12 Globalization

At its most basic, globalization refers to business activities and the actions of governments beginning to be conducted on a worldwide scale. As we’ve seen, this has been happening throughout the modern period we’ve been covering, if not before. The voyages of Zheng He, the European colonial project in the Americas, the Atlantic Slave Trade, and the activities of the British East India Company in India and China were all conducted at a worldwide scale, and all had commercial elements. Conflicts such as the Seven Years War, the War of 1812, and World Wars I and II have also involved multiple continents. And events like the Columbian Exchange, which made American staple crops available to feed growing world populations, and the “Spanish Flu” pandemic which killed up to 500 million people throughout the world, also had global consequences.

As we begin to look at the most recent wave of economic and political globalization, big commodities like petroleum become prominent again. Twentieth-century economic colonialism involving oil was not limited to the Persian Gulf. As we have seen, before Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia became leading producers, Mexico was a heavy supplier of oil to the US in the 1920s. In 1938, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas invoked the new, 1917 Mexican Constitution to nationalize all oil production in Mexico.

As we begin to look at the most recent wave of economic and political globalization, big commodities like petroleum become prominent again. Twentieth-century economic colonialism involving oil was not limited to the Persian Gulf. As we have seen, before Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia became leading producers, Mexico was a heavy supplier of oil to the US in the 1920s. In 1938, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas invoked the new, 1917 Mexican Constitution to nationalize all oil production in Mexico.

The constitution, which had been written during the Mexican Revolution, stated that the nation owned all the subsoil assets of Mexico, and Cárdenas formed the government-owned oil company PEMEX to extract and refine Mexican petroleum resources. Although the corporations (particularly Royal Dutch Shell and Standard Oil) objected loudly, Franklin Roosevelt’s administration, which was busy implementing the New Deal at home to ease the impact of the Great Depression on the American people, acknowledged the right of the Mexican people to control their own resources. Soon, the advent of World War II encouraged the Allied nations to put anti-fascist solidarity before the losses of a couple of U.S. corporations. PEMEX prospered and became Latin America’s second largest corporation in 2009 (after Petrobras, the Brazilian national oil company).

As I’ve mentioned earlier, development of Venezuela’s oil resources (thought to be at least 1/5th of known global reserves) began in the 1910s, when the country’s president granted concessions to his friends to explore, drill, and refine oil – and these concessions were quickly sold to foreign oil companies. In 1941 a reform government gained power which quickly passed the Hydrocarbons Law of 1943 which allowed the government to claim 50% of the profits of the oil industry. The outbreak of World War II increased demand for oil to such an extent that the government was able to grant several new concessions in spite of the 50% tax. The postwar explosion of automobile ownership in the U.S. continued to drive demand and push oil prices higher, and Venezuelan production increased. Venezuela bought the Cities Service company and CITGO gas became a key export of Venezuela. In 1976, the government nationalized the oil industry. Oil was a mixed blessing for Venezuela, providing high levels of revenue for the government but also preventing Venezuelan industry from diversifying. In recent decades, Venezuela used its oil revenue to pay for a wide range of social welfare programs for its people. The U.S. criticized these policies as socialist, but they were rarely done without widespread popular support in Venezuela. Hugo Chávez, who was president from 1998 to his death in 2013, criticized the U.S. government vehemently but also continued the Venezuelan policy of giving free heating oil to hundreds of thousands of poor people in the US and Europe.

After increasing during the Arab oil embargo of the 1970s and then peaking during Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan in the early 1980s, oil prices languished in the late 80s, exacerbating the Soviet Union’s economic problems. In the early 1990s after the Soviet breakup, Russia began exporting millions of barrels daily into the world market. The dissolution of the U.S.S.R. and the Warsaw Pact accelerated the globalization of commerce. Globalization in this new phase is characterized by increased foreign investment by transnational corporations, privatization of state enterprises, free movement of capital across national borders, and a reduction of tariffs that impede the movement of products. A wave of deregulation accompanied these changes, as nations competed to attract businesses that were suddenly free to locate themselves anywhere resources, labor, and environmental costs were lowest.

One of the important forces driving globalization has been the removal of protectionist trade policies around the world. This trend began in 1947 with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a free-trade agreement of 23 noncommunist nations. Over time, GATT reduced average tariff levels between member nations from 22% in 1947 to just 5% in 1999. The World Trade Organization (WTO) that followed GATT is a more permanent agreement that covers trade in services and intellectual property as well as physical products. The WTO, headquartered in Geneva, has 164 member states including, recently, China. Although the WTO’s charter calls on it to “ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably, and freely as possible” throughout the world, critics argue it favors rich nations over poor nations; especially in its binding arbitration processes that function like an international trade court, whose decisions take precedence over local or even national court judgments. Global corporations that can deploy teams of lawyers (or even station them permanently in Geneva) to argue in their interest seem to have a disproportionate influence on WTO decisions. The process is designed to take a year (or 15 months with appeals) and the WTO says that since 1995, over 500 disputes have been brought and 350 rulings have been issued. Most of these rulings have benefitted the transnational corporations, often at the expense of workers, consumers, and the environment.

One of the important forces driving globalization has been the removal of protectionist trade policies around the world. This trend began in 1947 with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a free-trade agreement of 23 noncommunist nations. Over time, GATT reduced average tariff levels between member nations from 22% in 1947 to just 5% in 1999. The World Trade Organization (WTO) that followed GATT is a more permanent agreement that covers trade in services and intellectual property as well as physical products. The WTO, headquartered in Geneva, has 164 member states including, recently, China. Although the WTO’s charter calls on it to “ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably, and freely as possible” throughout the world, critics argue it favors rich nations over poor nations; especially in its binding arbitration processes that function like an international trade court, whose decisions take precedence over local or even national court judgments. Global corporations that can deploy teams of lawyers (or even station them permanently in Geneva) to argue in their interest seem to have a disproportionate influence on WTO decisions. The process is designed to take a year (or 15 months with appeals) and the WTO says that since 1995, over 500 disputes have been brought and 350 rulings have been issued. Most of these rulings have benefitted the transnational corporations, often at the expense of workers, consumers, and the environment.

Transnational corporations are uniquely suited to take advantage of this new world economy. Technically there are about 50,000 global corporations, but the number of corporations that are as important as states in the world economy is a bit smaller. Fortune Magazine Global 500 of 2020 was topped by Walmart, Sinopec Group (a Beijing-based oil and gas company), State Grid (the Chinese national electric company), China National Petroleum (another Beijing-based oil and gas company), and Royal Dutch Shell Toyota. The next five on the list are Saudi Aramco (oil company), Volkswagen, BP, Amazon, and Toyota. Placement on this list is based on revenues, which is similar to the GDP used to measure the size of national economies. If Walmart was a nation, it would be larger than all but 23 of the 211 members of the United Nations.

