3.3 Differentiation and Internal Structure

If you were to cut the planets in half, they would all exhibit internal layering like a cake. However, the relative thickness, state (solid vs liquid), and composition (rock vs ice) of these layers differs between planetary bodies, suggesting that formation conditions were not homogenous across the solar system. Let us look at this internal layering and its formation mechanisms in a bit more detail.

3.3.1 Differentiation

Remember that chondritic meteorites, with their abundant chondrules embedded in a silica-rich matrix, show us what the insides of primitive asteroids—those that have not been significantly altered since their formation—look like. Achondrites appear quite different from chondrites; they lack chondrules and oftentimes look like a chunk of igneous rock or metal. This difference is a result of heating; the parent bodies of achondrites grew large enough and built up enough heat to melt chondrules, matrix material, and other solid grains, allowing them to differentiate.

Differentiation refers to the separation of materials into layers based on their physical and chemical properties. All of the planets, as well as some dwarf planets, large asteroids, and large moons, experienced some form of differentiation early in their history. To undergo differentiation, these bodies had to accumulate enough heat to melt their solid rock, ice, or metallic components. This heat primarily came from collisions during accretion, gravitational compression, and radioactive decay (we will talk more about each of these sources in Chapter 5: Planetary Heating and Cooling). Once liquid, the heavier elements sank towards the center under the force of gravity while the lighter elements floated towards the surface, resulting in the formation of distinct layers with different compositions and densities. For the terrestrial planets and some other large rocky and icy bodies, planetary differentiation created a core, mantle, and crust; the core is the densest innermost layer while the crust is the least dense outermost layer. Later, when these bodies cooled, the distinct layers were preserved. Achondrite meteorites are actually pieces of the internal layers of other planetary bodies: iron achondrites broke off of a leftover planetary core, stony-iron achondrites (like pallasites) represent the core-mantle boundary, and stony achondrites represent from the mantle or crust. Considering we can’t drill into the mantle and core of the Earth, studying achondrites is an important approach scientists can use to better understand the evolution of planet interiors early in the solar system.

Watch the video below for another explanation of planetary differentiation.

3.3.2 Internal Structure and Composition of the Terrestrial Planets

The terrestrial planets are quite different from the giant planets. In addition to being much smaller, they are composed primarily of rocks and metals. These, in turn, are made of elements that are less common in the universe as a whole. On terrestrial planets, the most abundant minerals are silicates, which are composed of silicon and oxygen, and the most common metal is iron. When we look at the internal structure of each of the terrestrial planets (Figure 3.10), we see the evidence of differentiation: the densest metals are in a central core while the lighter silicates near the surface. Understandably, we know the most about the internal structure and composition of Earth—we do live on this planet after all! Let’s talk about the internal structure of the Earth in a bit more detail so we can use it as a point of comparison.

Overview of Earth’s Layers

As mentioned earlier, Earth consists of three main compositional layers: the crust, the mantle, and the core (Figure 3.11). The core accounts for almost half of Earth’s radius, but it amounts to only 16.1% of Earth’s volume. Most of Earth’s volume (82.5%) is its mantle, and only a small fraction (1.4%) is its crust. The Earth’s outermost layer, its crust, is rocky and rigid. There are two kinds of crust: continental crust and oceanic crust. Continental crust is thicker, and predominantly felsic in composition, meaning that it contains minerals that are richer in silica. The composition is important because it makes continental crust less dense than oceanic crust. Oceanic crust is thinner, and predominantly mafic in composition. Mafic rocks contain minerals with less silica, but more iron and magnesium. Mafic rocks (and therefore ocean crust) are denser than the felsic rocks of continental crust.

Earth’s mantle is almost entirely solid rock, but it is in constant motion, flowing very slowly. It is ultramafic in composition, meaning it has even more iron and magnesium than mafic rocks, and even less silica. Although the mantle has a similar chemical composition throughout, it has layers with different mineral compositions and different physical properties. It can have different mineral compositions and still be the same in chemical composition because the increasing pressure deeper in the mantle causes mineral structures to be reconfigured. Rocks higher in the mantle are typically composed of peridotite, a rock dominated by the minerals olivine and pyroxene.

The core is primarily composed of iron, with lesser amounts of nickel. Lighter elements such as sulfur, oxygen, or silicon may also be present. The core is split into two layers based on the material’s physical behavior: the outer core and the inner core. The temperature of the core, overall, is extremely hot, ranging from ~3500° to more than 6000°C (parts of the Earth’s core are hotter than the surface of the Sun, which is ~5500°C!). This high temperature makes the outer core liquid metal. However, the inner core remains solid, despite the high temperature, because the pressure at that depth is so high that it keeps the core from melting. Earth’s liquid outer core is responsible for its strong magnetic field!

