Summary of Chapter:

In this chapter we review key terms and concepts in raising critical consciousness and develop our critical thinking skills. We share the history and focus of liberation psychology, explore decolonizing psychology approaches, discuss cultural humility, and define and provide questions for consciousness raising and critical thinking.

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the contributions of current scholar-activist psychologists and their contribution to the field and social justice movements.

- Demonstrate knowledge about liberation psychology, how it applies to your life, and how it applies to introductory psychology theories and concepts.

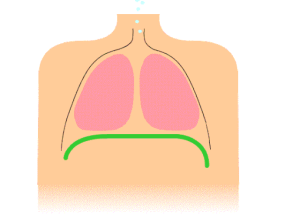

This workbook might bring up a variety of thoughts and feelings. You may have well used and helpful strategies to help you manage whatever comes up for you. We offer an embodiment practice for grounding, being present with the material, and potentially for managing any thoughts or feelings that come up for you.

Embodiment Practice Breath Exercise[1]

- Sit or lie down in a comfortable place.

- Bring your awareness to your breaths without trying to change how you’re breathing. Allow your breathing to occur while gently bringing awareness to each breath.

- Alternate between normal and deep breaths a few times. Are there any differences between normal breathing and deep breathing? Notice how your abdomen expands with deep inhalations.

- How does shallow breathing feel compared to deep breathing?

- Practice deep breathing for a few minutes.

- Place one hand below your belly button, keeping your belly relaxed, and notice how it rises with each inhale and falls with each exhale.

- Allow yourself to let out a loud sigh with each exhale.

- Begin the practice of “breath focus” and continue deep breathing. Allow an image, or a focus word or phrase that will support relaxation.

- You might imagine that the air you inhale brings waves of peace and calm throughout your body. Mentally say, “Inhaling peace and calm.”

- Imagine that the air you exhale washes away tension and anxiety. You can say to yourself, “Exhaling tension and anxiety.”

History/Context:

What is liberation psychology, what is its history, and why does it matter?

Liberation psychology is an approach to psychology. This approach focuses on understanding and addressing the effects of oppression, emphasizing social justice, collective healing, and empowerment of marginalized communities. It seeks to decolonize psychology by shifting from an individual-focused, Western perspective to one that considers historical and systemic injustices. This is an approach that is not included in most traditional psychology textbooks.

Dr. Anneliese Singh, 2019-2020 President of the Society of Counseling Psychology, stated:

We all have a personal experience of liberation. It is the feeling deep in our bones when we are free from all the internalized messages we were taught of who we were supposed to be and the expansion we feel when we transform these messages into critical consciousness to act upon the world and change it. The project of working toward liberation for all people who experience oppression is one that frees all of us along the way. Liberation is a psychological construct, but it only has meaning when we enact it…Think about it. What would a world free of racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, ableism, anti-immigrant sentiment, and other oppressions ‘look like?’.[2]

(1.1) Take a moment to engage in visioning. What would a world free of racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, ableism, anti-immigrant sentiment, and other oppressions ‘look like?’

Liberation psychology is an approach that focuses on understanding individuals, communities, and society from the perspective of those who experience oppression and marginalization[3][4][5]. This framework has its origins in the work of influential scholars and activists like Paulo Freire, Ignacio Martin-Baro, Franz Fanon, W.E.B. Dubois, Amilcar Cabral, and Lillian Comas-Díaz.[6]

As a global movement, Liberation psychology has been shaped by various theories and approaches, including:

- Indigenous perspectives

- African philosophies

- Mujerista (Latina feminist) thought

- Decolonizing and post-colonial theories

- Feminist ideologies

- Critical race theory

- Transnational studies

- Intersectional frameworks

This diverse foundation allows Liberation psychology to offer a comprehensive understanding of how different forms of oppression intersect and impact individuals and communities.

Some notable contributors to the field of liberation psychology

A French West Indian psychiatrist, and political philosopher from Martinique

Fanon studied the psychological impacts of colonialism, focusing on what he termed the “psychopathology of colonialism.” This concept highlights the harmful mental and emotional effects that colonial systems had on both the colonized people and the colonizers. Additionally, he explored the emotional trauma experienced by Black people due to racist treatment, shedding light on the profound psychological damage inflicted by these oppressive systems. By examining these effects, Fanon helped deepen our understanding of how colonialism and racism can seriously harm a person’s mental health and emotional well-being. He is well known for his books “Black Skin, White Masks” (1952) and “The Wretched of the Earth” (1961).

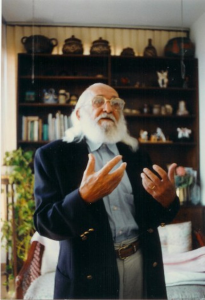

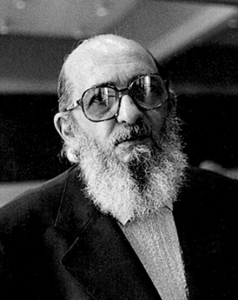

Paulo Freire (1921-1997)

A Brazilian educator and philosopher who challenged the elitism of education and supported critical analysis of education, ie, critical pedagogy. Pedagogy is the art and science of teaching. In his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), he argues that education and educational theories need to center the experiences and needs of the marginalized in capitalist societies. He argued that education should support critical consciousness development and the liberation efforts of those who are marginalized.