Free trade and “laissez faire” capitalism are typically believed to be a “conservative” value, so some people have been surprised to see the recent Republican (Trump) administration opposing agreements like NAFTA and TPP and the Democrats (Clinton, Obama, Biden) supporting them. Globalist trade policies have often been called “neoliberal,” but this is another confusing term. The elements that make this ideology “Neo” are in many ways the opposite of liberalism. Since the Enlightenment in social and political thinking that preceded the American Revolution, “liberal” has referred to a focus on expanding the rights and liberties of regular people, often against the power of governments. Today the liberties being protected by neoliberalism are often those of corporations, which in many cases have gained so much power over the lives of regular people that they are a more immediate threat than governments.

NAFTA was an example of neoliberal policy that increased the liberty of corporations at the expense of people. In a 1992 presidential debate, billionaire Reform Party candidate Ross Perot argued:

“We have got to stop sending jobs overseas. It’s pretty simple: If you’re paying $12, $13, $14 an hour for factory workers and you can move your factory south of the border, pay a dollar an hour for labor,…have no health care—that’s the most expensive single element in making a car—have no environmental controls, no pollution controls and no retirement, and you don’t care about anything but making money, there will be a giant sucking sound going south.”

Perot went on to explain that although in the long run and from a global perspective, globalization makes economic sense, it was not necessarily good for America. He said,”when [Mexico’s] jobs come up from a dollar an hour to six dollars an hour, and ours go down to six dollars an hour, and then it’s leveled again. But in the meantime, you’ve wrecked the country with these kinds of deals.” Perot ultimately lost the election, and the winner, Bill Clinton, supported the North American Free Trade Agreement, which went into effect on January 1, 1994.

The aim of NAFTA was to create a free-trade zone in North America and eliminate tariff barriers that made American exports more expensive in Mexico and Mexican exports more expensive in the U.S. Among the results, Mexico has risen to the second largest market for U.S. agricultural products, especially meat. Mexico has also become a large consumer of U.S. corn which receives extensive subsidies from the U.S. government. Cheap American corn has impacted the ability of Mexican farmers to compete and has also impacted the biodiversity of maize, which you’ll remember was originally developed in Mexico. Indigenous varieties are threatened by the monoculture of U.S.-developed hybrids – and since corn is wind-pollenated, the indigenous varieties are in actual danger of being lost. The danger of losing the genetic diversity of Mexican maize is that monocultures are vulnerable – remember the Irish potato famine? A pest or disease that wiped out Monsanto’s GMO corn would be bad for the company, but it would become a global disaster if scientists had no other varieties they could use to produce a new, resistant hybrid. Corn is the leading staple crop in the world. Do we really want to put all our eggs in one basket?

The aim of NAFTA was to create a free-trade zone in North America and eliminate tariff barriers that made American exports more expensive in Mexico and Mexican exports more expensive in the U.S. Among the results, Mexico has risen to the second largest market for U.S. agricultural products, especially meat. Mexico has also become a large consumer of U.S. corn which receives extensive subsidies from the U.S. government. Cheap American corn has impacted the ability of Mexican farmers to compete and has also impacted the biodiversity of maize, which you’ll remember was originally developed in Mexico. Indigenous varieties are threatened by the monoculture of U.S.-developed hybrids – and since corn is wind-pollenated, the indigenous varieties are in actual danger of being lost. The danger of losing the genetic diversity of Mexican maize is that monocultures are vulnerable – remember the Irish potato famine? A pest or disease that wiped out Monsanto’s GMO corn would be bad for the company, but it would become a global disaster if scientists had no other varieties they could use to produce a new, resistant hybrid. Corn is the leading staple crop in the world. Do we really want to put all our eggs in one basket?

Although the proponents of NAFTA claimed and predicted that the trade agreement would benefit all three nations, about eleven months after the agreement went into effect, the Mexican economy melted down. In late 1994, after Mexican investors decided to put their now-mobile capital in more stable investments abroad, the Mexican government was forced to devalue its currency and implement painful deflationary and austerity programs in order to get a bailout from the IMF. The experts and pundits all agreed that NAFTA was not to blame, and for the most part, the press either ignored or misrepresented the Mexican financial crisis, which it nicknamed the Tequila Crisis.

Perhaps the greatest effect of NAFTA on Mexico has been the rise of Mexican factories called maquialadoras which were located just south of the border and made products for the US market. In the five years after NAFTA’s 1994 implementation, maquila employment nearly doubled. These factories in border towns adjacent to the U.S. manufacture goods using supplies shipped to them duty-free, which they then ship back north. By 2004, maquiladoras accounted for 54% of Mexico’s exports to the U.S., and U.S. exports had grown to 90% of Mexico’s total exports. The advantages for U.S. manufacturers were lower wages than the U.S. (in 2015 the Mexican hourly wage averaged $0.55) and fewer environmental and worker-safety regulations. Although Mexico has fairly strict labor laws, maquiladoras are immune and the majority of workers are young women who are less likely to organize. As low as the pay is, after the Mexican recession of the 1990s these jobs sometimes pay better than other available work for poor Mexicans. However, the gains in Mexican employment have been matched by losses in the U.S. As Perot had predicted, until wages for factory workers in Mexico rise substantially, workers in the United States will not be able to compete for these jobs. Despite the U.S. recession in the early 2000s and competition from other even lower-wage areas like Asia, there are still over 3,000 maquiladoras along the US-Mexican border.