Composition and Structure of Venus and Mars

Earth, Venus, and Mars all have roughly similar bulk compositions; about one-third of their mass consists of iron-nickel or iron-sulfur combinations, and two-thirds of the mass is from silicates. Because these planets are largely composed of oxygen compounds (such as the silicate minerals of their crusts), their chemistry is said to be oxidized.

Venus is in many ways Earth’s twin, with a mass 0.82 times the mass of Earth and an almost identical density (Earth’s density is 5.5 g/cm3 and Venus’ is 5.3 g/cm3). Due to a lack of seismic data from Venus, our knowledge of its internal structure and chemistry is in its infancy, but hopefully this will change with future missions. Considering its similar size and density to Earth, we think Venus has a comparable structure to Earth, consisting of an iron-nickel core (potentially with a liquid layer), a hot but still solid rocky mantle, and a solid and thin silicate crust.

Mars, by contrast, is rather small, with a mass only 0.11 times the mass of Earth. Despite the size difference, Mars has an internal structure that is proportionally similar to Earth’s! In other words, it looks like we took Earth and just shrunk it to be the same size as Mars. The jury is still out on whether or not Mars’ core is solid or liquid, however, recent analyses of seismic measurements from the InSight lander support the liquid metal martian core hypothesis (Nature, 2023. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06150-0)!

Read the Internal Structure sections of the Venus and Mars Wikipedia pages to learn more.

Composition and Structure of the Moon

The composition of the Moon is not the same as that of Earth. With an average density of only 3.3 g/cm3, the Moon must be made almost entirely of silicate rock. Compared to Earth, it is depleted in iron and other metals. It is as if the Moon were composed of the same silicates as Earth’s mantle and crust, with the metals and the volatiles selectively removed. These differences in composition between Earth and Moon provide important clues about the origin of the Moon, a topic we will cover in detail later in this chapter.

Although the Moon has a compositionally distinct core, mantle, and crust, the relative sizes of these layers are very different compared to the Earth. Studies of the Moon’s interior carried out with seismometers taken to the Moon as part of the Apollo program confirm the absence of a large metal core. Instead, the Moon has a proportionally very small iron-rich core consisting of a solid portion portion only ~240 km in radius surrounded by a liquid layer ~90 km thick. A hardened mantle likely containing pyroxene and olivine makes up the majority of the Moon’s interior, but between the mantle and liquid outer core lies a partially melted region. The lunar crust is more felsic in composition due to fractional crystallization. Its made mostly of plagioclase and has an average thickness of ~50 km.

We also know from the study of lunar samples that water and other volatiles have been depleted (or lost) from the lunar crust. The tiny amounts of water detected in these samples were originally attributed to small leaks in the container seal that admitted water vapor from Earth’s atmosphere. However, scientists have now concluded that some chemically bound water is present in the lunar rocks.

Read the Internal Structure of the Moon Wikipedia page and the Structure section of the Moon Wikipedia page to learn more.

Composition and Structure of Mercury

Mercury’s mass is one-eighteenth that of Earth, making it the smallest terrestrial planet. Mercury is the smallest planet (except for the dwarf planets), having a diameter of 4878 kilometers (radius of 2,440 km), less than half that of Earth. Mercury’s density is 5.4 g/cm3, much greater than the density of the Moon, indicating that the composition of those two objects differs substantially.

Mercury’s composition is one of the most interesting things about it and makes it unique among the planets. Mercury’s high density tells us that it must be composed largely of heavier materials such as metals. The most likely models for Mercury’s interior suggest that it has a proportionally large metallic iron-nickel core covered by a solid and comparatively thin silicate mantle and crust. Having a radius of ~2,070 kilometers, Mercury’s core makes up about 85% of the planet’s radius. We could think of Mercury as a metal ball the size of the Moon surrounded by a rocky mantle and crust only ~400 kilometers thick, collectively. Unlike the Moon, Mercury does have a weak magnetic field. The existence of this field is consistent with the presence of a large metal core, and it suggests that at least part of the core must be liquid in order to generate the observed magnetic field. Read the Internal Structure section of the Mercury (planet) Wikipedia page to learn more.

But what does Mercury’s internal structure tell us about its origin story? We have seen that, unlike the Moon, Mercury is composed mostly of metal. However, scientists think that Mercury should have formed with roughly the same ratio of metal to silicate as that found on Earth or Venus. How did it lose so much of its rocky material?