Dr. Ignacio Martin-Baro (1942-1989)

A scholar, social psychologist, philosopher, and Jesuit priest who promoted the argument that psychology should “address the historical context, the social conditions and aspirations of the people”. He believed that in places where people are oppressed, the solution to mental health problems is to transform society towards liberation. He did not believe that the field of psychology was impartial or objective, nor did he believe in universal psychological theories. Instead, he developed a psychological perspective that was critically committed to questioning power and oppression. Martín-Baró argued that psychologists must consider multiple contexts, especially structural oppression and violence, when understanding people’s mental health. He believed that if psychologists fail to do this, they inadvertently become complicit in the social injustices that likely caused the mental health problems in the first place. He vocally questioned theories found in mainstream psychology and authored the book “Writings for a Liberation Psychology” (1996). Tragically, he was murdered by the Salvadoran Army in 1989 at the University of Central America in San Salvador.

Dr. Lillian Comas-Díaz

Dr. Lillian Comas-Díaz

A clinical psychologist, scholar, and educator whose work focuses on culturally responsive approaches to healing racism based trauma that identify the root causes of trauma as sociopolitical and historical. She advocates therapy as a space to engage in critical thinking about systemic impacts on one’s mental health and decolonize one’s thinking via deconstructing messages learned from systems of oppression. She has contributed significantly to the field of liberation psychology, co-authoring the book “Liberation Psychology: Theory, Method, Practice, and Social Justice” (2020) which challenges traditional Western‑based psychology. The book contextualizes the development and methods of liberation psychology and makes clear its relationship to social justice, activism, and fighting oppression.

Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis

Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis

A licensed psychologist, ordained minister, sacred artist, and is the 2023 president of the American Psychological Association. Her clinical and research work focus on experiences of both interpersonal trauma and the societal trauma of oppression. She is one of the founding psychologists who worked in the field of racism based trauma. She co-wrote a chapter in the book “Liberation Psychology: Theory, Method, Practice, and Social Justice” (2020).

(1.2) Have you heard of any of the above contributors to the field of liberation psychology? If so, what did you learn about them? If not, pick one and engage in a brief exploration of their views and work.

Before engaging in further exploration of liberation psychology, it is important to focus on the term oppression. Discussions of oppression will be found in every chapter of this workbook as it is central to understanding the need for liberation. Why do we need to liberate ourselves at all? An answer is because of oppressive dynamics.

What is oppression?

What is oppression?

There are many definitions of oppression.

The Icarus Project is an organization that functions as an educational and support project for and by people who have experienced and are diagnosed with mental illness. They define oppression as “the systemic and institutional abuse of power by one group at the expense of others and the use of force to maintain this dynamic. An oppressive system is built around the ideology of superiority of some groups and the inferiority of others. This ideology makes those designated as inferior feel confined, ‘less than,’ and hinders the realization of their full spiritual, emotional, physical, and psychological well-being and potential.

Some people with mental illness are often portrayed as ‘others’ and are marginalized via social, mental, emotional, and physical violence which prevents their full inclusion in the community. Oppression enables those in charge to have access to control resources and choices, while making those labeled as inferior vulnerable to poverty, violence, and early death.

It is a set of processes, actions, and ideas that hinder the oppressed from exercising their full freedom of choice and having access to resources. These systems of inequality operate at internalized, institutional, and interpersonal levels to distribute advantages to some and disadvantages to others.”

David & Derthick (2018), who wrote the book, The Psychology of Oppression, offer the following. “Oppression occurs when one group has more access to power and privilege than another group, and when that power and privilege is used to maintain the status quo (i.e., domination of one group over another). Thus, oppression is both a state and a process, with the state of oppression being unequal group access to power and privilege, and the process of oppression being the ways in which inequality between groups is maintained” (p. 4).[7]

Institutional oppression refers to the policies, procedures, common practices, and laws that perpetuate a cycle of social inequity. This disadvantages groups oppressed by society and privileges groups that are dominant or hold the most power in a given society. Institutional oppression is promoted overtly or covertly by all institutions, for example, schools, government, housing, criminal justice, health, mental health, and media. The range of institutional oppression includes overt rules that state that Black people are not allowed to wear their natural hair at work or in school, to laws that provide stiffer sentences for being caught with crack cocaine as opposed to heroin. They also include covert practices, such as findings that defendants with darker skin are sentenced to higher numbers of years in jail for the same crime as their lighter skinned counterparts.

Interpersonal oppression refers to conscious or unconscious discrimination by groups in power toward marginalized individuals or groups. This occurs when groups with privilege discriminate against, isolate, minimize the experience of, and or dismiss groups without historical structural power. This can be done through microaggressions, jokes, derogatory comments, and physical violence. This is often the type of oppression that people think of first, bigoted people who engage in discrimination. Interpersonal oppression is an important and impactful area, but it is important to remember that it is not the only arena where oppression functions, and if we create more equitable institutions we can actually prevent some degree of harm on the interpersonal level.

Internalized oppression refers to how people—whether they realize it or not—absorb society’s messages about social ranking. Messages about who is more intelligent or less, more prone to criminality or less so, more attractive or less, and who we should aspire to be as opposed to who we should fear becoming. In this ranking, people with identities of privilege are placed above those with marginalized identities. As Denneny (1981) put it, “Society does not hate us because we hate ourselves; we hate ourselves because we grew up and live in a society that hates us.”[8]

When people constantly hear messages about who is “better” or “worse” in society, they can start to believe them. Marginalized/Oppressed individuals and communities may begin to see themselves as less valuable and act/make decisions from that belief, while privileged groups may see themselves as superior and act/make decisions from that belief. Over time, these beliefs help reinforce unfair systems that keep some groups in power and others at a disadvantage.

