Chapter 6.4: Unemployment Insurance

6.4 Unemployment Insurance and Classical View of Unemployment

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how unemployment insurance can be used to measure unemployment

- Explain Unemployment using supply demand model

Unemployment Insurance as a Method of Measuring Unemployment

Unemployment Insurance – Unemployment insurance began in the mid-1930s, after the Great Depression, as a possible way for the government to help households and to provide income to get the economy started on a pattern of growth. The idea was to provide a minimum level of income necessary to keep the demand for goods from falling as much as it did in the 30s. It served two purposes. One was to aid the macroeconomy and to prevent another depression and secondly to help individuals make through rough times. Unemployment insurance can increase the duration of unemployment since it provides some income to the unemployed. The pressure to find another job is not as great if there were no insurance.

The first cost associated with unemployment insurance is that it promotes a longer duration of unemployment, and can thereby lowers output, slows economic growth, and lowers living standards. It also diverts taxpayer’s money from funding other government projects such as infrastructure, education, and healthcare. The second cost is that it requires firms and employees to pay into insurance funds, thereby reducing disposable income, which in turn lowers consumption and negatively impacts GDP.

Another way of measuring unemployment is by measuring the amount of people collecting unemployment insurance benefits, a statistic provided on a weekly basis by the BLS. Its main use is on persons filing initial claims for benefits payments when they become unemployed. However, this is not an accurate method of measuring unemployment because many people who are unemployed do not collect unemployment insurance. This is because in order to collect unemployment insurance, a person must: a) lose the job b) previously worked for 6 months c) applied for benefits d) have not exhausted their period, in which they may collect the payment. For example, students after graduation who did not work and cannot find jobs are not eligible for unemployment insurance.

Classical View of Unemployment

Up until the great depression, economists look at the labor market in terms of supply, demand and market equilibrium. The labor market represents a relationship between the price of labor, also known as the wage rate, and the quantity of labor.

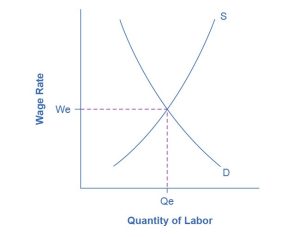

According to the classical view, the markets always tend to be in equilibrium where the quantity demanded of labor by firms equals the quantity supply of labor by households. Check Figure 6.3 for an illustration of this concept.

“The Unemployment and Equilibrium in the Labor Market” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 6.1 The Unemployment and Equilibrium in the Labor Market In a labor market with flexible wages, the equilibrium will occur at wage We and quantity Qe, where the number of people who want jobs (shown by S) equals the number of jobs available (shown by D).

Labor supply curve – amount of labor that households want to supply given a wage rate. The higher the wage rate, the higher the quantity supplied of labor. More people would like to work outside the house. Each household look at the wage rate, the prices of outputs in the market, the value of leisure time, value of staying home and raising children and decide if they want to be part of the labor force. In some societies, if the wage rate is very low, some farmers will decide not to take a job and produce their own food and shelter.

Labor demand curve – a graph that illustrates the amount of labor that firms want to employ at a particular wage rate. The higher the wage rate, the lower the quantity demanded of labor. In other words, the higher the wage rate, firms want to hire less workers. However, as the wage rate declines, firms want to hire more workers. Each firm’s decision is part of its overall profit maximizing decision. Firms make profits by selling output to households. The amount of labor that firms will hire depends on the value of output that workers produce.

Market Equilibrium – In a supply-and-demand model of a labor market, as Figure 6.4 illustrates, the labor market should move toward an equilibrium wage and quantity. At the equilibrium wage (We), the equilibrium quantity (Qe) of labor supplied by workers should be equal to the quantity of labor demanded by employers.

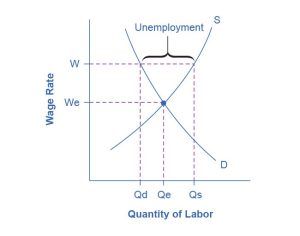

According to classical view there is always equilibrium in the labor market and the economy operates on full employment. If the wages for whatever reason are above equilibrium, (check Figure 8.3) that can cause (short-lived) unemployment. As a result of surplus of workers, wages will tend to go down, causing firms to hire more and households to decrease quantity supply of labor; thus, creating a new equilibrium at a lower wage rate. The assumption is that prices (which include wages) are perfectly flexible.

“Sticky Wages in the Labor Market” by OpenStax, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 6.2: Unemployment in the Labor Market

So how does the classical view explain unemployment?

The fact that there are people willing to work at a wage higher than the current wage does not mean that the labor market is not working.

Explaining Unemployment

Sticky wages – Figure 8.4 – wages being sticky on the downward side, it argues that wages will not adjust to clear the labor market. There are 4 main reasons for wages being above equilibrium:

- Efficiency wage theory – productivity of workers increases with the wage rate. Paying workers more than the market-clearing wage can increase morale and low turnovers. However, at higher wages, more people are looking for work thus creating unemployment.

- Imperfect information – wages may be set wrong, too high for example, because firms may not know what the market-clearing wage in the market is so more people apply for these jobs, the firm can only hire a certain number and as a result: unemployment.

- Minimum wage laws – Price Floor Effect: When the government sets a minimum wage above the equilibrium wage (the wage that would naturally prevail in a competitive labor market), it creates a price floor for labor. Employers are required to pay their workers at least the minimum wage, even if the value of their labor is below that level. Minimum wage causes firms to hire less workers and households to supply more workers – creating unemployment.

- Unions- Unions demand a salary that might be higher than the market equilibrium, creating structural unemployment.

This chapter was written by Professor Karen David and is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This chapter was written by Karen David and published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This chapter also contains graphs from chapter 8.3 What Causes Changes in Unemployment over the Short Run in Principles of Macroeconomics 3e by OpenStax, published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.