Chapter 5.2: Productivity and Growth

5.2 Labor Productivity and Economic Growth

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the role of labor productivity in promoting economic growth

- Analyze the sources of economic growth using the aggregate production function

- Measure an economy’s rate of productivity growth

- Evaluate the power of sustained growth

Let’s revisit some key definitions:

Capital refers to anything produced and used as input to create other goods and services. It encompasses tangible assets like buildings and machines, as well as intangible assets like knowledge and skills acquired through education and training, known as human capital.

Example: Consider a simple economy where capital consists of machines and labor of workers. With 6 machines and 60 workers working 40 hours per week, each machine produces 50 units per month, resulting in a total output (GDP) of 300 units.

What can be done to increase output (or GDP)?

To increase output in this economy, several strategies can be employed:

First, increase the number of workers: Adding 12 more workers leads to 2 additional workers per machine, increasing production. Second, add more machines. And third, extend the workweek to 45 hours from 40 hours.

Output can be enhanced through an increase in capital per worker, a rise in the number of workers, or an extension of labor time.

However, there are two more options, without increasing number of machines or workers.

Improve the quality of workers through education and training can enable workers to be more productive with the same machines, and physical fitness can contribute to increased efficiency.

Finally, upgrade the quality of machines: newer technology, such as faster computers and the Internet, can significantly boost productivity. For instance, internet access facilitates quicker research, as seen in a bank where statistics can be retrieved faster than traditional methods.

In summary, output can be increased by having (1) more workers, (2) enhancing skills per worker, (3) increasing the number of machines, (4) improving the speed of machines, and (5) extending working hours.

Productivity, defined as the ratio of total output to the total number of worker hours, is expressed as output per worker. The long-term upward trend in productivity is attributed to increased capital per worker and advancements in the quality of both workers and machines.

Sustained long-term economic growth comes from increases in worker productivity, which essentially means how well we do things. In other words, how efficient is your nation with its time and workers? Labor productivity is the value that each employed person creates per unit of their input. The easiest way to comprehend labor productivity is to imagine a Canadian worker who can make 10 loaves of bread in an hour versus a U.S. worker who in the same hour can make only two loaves of bread. In this fictional example, the Canadians are more productive. More productivity essentially means you can do more in the same amount of time. This in turn frees up resources for workers to use elsewhere.

What determines how productive workers are? The answer is intuitive. The first determinant of labor productivity is human capital. Human capital is the accumulated knowledge (from education and experience), skills, and expertise that the average worker in an economy possesses. Typically, the higher the average level of education in an economy, the higher the accumulated human capital and the higher the labor productivity.

The second factor that determines labor productivity is technological change. Technological change is a combination of invention—advances in knowledge—and innovation, which is putting those advances to use in a new product or service. For example, the transistor was invented in 1947. It allowed us to miniaturize the footprint of electronic devices and use less power than the tube technology that came before it. Innovations since then have produced smaller and better transistors that are ubiquitous in products as varied as smart-phones, computers, and escalators. Developing the transistor has allowed workers to be anywhere with smaller devices. People can use these devices to communicate with other workers, measure product quality or do any other task in less time, improving worker productivity.

Now that we have explored the determinants of worker productivity, let’s turn to how economists measure economic growth and productivity.