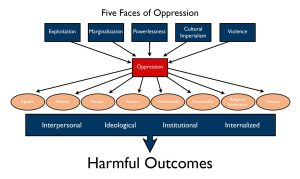

David & Derthick’s (2018) figure in The Psychology of Oppression illustrates oppression across institutional, interpersonal, and internalized levels, highlighting both overt (e.g., discriminatory laws) and covert (e.g., internalized bias) forms. It emphasizes how oppression operates systemically, socially, and psychologically, underscoring the need for multidimensional interventions.

Oppression plays a major role in many of the “-isms” that harm people’s lives. When we talk about oppression, we’re not just talking about diversity or differences between people—we’re focusing on how power affects certain groups. Discussions about diversity usually highlight the fact that we all have different social identities. Social identities shape how people see themselves, who they can become, and the groups they belong to.[9] Being part of a social group can provide a sense of belonging, purpose, and self-worth. However, how society views that group—positively or negatively—can also shape a person’s experience.

Instead of only thinking about diversity and difference, it’s important to consider how oppression and power impact people’s lives. For example, people don’t face worse health or educational outcomes simply because of their race, gender, sexuality, immigration status, ability, class, or ethnicity. These risks exist because of systems that uphold racism, sexism, cissexism, heterosexism, xenophobia, ableism, classism, and ethnocentrism. So it’s not just about race, it’s about racism. It’s not the identity that is the focus, it is the ism that produces differing access or barriers to resources, safety, representation, and power, and it is not just about who is oppressed, it is about who is oppressing or benefits from the oppression.

The Relationship between Identity and Oppression

| Social Identity | Form of Oppression |

| Gender | Sexism and Cissexism |

| Race | Racism |

| Ethnicity | Ethnocentrism |

| Sexuality or Sexual Orientation | Heterosexism and Homophobia |

| Socio-economic Class | Classism |

| Age | Ageism and Adultism |

| Religion | Islamophobia, Anti-Semitism, Fundamentalism, and others |

| Disability | Ableism |

| Body Size | Sizeism |

Oppression is not just an academic theory. It is important to identify how it operates at institutional and structural levels in ways that deny or limit some people’s access to resources such as education, jobs, physical, emotional and sexual safety, housing, loans, food, and more, and impacts people at their very core. It has real life consequences and negatively impacts individuals, families, communities, and societies while simultaneously privileging individuals, families, communities, and societies. In Madness and Oppression: Paths to personal transformation and collective liberation (2015), The Icarus Project asked their members to describe, in their own words, what oppression feels like, how it impacts emotions, behaviors, how people see themselves, their ability to work, and social relationships.

The accordion menu below organizes oppression-related issues into expandable sections. Follow these steps to navigate it: Click a Section Title to expand its content. Clicking again will collapse it.

Social identities were mentioned above. They are the different groups we belong to that shape how we see ourselves and how we’re perceived by others. These identities are based on things like race, gender, class, religion, ability, and more. Some of these identities give people more power or advantages in society, while others can lead to unfair treatment or barriers. For example, think about how someone’s gender might affect the way they are treated in school, at work, or in the media. All of this is shaped by our history and cultural systems of power.

In liberation psychology, we look at how social identities connect to oppression and privilege. We ask: Who has power? Who is left out? How can we change systems to create justice and equality? Understanding social identities helps us see and understand these patterns, as well as how we could work toward liberation.

(1.3) What are your social identities?

(1.4) What is psychology’s story about your social identities, your cultures, your communities? What, if anything, does psychology say about the injustices you face? Your privileges, strengths, and who benefits from these narratives? What does psychology say about the oppressions and injustices you experience and the method by which one can end them?

Liberation psychology is an approach that resists oppression, engages in social action, and calls on the field of psychology to center justice. Liberation psychologists do not say that you have to throw out everything from traditional psychology, however, there is a call to create new theories, research and findings, as well as reconceptualize theories, research, and findings in ways that center the experiences of those who live with the impacts of oppression.

Liberation psychology is an approach that resists oppression, engages in social action, and calls on the field of psychology to center justice. Liberation psychologists do not say that you have to throw out everything from traditional psychology, however, there is a call to create new theories, research and findings, as well as reconceptualize theories, research, and findings in ways that center the experiences of those who live with the impacts of oppression.

How does this approach work?

Liberation psychologists have argued that there is a need to explore root causes of distress in theory and practice.

For example, instead of only focusing on individual reasons that people engage in violence, people should also explore how systems of oppression, ie, racism, sexism, and classism are inherently violent and how that violence influences individual, group, and community practices and development. Instead of saying “those people are criminals,” liberation psychologists would have us look at their context; what resources were people given or denied, what opportunities are in the neighborhood, has the community experienced disasters or oppression, do people feel hopeless and helpless about the future, does society hold stereotypes and discriminate against people? The goal is not to excuse behavior but to do our best to understand its complexity so interventions and changemaking can occur that make sense and work for the people in that neighborhood.

Liberation psychologists work within the system of psychology and also engage in critical examination of the field. One way to critically examine the field is to look at the history of psychology and an example of a prominent figure.

- Traditional textbooks rarely center on the fact that one of the early presidents of the American Psychological Association, Lewis Terman (1923), was a prominent supporter of eugenics. This doctrine supports reproduction as a method to improve the human gene pool with “desirable” traits while attempting to prevent the reproduction of those with “undesirable” traits, often associated with the poor and working class, people with disabilities, and People of Color.

For eugenicists, these desirable traits are associated with Whiteness and White people. Terman was a member of many eugenicist organizations, including the Human Betterment Foundation, the American Eugenics Society, and the Eugenics Research Association, where his research at Stanford focused on promoting eugenics.

