Chapter 9.3: The Role of Commercial Banks

9.3 The Role of Commercial Banks and The Creation of Money

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how banks act as intermediaries between savers and borrowers

- Evaluate the relationship between banks, savings and loans banks, and credit unions

- Utilize the money multiplier formulate to determine how banks create money

- Analyze and create T-account balance sheets

- Evaluate the risks and benefits of money and banks

Banks: Definition & Purpose

Banks are depository institutions that accept deposits and make loans. Banks make it far easier for a complex economy to carry out the extraordinary range of transactions that occur in goods, labor, and financial capital markets. Imagine for a moment what the economy would be like if everybody had to make all payments in cash. When shopping for a large purchase or going on vacation you would have to carry hundreds of dollars in a pocket or purse. Even small businesses would need stockpiles of cash to pay workers and to purchase supplies. A bank allows people and businesses to store their money in either a checking account or savings account, for example, and then withdraw this money as needed through the use of a direct withdrawal, writing a check, or using a debit card.

Banks as Financial Intermediaries

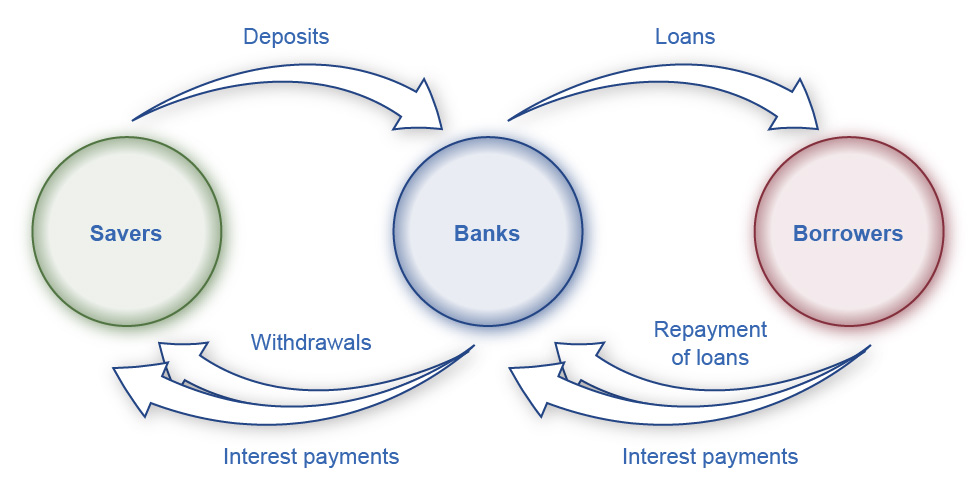

An “intermediary” is one who stands between two other parties. Banks are a critical intermediary in what we call the payment system, which helps an economy exchange goods and services for money or other financial assets. Banks are also a financial intermediary—that is, an institution that operates between a saver who deposits money in a bank and a borrower who receives a loan from that bank. Those with money they want to save can store their money in a bank rather than look for an individual who is willing to borrow it from them and then repay them at a later date. And those who want to borrow money can go directly to a bank rather than trying to find someone to lend them cash. Transaction costs are the costs associated with finding a lender or a borrower for this money. Thus, banks lower transactions costs and act as financial intermediaries—they bring savers and borrowers together. Along with making transactions much safer and easier, banks also play a key role in creating money. Banks aren’t the only institutions that serve as financial intermediaries. Other financial intermediaries include other institutions in the financial market such as insurance companies and pension funds, but we will not include them in this discussion because they are not depository institutions, which are institutions that accept money deposits and then use these to make loans. All the deposited funds mingle in one big pool, which the financial institution then lends. Figure 11.3 illustrates the position of banks as financial intermediaries, with deposits flowing into a bank and loans flowing out. Of course, when banks make loans to firms, the banks will try to funnel financial capital to healthy businesses that have good prospects for repaying the loans, not to firms that are suffering losses and may be unable to repay.

“Banks as Financial Intermediaries” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 9.3 Banks as Financial Intermediaries Banks act as financial intermediaries because they stand between savers and borrowers. Savers place deposits with banks, and then receive interest payments and withdraw money. Borrowers receive loans from banks and repay the loans with interest. In turn, banks return money to savers in the form of withdrawals, which also include interest payments from banks to savers.

