Chapter 4.2: Nominal vs. Real GDP

4.2 Adjusting Nominal Values to Real Values

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Contrast nominal GDP and real GDP

- Explain GDP deflator

- Calculate real GDP based on nominal GDP values

Nominal GDP represents the total value of goods and services produced in an economy at current prices. However, relying on nominal GDP as a measure of production has limitations, as it may give a misleading impression of growth, merely reflecting price increases. Real GDP, on the other hand, accounts for changes in prices, providing a more accurate measure of actual output.

Consider an example: In Year 1, a company contributes $50k to GDP by producing 5 cars valued at $10k each. In Year 2, its contribution increases to $60k. Without adjusting for price changes, it’s challenging to determine if the company produced more cars or simply experienced price inflation. By calculating real GDP, which removes the impact of price fluctuations, we gain insight into actual output changes.

To calculate real GDP and mitigate the influence of price variations, various methods exist. Traditionally, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) used a base year, such as 2000, to convert nominal GDP into constant prices and assess output changes. However, this approach has drawbacks, as it maintains the weights assigned to consumption, investment, government, and trade from the base year, potentially leading to inaccuracies over time. Additionally, international comparisons become problematic when different countries use distinct base years. The BEA now employs a more complex formula to address these concerns.

Converting Nominal to Real GDP

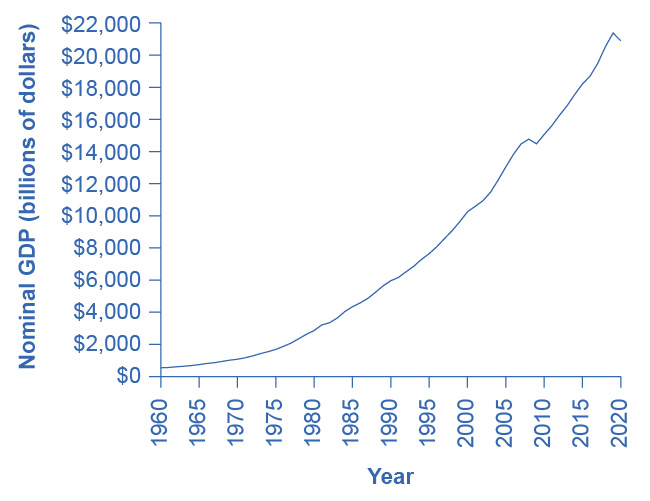

Table 4.3 shows U.S. GDP at five-year intervals since 1960 in nominal dollars; that is, GDP measured using the actual market prices prevailing in each stated year. Figure 4.3 also reflects this data in a graph.

|

Year |

Nominal GDP (billions of dollars) |

GDP Deflator (2005 = 100) |

|

1960 |

542.4 |

16.6 |

|

1965 |

742.3 |

17.8 |

|

1970 |

1,073.3 |

21.7 |

|

1975 |

1,684.9 |

29.8 |

|

1980 |

2,857.3 |

42.2 |

|

1985 |

4,339.0 |

54.5 |

|

1990 |

5,963.1 |

63.6 |

|

1995 |

7,639.7 |

71.8 |

|

2000 |

10,251.0 |

78.0 |

|

2005 |

13,039.2 |

87.5 |

|

2010 |

15,049.0 |

96.2 |

|

2015 |

18,206.0 |

10.47 |

|

2020 |

20,893.7 |

113.6 |

“U.S. Nominal GDP and the GDP Deflator” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Table 4.3 U.S. Nominal GDP and the GDP Deflator (Source: https://apps.bea.gov/itable/index.cfm, Table 1.1.5 and Table 1.1.9)

“U.S. Nominal GDP, 1960–2020” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 4.3 U.S. Nominal GDP, 1960–2020 Nominal GDP values have risen exponentially from 1960 through 2020, according to the BEA.

If an unwary analyst compared nominal GDP in 1960 to nominal GDP in 2010, it might appear that national output had risen by a factor of more than 38 over this time (that is, GDP of $20.9 trillion in 2020 divided by GDP of $543 billion in 1960 = 38). This conclusion would be highly misleading. Recall that we define nominal GDP as the quantity of every final good or service produced multiplied by the price at which it was sold, summed up for all goods and services. In order to see how much production has actually increased, we need to extract the effects of higher prices on nominal GDP. We can easily accomplish this using the GDP deflator.