- Terman is generally recognized in textbooks as the developer of the Stanford-Binet IQ test, however it has been argued that “Terman used his test to present an argument of IQ deficiency in Indigenous, Mexican, and Black communities, supporting theories of racial intelligence that other eugenicists … embraced”[10] He created the scale to support segregation in education. Terman himself stated “dullness… seems to be racial, or at least inherent in the family” and found with “extraordinary frequency among Indians, Mexicans, and negroes”. Despite criticisms, this test continues to be used to this day.

- The fact that Terman was elected president of the American Psychological Association, at the very least, indicates that many psychologists of the time were neutral, if not supportive of his views. Have you heard about this aspect of Terman when learning about him in Introductory to Psychology or History of Psychology courses?

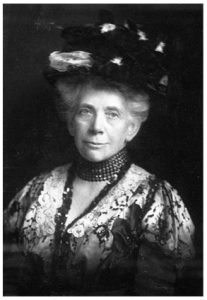

It is important to note that early women in the field of psychology faced significant discrimination based on sexist notions of their abilities to accomplish academic work. Mary Calkins, Christine Ladd-Franklin, and Mary Floyd Wasburn experienced discrimination in the field.

- Christine Ladd-Franklin and Mary Calkins both completed all of the requirements for their doctorates. However, both were denied their doctorates; Ladd-Franklin from Johns Hopkins and Calkins from Harvard[11].

- 44 years after completing her requirements, Christine Ladd-Franklin was granted her doctorate in 1926 during the Johns Hopkins’ celebration of their 50th anniversary.

- Years after she completed her requirements at Harvard, Mary Calkins was offered her doctorate from Radcliffe College (a liberal women’s arts college that functioned as the female counterpart to the all-male Harvard) in 1902. She declined the offer, which came about as an agreement created for women who had studied at Harvard but did not receive degrees from the institution.[12]

And at the same time as we acknowledge the very real discrimination women experienced when pursuing their degrees, it is also important to note that “Women psychologists in 1906 can be described generally as Anglo-Saxon Protestants of privileged middle-class backgrounds. They were similar to men psychologists… Most were born in the Northeastern or Middle-Western United States, though some were Canadians and a few of the men were European born; several were born abroad as children of missionaries…The median age of the women in 1906 was 39.5, and the median age for men was 39. The median age at completion of the undergraduate degree for the women was 22,5, for the men 22.” [13]

- Even in their experiences of oppression, these women also experienced enough privilege to allow them to access academia.

- Acknowledging these dynamics allows us to see early influences on the development of the field of psychology in the United States and hopefully encourages us to critically think about the context in which early theories and practices developed.

Let’s look again at Liberation Psychology and its perspective on oppression.

Liberation Psychology utilizes a strength-based approach to understanding oppressed communities, and offers alternatives that contextualize human experiences within their social, cultural, political, spiritual, and economic realities. Strengths-based approaches began as a “strengths perspective” framework that emphasizes the strengths and competencies of youth and families.[14] This perspective has been utilized in multiple disciplines, including psychology.

- Liberation psychologists encourage an emphasis on cultures and communities’ strengths and competencies.

- This framework is non-pathologizing, it does not view people, cultures, or communities solely through a lens of their problems and deficits. With a focus on strengths, there is more room for joy, positive self and other regard, and motivation for change.

- This perspective highlights that people and communities are not only oppressed; they have abilities and histories that have helped them survive and sometimes thrive, and this should be honored. For example, when working with LGBTQ+ communities, Liberation Psychology writers Singh, Parker, Aqil, & Thacker (2020) highlight stories of individual and collective resilience and resistance.[15]

- Instead of only asking LGBTQ+ people about their oppression and pain, they center the reality that many LGBTQ+ people seek and find affirming communities, engage in liberation movements to resist transphobic and heteronormative currently and in the past, and how LGBTQ+ movement engagement has influenced multiple other social justice movements.

(1.5) How is liberation psychology different from other theories of psychology that you have been exposed to? What parts of it speak to you or don’t make sense to you?

Understanding Colonialism: Past and Present

Liberation psychologists point to the ways that the field of psychology has been colonized.

Colonialism and colonization are complex topics that people teach courses on and write books on. Before we describe how liberation psychologists discuss the field being colonized, we will provide a brief framework for understanding what colonization is, what it has meant historically, and how it applies today, as described by Dr. Jennifer Mullan in Decolonizing Therapy (2023).[16]

Colonialism is the process by which powerful nations take control over other lands and peoples, often through violence, exploitation, and cultural erasure. Historically, colonialism was justified by beliefs that certain cultures and ways of life, such as those tied to Western religion, economic systems, and governance, were superior. This led to the forced removal, enslavement, and oppression of Indigenous peoples across the world, as colonizers sought land, wealth, and resources for their own gain. In the Americas, this took form through policies like the Indian Removal Act and chattel slavery, which stripped Indigenous and African-descended peoples of their land, rights, and autonomy.

Colonialism is not just a thing of the past. The economic, political, and psychological impacts of colonialism can be seen in persistent inequalities and land dispossession. Liberation psychologists recognize that colonialism has influenced the field of psychology itself, shaping how mental health, identity, and emotional responses to oppression are understood and treated. Liberation psychology aims to decolonize the way we understand and support each other.

How is colonialism experienced today?

According to Merriam-Webster, colonialism is the “subjugation of a people or area especially as an extension of state power.” Nations put a significant amount of money into “exploring and discovering” lands for their nations to take over, control, and exploit the resources of other countries and lands to benefit their own. Though we know colonialists did not discover any lands, the places they subjugated through physical aggression and psychological warfare existed and thrived before colonists arrived.