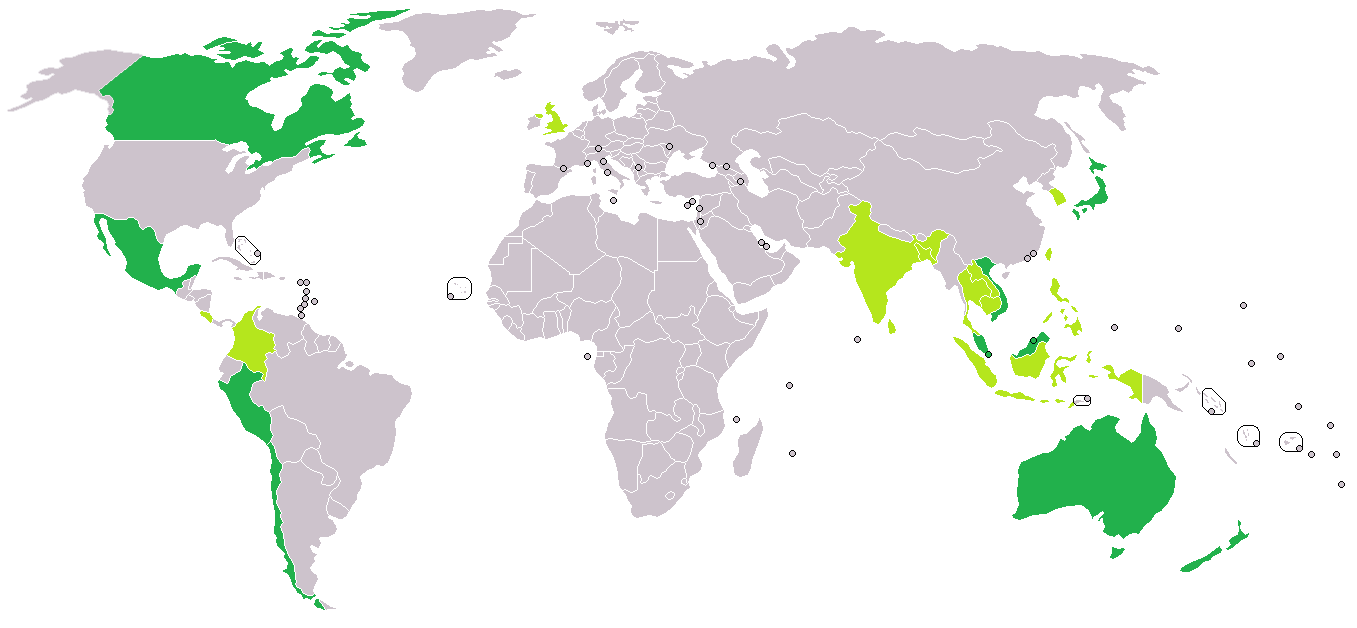

TPP, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, was designed to be NAFTA on steroids. TPP was established in 2016 to create a common market for countries bordering the Pacific. It sought to eliminate tariff and regulatory barriers to trade between most of the nations on the Pacific rim, to create a common market between Asia and the west coasts of North and South America. TPP would also to establish an Investor-state dispute system that would allow global corporations to sue countries for practices they deem to be discriminatory. This means that if a national government tries to set a national minimum wage, mandate worker rights or safety regulations, or protect the environment, corporations can sue to have the laws changed or can demand compensation for their “losses”.

Critics argue this raises the status of corporations to make them equal or even superior to sovereign nations, allowing them to sue in an “Investor Court” that would favor their interests over the rights of citizens passing laws to safeguard workers’ rights, the environment, or other local concerns that impact the global corporation’s profits. This is another way neoliberal policies subvert the democratic institutions created by the original liberalism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Ironically, NAFTA already includes an investor-state court system for the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, but since most of the companies that would use this system are U.S.-based, it is not seen as being an issue for Americans. TPP would be a much bigger source of lawsuits from transnational corporations not originally based in America and the U.S., which has higher minimum wages, worker safety standards, and environmental regulations, would probably be a target of many.

In 1999, protestors picketed meetings of the WTO in Seattle and in 2011 Occupy Wall Street protested wealth inequality in New York. President Trump’s move in January 2017 to withdraw the U.S. from TPP was applauded by Progressives like Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. In rare agreement with Trump, Sanders said, “For the last 30 years, we have had a series of trade deals…which have cost us millions of decent-paying jobs and caused a ‘race to the bottom’ which has lowered wages for American workers.” On the other hand, mainstream Republicans like Senator John McCain criticized what he called “a troubling signal of American disengagement in the Asia-Pacific region at a time when we can least afford it.” McCain’s concerns may have been genuine, but in the last five years of his life, McCain’s campaign committee and PAC raised and spent about $17 million dollars, mainly from corporations like General Electric and Pinnacle West Capital that had an interest in the success of TPP. The support shown by “centrists” of both political parties in the U.S., and the opposition of populists on the left and right wings of both parties, suggests a growing sense among regular people that both parties are under the control of their political donors, and no longer governing for the people.

An important element of the shift away from a U.S.-centered globalization is the growing economic power of Asia. Japan’s economy was jump-started after WWII by U.S. aid including a $2 billion direct investment and letting Japan off the hook for war reparations. Japanese goods were also given preferential access to U.S. consumer markets, so the Japanese economy focused on low-wage industries producing products for export to America. The United States no longer considered Japan a threat, but rather as a potential ally against communist China. The Japanese people, already quite accustomed to austerity, complied with their government’s new industrial policy and Japan reinvested its earnings and rapidly grew from a producer of cheap knock-off copies of American products to an innovator in high technology.

Other Asian nations like Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan followed in Japan’s footsteps in the 1960s and 70s, often also with aid from the U.S. designed to slow the spread of communism during the Cold War. After the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Deng Xiaoping gained power in 1978 and China began shifting toward a market economy in which the government would direct development with incentives rather than decrees and directives. In addition to a plentiful supply of cheap labor, China had high savings rates and Deng’s devaluation of the nation’s currency allowed Chinese savings and foreign exchange surpluses to be invested in securities like American government bonds. This made China the world’s bank, as nations like the U.S. fell deeper into debt. Finally, a rising standard of living in China has created a new middle class and a huge consumer market.

In 2002, ninety percent of the Chinese population lived in poverty, with seven percent listed as middle class, two percent upper-middle class, and one percent considered affluent by world standards. By 2012, the number of poor in China has been reduced to twenty-nine percent. Two thirds of the poor (nearly a billion people) have improved standards of living, in one of the most momentous shifts in world history. Fifty-four percent of Chinese in 2012 were considered middle class, and that fifty-four percent is expected to rise to upper-middle class status by 2022, with another twenty-two percent moving from poverty into the middle class, leaving only sixteen percent of Chinese people in poverty. This is nearly the same income demographic we see in nations like the U.S., which has a ten percent poverty rate. China is becoming a dominant force in the world economy once again, and the increased spending power of the Chinese people will soon drive the global market. Chinese demand for items like automobiles is expected to outpace the rest of the world for the foreseeable future. Companies like Foxconn, which began as a contract manufacturer of low-tech items like computer cases, has become a nearly $5 billion manufacturer of the highest tech items like Apple iPhones and computers. Lenovo, which began as a Hong Kong PC clone company in 1984, has been the world’s largest personal computer maker since 2013. Lenovo acquired IBM’s PC division in 2005, and the famous IBM ThinkPad became a Chinese product. Lenovo does about $45 billion in annual revenue and was the world’s largest cell-phone maker until 2016 when it was overtaken by Apple and Samsung.