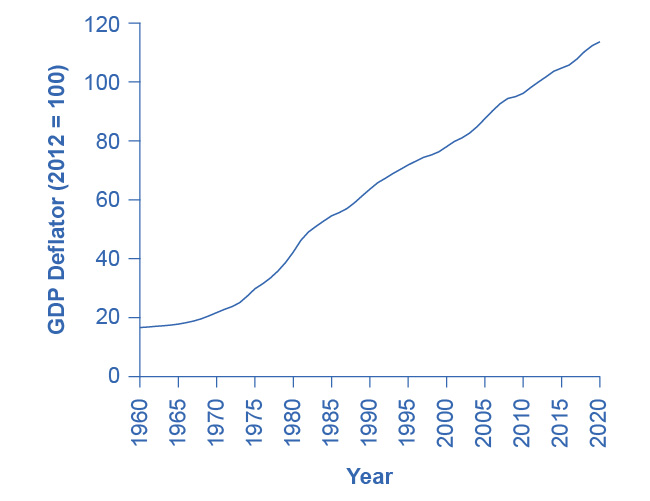

The GDP deflator is a price index measuring the average prices of all final goods and services included in the economy. We explore price indices in detail and how we compute them in the OpenStax textbook Inflation, but this definition will do in the context of this chapter. Table 4.4 provides the GDP deflator data and Figure 4.4 shows it graphically.

“U.S. GDP Deflator, 1960–2020” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 4.4 U.S. GDP Deflator, 1960–2020 Much like nominal GDP, the GDP deflator has risen exponentially from 1960 through 2010. (Source: BEA https://apps.bea.gov/itable/index.cfm, Table 1.1.9)

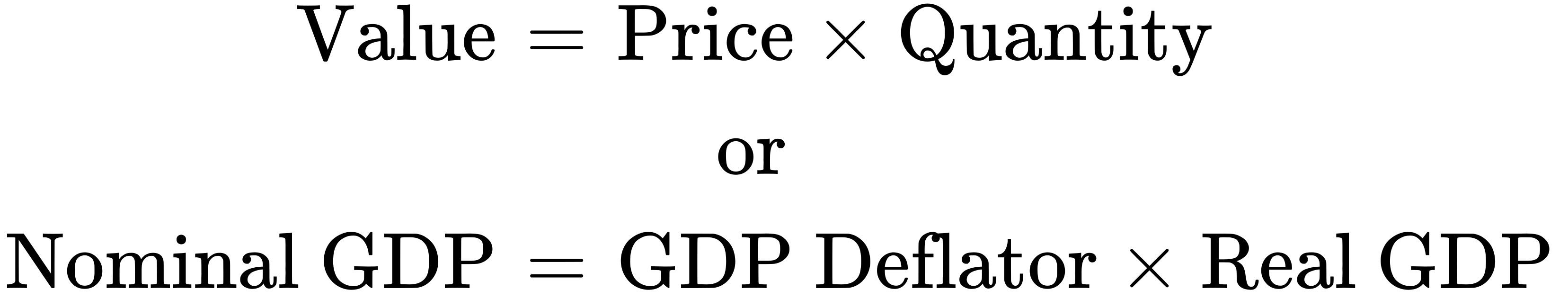

Figure 4.4 shows that the price level has risen dramatically since 1960. The price level in 2020 was seven times higher than in 1960 (the deflator for 2020 was 113 versus a level of 17 in 1960). Clearly, much of the growth in nominal GDP was due to inflation, not an actual change in the quantity of goods and services produced, in other words, not in real GDP. Recall that nominal GDP can rise for two reasons: an increase in output, and/or an increase in prices. What is needed is to extract the increase in prices from nominal GDP so as to measure only changes in output. After all, the dollars used to measure nominal GDP in 1960 are worth more than the inflated dollars of 2020—and the price index tells exactly how much more. This adjustment is easy to do if you understand that nominal measurements are in value terms, where

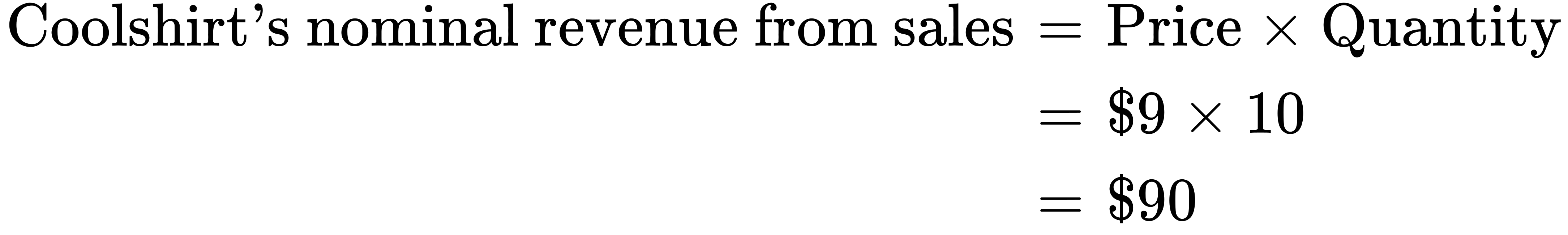

Let’s look at an example at the micro level. Suppose the t-shirt company, Coolshirts, sells 10 t-shirts at a price of $9 each.

