Chapter 10.4 Monetary Policy and Economic Outcomes

10.4 Monetary Policy and Economic Outcomes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how monetary policy impacts interest rates and GDP

Let’s start by summarizing the two scenarios in which the Federal Reserve implements monetary policy. In Scenario A, characterized by recession and high unemployment, the Fed employs expansionary monetary measures. In Scenario B, when the economy is growing rapidly and there is a risk of overheating leading to inflation, the Fed adopts contractionary monetary policy.

Monetary policy that lowers interest rates and stimulates borrowing is an expansionary monetary policy or loose monetary policy. Conversely, a monetary policy that raises interest rates and reduces borrowing in the economy is a contractionary monetary policy or tight monetary policy. This module will discuss how expansionary and contractionary monetary policies affect interest rates and GDP, and how such policies will affect macroeconomic goals like unemployment and inflation.

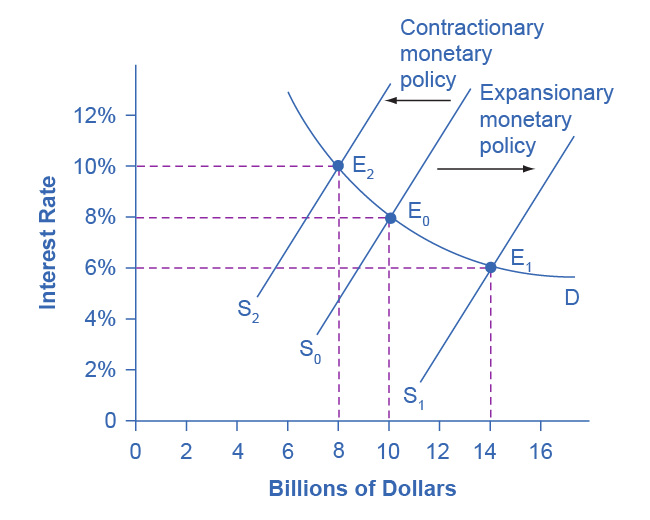

The Effect of Monetary Policy on Interest Rates

Consider the market for loanable bank funds in Figure 10.4. Figure 10.4 illustrates the relationship between interest rates and the amount of loans. The higher the interest rates, the lower of quantity of loans demanded, however, the higher the interest rates, the higher the quantity supplied of loans. The original equilibrium (E0) occurs at an 8% interest rate and a quantity of funds loaned and borrowed of $10 billion. An expansionary monetary policy will shift the supply of loanable funds to the right from the original supply curve (S0) to S1, leading to an equilibrium (E1) with a lower 6% interest rate and a quantity $14 billion in loaned funds. Conversely, a contractionary monetary policy will shift the supply of loanable funds to the left from the original supply curve (S0) to S2, leading to an equilibrium (E2) with a higher 10% interest rate and a quantity of $8 billion in loaned funds.

“Monetary Policy and Interest Rates” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 10.4 Monetary Policy and Interest Rates The original equilibrium occurs at E0. An expansionary monetary policy will shift the supply of loanable funds to the right from the original supply curve (S0) to the new supply curve (S1) and to a new equilibrium of E1, reducing the interest rate from 8% to 6%. A contractionary monetary policy will shift the supply of loanable funds to the left from the original supply curve (S0) to the new supply (S2), and raise the interest rate from 8% to 10%.

How does the Fed “raise” interest rates? When describing the Fed’s monetary policy actions, it is common to hear that the Fed “raised interest rates” or “lowered interest rates.” We need to be clear about this: more precisely, through open market operations the Feds end up causing the target rate known as the fed fund rate to increases or to decreases. Depending on whether the Fed engages in expansionary or contractionary monetary policy, the supply curve of loans will ether shift to the right or to the left. If the Fed engages in expansionary policy, the supply of loans will shift to the right, and if the demand for loans remains unchanged, this will cause the benchmark interest rate to decline. In Figure 10.4 you can see the money supply curve shifting to the right from S0 to S1 causing the interest rates to drop from 8% to 6%. However, if the Fed engages in contractionary monetary policy, In Figure 12.4 the money supply curve will shift to the left from S0 to S2, this causes interest rates to increase from original 8% to 10%.

