Movement, encouraging a boycott of British goods. Indian raw cotton was exported to Great Britain, where it was made into textiles that were sold back to the Indians. The Congress Party argued that factories could easily be built in India to serve the local market. By 1930, Congress Party leader Jawaharlal Nehru openly called for complete independence. The following year, Gandhi led his famous Salt March protest against the British salt monopoly. The British controlled the production and sale of salt, so Gandhi led a massive march to the sea to illegally make salt from the ocean. Non-violently disobeying an absurd law effectively highlighted the futility of Britain’s position in India.

The British Parliament responded with the Government of India Act in 1935, which established regional legislatures. Voting was arranged by religious and social categories, applying a “divide and conquer” method that the British had been using since the nineteenth century. Focusing Indians on their religious differences would have disastrous long-term results, down to today. Nevertheless, the more inclusive Congress Party started winning regional elections in 1937.

It is important to consider that at a time when totalitarian fascism and communism were on the rise in throughout much of the world, Gandhi and the All-India Congress Party presented the option of effective non-violent civil disobedience to achieve social goals. They were radically in favor of independence, but also encouraged democracy. The asceticism and simplicity of Gandhi was an example to be emulated, not a way of life imposed from above. Indian ideas and techniques would become an example for other struggles by colonized peoples and oppressed minorities, directly influencing the course of decolonization and the struggle for civil rights by African-Americans in the United States after World War Two.

Media Attributions

- EH 2723P

- 2880px-AlzadosEspartaquistas.

- Berlin, Reichsbank, Geldauflieferungsstelle

- Lenin_and_stalin_crop

- GolodomorKharkiv

- Benito_Mussolini_Roman_Salute

- March_on_Rome_1922_-_Mussolini

- Eritrean_Balilla

- Crowd_outside_nyse

- Adolf Hitler

- Hitlermusso2_edit

- Dr._Sun_in_London

- Sun_Yat-sen_and_Chiang_Kai-shek

- 1937_Mao_Zhou_Qin_in_Yan’an

- Emperor_Showa

- Manchukuo011

- 2560px-Mahatma-Gandhi,_studio,_1931

- Salt_March