A Bank’s Balance Sheet

A balance sheet is an accounting tool that lists assets and liabilities. An asset is something of value that you own. For example, you can use the cash you own to pay your tuition. If you own a home, this is also an asset. A liability is a debt or something you owe. Many people borrow money to buy homes. In this case, a home is the asset, but the mortgage is the liability. Net worth is the asset value minus how much is owed (the liability).

A bank’s balance sheet operates in much the same way.

Assets: bank assets encompass a variety of items such as buildings, furniture, and computer equipment. However, the most significant assets for banks are loans, which are extended by the bank to both households and businesses. Other assets are bank reserves, the amount of cash held by the bank. By law the Federal Reserve mandates that banks maintain a portion of their deposits as reserves, which are referred to as bank reserves.

Liabilities: refer to what the bank owes to others, essentially its debts. The primary liabilities for banks are customer deposits.

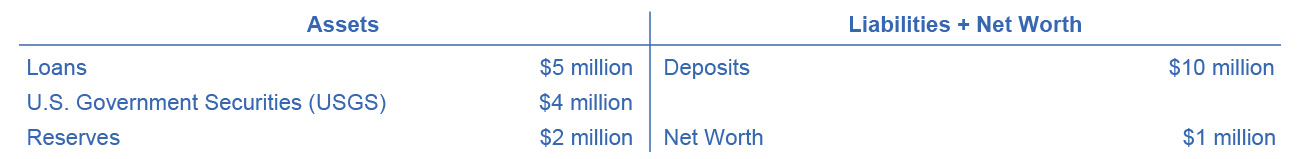

Table 9.2 illustrates a hypothetical and simplified balance sheet for a commercial bank. T- account is the two-column format of the balance sheet, with the T-shape formed by the vertical line down the middle and the horizontal line under “Assets” and “Liabilities”. Each side must balance.

“A Balance Sheet for the Safe and Secure Bank” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Table 9.2 A Balance Sheet for a commercial bank

For a bank, the assets are the financial instruments that either the bank is holding (its reserves) or those instruments where other parties owe money to the bank—like loans made by the bank, and U.S. Government Securities, such as U.S. treasury bonds and bills purchased by the bank. Liabilities are what the bank owes to others. Specifically, the bank owes any deposits made in the bank to those who have made them. The net worth of the bank is the total assets minus total liabilities. Net worth is included on the liabilities side to have the T account balance to zero. For a healthy business, net worth will be positive. For a bankrupt firm, net worth will be negative. In either case, on a bank’s T-account, assets will always equal liabilities plus net worth.

When bank customers deposit money into a checking account, savings account, or a certificate of deposit, the bank views these deposits as liabilities. After all, the bank owes these deposits to its customers, when the customers wish to withdraw their money. In the example in Table 9.2, the example of the commercial bank above it holds $10 million in deposits.

The Reserve Required Ratio – is the percent of all deposits that banks must keep aside as reserves by law available for customer withdrawals.

How Banks Create Money

Banks create money by making loans. However, this ability of creating money is controlled through the reserve requirement ratio which is set by the Federal Reserve System (more about this topic later).

Money Creation by a Single Bank

Originally, banks were established primarily for safekeeping purposes. Individuals would entrust their money to a bank, which would then safeguard all deposits in its vault (= bank reserves) without engaging in lending activities. Let’s consider a hypothetical bank named Bank One, which operates solely as a depository institution. Jonathan receives $1,000 from his grandmother as a birthday gift and decides to deposit it at Bank One. Upon receiving Jonathan’s deposit, Bank One records it as a liability since the funds belong to Jonathan, not the bank itself. The T-account balance sheet for Bank One, holding all deposits in its vaults, is outlined in the table below. At this stage, Bank One is simply storing money for depositors. In this simplified scenario, Bank One does not generate any interest income from loans and is unable to offer interest rates to depositors.

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: $1,000 |

Deposits: $1,000 |

“Singleton Bank’s Balance Sheet: Receives $10 million in Deposits” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Table 9.3 Bank One’s Balance Sheet: Receives $,1000 in Deposits

Let’s assume now that The Federal Reserve set a reserve requirement ratio of 10%, meaning, Bank One must keep 10% of its deposits as reserves ($100). After setting aside this $100, Bank One can lend the remaining $900 to various borrowers. By loaning the $900 and charging interest, it will be able to make interest payments to depositors and earn income from the interest for Bank One. This way, instead of becoming a mere place to store deposits, Bank One can serve as a financial intermediary between savers and borrowers and create money for the bank in the process.