Of course, financial markets display a wide range of interest rates, representing borrowers with different risk premiums and loans that they must repay over different periods of time. In general, when the federal funds rate drops substantially, other interest rates drop too, and when the federal funds rate rises, other interest rates rise. However, a fall or rise of one percentage point in the federal funds rate—which you may remember is the interest rate banks pay for borrowing money from the Fed overnight—will typically have an effect of less than one percentage point on a 30-year bank loan to purchase a house or a three-year loan to purchase a car. Monetary policy can push the entire spectrum of interest rates higher or lower, but the forces of supply and demand in those specific markets for lending and borrowing set the specific interest rates.

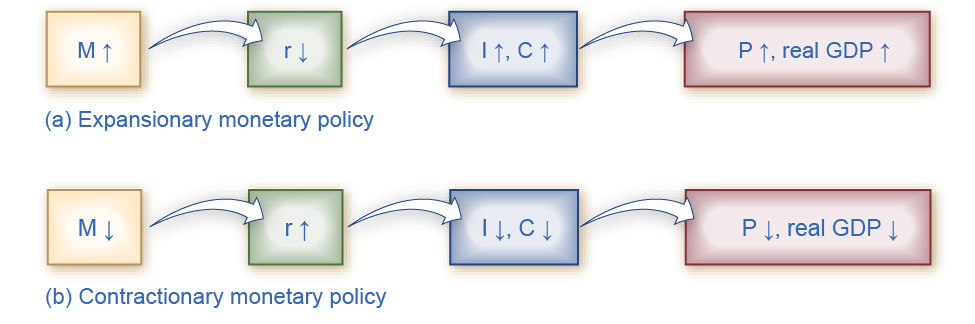

The Effect of Monetary Policy on GDP

Monetary policy affects interest rates and the available quantity of loanable funds, which in turn affects several components of the overall economy. Tight or contractionary monetary policy that leads to higher interest rates and a reduced quantity of loanable funds will reduce two components of GDP: investment by firms and consumption by households. Business investment will decline because it is less attractive for firms to borrow money when interest rates are high, and even firms that have money will notice that, with higher interest rates, it is relatively more attractive to put those funds in a financial investment than to make an investment in physical capital. In addition, higher interest rates will discourage consumer borrowing for big-ticket items like houses and cars. Conversely, loose, or expansionary monetary policy, that leads to lower interest rates and a higher quantity of loanable funds will tend to increase business investment and consumer borrowing for big-ticket items.

If the economy is in a recession and is experiencing high unemployment, expansionary monetary policy can help the economy return to its potential GDP.

Conversely, if an economy is growing too fast and is experiencing inflation, a contractionary monetary policy can reduce the inflationary pressures for a rising price level and lower inflation.

These scenarios suggest that monetary policy should be countercyclical; that is, it should act to counterbalance the business cycles of economic downturns and upswings. The Fed should loosen monetary policy when a recession has caused unemployment to increase and tighten it when inflation threatens. Of course, countercyclical policy does pose a danger of overreaction. If loose monetary policy seeking to end a recession goes too far, it might trigger inflation. If tight monetary policy seeking to reduce inflation goes too far, it might cause a recession to begins Figure 10.5 (a) summarizes the chain of effects that connect loose and tight monetary policy to changes in output and the price level.

“The Pathways of Monetary Policy” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 10.5 The Pathways of Monetary Policy In the above illustration, M stands for Monetary Supply, r stands for Interest Rate, C stands for Consumption and P stands for Price. (a) In expansionary monetary policy the central bank causes the supply of money and loanable funds to increase, which lowers the interest rate, stimulating additional borrowing for investment and consumption causing GDP to increase. The result is a higher price level and, at least in the short run, higher real GDP. (b) In contractionary monetary policy, the central bank causes the supply of money and credit in the economy to decrease, which raises the interest rate, discouraging borrowing for investment and consumption, causing GDP to slowdown. The result is a lower price level and, at least in the short run, lower real GDP.

This chapter is a remixed version of the chapter 15.4 Monetary Policy and Economic Outcomes in Principles of Macroeconomics 3e by OpenStax, published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Other additions and modifications have been made in accord with the style, structure, and audience of this guide.