1

CHAPTER OUTLINE

1.1 What Is Psychology?

1.2 History of Psychology

1.3 Contemporary Psychology

1.4 Careers in Psychology

INTRODUCTION Clive Wearing is an accomplished musician who lost his ability to form new memories when he became sick at the age of 46. While he can remember how to play the piano perfectly, he cannot remember what he ate for breakfast just an hour ago (Sacks, 2007). James Wannerton experiences a taste sensation that is associated with the sound of words. His former girlfriend’s name tastes like rhubarb (Mundasad, 2013). John Nash is a brilliant mathematician and Nobel Prize winner. However, while he was a professor at MIT, he would tell people that the New York Times contained coded messages from extraterrestrial beings that were intended for him. He also began to hear voices and became suspicious of the people around him. Soon thereafter, Nash was diagnosed with schizophrenia and admitted to a state-run mental institution (O’Connor & Robertson, 2002). Nash was the subject of the 2001 movie A Beautiful Mind. Why did these people have these experiences? How does the human brain work? And what is the connection between the brain’s internal processes and people’s external behaviors? This textbook will introduce you to various ways that the field of psychology has explored these questions.

1.1 What is Psychology?

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define Psychology

- Understand the merits of an education in psychology

Psychology refers to the scientific study of the mind and behavior. Psychologists use the scientific method to acquire knowledge. To apply the scientific method, a researcher with a question about how or why something happens will propose a tentative explanation, called a hypothesis, to explain the phenomenon. A hypothesis should fit into the context of a scientific theory, which is a broad explanation or group of explanations for some aspect of the natural world that is consistently supported by evidence over time. A theory is the best understanding we have of that part of the natural world. The researcher then makes observations or carries out an experiment to test the validity of the hypothesis. Those results are then published or presented at research conferences so that others can replicate or build on the results.

Scientists test that which is perceivable and measurable. For example, the hypothesis that a bird sings because it is happy is not a hypothesis that can be tested since we have no way to measure the happiness of a bird. We must ask a different question, perhaps about the brain state of the bird, since this can be measured. However, we can ask individuals about whether they sing because they are happy since they are able to tell us. Thus, psychological science is empirical, and based on observation, including experimentation, rather than a method based only on forms of logical argument or previous authorities.

It was not until the late 1800s that psychology became accepted as its own academic discipline. Before this time, the workings of the mind were considered under the auspices of philosophy. Given that any behavior is, at its roots, biological, some areas of psychology take on aspects of a natural science like biology. No biological organism exists in isolation, and our behavior is influenced by our interactions with others. Therefore, psychology is also a social science.

WHY STUDY PSYCHOLOGY?

Often, students take their first psychology course because they are interested in helping others and want to learn more about themselves and why they act the way they do. Sometimes, students take a psychology course because it either satisfies a general education requirement or is required for a program of study such as nursing or pre-med. Many of these students develop such an interest in the area that they go on to declare psychology as their major. As a result, psychology is one of the most popular majors on college campuses across the United States (Johnson & Lubin, 2011). A number of well-known individuals were psychology majors. Just a few famous names on this list are Facebook’s creator Mark Zuckerberg, television personality and political satirist Jon Stewart, actress Natalie Portman, and filmmaker Wes Craven (Halonen, 2011). About 6 percent of all bachelor degrees granted in the United States are in the discipline of psychology (U.S. Department of Education, 2016).

An education in psychology is valuable for a number of reasons. Psychology students hone critical thinking skills and are trained in the use of the scientific method. Critical thinking is the active application of a set of skills to information for the understanding and evaluation of that information. The evaluation of information—assessing its reliability and usefulness— is an important skill in a world full of competing “facts,” many of which are designed to be misleading. For example, critical thinking involves maintaining an attitude of skepticism, recognizing internal biases, making use of logical thinking, asking appropriate questions, and making observations. Psychology students also can develop better communication skills during the course of their undergraduate coursework (American Psychological Association, 2011). Together, these factors increase students’ scientific literacy and prepare students to critically evaluate the various sources of information they encounter. [1]

LINK TO LEARNING: Watch a brief video about some questions to consider before deciding to major in psychology to learn more.

1.1 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 1.1 What is Psychology?

Psychology is defined as the scientific study of mind and behavior. Students of psychology develop critical thinking skills, become familiar with the scientific method, and recognize the complexity of behavior.

1.2 History of Psychology

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the influence of philosophy and physiology in the development of psychology as a science.