- Colonialism is not only what happens within a country’s borders. Currently, “there are 61 colonies or territories in the world. Eight countries maintain them: Australia (6), Denmark (2), Netherlands (2), France (16), New Zealand (3), Norway (3), the United Kingdom (15), and the United States (14).” [17]

- Even when there is no longer an official colony or practice of colonization, people who have been colonized often internalize the messages of colonization (ie, they and their cultures are inferior, that they are not to be trusted to create their own institutions, and that their spiritual belief systems are false and harmful) and pass these internalized messages down through generations.

- At its heart, colonialism is an ongoing process of violence acted upon Indigenous people across the globe to stamp out Indigenous people and their cultures for national wealth and personal gain. Colonialism is planned and intentional. It is where “some people exploit other lands and peoples of such lands because of a belief that it is their destiny or right to do so, which is based on their perceived superiority over other people…colonial theory is about passing on or propagating what one believes are superior, better, or more civilized ways of believing and doing things (e.g., Christianity, capitalism, Western culture and norms)”.[18]

- Colonial goals of attaining wealth for the nation state and personal gains for individual colonizers are supported through beliefs and propaganda about the inferiority of Indigenous people and their cultures and the superiority of colonizers and their culture. Colonialism in America became instituted through acts such as the Indian Removal Act and chattel slavery. Indigenous People in the Americas still do not have control over their land.

- Colonization causes trauma. It is violent; it comes with acts of physical aggression against communities and individuals, emotional and spiritual coercion and manipulation, and creates false narratives that live within current families, communities, and institutions.

- Colonialism pathologizes the emotions of those who have been harmed and victimized. It sends messages that tell people they should not be angry, frustrated, and enraged when they experience and name the trauma inflicted upon them. It does not view the emotional reactions of those who have experienced colonization as healthy responses to abusive behaviors.

Dr. Rupa Marya creates an image of what contributes to and upholds colonization, which she presented at Bioneers on Late Stage Capitalism. Dr. Marya & Raj Patel’s work, in the book Inflamed: Deep medicine and the anatomy of injustice (2021), “illuminates the hidden relationships between our biological systems and the profound injustices of our political and economic systems…It’s connected to the number of traumatic events we experienced as children and to the traumas endured by our ancestors.” They explore colonization as one of the traumas we have endured that impacts us down to our biology. These factors are currently still at play.

We feel it is important to say, in the end, colonialism is an ongoing process, and so is the fight for liberation. The fight for liberation is a fight for decolonization, community sovereignty and power, land sovereignty, and emotional freedom.

- Inspired by Dr. Marya’s work, Michelle Holliday offers an alternate image that points to an alternative framework to a colonized view. The author calls it a “Life-Honoring Worldview.”

- This framework points to different ways we can be connected to ourselves, one another, institutions, and the land. It also offers thoughts on how we can practice liberation.

Liberation psychologists acknowledge that much of Western psychology prioritizes the theories and research of White, cisgender, middle to upper class, sane, monotheistic, able-bodied, men and promotes the theories and research as if they were universal truths that apply to all people.

- “Coloniality of knowledge” and “coloniality of being” in psychology:[19][20]

- The coloniality of knowledge refers to the way that dominant Western psychology prioritizes individualism and focuses on personal growth and self-actualization as the goals and universal standards that all people should be held to.

- The individual focus calls for people to ignore the ways that Western psychology has contributed to the violence and dispossession of groups of people.

- Coloniality of being emphasizes the influence of racialized violence and colonialism.

- It highlights how the individualistic focus on gaining material wealth contributes to colonizing other countries and people and ecological degradation.

- Liberation psychologists argue that there is a need to rethink Eurocentric ways of thinking and being as optimal and true for all people.[21]

What does it mean to decolonize psychology?

Many have identified how therapy practices and focuses on the individual have harmed people who have sought help. That people have been made to feel as if their suffering was their fault, while their communal histories and experiences with violence, migration, war, and more were minimized or ignored in favor of individual coping strategies and medication.

- It is not to say that this focus does not work for some people, but that it does not work for all people, though it is portrayed that way.

- Decolonizing psychology leads to a focus on collective healing and wellness in the context of addressing the wounds of colonialism and oppression. In therapy, that can mean directly addressing cultural dynamics and experiences of oppression. It means understanding that oppression plays a significant part in people’s mental health.

- In psychology courses, it can mean the same. Classes can identify ways that theories and ideas are connected to colonialism and oppression. Classes can address the ways that theories have been used to benefit groups of people or marginalized groups through theory, research, or practice. Information can be provided that challenges the universality of said theories and encourages people to ask questions.

Who has been doing this work?

It is important to highlight that Indigenous people in America have been doing the work of decolonizing therapy.

- People like Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart and Eduardo and Bonnie Duran. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart is an Associate Professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and director of Native American and disparities research in the University of New Mexico’s Division of Community Behavioral Health.

- Her research focuses on “historical trauma,” which speaks to the trauma that Indigenous people experienced in the United States (colonization, attempted genocide, separation of children from families, forced assimilation in boarding schools, environmental oppression, displacement, and more).

- She describes historical trauma as “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding across generations including one’s own lifespan” with impacts such as survivor’s guilt, depression, PTSD symptoms, physical symptoms, psychic numbing, anger, and suicidal ideation.

- Her analysis and understanding of historical trauma led her in 1992 to create the Brthe Takini Network (now the Takini Institute) in South Dakota.