Then,

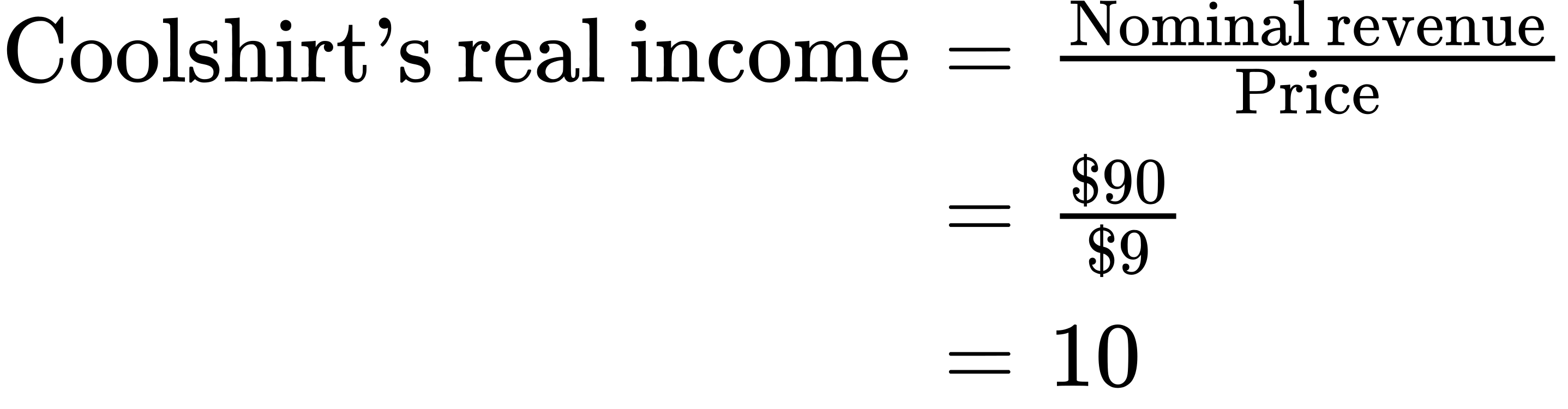

In other words, when we compute “real” measurements we are trying to obtain actual quantities, in this case, 10 t-shirts.

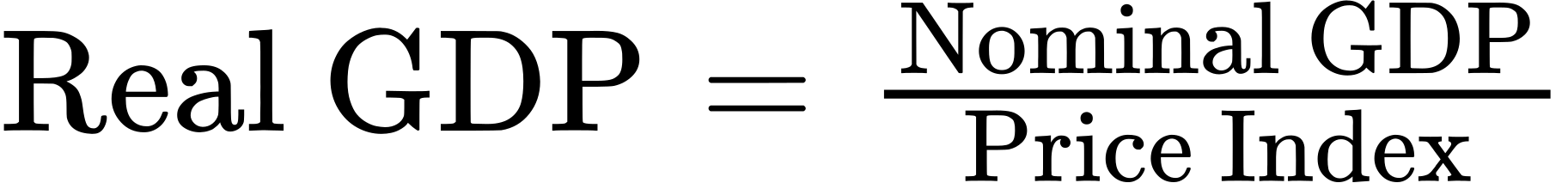

With GDP, it is just a tiny bit more complicated. We start with the same formula as above:

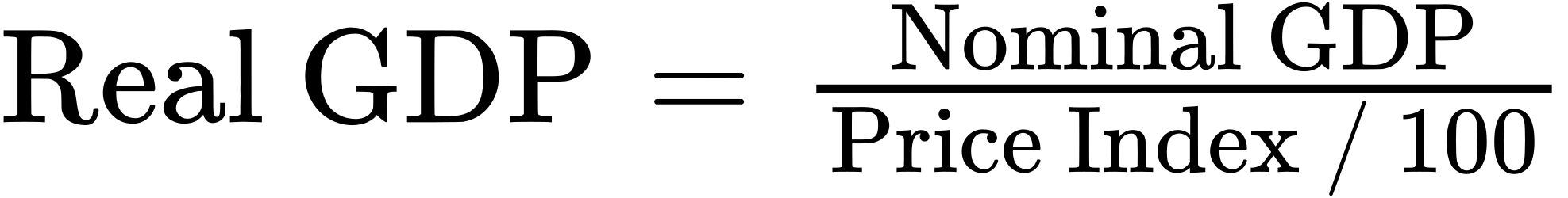

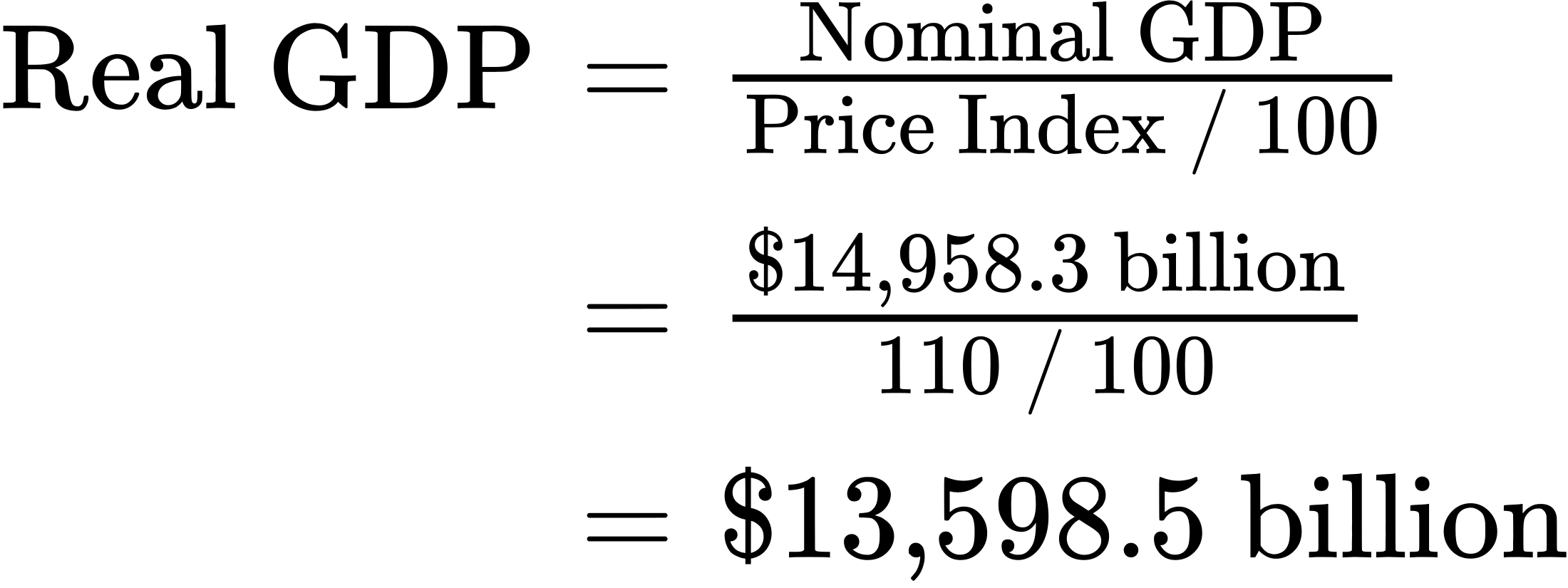

For reasons that we will explain in more detail below, mathematically, a price index is a two-digit decimal number like 1.00 or 0.85 or 1.25. Because some people have trouble working with decimals, when the price index is published, it has traditionally been multiplied by 100 to get integer numbers like 100, 85, or 125. What this means is that when we “deflate” nominal figures to get real figures (by dividing the nominal by the price index). We also need to remember to divide the published price index by 100 to make the math work. Thus, the formula becomes:

Now read the following Work It Out feature for more practice calculating real GDP.

Work It Out

Computing GDP

It is possible to use the data in Table 6.5 to compute real GDP.