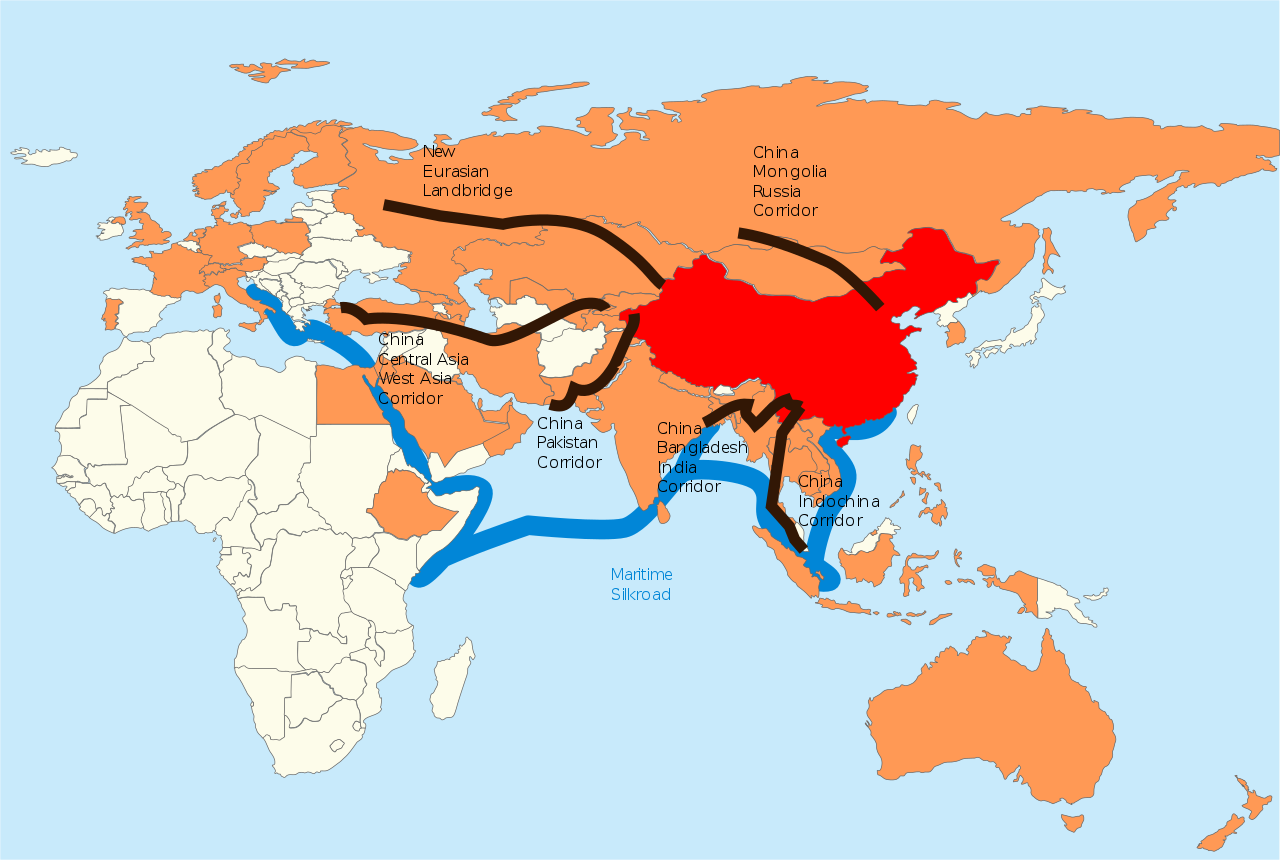

As Chinese purchasing power increases, world industry is will be challenged with producing consumer goods without exhausting finite resources or destroying the environment. Chinese cities have been known for their pollution, especially for their poor air quality. An increasingly affluent population may become less willing to tolerate environmental destruction, which might be a positive change. Hopefully, Chinese interest in projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative, which seeks to connect China with the rest of Asia, Europe, and Africa in a “New Silk Road”, will include a commitment to the environments of the places China finds its natural resources and markets for consumer goods, rather than the approach to hinterlands taken by earlier world economic powers, in which out of sight often meant out of mind.

The European Union grew out of a 1957 trade agreement that expanded on GATT to form the European Economic Community (EEC) including France, Belgium, West Germany, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Like NAFTA, the EEC reduced tariffs and other barriers to trade. In 1993, the European Union was formed including the original EEC members as well as Austria, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. In 1999, 16 member nations adopted a single currency, the Euro, although Sweden and the UK retained the Krone and the Pound Sterling. The English financial district called the City of London has always been a center of European banking and finance, and the British were desperate to protect the Pound against the German Deutschmark and the growing power of the Frankfurt-based European Central Bank. In the early 2000s several Eastern European nations joined, bringing membership up to 28 nations. Most of these new members adopted the Euro as well, and after the global financial crisis of 2007-8, the Eurozone established emergency loan procedures that allowed richer members to bail out the economies of poorer members in exchange for what the lenders termed economic reforms. Borrowers often viewed these reforms as a takeover of their economies and harsh austerity programs.

In June 2016 the United Kingdom held a referendum and in a shocking nationalist vote the majority decided to leave the European Union. Brexit is scheduled to go into effect at the end of March 2019. The residents of Scotland and Northern Ireland both voted to remain in the EU, but their votes were outweighed by the English and they will be forced to leave along with the rest of the UK. The Republic of Ireland will remain an EU member, which will complicate the situation on the border between Ireland and British Northern Ireland. The economic impact on Britain is difficult to calculate, but EU nations seem disinclined to allow Britain to retain the favored trade status it currently enjoys. And although many British people and politicians wished to reverse the decision to leave, the EU was unwilling to pretend the Brexit decision never happened. During 2020, an eleven-month transition period was agreed upon, to allow negotiators to establish post-Brexit policies. At the end of 2020, an agreement seems to have been reached that will allow the UK and the EU to continue trading without tariffs in 2021.

In addition to the increase in international trade, global culture has been permanently changed by communications technology. Computer networks and cell phones continued a process begun with the printing press, the telegraph, radio, and television. Each of these technologies has been used to spread ideas to wider audiences, often against the wishes of those in power. More recent inventions like fax machines, data communication via modems, the internet, and most recently smart phones and social networks have been used to spread news of events like the Tiananmen Square protests, the Arab Spring, and the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. In spite of the efforts of some nations like China and Saudi Arabia to censor media and limit internet access, it is increasingly difficult to firewall societies from the global media culture.

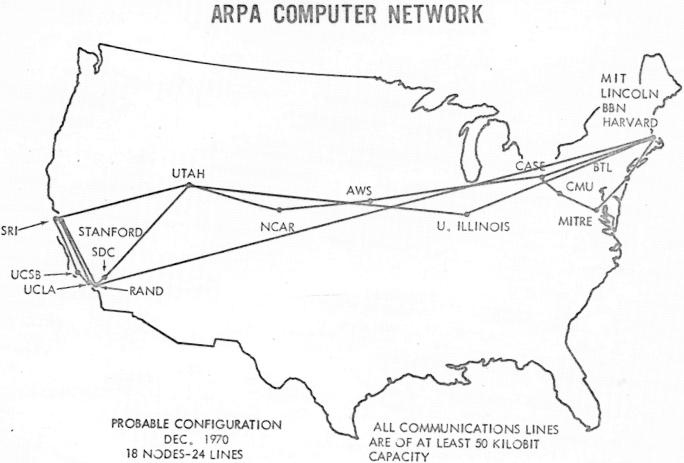

Because the virtual world is becoming as important to the global economy as the physical world of “bricks and mortar” commerce and communication, let’s take a moment to review the technological, government, and business changes that enabled it. One of the first computer networks was the semi-automatic business research environment (SABRE) launched by IBM in 1960, which initially connected two mainframe systems and grew into an airline reservation system. In 1963, American psychologist and computer scientist JCR Licklider proposed a concept he called the “Intergalactic Computer Network” when he became the first director of the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Licklider described it as “an electronic commons open to all, the main and essential medium of informational interaction for governments, institutions, corporations, and individuals.”