- Decolonizing psychology calls for the people who have experienced suffering and oppression to be the ones who come up with solutions, and come up with their own psychological theories and understandings.

(1.6) Thinking about decolonization, how may this apply to education? What would a psychology class be like if it were decolonized? Think about the content of the course, as well as how it would be taught. What would this type of course look like or feel like if you were taking it?

Why is there a need for critical consciousness? How can you engage in critical consciousness development?

The primary goal of liberation psychology is to awaken critical consciousness in people. Critical consciousness or conscientization focuses on achieving an in-depth understanding of the world via the exploration, challenging, and changing of the societal, cultural, economic, and political root causes of distress.[22]

Paulo Freire

Conscientization calls for the continuous process of re-examining of societally held “truths” of why structural injustices occur, recognizing patterns of thoughts and behaviors that support and challenge societally held “truths”, using critical and reflective skills to reinterpret and reframe “truths” and dominant narratives, create new “truths” and then if one so chooses, engaging in liberatory social justice action based on the reinterpretation and reframing.

- This approach challenges you to go beyond simply repeating information from your classes and instead develop critical thinking and analytical skills.

-

- For example, in mental health discussions, we often hear that chemical imbalances in the brain cause anxiety and depression. But is this explanation enough? How do factors like poverty, discrimination, or job insecurity contribute to mental distress? Does it matter if someone has access to supportive relationships, stable housing, or adequate healthcare? How might shifting the focus from individual brain chemistry to broader social conditions change the way we understand and address mental health struggles?

- You are encouraged to recognize your ability to shape your own lives and to advocate for social justice.

- You are encouraged to reflect on your education, and critically engage with how it does or does not reflect you and your community’s lives, as well as how it can be used to transform lived realities and systems of oppression.[23]

(1.7) Critical consciousness encourages you to actively question, challenge, and rethink existing theories, while also creating new theories that are relevant to your own lived experiences. One example to consider is how does the field of psychology define “normal” and “abnormal”? What are your thoughts on these concepts?

Some questions that support critical consciousness development:

- Who developed this theory? What population did they base it on?

- “Who benefits from this theory?”

- “Who might be harmed?”

- “Which voices have been left out of this conversation?”

- “Which voices have been left out of the development of this intervention?”

- “Who is the focus of the study?”

- “Who are the ones studying this population?”

- “Why are researchers asking these questions?” “In this way?”

- “Do these theories reflect your lived experiences?”

- “Do these interventions work in your cultural context?”

- “How do these theories and interventions maintain the status quo?”

(1.8) Can you think of some examples of when you have personally engaged in critical consciousness raising? What is a time when you shifted your perspective on something because you engaged with in-depth thinking, reflecting, and learning?

(1.9) Do you think there is a need for critical consciousness development in psychology courses? Why or why not?

So, how might you start this journey of further understanding liberation psychology? How can you and your fellow students apply it to your understanding of psychological theories and experiments?

We start the work of liberation with ourselves, not with a focus on the “other.” We center ourselves, our experiences, and their relationship to systems of family, community, society, and systemic oppression and dominance.

- We explore our intersectional and complex identities and how they influence how we see ourselves, the world around us, and the people in it. When it comes to the question of identity, we use Hall’s framework. Identity helps us answer the question of “Who am I?” Hall wrote that our identities have three levels:

- personal, which are the unique aspects of our identity, like our personality and life experiences

- relational, which refers to our relationship with others, such as connection to family and profession, and

- social, which is our large-scale group membership and refers to membership in groups such as race, gender identity, sexuality, class, ethnicity, religion, geography, disability, and more.

- Our social identities are linked to access to structural power. “Structural Power refers to the ways in which power (such as authority, wealth, and other privileges) is arranged in order to influence the norms of society, institutions, and our interpersonal relationships”.[24] It is what tells us and enforces what is normal. From deciding that working from 9 to 5 from Monday to Friday is the primary way American society will function to deciding that universal healthcare is not possible, structural power defines our reality. These norms do not just happen, they are created by people with power.

Some parts of our identities are marginalized, while other aspects hold power.

As intersectionality theory points out, systems of inequality based on social group membership intersect in ways that create unique dynamics and impacts.

For example, though both of the authors of this workbook are John Jay faculty and hold doctorates, which are examples of educational and job privilege, they still experience the world differently due to differences in race (one is Black and the other is white) and the titles that they hold (one is an Adjunct while the other is Full time faculty). These differences can influence how they are viewed and treated by students and colleagues and impact access to resources.

- Some aspects of our identities are not visible, nevertheless, these aspects still play a pivotal role in how we understand and experience the world and how we show up in all the spaces we inhabit.

- Our identities can show up differently in different contexts. What identities show up in class, with your friends, and walking down the street might be similar or very different.

Oftentimes, if you have identities that are part of the dominant culture, you have the privilege of not having to think about those aspects of identity. You do not wonder if people are treating you differently because of those aspects of your identity. While for those who have marginalized aspects of their identity, they are very connected to the marginalized aspects, because people’s and systems’ reactions to them can be harmful and dangerous. And the body/mind seeks to protect itself.

In this workbook, we encourage you to explore all aspects of your identity, however, there will be an emphasis on exploring social identities as they are the identities that confer power and privilege to some and marginalize and oppress others. Critically engaging with your own identities helps start the process of liberation.