- Understand the importance of Wundt and James in the development of psychology

- Appreciate Freud’s influence on psychology

- Understand the basic tenets of Gestalt psychology

- Appreciate the important role that behaviorism played in psychology’s history

- Understand basic tenets of humanism

- Understand how the cognitive revolution shifted psychology’s focus back to the mind

Precursors to American psychology can be found in philosophy and physiology. Philosophers such as John Locke (1632–1704) and Thomas Reid (1710–1796) promoted empiricism, the idea that all knowledge comes from experience (Figure 1.2). The work of Locke, Reid, and others emphasized the role of the human observer and the primacy of the senses in defining how the mind comes to acquire knowledge. In American colleges and universities in the early 1800s, these principles were taught as courses on mental and moral philosophy. Most often these courses taught about the mind based on the faculties of intellect, will, and the senses (Fuchs, 2000). [2]

Physiology and Psychophysics

Philosophical questions about the nature of mind and knowledge were matched in the 19th century by physiological investigations of the sensory systems of the human observer. German physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) measured the speed of the neural impulse and explored the physiology of hearing and vision. His work indicated that our senses can deceive us and are not a mirror of the external world. Such work showed that even though the human senses were fallible, the mind could be measured using the methods of science. In all, it suggested that a science of psychology was feasible.

An important implication of Helmholtz’s work was that there is a psychological reality and a physical reality and that the two are not identical. This was not a new idea; philosophers like John Locke had written extensively on the topic, and in the 19th century, philosophical speculation about the nature of mind became subject to the rigors of science.

The question of the relationship between the mental (experiences of the senses) and the material (external reality) was investigated by a number of German researchers including Ernst Weber and Gustav Fechner (Figure 1.4). Their work was called psychophysics, and it introduced methods for measuring the relationship between physical stimuli and human perception that would serve as the basis for the new science of psychology (Fancher & Rutherford, 2011). [3]

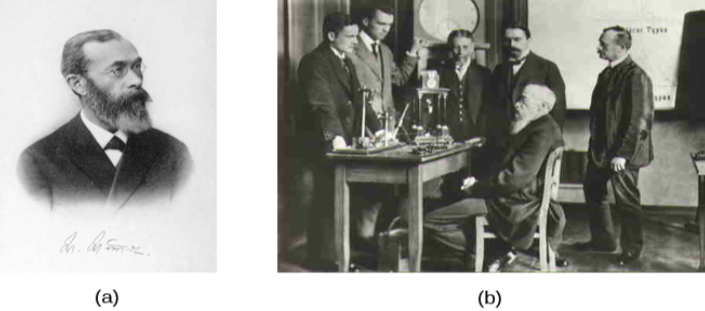

Wilhelm Wundt and The Founding of Psychology

The formal development of modern psychology is usually credited to the work of German physician, physiologist, and philosopher Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920). Wundt helped to establish the field of experimental psychology by serving as a strong promoter of the idea that psychology could be an experimental field and by providing classes, textbooks, and a laboratory for training students. In 1875, he joined the faculty at the University of Leipzig and quickly began to make plans for the creation of a program of experimental psychology. In 1879, he complemented his lectures on experimental psychology with a laboratory experience: an event that has served as the popular date for the establishment of the science of psychology.

The response to the new science was immediate and global. Wundt attracted students from around the world to study the new experimental psychology and work in his lab (Figure 1.5). . Students were trained to offer detailed self-reports of their reactions to various stimuli, a procedure known as introspection. The goal was to objectively identify the elements of consciousness, by viewing the human mind as akin to any aspect of nature that could be observed. In addition to the study of sensation and perception, research was done on mental chronometry, more commonly known as reaction time. The work of Wundt and his students demonstrated that the mind could be measured and the nature of consciousness could be revealed through scientific means. It was an exciting proposition, and one that found great interest in America. After the opening of Wundt’s lab in 1879, it took just four years for the first psychology laboratory to open in the United States (Benjamin, 2007).[4]

Scientific Psychology Comes to the United States

Wundt’s version of psychology arrived in America most visibly through the work of Edward Bradford Titchener (1867–1927) (Figure 1.6). A student of Wundt’s, Titchener brought to America a brand of experimental psychology referred to as “structuralism.” Structuralists were interested in the breaking down of the contents of the mind into its most basic components so that one could understand what the mind is. For Titchener, the general adult mind was the proper focus for the new psychology, and he excluded from study those with mental deficiencies, children, and animals (Evans, 1972; Titchener, 1909 edited by Maria Pagano).

Experimental psychology spread rather rapidly throughout North America. By 1900, there were more than 40 laboratories in the United States and Canada (Benjamin, 2000). Psychology in America also organized early with the establishment of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1892. Titchener felt that this new organization did not adequately represent the interests of experimental psychology, so, in 1904, he organized a group of colleagues to create what is now known as the Society of Experimental Psychologists (Goodwin, 1985). The group met annually to discuss research in experimental psychology. Reflecting the times, women researchers were not invited (or welcome). It is interesting to note that Titchener’s first doctoral student was a woman, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939). Despite many barriers, in 1894, Washburn became the first woman in America to earn a Ph.D. in psychology and, in 1921, only the second woman to be elected president of the American Psychological Association (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987).

