6.4 Types of Volcanoes

The products of volcanism that build volcanoes and leave lasting marks on the landscape include lava flows that vary in viscosity and gas content, and tephra ranging in size from less than a mm to blocks with masses of many tons. Individual volcanoes vary in the volcanic materials they produce, and this affects the size, shape, and structure of the volcano.

There are three types of volcanoes: cinder cones (also called spatter cones), composite volcanoes (also called stratovolcanoes), and shield volcanoes. Figure 6.29 illustrates the size and shape differences amongst these volcanoes and Table 4.1 provides a summary of their characteristics.

| Type | Tectonic Setting | Size and Shape | Magma and Eruption Characteristics | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinder cone | Various; some form on the flanks of larger volcanoes | Small (10s to 100s of metres) and steep (Greater than 20°) | Most are mafic and form from the gas-rich early stages of a shield- or rift-associated eruption | Eve Cone, northern B.C. |

| Composite volcano | Almost all are at subduction zones | Medium size (1000s of metres high and up to 20 km across) and moderate steepness (10° to 30°) | Magma composition varies from felsic to mafic, and from explosive to effusive | Mount St. Helens |

| Shield volcano | Most are at mantle plumes; some are on spreading ridges | Large (up to several 1,000 metres high and up to 200 kilometres across), not steep (typically 2° to 10°) | Magma is almost always mafic, and eruptions are typically effusive, although cinder cones are common on the flanks of shield volcanoes | Kilauea, Hawaii |

Shield volcanoes, which get their name from their broad rounded shape, are the largest. Figure 6.29 shows the largest of all shield volcanoes—in fact, the largest of all volcanoes on Earth—Mauna Loa, which makes up a substantial part of the Island of Hawai‘i and has a diameter of nearly 200 km. The summit of Mauna Loa is presently 4,169 m above sea level, but this represents only a small part of the volcano. It rises up from the ocean floor at a depth of approximately 5,000 m. Furthermore, the great mass of the volcano has caused it to sag downward into the mantle by an additional 8,000 m. In total, Mauna Loa is a 17,170 m thick accumulation of rock.

Kīlauea Volcano is also a shield volcano, albeit a much flatter one. Kīlauea Volcano rises only 18 m about the surrounding terrain, and is almost not visible in the scale of the diagram, however it still stretches over a distance of 125 km along the eastern side of the Island of Hawai‘i.

Composite volcanoes are the next largest. Mt. St. Helens is shown on the left of Figure 6.29. It rises 1,356 m above the surrounding terrain in the Cascade Range of the western United States, and has a diameter of approximately 6 km. Composite volcanoes tend to be no more than 10 km in diameter. Unlike shield volcanoes, composite volcanoes have a distinctly conical shape, with sides that steepen toward the summit.

Cinder cones are the smallest, and almost too small to see next to a volcano like Mauna Loa. Eve Cone is a cinder cone on the flanks of Mt. Edziza in northwestern British Columbia. It rises 172 m above the landscape, and has a diameter of under 500 m. Cinder cones have straight sides, unlike upward-steepening composite volcanoes, or rounded shield volcanoes.

6.4.1 Shield Volcanoes

Shield volcanoes, like the Sierra Negra volcano in the Galápagos Islands (Figure 6.30, top), get their gentle hill-like shape because they are built of successive flows of low-viscosity basaltic lava (Figure 6.30, bottom). The low viscosity of the lava means that it can flow for long distances, resulting in the greater size of shield volcanoes compared to composite volcanoes or cinder cones. The best-known shield volcanoes are those that make up the Hawaiian Islands, and of these, the only active ones are on the big island of Hawaii. Mauna Loa, the world’s largest volcano and the world’s largest mountain (by volume) last erupted in 1984. Kilauea, arguably the world’s most active volcano, has been erupting, virtually without interruption, since 1983. Loihi is an underwater volcano on the southeastern side of Hawaii. It is last known to have erupted in 1996, but may have erupted since then without being detected.