When exploring and reflecting on ourselves and our positionality, as well as when we critically engage with the field of psychology, we encourage you to use aspects of the cultural humility framework in your approach. Cultural humility is “A personal lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture, but one starts with an examination of her/his [or their] own beliefs and cultural identities. Recognition of power dynamics and imbalances, a desire to fix those power imbalances, and to develop partnerships with people and groups who advocate for others.[25] We ask you to explore yourself and the information workbook with openness, curiosity, and awareness of the multiple ways that power operates.

(1.10) Self-Reflection Questions

- Which of your identities are most salient to you?

- Which identities do you think about the least?

- Which of your identities are most salient in your role as a student?

- Which identities do you think about the least as a student?

- How do you tend to participate in groups? Talk more? Listen more?

- What do you need to participate best in the class? What access needs do you have?

- What does/could liberation psychology mean to you?

- What reactions do you have to the quote that begins this workbook?

Individual Activities:

- Read and respond to the Dialogue vs Debate Article

- Approximately 15 minutes

- Identify personal commitments to engaging in group dialogue from a multicultural, curious perspective

- Instructions:

- State or Write: Discussions around culture and multiculturalism (including, and in particular, with respect to race) can be difficult for many reasons, in large part due to individuals’ differences in worldview and cultural assumptions that we all hold. Throughout the course, a goal is to make our discussions productive and respectful, even if we do not agree (maybe especially if we do not agree). To support this goal, please read the article, “The differences between Dialogue and Debate.”

- After reading the article, identify a minimum of 2 points from the dialogue, behaviors that support dialogue, and/or the multicultural communications competencies sections (for example, “I search for strength and value in other’s positions”) that you will commit to implementing throughout the semester, particularly when posting and responding in the discussion board or when discussing course topics with other students. Using “I” statements, write a minimum of 5 sentences about why these two themes are important for you, personally, to implement.

- We will be using the suggestions from this article as a framework for engaging with one another throughout the course.

- Social Identity Wheel with questions

- Approximately 10-20 minutes

- Instructions: Fill out the attached social identity wheel with how you identify for each section (or a question mark if you are unsure). This wheel is for your reference to help you answer the discussion post question, you do NOT need to upload the completed social identity wheel. After you complete the wheel, answer the following questions with a minimum of 5 sentences.

- Answer all the following questions using “I” or “Me” statements.

- Of the identities on the wheel, which one is the most salient, and are you the most aware of day-to-day? Why?

- Which one is the most salient, and are you the most aware of, as a John Jay student? Why?

- Which one are you the least aware of/do you think about the least day to day? Why?

- Which one are you the least aware of/do you think about the least as a John Jay student? Why?

- Do you think any of your identities influence your experience of this class? why or why not?

- You do not need to say how you identify, ie, if you identify as Black for race, you do not need to say that being Black is the most salient identity for you, you can instead say that your race is the most salient.

- Activity on Butterflies

- Example of what gives you butterflies, a poem, and Questions from Shadiya Adid.

Butterflies – A list of things that give you butterflies:

-

-

- When you finally apply for that dream job.

-

-

-

- When you join the bandwagon and invest in your first stock.

-

-

-

- When your friends hype you up in the comments on your new selfie.

-

-

-

- When you get off a plane just before reuniting with your family.

-

-

-

- When you’re “randomly” selected at the airport. They tell you to pat your hijab, then swab for bomb residue on your hands.

-

-

-

- When you cross the border, and they say that you look like a refugee. They’re unsure about your documents. You could be sneaking into their country.

-

-

-

- When a cop car comes along, and despite being innocent, you trace back your steps. Analyze where you might have gone wrong.

-

-

-

- When you enter a store, and you feel this hot heat on the back of your neck. The clerk watches you. For a while, you can’t breathe.

-

-

-

- When you tell a guy you’re married, but he doesn’t see a ring. Ignores the hint. Says you’re a tease.

-

-

-

- When you enter an elevator and the man who was following you does too. The doors close. You can’t leave.

-

Poem:

But then the butterflies fly away.

Almost as soon as they came.

As soon as the cop car moves forward.

And you leave the store.

And you get your luggage back.

You safely make it to your floor.

Hyper-surveillance is something that I wish I could opt out of.

But it’s a part of every day.

Like eating lunch at noon.

Like forgetting to unmute on Zoom.

It’s just a minor inconvenience.

It’s just a part of the Black Muslim girl experience.

For some, stares prompt questions like:

Is there something in my teeth? Is he into me?

For us, it’s more like:

Is it my Blackness today?

Or my Muslim-ness?

Or how easy it would be to take advantage of me?

Fear is a sharp knife that travels up your body until it settles somewhere deep.

Leaving a trail of scars from anxiety.

Like a parasite feeding off negative energy.

Doesn’t hesitate to make everyone your enemy.

Fear is the most abusive warden.

It keeps you caged.

Dares you to escape and then reminds you of your place.

Fear wants to be heard.

Wants to be consoled.

Wants to believe the story that it was told.

And although you’re no criminal.

You’re no victim.

You internalize these roles.

You’re the one that doesn’t belong. Misplaced.

You’re the glitch in the algorithm. A mistake.

So, in order to placate those with more power over you,

You step into respectability.

Minimize anything and everything.

You apologize for your existence.

Take it as betrayal or a survival mechanism.

Conform to the behaviour that they feel entitled to.

That helps them feel safe.

While simultaneously being and feeling unsafe.

But hey, at least the butterflies eventually fly away.

- Discussion Questions

-

- How does the fear of those in power contrast (and interrelate) with the fears expressed by the author?

- When have you felt powerless?

- Write a list of things that have given you “butterflies.”

- Did existing power dynamics (race, gender, class, etc.) exacerbate this powerlessness?