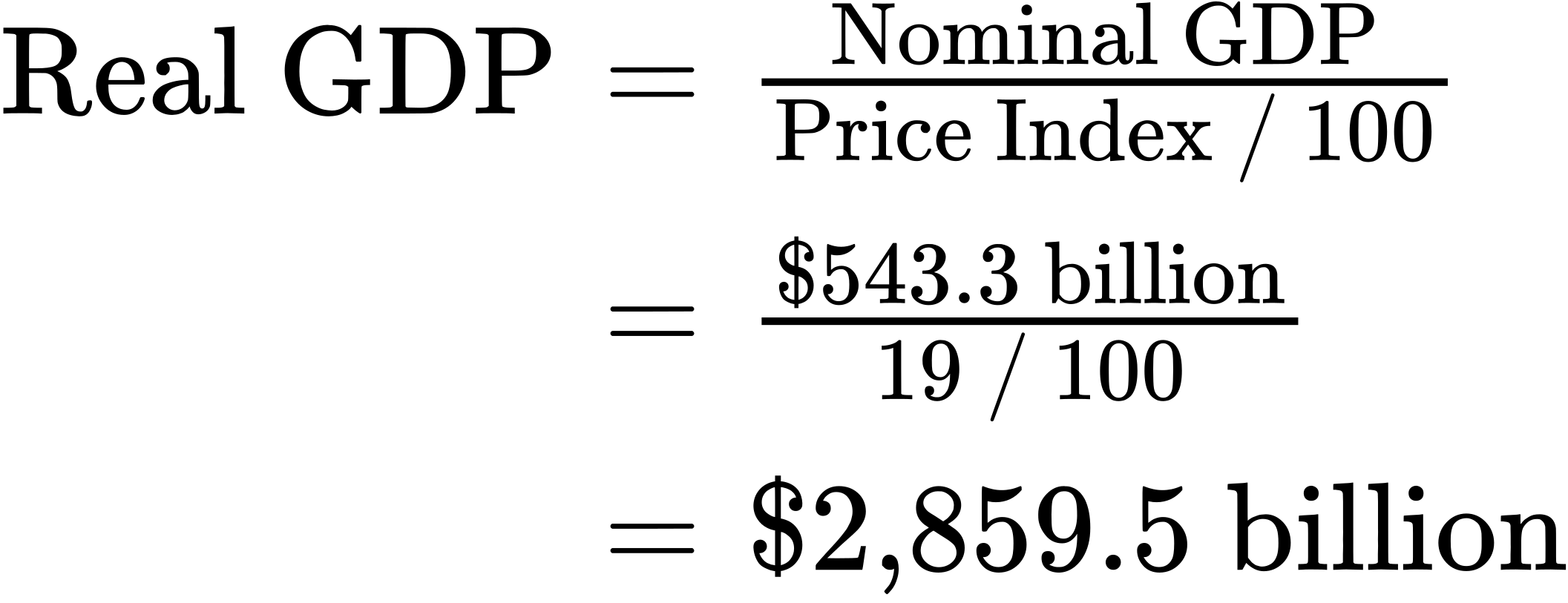

Step 1. Look at Table 6.5, to see that, in 1960, nominal GDP was $543.3 billion and the price index (GDP deflator) was 19.0.

Step 2. To calculate the real GDP in 1960, use the formula:

We’ll do this in two parts to make it clear. First adjust the price index: 19 divided by 100 = 0.19. Then divide into nominal GDP: $543.3 billion / 0.19 = $2,859.5 billion.