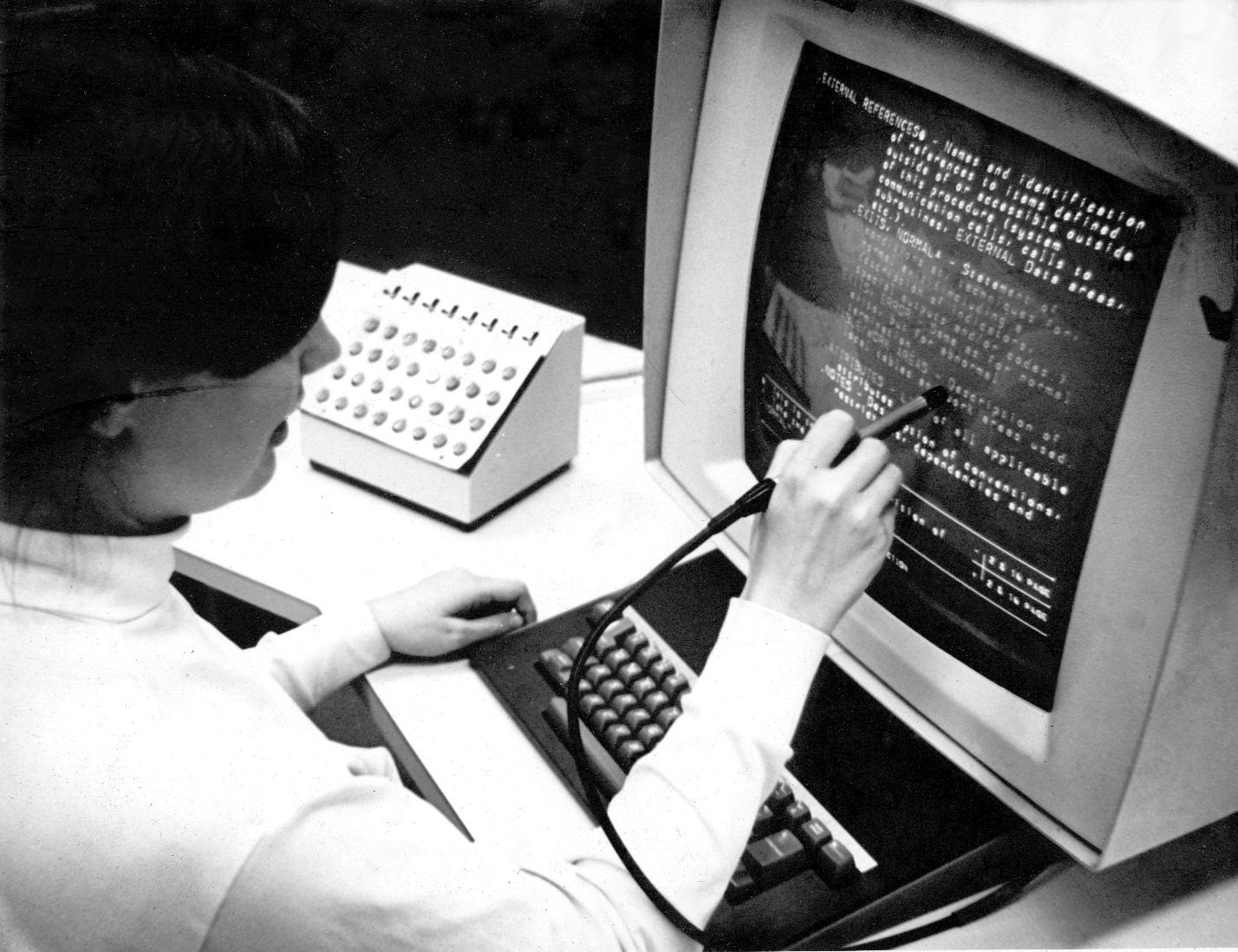

ARPANET, begun in 1969, was a network of networks, joining government facilities and research universities on a system dedicated to official communications. It was permissible for researchers and users to occasionally communicate personally with each other using email. Commercial and political communications, however, were strictly forbidden. A computer scientist named Ted Nelson developed the basic ideas that became hypertext and the web between 1965 and 1972. Nelson’s version of hypertext was based on the idea that there would be a “master” record of any document on the network. Exact copies of that document (which Nelson called transclusions in his 1980 book, Literary Machines) would point back to the original. Ideally, rather than just referring to the original, they would actually call up the original document wherever possible, eliminating the proliferation of copies.

This ideal was never really achieved, because even though storage was expensive, bandwidth was even scarcer. This is unfortunate, because the existence of bi-directional links would have allowed the owner of a document to know where and when it was used, and to have received compensation for its use. Two-way linkage was much more difficult to implement than a one-way hyperlink that launched the user to a new place on the web. Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak compared the two in a speech about Nelson in the 1990s, saying one-way linking was a cool hack, while two-way linking required computer science.

After the introduction of Apple Macintosh and IBM Personal Computers in the 1980s and the growth of online communication and file-sharing using services such as Compuserve and Prodigy in the early 1990s, in 1992, an online game provider called Quantum Link that had renamed itself America Online offered a Windows version of its free access software. AOL free trial CDs became ubiquitous; CEO Steve Case claimed that at one point in the 90s half the CDs produced worldwide had an AOL logo. By the mid-1990s, AOL had passed both Prodigy and CompuServe, and in 1997 more than half of all U.S. homes with internet access got it through AOL. The economic power of the online access was becoming apparent: in 1998 AOL acquired Netscape, in 1999 MapQuest, and in 2000 AOL merged with Time Warner.