- Did institutions (the education system, the carceral system, the healthcare system, etc.) exacerbate this powerlessness?

-

- While power itself is not necessarily problematic, the ways in which it is structured tend to advance the privileges of one group of people, while devaluing and subjugating others. Can you think of a form of power that is benign in its ‘neutral state’, but problematic when it becomes structured? What enables this structuring to take place?

(1.12) Each person picks a contributor to the field of liberation psychology and then reports back findings to the group.

(1.13) What are your reactions to what you read? What questions do you have? Based on what you have learned in this chapter, what questions do you have and for whom? Are there questions that you have for yourself?

(1.14) Based on the class you are in now, what material would you want covered in/focused on in this class and why?

Closing Activity

- What are a few feelings you are experiencing now?

- What is something you can do to transition yourself from this workbook to what you need to do next?

Chapter Resources

Articles

- Dialogue vs Debate Article

- Mental Health, Oppression and Liberation Article: https://www.rc.org/publication/theory/liberationpolicy/mental_health_jf

- Decolonizing mental health: The importance of an oppression-focused mental health system – Calgary Journal

Websites

- Structural power

- Add all the associations from APA and beyond, and the year started

Videos

- *Music/videos – Dead Prez “These Schools”

- Cultural Humility: People, Principles, and Practices video by creators of the term https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SaSHLbS1V4w&t=450s

- Liberation Psychology panel discussion video: Building a Counseling Psychology of Liberation: Exploring Liberation Principles in Our Own Lives

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BmKYHLnMeYU&t=398s

Handouts:

- Social Identity wheel and definitions-RECREATE

- Critical Thinking Questions-CREATE or find

- Template for “I am poem” -multiple versions

- Oppression

- 10 breathing techniques for stress relief. (2019, April 9). Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/breathing-exercise ↵

- Society of Counseling Psychology, 2021, Building a Counseling Psychology of Liberation section, para 1 ↵

- Bryant-Davis, T. E., & Comas-Díaz, L. E. (2016). Womanist and mujerista psychologies: Voices of fire, acts of courage. American Psychological Association. ↵

- Burton, M., & Guzzo, R. (2020). Liberation psychology: Origins and development. In Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice (p 17-40). American Psychological Association. ↵

- Comas-Díaz, L. E., & Rivera, T. (2020). Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice (pp. xx-314). American Psychological Association. ↵

- What is liberation psychology and what is liberation-based therapy? (n.d.). Liberation-Based Therapy LCSW, PLLC. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://www.liberationbasedtherapy.com/blog/what-is-liberation-psychology-and-what-is-liberation-based-therapy-wmc5e ↵

- David, E. J. R., & Derthick, A. O. (2018). The psychology of oppression. Springer Publishing Co. ↵

- Denneny, M. Gay Politics: Sixteen Propositions. In Blasius, M., & Phelan, S. (Eds) (1997). We are everywhere: a historical sourcebook of gay and lesbian politics. Routledge. ↵

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–48). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. ↵

- Eugenics on the farm: Lewis terman. (2019, November 6). https://stanforddaily.com/2019/11/06/eugenics-on-the-farm-lewis-terman/ ↵

- Furumoto, L., & Scarborough, E. (1996). Placing women in the history of psychology: The first American women psychologists. American Psychologist, 41(1), 35-42. ↵

- Furumoto, L., & Scarborough, E. (1996). Placing women in the history of psychology: The first American women psychologists. American Psychologist, 41(1), 35-42. ↵

- Furumoto, L., & Scarborough, E. (1996). Placing women in the history of psychology: The first American women psychologists. American Psychologist, 41(1), 35-42. ↵

- Weick, A., Rapp, C., Sullivan, W. P., & Kisthardt, W. (1989). A strengths perspective for social work practice. Social work, 34(4), 350-354. ↵

- Singh, A. A., Parker, B., Aqil, A. R., & Thacker, F. (2020). Liberation psychology and LGBTQ+ communities: Naming colonization, uplifting resilience, and reclaiming ancient his-stories, her-stories, and t-stories. In Liberation psychology: Theory, method, practice, and social justice (pp. 3-13). American Psychological Association. ↵

- Mullan, J. (2023). Decolonizing therapy: Oppression, historical trauma, and politicizing your practice. WW Norton & Company. ↵

- How Many Different Countries Have Colonies? | Infoplease. (n.d.). Www.infoplease.com. https://www.infoplease.com/diplomacy/how-many-countries ↵

- David, E. J. R., & Derthick, A. O. (2018). The psychology of oppression. Springer Publishing Co. ↵

- Lander, E. (2000). Eurocentrism and colonialism in Latin American social thought. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(3), 519-532. ↵

- Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: Contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural studies, 21(2-3), 240-270. ↵

- Adams, G., Gómez Ordóñez, L., Kurtiş, T., Molina, L. E., & Dobles, I. (2017). Notes on decolonizing psychology: From one special issue to another. South African Journal of Psychology, 47(4), 531-541. ↵

- Freire, P. (1972). Education: domestication or liberation?. Prospects, 2(2), 173-181. ↵

- Chung & Bemak, 2012, Bemak, F., & Chung, R. C. Y. (2012). Culturally oriented psychotherapy with refugees. In Handbook of culture, therapy, and healing (pp. 141-152). Routledge. ↵

- Aidid, S. (2022). Structural power. https://doi.org/10.22215/stkt/as17 ↵

- Yeager, Katherine A., and Susan Bauer-Wu. 2013. "Cultural Humility: Essential Foundation For Clinical Researchers". Applied Nursing Research 26 (4): 251-256 Zapata, 2020 ↵