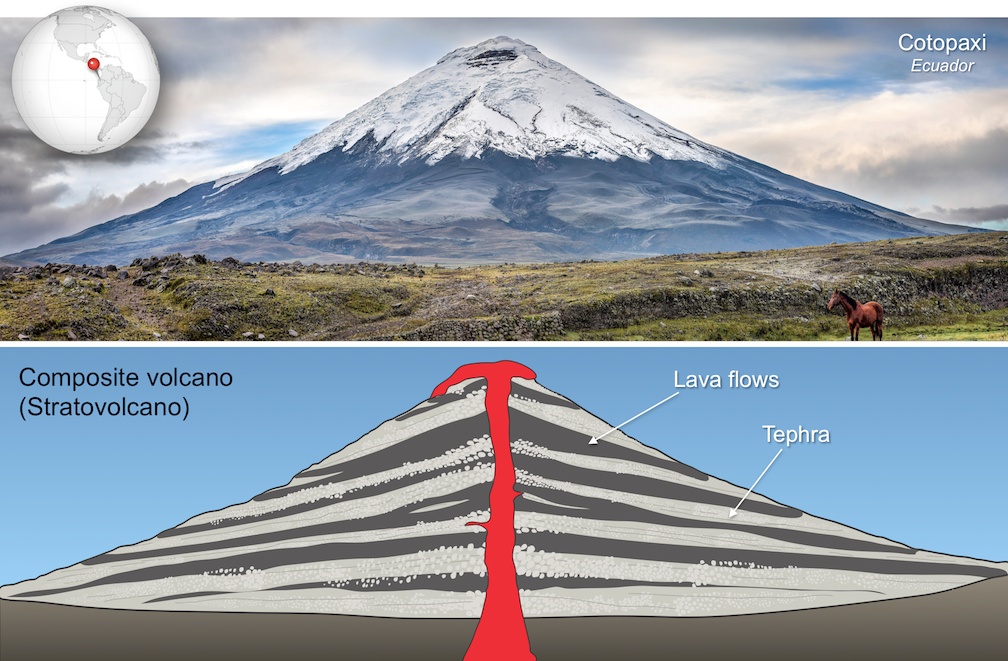

6.4.2 Composite Volcanoes (Stratovolcanoes)

Composite volcanoes, like Cotopaxi in Figure 6.31 (top), consist of layers of lava alternating with layers of tephra (blocks, bombs, lapilli, and ash; Figure 6.31, bottom). The layers (strata) is where the alternative name ‘stratovolcano’ comes from. Cotopaxi displays the characteristic shape of composite volcanoes, which have slopes that get steeper near the top of the volcano. The change in the slope reflects the accumulation of tephra fragments near the volcano’s vent. Composite volcanoes typically erupt higher viscosity andesitic (i.e., intermediate composition) and rhyolitic (i.e., felsic composition) lavas, which do not travel as far from the vent as basaltic lavas do. This results in volcanoes of smaller diameter than shield volcanoes. A notable exception is Mt. Fuji in Japan, which erupts basaltic lava.

From a geological perspective, composite volcanoes tend to form relatively quickly and do not last very long. If volcanic activity ceases, it might erode away within a few tens of thousands of years. This is largely because of the presence of pyroclastic eruptive material, which is not strong. Mount St. Helens, for example, is made up of rock that is all younger than 40,000 years; most of it is younger than 3,000 years. If its volcanic activity ceases, it might erode away within a few tens of thousands of years.

6.4.3 Cinder Cones (Spatter Cones)

Cinder cones, like Mt. Capulin in Figure 6.32, have straight sides and are typically less than 200 m high. Most are made up of fragments of scoria (vesicular rock from basaltic lava) that were expelled from the volcano as gas-rich magma erupted. Because cinder cones are made up almost exclusively of loose fragments, they have very little strength. They can be eroded away easily, and relatively quickly.

Text Attributions and References

This text of this chapter is adapted from:

- Section 11.3 of Physical Geology, First University of Saskatchewan Edition (2019) by Karla Panchuk. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

- Sections 4.2 of Physical Geology – 2nd Edition (2019) by Steven Earle. Licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

Other references used to compose text include:

- Rubin, K. (n.d.) Mauna Loa Volcano. Retrieved 23 August 2017. Visit website