The most probable explanation for Mercury’s silicate loss may be similar to the explanation for the Moon’s lack of a metal core. Mercury is likely to have experienced several giant impacts very early in its youth, and one or more of these may have torn away a fraction of its mantle and crust, leaving a body dominated by its iron core. A recent alternative explanation suggests that, early on, heat from the young Sun evaporated much of the lighter, more volatile, silicates in the material that formed Mercury, leaving the planet with a majority of metals.

3.3.3 Internal Structure and Composition of the Giant Planets

Chemically, each giant planet is dominated by hydrogen and its many compounds. Nearly all the oxygen present is combined chemically with hydrogen to form water (H2O). Chemists call such a hydrogen-dominated composition reduced. Throughout the outer Solar System, we find abundant water (mostly in the form of solid water ice) and reducing chemistry.

The two largest planets, Jupiter and Saturn, have nearly the same chemical makeup as the Sun; they are composed primarily of the elements hydrogen and helium, with 75% of their mass being hydrogen and 25% helium. On Earth, both hydrogen and helium are gases, so Jupiter and Saturn are sometimes called gas planets. But this name is misleading. Jupiter and Saturn are so large that the gas is compressed in their interior until the hydrogen becomes a liquid. Because the bulk of both planets consists of compressed, liquefied hydrogen, we should really call them liquid planets.

Under the force of gravity, the heavier elements sink toward the inner parts of a liquid or gaseous planet. Both Jupiter and Saturn, therefore, have cores composed of heavier rock, metal, and ice, but we cannot see these regions directly. We must infer the existence of the denser core inside these planets from studies of each planet’s gravity.