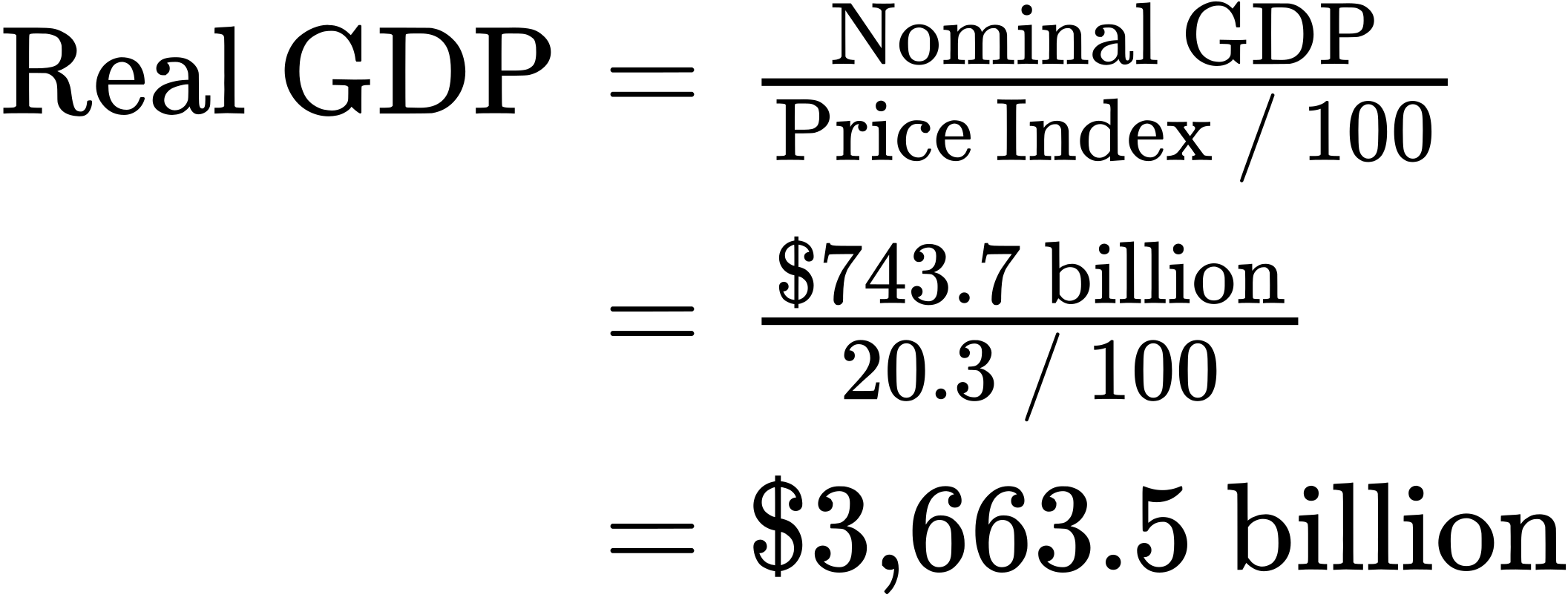

Step 3. Use the same formula to calculate the real GDP in 1965.

Step 4. Continue using this formula to calculate all of the real GDP values from 1960 through 2010. The calculations and the results are in Table 4.4.