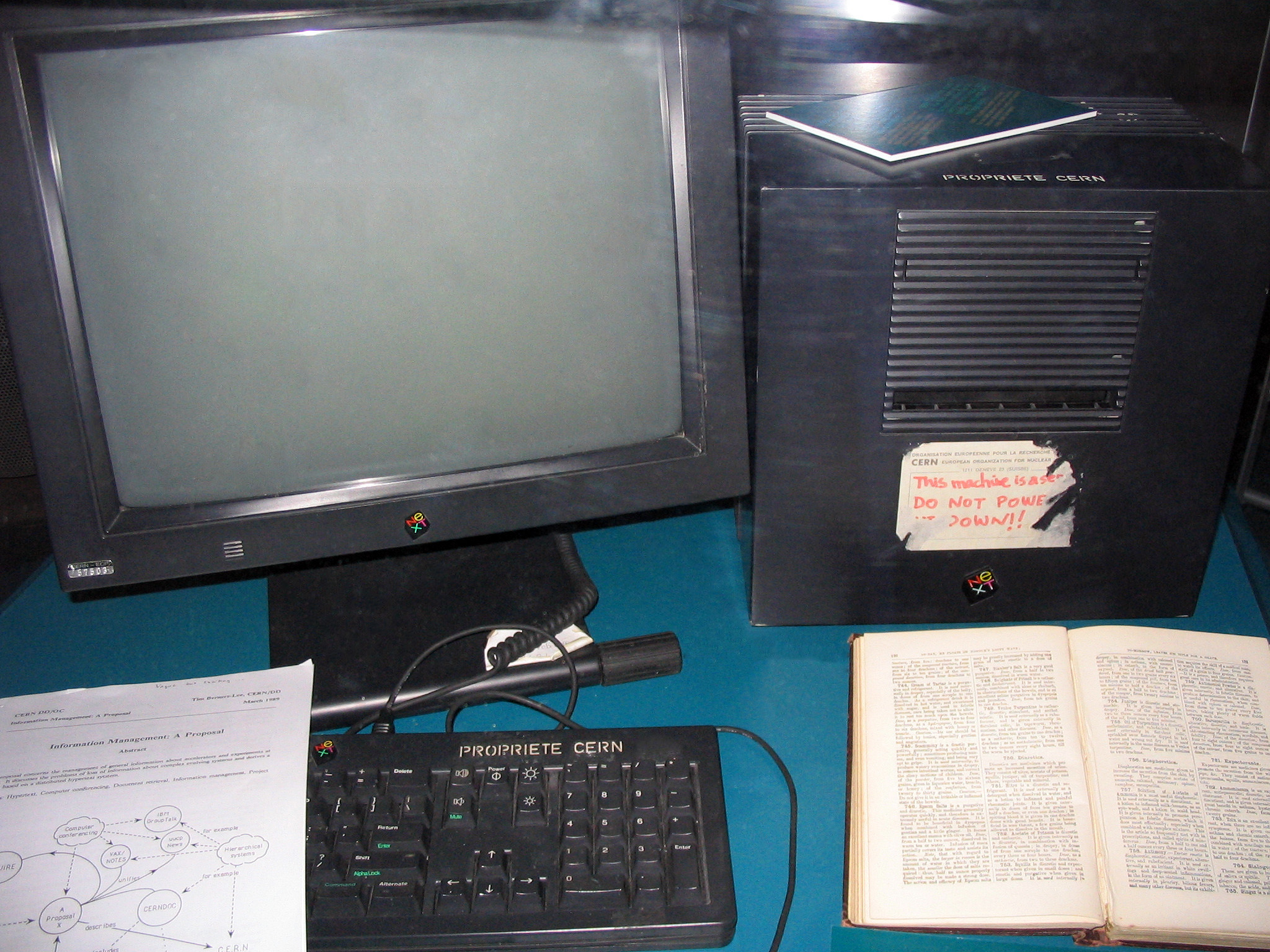

The commercial nature of subscriptions like AOL stood in sharp contrast, for a while, to the early internet. The inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, was a scientist at CERN in Switzerland when he wrote “Information Management: A Proposal” in March 1989. Somebody jotted on the front page of the paper, “Vague but exciting”, and Tim was given time to work out the details on a NeXT computer in his lab. By October 1990, Berners-Lee had written the three basic technologies of the web: HTML (Hypertext Markup Language), the formatting language of the web; URI (Uniform Resource Identifier, AKA URL), which contains the protocol (http, ftp, etc.), the domain name (example.com), and folder and file names (like /blogs/index); and HPPT (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), which allows retrieval of linked resources.

Being a government-funded research facility, CERN decided to make the protocols freely available, but it was the development of the MOSAIC browser by graduate student Marc Andreessen in 1993 that made Berners-Lee’s inventions the solid basis of the web. Andreessen graduated, moved to California and met Jim Clark, who had recently left Silicon Graphics. They formed Netscape and made their browser, called Navigator, available for free to non-commercial users. Netscape Navigator was destroyed by Microsoft’s decision to bundle its own browser, Internet Explorer, with Windows 95. Microsoft made it very difficult for PC manufacturers or even users to uninstall IE and use Netscape and Java, which led to an antitrust case in Feb 2001, in which the court ruled that Microsoft had abused its monopoly powers. Netscape never recovered from losing the “first browser war” however, and was acquired by AOL in 1999.