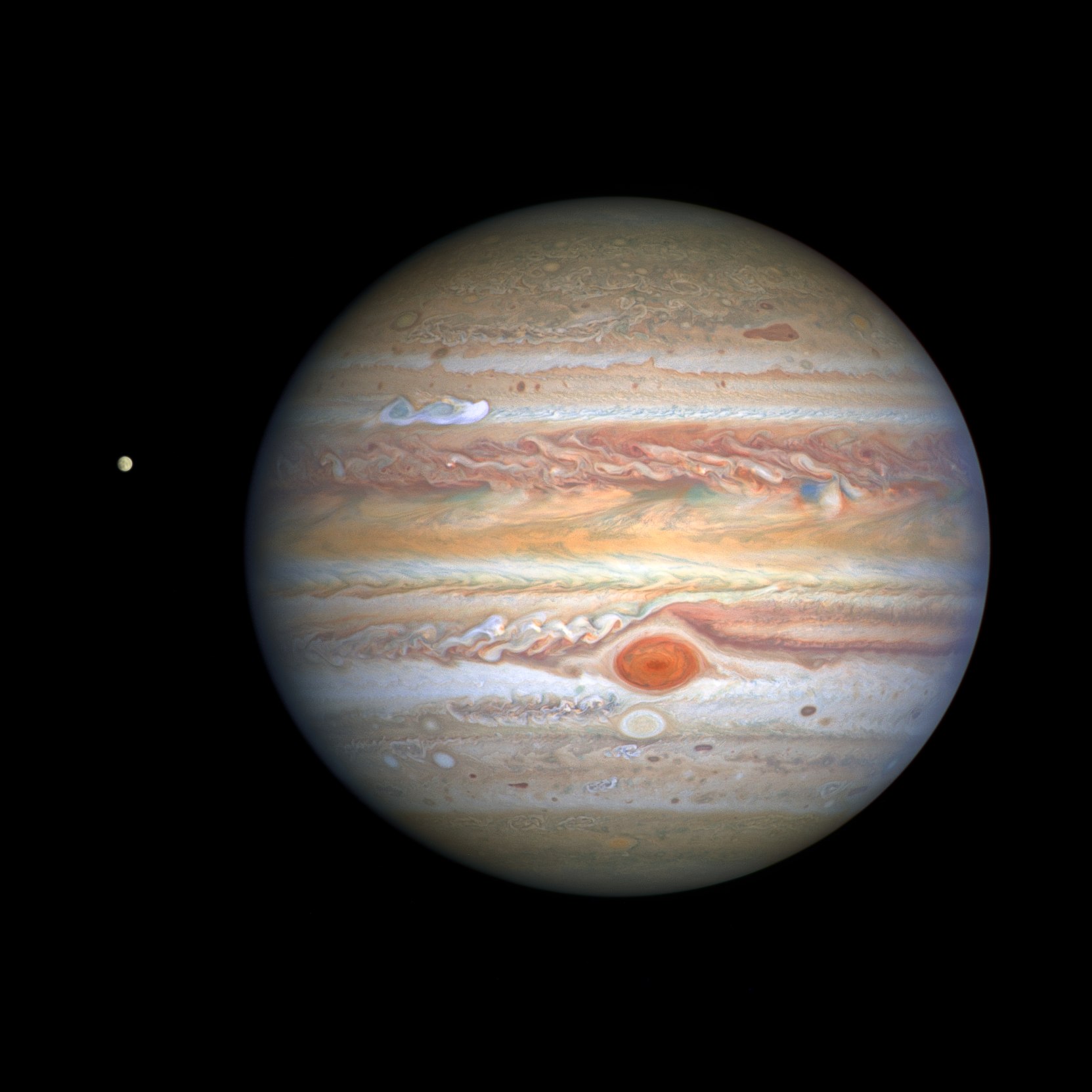

When we look down at each giant planet from above, all we see is a thick atmosphere with swirling clouds. The rapid rotations of Jupiter and Saturn create extreme weather patterns in their atmospheres. Jupiter’s atmosphere, for example, features a counterclockwise rotating cyclonic storm in its southern hemisphere known as the Great Red Spot, which has been visible to humans for over 300 years.

Beneath the gaseous, primarily hydrogen atmospheres of Jupiter and Saturn lies a region where pressure is so great that the hydrogen turns into a liquid. Below this liquid hydrogen layer, where pressure is even higher, liquid hydrogen exists in its metallic state. Well-defined boundaries do not exist between any of these layers; instead, they gradually fade into each other. This means neither Jupiter nor Saturn have a solid surface that an astronaut or robot could stand on like the terrestrial planets! (We will discuss these layers even more in a later chapter.)

Uranus and Neptune are much smaller than Jupiter and Saturn, but each also has a core of rock, metal, and ice. Uranus and Neptune were less efficient at attracting hydrogen and helium gas, so they have much smaller gaseous atmospheres in proportion to their cores. While Uranus and Neptune did not attract significant hydrogen and helium gas, they did eventually collect a lot of ices to develop large icy mantles, which is why they are referred to as ice giants. However, don’t let the word icy fool you. The mantles of Uranus and Neptune are strange; they are a very hot and dense fluid made of a mixture of methane, ammonia, and water. (Remember, planetary scientists use the word “ice” to refer to a volatile compound in any state—solid, liquid, or gas. It’s confusing, I know!) This fluid mixture is neither considered a solid nor a liquid in the conventional sense. Rather, it is considered a supercritical fluid. You might see the mantles of Uranus and Neptune referred to as hot ice oceans, but keep in mind, that they are not a true liquid!

3.3.4 Internal Structure and Composition of Moons, Asteroids, and Comets

Chemically and structurally, Earth’s Moon is like the terrestrial planets, but most moons are in the outer Solar System and have compositions similar to the cores of the giant planets around which they orbit. The four largest moons of Jupiter, known as the Galilean moons, are Ganymede, Callisto, Io, and Europa. They are named after the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, who first observed them through a telescope in 1610. The interiors of Ganymede, Io, and Europa have a layered structure. Interestingly, Callisto’s interior is not distinctly layered which suggests it experienced only partial differentiation. We will talk more about each of the Galilean moons in a later chapter.

Most of the asteroids and comets, as well as the smallest moons, were probably never heated to the melting point. However, some of the largest asteroids, such as Vesta, appear to be differentiated; others are fragments from differentiated bodies. Many of the smaller objects seem to be fragments or rubble piles that are the result of collisions.

Text Attributions

This text of this chapter is adapted from:

- Sections 7.2, 9.1, 9.5, and 10.1 of OpenStax’s Astronomy 2e (2022) by Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney Wolff. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access full book for free at this link.

- Section 22.4 by Karla Panchuk in Physical Geology – 2nd Edition (2019) by Steven Earle. Licensed under CC BY 4.0, except where otherwise noted.

- Chapter 17 of Introduction to Earth Science, Second Edition (2025) by Laura Neser. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Media Attributions

- “What is Planetary Differentiation?” YouTube, uploaded by AstroPhil, 24 Nov 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfmLI150g4w.

an adjective used to describe rocks or magmas that are rich in silicon, oxygen, and other light elements that form minerals like quartz and feldspar

an adjective used to describe rocks or magmas that are relatively poor in silica and oxygen and rich in iron and magnesium

an adjective used to describe igneous rocks or magmas that are rich in iron and magnesium and very poor in silicon and oxygen

A substance at a temperature and pressure above its critical point, where distinct liquid and gas phases do not exist, but below the pressure required to compress it into a solid. Supercritical fluids generally have properties between those of a gas and a liquid. (from Wikipedia)