Imagine if Bank One were to lend $900 to Hank’s Bakery. The mandatory reserve requirement and the ability to make loans, in this case, to Hank’s Bakery, would alter Bank One’s balance sheet, as Table 9.4 shows. Bank One’s assets have changed. It now has $100 n in reserves and a loan of $900 to Hank’s Bakery. The bank still has $1,000 in deposits.

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: $100 |

Deposits: $1,000 |

|

Loans: $900 |

|

Table 9.4 Bank One’s Balance Sheet: 10% Reserves, One Round of Loans

After Bank One lends $900 to Hank’s Bakery it records the loan by making an entry on the it’s balance sheet to indicate that it has made a loan. This loan is an asset because it will generate interest income for the bank. Meanwhile Hank, the owner of Hank’s Bakery deposits the $900 loan in his regular checking account with Bank Two. The deposits at Bank Two rise by $900 and its reserves also rise by $900, as Table 9.5 shows. Bank Two must hold 10% of additional deposits as required reserves but is free to loan out the rest.

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: $900 |

Deposits: $900 |

Table 9.5 Bank Two Balance Sheet

Making loans that are deposited into a demand deposit account increases the M1 money supply. Remember that the definition of M1 money includes checkable (demand) deposits, which one can easily use as a medium of exchange to buy goods and services. Notice that the money supply is now $1,900 million: $1,000 million Jonathan’s deposits at Bank One and $900 in deposits at Bank Two.

Now, Bank Two must hold only 10% as required reserves ($90) but can lend out the other 90% ($810) in a loan to Jack’s Delivery Business a Table 9.6 shows.

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: $90 |

Deposits: $900 |

|

Loans: $810 |

|

Table 9.6 Bank Two Balance Sheet

If Jack’s deposits the loan in its checking account at Bank Three, the money supply just increased by an additional $810, as Table 9.7 shows.

|

Assets |

Liabilities |

|

Reserves: $810 |

Deposits: $810 |

Table 9.7 Bank Three Balance Sheet

The action of Jonathan’s original deposit of $1,000 in the bank, created a loan of $900 + a loan of $810 + $729 and more…. This process will continue, the loans getting smaller but essentially creating more loans thus more money. How is this money creation possible? It is possible because there are multiple banks in the financial system, they are required to hold only a fraction of their deposits, and loans end up deposited in other banks, which increases deposits and, in essence, the money supply.

The Money Multiplier and a Multi-Bank System

In a system with multiple banks, Bank One deposited the initial excess reserve amount that it decided to lend to Hank’s Bakery into Bank Two, which is free to loan out $810. If all banks loan out their excess reserves, the money supply will expand. In a multi-bank system, institutions determine the amount of money that the system can create by using the money multiplier. This tells us by how many times a loan will be “multiplied” as it is spent in the economy and then re-deposited in other banks.

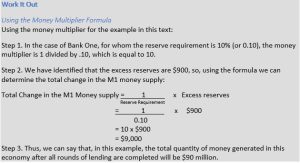

Fortunately, a formula exists for calculating the total of these many rounds of lending in a banking system. The money multiplier formula is:

We then multiply the money multiplier by the change in excess reserves to determine the total amount of M1 money supply created in the banking system. See the Work it Out feature to walk through the multiplier calculation.

Run on a Bank

A run on a bank occurs when a large number of customers withdraw their deposits from a bank within a short period, typically due to concerns about the bank’s solvency or stability. This sudden surge in withdrawals can deplete the bank’s reserves, making it difficult for the bank to meet the demands of all its depositors. Runs on banks can lead to liquidity crises and, in severe cases, may result in the bank’s failure.

Today, to deter a bank run, the Federal Reserve mandates banks to maintain a reserve ratio, necessitating that a specified percentage of each deposit be set aside. Additionally, in the United States, deposits of up to $250,000 are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Bank runs will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 12.2.