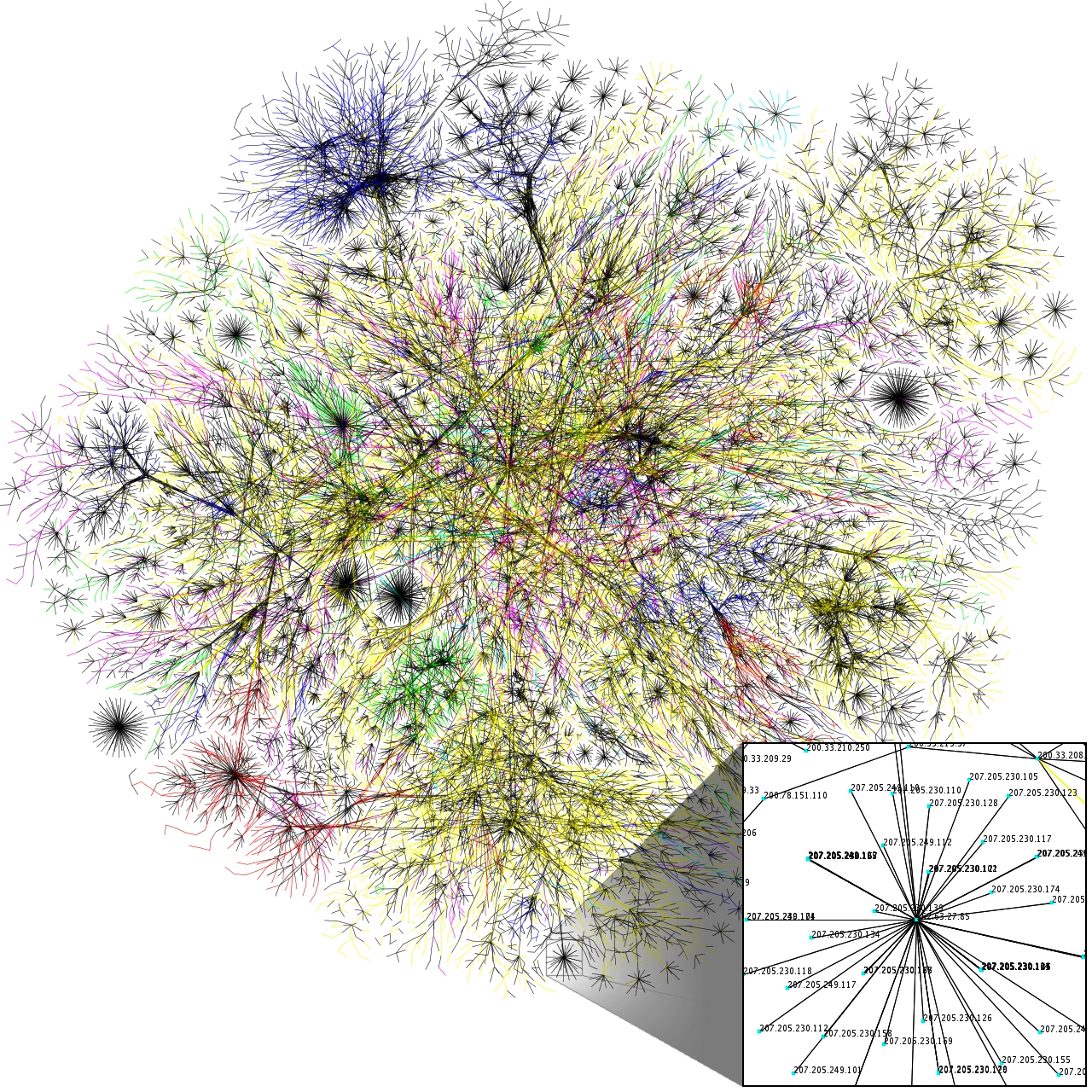

From 1991 (when there was only one at CERN) to 1994, when Yahoo launched, the number of websites rose to 2,738. The following year, when Altavista, Amazon, and AuctionWeb began, the number of websites had increased nearly tenfold to 23,500. In 1998, when Google launched, the number of websites had jumped tenfold again, to 2,410,000. The early years of the web, known as Web 1.0, were a period when people with modest skills could acquire a domain and build a website. One of the first powerful and intuitive apps for building websites and pages was Microsoft’s Frontpage. It was a Windows app that provided a WSIWYG design interface and output usable HTML code. Millions of people used the program to build personal and small commercial websites. Discontinued in 2003, Frontpage was not replaced by anything with similar power and ease of use. Partly this is because in Web 2.0 the do-it-yourself (DIY) element of the web has largely disappeared.

In 1999, a new generation of the web called Web 2.0 was announced, which claimed to focus on participation by users rather than people simply viewing content passively. One example of this participatory nature of the new web is the proliferation of social media. Another is people posting videos on YouTube. The web has also become a site of commerce though, so the most important instance of “participation” by web users is as consumers buying stuff – either web content like Netflix videos or iTunes music, or real-world goods on e-commerce sites like Amazon.

By 2001, when Wikipedia began, there were over a half billion internet users and over 29 million websites. There were a billion users in 2005, when YouTube and Reddit began, but growth had slowed to only 64,780,000 websites and a much larger percentage of them were commercial rather than personal. By 2010, when Pinterest and Instagram launched, there were 2 billion web users and the number of websites had actually declined from the previous year for the first time, to about 207,000.

In the 2010s the rest of the world caught up to the US in web use and website building. By 2015 there were well over 3 billion people using the web and by 2017 there were 1.7 billion websites. Since then the number of websites has decreased, dropping by nearly 10% per year. And about three quarters of these new websites aren’t active, but are parked domains or redirects. The actual number of sites in active use is probably closer to 200,000.

For people who wanted a presence on the web but didn’t have the skills or interest to own a domain or code a website, what some have called web 2.5 saw the beginning of social networking sites. The biggest of these from 2003 to 2008 was called Myspace. People could create a profile page, post images and multimedia, and see what their friends were up to. It was much less structured than what we’re used to today, allowing users a lot of flexibility to personalize their pages. Myspace was overtaken by a service, Facebook, that provided even more ease of use and uniformity. Facebook is extremely easy to use, which may be why it has recently become the place for grandparents to stalk millennials.

The final element in the story of computing and networks involves the battle between free, open resources and commerce, which we’ve already seen in the growth of the web. Operating systems in early mainframes and personal computers were tightly controlled by manufacturers like IBM, Digital Equipment Company, or Hewlett Packard, software businesses like Microsoft (DOS and Windows), and a number of workstation companies like Sun Microsystems and Silicon Graphics, which each owned a proprietary version of an operating system that had originally been developed by researchers at AT&T Bell Labs (which was prevented by an anti-trust ruling to get into computers) and the University of California, Berkeley. The Uniplexed Information and Computing Service, called UNIX, had originally been more or less open, but had become commercialized when AT&T sold its rights to a network software company, Novell, which later sold those rights to Santa Cruz Operation (SCO). In time, other organizations released versions which only ran on their hardware (and often cost thousands of dollars), including IBM (AIX), Microsoft (Xenix), Sun Microsystems (Solaris), SGI (IRIX) – all proprietary distributions with similar functionality.

In 1991, Finnish graduate student Linus Torvalds became frustrated with the high cost of UNIX. He wrote an operating system kernel in C, which he planned on calling Freax. Instead, early users called it Linux. The open-source operating system rapidly gained popularity among hackers due to its free distribution and its easy configurability. A programmer could configure the Linux kernel with just the features desired, which led to an explosion of both OS distributions (Red Hat, Debian, Ubuntu, Darwin, Android) as well as uses in embedded systems which were becoming popular. PC manufacturers like IBM and Dell adopted Linux as an option to reduce the cost of their systems and break Microsoft’s monopoly on the OS. Linux became especially popular for running file servers and internet routers, replacing expensive proprietary systems like IRIX, Microsoft NT, and Cisco. And organizations like NASA discovered that clusters of networked off-the-shelf PCs running Linux could rival the computing power of proprietary supercomputers. Companies like Sun and SGI found the markets for their workstations and servers disappearing overnight. Currently all the systems on the Top-500 supercomputer list run Linux.