|

Year |

Nominal GDP (billions of dollars) |

GDP Deflator (2005 = 100) |

Calculations |

Real GDP (billions of 2005 dollars) |

|

1960 |

543.3 |

19.0 |

543.3 / (19.0/100) |

2859.5 |

|

1965 |

743.7 |

20.3 |

743.7 / (20.3/100) |

3663.5 |

|

1970 |

1075.9 |

24.8 |

1,075.9 / (24.8/100) |

4338.3 |

|

1975 |

1688.9 |

34.1 |

1,688.9 / (34.1/100) |

4952.8 |

|

1980 |

2862.5 |

48.3 |

2,862.5 / (48.3/100) |

5926.5 |

|

1985 |

4346.7 |

62.3 |

4,346.7 / (62.3/100) |

6977.0 |

|

1990 |

5979.6 |

72.7 |

5,979.6 / (72.7/100) |

8225.0 |

|

1995 |

7664.0 |

82.0 |

7,664 / (82.0/100) |

9346.3 |

|

2000 |

10289.7 |

89.0 |

10,289.7 / (89.0/100) |

11561.5 |

|

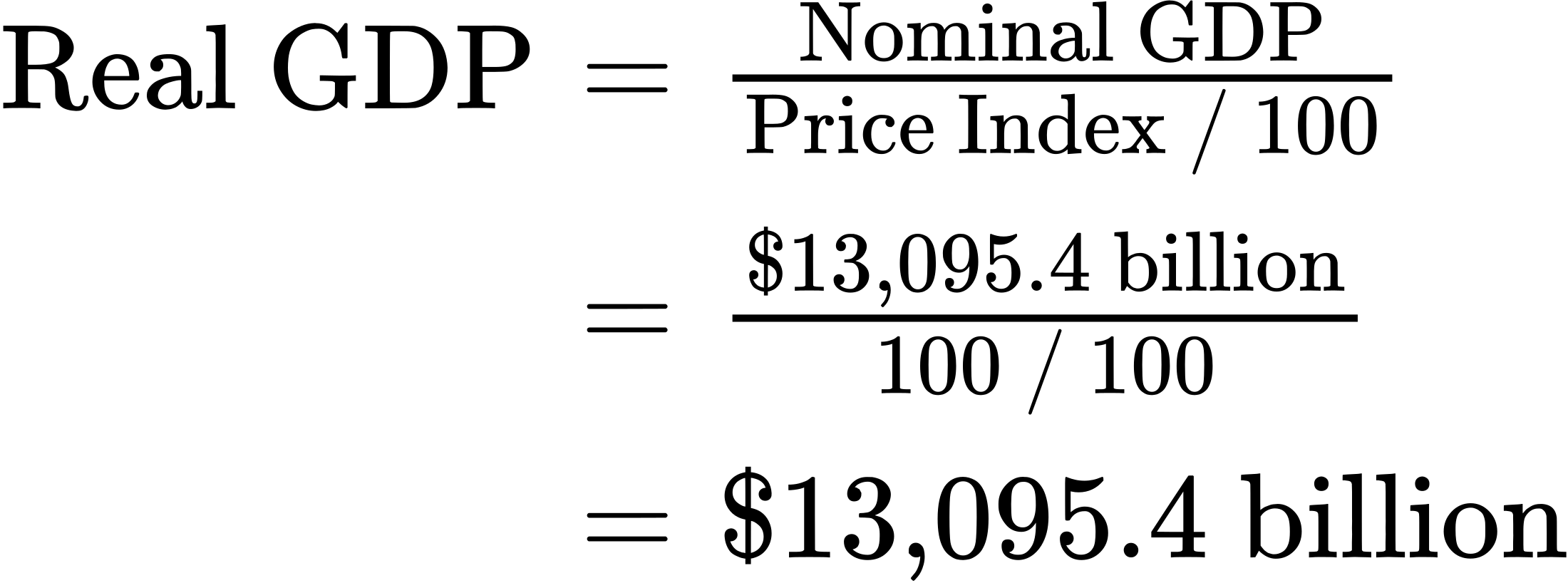

2005 |

13095.4 |

100.0 |

13,095.4 / (100.0/100) |

13095.4 |

|

2010 |

14958.3 |

110.0 |

14,958.3 / (110.0/100) |

13598.5 |

Table 4.4 Converting Nominal to Real GDP (Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, www.bea.gov)

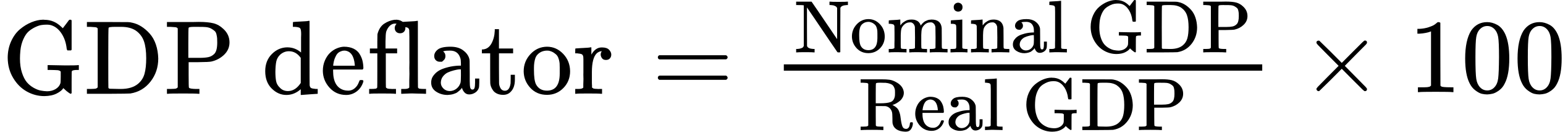

There are a couple things to notice here. Whenever you compute a real statistic, one year (or period) plays a special role. It is called the base year (or base period). The base year is the year whose prices we use to compute the real statistic. When we calculate real GDP, for example, we take the quantities of goods and services produced in each year (for example, 1960 or 1973) and multiply them by their prices in the base year (in this case, 2005), so we get a measure of GDP that uses prices that do not change from year to year. That is why real GDP is labeled “Constant Dollars” or, in this example, “2005 Dollars,” which means that real GDP is constructed using prices that existed in 2005. While the example here uses 2005 as the base year, more generally, you can use any year as the base year. The formula is:

Rearranging the formula and using the data from 2005:

Comparing real GDP and nominal GDP for 2005, you see they are the same. This is no accident. It is because we have chosen 2005 as the “base year” in this example. Since the price index in the base year always has a value of 100 (by definition), nominal and real GDP are always the same in the base year.

Look at the data for 2010.

Use this data to make another observation: As long as inflation is positive, meaning prices increase on average from year to year, real GDP should be less than nominal GDP in any year after the base year. The reason for this should be clear: The value of nominal GDP is “inflated” by inflation. Similarly, as long as inflation is positive, real GDP should be greater than nominal GDP in any year before the base year.

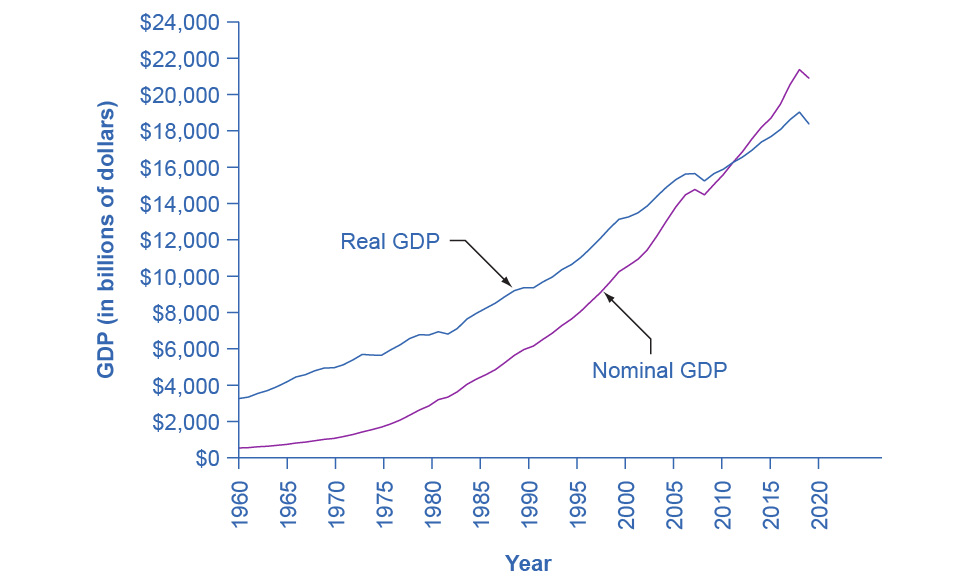

Figure 4.5 shows the U.S. nominal and real GDP since 1960. Because 2005 is the base year, the nominal and real values are exactly the same in that year. However, over time, the rise in nominal GDP looks much larger than the rise in real GDP (that is, the nominal GDP line rises more steeply than the real GDP line), because the presence of inflation, especially in the 1970s exaggerates the rise in nominal GDP.