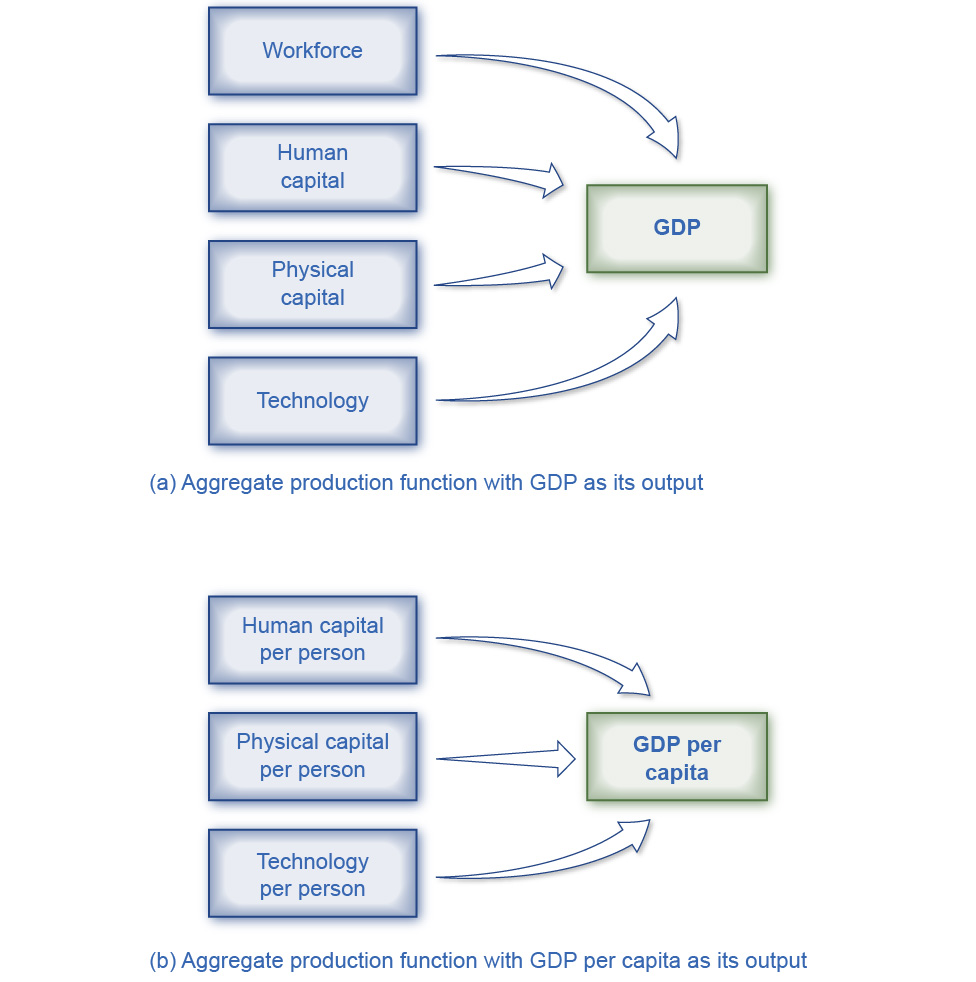

The four determinants of out pout growth (=GDP growth)

“Aggregate Production Functions” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 5.1 Determinants of GDP growth and GDP per person growth.

Measuring Productivity

An economy’s rate of productivity growth is closely linked to the growth rate of its GDP per capita, although the two are not identical. For example, if the percentage of the population who holds jobs in an economy increases, GDP per capita will increase but the productivity of individual workers may not be affected. Over the long term, the only way that GDP per capita can grow continually is if the productivity of the average worker rises or if there are

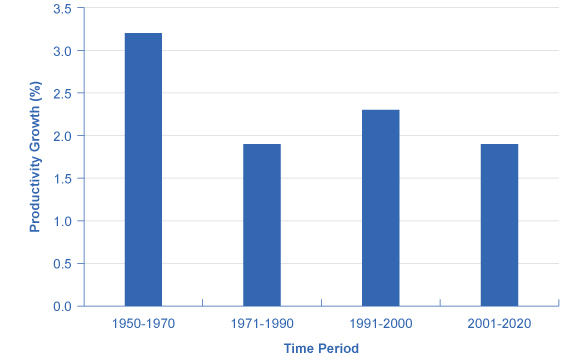

“Productivity Growth Since 1947” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 5.2 Productivity Growth Since 1947 U.S. growth in worker productivity was very high between 1947 and 1973. It then declined to lower levels in the later 1970s and the 1980s. The late 1990s and early 2000s saw productivity rebound, but then productivity sagged a bit between 2001 and 2020. Some think the productivity rebound of the late 1990s and early 2000s marks the start of a “new economy” built on higher productivity growth, but we cannot determine this until more time has passed. (Source: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.)

The “New Economy” Controversy

In recent years a controversy has been brewing among economists about the resurgence of U.S. productivity in the second half of the 1990s. One school of thought argues that the United States had developed a “new economy” based on the extraordinary advances in communications and information technology of the 1990s. The most optimistic proponents argue that it would generate higher average productivity growth for decades to come. The pessimists, alternatively, argue that even five or ten years of stronger productivity growth does not prove that higher productivity will last for the long term. It is hard to infer anything about long-term productivity trends during the later part of the 2000s, because the steep 2008-2009 recession, with its sharp but not completely synchronized declines in output and employment, complicates any interpretation. While productivity growth was high in 2009 and 2010 (around 3%), it has slowed down over the last decade.

Productivity growth is also closely linked to the average level of wages. Over time, the amount that firms are willing to pay workers will depend on the value of the output those workers produce. If a few employers tried to pay their workers less than what those workers produced, then those workers would receive offers of higher wages from other profit-seeking employers. If a few employers mistakenly paid their workers more than what those workers produced, those employers would soon end up with losses. In the long run, productivity per hour is the most important determinant of the average wage level in any economy.

This chapter is a revised version of chapter 7.2 Labor Productivity and Economic Growth by in Principles of Macroeconomics 3e by OpenStax, published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Other additions and modifications have been made in accord with the style, structure, and audience of this guide.