Cautions about the Money Multiplier

The money multiplier will depend on the proportion of reserves that the Federal Reserve Band requires banks to hold. Additionally, a bank can also choose to hold extra reserves. Banks may decide to vary how much they hold in reserves for two reasons: macroeconomic conditions and government rules. When an economy is in recession, banks are likely to hold a higher proportion of reserves because they fear that customers are less likely to repay loans when the economy is slow. The Federal Reserve may also raise or lower the required reserves held by banks as a policy move to affect the quantity of money in an economy, as the unit on Monetary Policy will discuss.

The process of how banks create money shows how the quantity of money in an economy is closely linked to the quantity of lending or credit in the economy. All the money in the economy, except for the original reserves, is a result of bank loans that institutions repeatedly re-deposit and loan.

Finally, the money multiplier depends on people re-depositing the money that they receive in the banking system. If people instead store their cash in safe-deposit boxes or in shoeboxes hidden in their closets, then banks cannot recirculate the money in the form of loans. Central banks have an incentive to assure that bank deposits are safe because if people worry that they may lose their bank deposits, they may start holding more money in cash, instead of depositing it in banks, and the quantity of loans in an economy will decline. Low-income countries have what economists sometimes refer to as “mattress savings,” or money that people are hiding in their homes because they do not trust banks. When mattress savings in an economy are substantial, banks cannot lend out those funds and the money multiplier cannot operate as effectively. The overall quantity of money and loans in such an economy will decline.

Money and Banks—Benefits and Dangers

Money and banks are marvelous social inventions that help a modern economy to function. Compared with the alternative of barter, money makes market exchanges vastly easier in goods, labor, and financial markets. Banking makes money still more effective in facilitating exchanges in goods and labor markets. Moreover, the process of banks making loans in financial capital markets is intimately tied to the creation of money.

However, the extraordinary economic gains that are possible through money and banking also suggest some possible corresponding dangers. If banks are not working well, it can sets off a decline in the convenience and safety of transactions throughout the economy. If the banks are under financial stress, because of a widespread decline in the value of their assets, loans may become far less available, which can deal a crushing blow to sectors of the economy that depend on borrowed money like business investment, home construction, and car manufacturing. The 2008–2009 Great Recession illustrated this pattern.

Bring It Home

The Many Disguises of Money: From Cowries to Crypto

The global economy has come a long way since it started using cowrie shells (shells from snails) as currency. We have moved away from commodity and commodity-backed paper money to fiat currency. As technology and global integration increases, the need for paper currency is diminishing, too. Every day, we witness the increased use of debit and credit cards.

The latest creation and a new form of money is cryptocurrency. Cryptocurrency is digital currency that is not controlled by any single entity, such as a company or country. In this sense, it is not a fiat currency because it is not issued by a central bank and is not necessarily supported by governments as legal tender. Instead, transactions and ownership are maintained in a decentralized manner, and the value (vis-à-vis, say, the U.S. dollar) is determined primarily by market forces—i.e., supply and demand. Governments can affect the value of a cryptocurrency by regulating its use within their country’s boundaries, but in the end, the price of a cryptocurrency comes down to supply and demand. Cryptocurrencies have come a long way since 2009 when Bitcoin was first invented, and the recent two to three years has seen an explosion of different cryptocurrencies being used across the globe.

It is important to note that in order to be considered as money, cryptocurrency still needs to satisfy the three requirements: it needs to be valid as a store of value, it needs to be valid as a unit of account, and it must be able to be used as a medium of exchange. While the first two of these requirements can be satisfied easily by expressing the currency in terms of another, such as the U.S. dollar, and through its secure ownership rules, its use as a medium of exchange—to be used to buy and sell goods and services—is more complicated. While cryptocurrencies are used in many illicit transactions, it is less common to see them accepted as forms of payment for regular things like groceries or your rent.

Bitcoin is the most popular cryptocurrency, and thus the one most likely to be considered real money since it can be used to purchase the most goods and services. Other popular cryptocurrencies as of early 2022 (in terms of trade volume) are Ethereum and Binance Coin. Many other cryptocurrencies exist, but their more widespread adoption as a medium of exchange is yet to be seen.

This chapter is a remixed version of the chapters 14.3 The Role of Banks and 14.4 How Banks Create Money in Principles of Macroeconomics 3e by OpenStax, published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Other additions and modifications have been made in accord with the style, structure, and audience of this guide.