“U.S. Nominal and Real GDP, 1960–2020, 1960-2020” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 4.5 U.S. Nominal and Real GDP, 1960–2020 The red line measures U.S. GDP in nominal dollars. The blue line measures U.S. GDP in real dollars, where all dollar values are converted to 2012 dollars. Since we express real GDP in 2012 dollars, the two lines cross in 2012. However, real GDP will appear higher than nominal GDP in the years before 2012, because dollars were worth less in 2012 than in previous years. Conversely, real GDP will appear lower in the years after 2012, because dollars were worth more in 2012 than in later years.

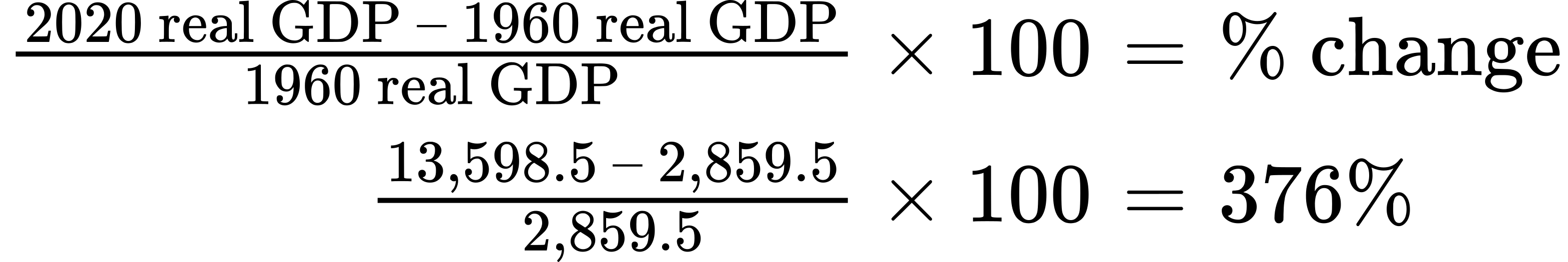

Let’s return to the question that we posed originally: How much did GDP increase in real terms? What was the real GDP growth rate from 1960 to 2012? To find the real growth rate, we apply the formula for percentage change:

In other words, the U.S. economy has increased real production of goods and services by nearly a factor of five since 1960. Of course, that understates the material improvement since it fails to capture improvements in the quality of products and the invention of new products.

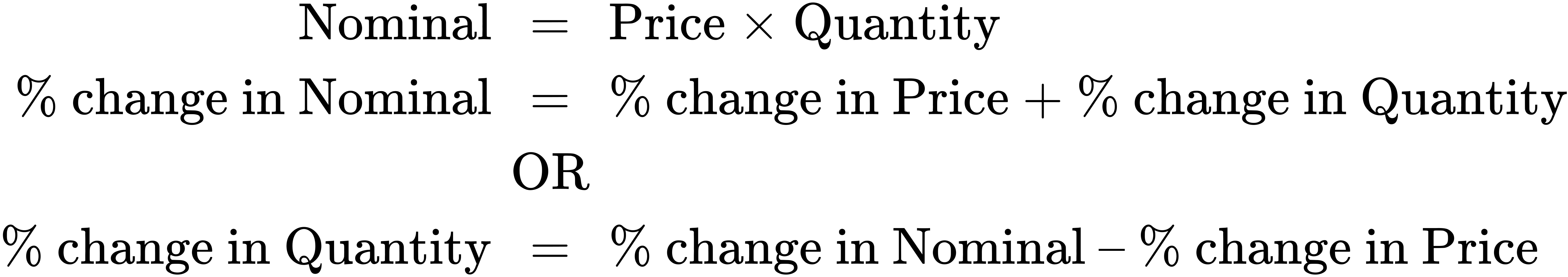

There is a quicker way to answer this question approximately, using another math trick. Because:

Therefore, real GDP growth rate (% change in quantity) equals the growth rate in nominal GDP (% change in value) minus the inflation rate (% change in price).

Note that using this equation provides an approximation for small changes in the levels. For more accurate measures, one should use the first formula.

This chapter is a remixed version of the chapters 6.2 Adjusting Nominal Values to Real Values in Principles of Macroeconomics 3e by OpenStax, published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Other additions and modifications have been made in accord with the style, structure, and audience of this guide.