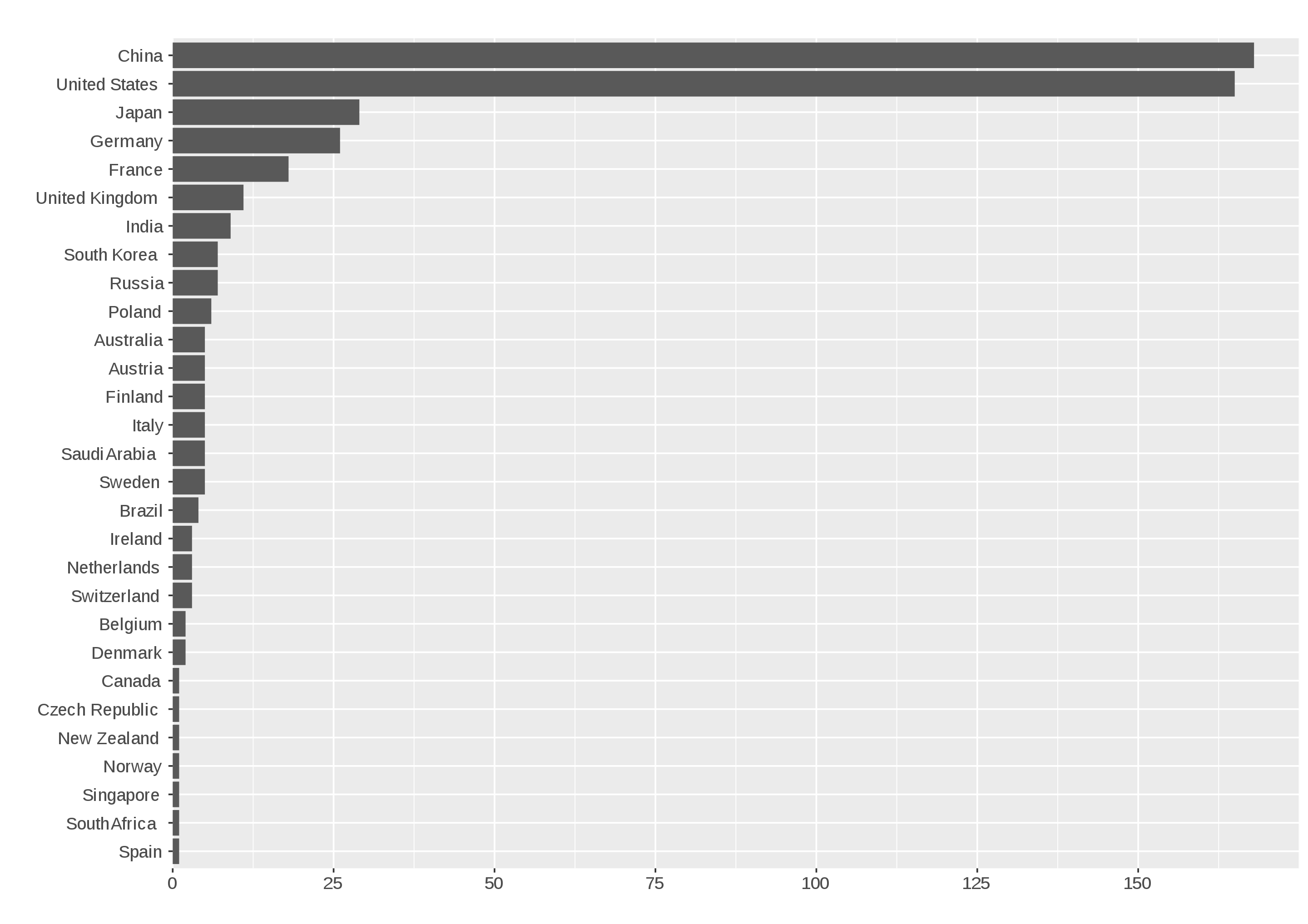

Fifteen years ago, China had no computers on the Top-500 list. Today it owns the top two spots. The #2 machine, which was the world’s fastest supercomputer from 2013 to 2016, uses Intel Xeon CPUs. But in 2015, the U.S. government banned the sale of these processors to China. The official reason for the ban was national security concerns, but many suspected a desire to recover the status as the world’s fastest computer for America may have been a strong motivation as well. China responded by very rapidly shifting to using its own Sunway CPUs, based on a new architecture and instruction set completed in 2016. The Sunway processors reportedly have 260 cores and the “Taihulight” supercomputer built from them runs at up to 125.44 petaflops (1 petaflop = one thousand million million floating point operations per second), a lead the US and Japan are unlikely to be able to catch up with anytime soon.

As computing power enables increasingly complex artificial intelligence (AI) systems that can control financial trading systems, power grids, and scientific research, the challenges of national technology competitions become apparent. But even the new web technology has its dark side. Social media has been implicated in helping cause the genocide in Myanmar against the minority Rohinga population. Russian meddling and manipulation of Facebook data by a company called Cambridge Analytica may have influenced the 2016 Brexit vote. Foreign hacking and social media manipulation were both alleged during the 2016 and 2020 US presidential election, although it’s unclear whether the intervention changed the outcome. In the course of investigating charges of Russian interference, details have come to light of just how compromised social media sites like Facebook have become and how much of their users’ data they hold. And in 2013 American whistleblower Edward Snowden released information to journalists showing that intelligence agencies such as the NSA and British GCHQ are systematically invading the privacy of citizens in a number of illegal ways. As a result of these disclosures, Snowden has been forced to live in exile in Russia. It is not clear, however, whether the practices have been discontinued.

Finally, even when there’s not an adversary regime like Russia spreading disinformation, Social Media algorithms create “filter bubbles” in which people only see information that doesn’t threaten their world-views. In an attempt to generate greater advertising revenues, social media platforms and search engines routinely direct users to information that will attract and hold their attention for the longest time possible. The objective of the algorithms is not necessarily to promote a certain worldview, but simply to keep the user engaged as long as possible so that more ads can be placed and sold. However, as a result, users are directed to information that conforms with their “profile” of beliefs and biases. When information that does not conform to the user’s preconceptions is presented, it is often presented in an adversarial way, to generate anger (which is another way to insure engagement). News and information are tailored either to conform to audiences’ beliefs and prejudices, or to outrage. As time goes on, people on different sides of issues can literally find themselves living in different worlds, basing their beliefs on different data, and believing the other side is irrational and evil.

Some have argued that global media access disproportionately benefits nations like the U.S. which has a multi-billion-dollar content-creation industry, and that it spreads values some societies disapprove of, including consumerism and pornography. Even in the U.S. and the developed world, the internet is changing from the democratic, peer-to-peer sharing institution it was designed to be, into a platform for commerce and media consumption. In the early days of the internet, communication was text-based because bandwidths were low. The advent of fiber optic network backbones in the 1990s and the worldwide web created the opportunity to communicate using images and ultimately streaming video. 4G and 5G cellular networks allow media to be streamed to smartphones and tablets. This rapidly expanding bandwidth created an opportunity for the internet to replace broadcast television just as it had replaced the analog, landline telephone network. But access may not be universally available for long.

As technology exploded, many people expected a renaissance of DIY content-creation, and the explosion of websites, blogs, vlogs, podcasts, Instas, snapchats and YouTube channels has definitely expanded the ability of regular people to be heard. Five billion YouTube videos are watched daily and 300 hours of video are uploaded every minute. On the other hand, more content is produced for the web by global corporations daily, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has begun to eliminate net neutrality so corporations can buy “fast-lane” access that will turn the web into just another platform for corporate media. The promise of the early internet was that even though corporations participated, it was basically a peer-to-peer platform. Eliminating net neutrality could potentially kill that, unless hackers can come up with a new disruptive technology that allows the people to stay ahead of the corporations. If corporations can pay to have certain types of data or media fast-tracked, they can also pay to have other types of information slow-tracked or even suppressed. Imagine if a group with deep pockets and a political agenda could start editing what you can see on the internet. Oh wait. Don’t imagine it. It’s already happening.

Media Attributions

- Panamax_container_ship

- 1599px-Pemex_gas_station

- Hugo_Chavez_in_Brazil-1861

- WTO.

- Screen Shot 2020-12-28 at 9.29.56 AM

- photograph-of-president-william-j-clinton-watching-vice-president-albert-gore-b3b7cc-small

- GEM_corn

- Maquiladora

- TPP_enlargement

- 1600px-WTO_protest_sign_(14988892087)

- Deng_Xiaoping_and_Jimmy_Carter_at_the_arrival_ceremony_for_the_Vice_Premier_of_China._-_NARA_-_183157-restored(cropped)

- 1280px-One-belt-one-road.svg

- Enlargement_of_the_European_Union_77

- 800px-Anti-Brexit,_People’s_Vote_march,_London,_October_19,_2019_05

- ARPANET_1970_Map

- HypertextEditingSystemConsoleBrownUniv1969

- First_Web_Server

- Internet_map_1024_-_transparent,_inverted

- Linus_Torvalds

- 2880px-TOP500_Supercomputers_by_Country_June_2016.svg

- 11534873615_d9ca4e86e1_z

- NN-save-the-internet