Striking a balance between the science and practice of psychology continues to this day. In 1988, the American Psychological Society (now known as the Association for Psychological Science) was founded with the central mission of advancing psychological science.

William James (1842–1910) was the first American psychologist who espoused a different perspective on how psychology should operate (Figure 1.7). James was introduced to Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection and accepted it as an explanation of an organism’s characteristics. Key to that theory is the idea that natural selection leads to organisms that are adapted to their environment, including their behavior. Adaptation means that a trait of an organism has a function for the survival and reproduction of the individual, because it has been naturally selected. As James saw it, psychology’s purpose was to study the function of behavior in the world, and as such, his perspective was known as functionalism. Functionalism focused on how mental activities helped an organism fit into its environment. Functionalism has a second, more subtle meaning in that functionalists were more interested in the operation of the whole mind rather than of its individual parts, which were the focus of structuralism. Like Wundt, James believed that introspection could serve as one means by which someone might study mental activities, but James also relied on more objective measures, including the use of various recording devices, and examinations of concrete products of mental activities and of anatomy and physiology (Gordon, 1995).

Perhaps one of the most influential and well-known figures in psychology’s history was Sigmund Freud (Figure 1.8). Freud (1856–1939) was an Austrian neurologist who was fascinated by patients suffering from “hysteria” and neurosis. Hysteria was an ancient diagnosis for disorders, primarily of women with a wide variety of symptoms, including physical symptoms and emotional disturbances, none of which had an apparent physical cause. Freud theorized that many of his patients’ problems arose from the unconscious mind. In Freud’s view, the unconscious mind was a repository of feelings and urges of which we have no awareness. Gaining access to the unconscious, then, was crucial to the successful resolution of the patient’s problems. According to Freud, the unconscious mind could be accessed through dream analysis, by examinations of the first words that came to people’s minds, and through seemingly innocent slips of the tongue. Psychoanalytic theory focuses on the role of a person’s unconscious, as well as early childhood experiences, and this particular perspective dominated clinical psychology for several decades (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

More modern iterations of Freud’s clinical approach have been empirically demonstrated to be effective (Knekt et al., 2008; Shedler, 2010). Some current practices in psychotherapy involve examining unconscious aspects of the self and relationships, often through the relationship between the therapist and the client. Freud’s historical significance and contributions to clinical practice merit his inclusion in a discussion of the historical movements within psychology.

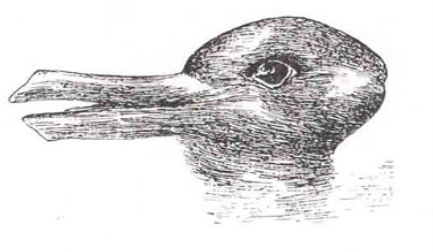

Wertheimer, Koffka, Köhler, and Gestalt Psychology

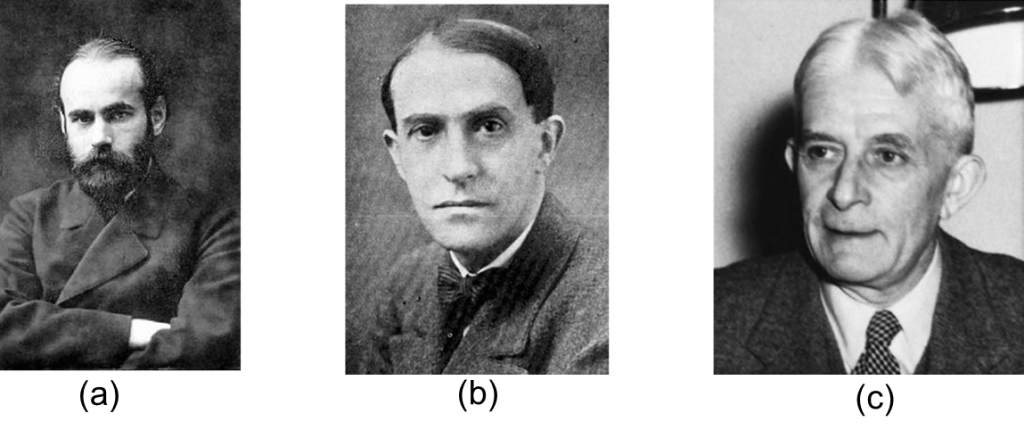

Max Wertheimer (1880–1943), Kurt Koffka (1886–1941), and Wolfgang Köhler (1887–1967) (Figure 1.9)were three German psychologists who immigrated to the United States in the early 20th century to escape Nazi Germany. These scholars are credited with introducing psychologists in the United States to various Gestalt principles. The word Gestalt roughly translates to “whole;” a major emphasis of Gestalt psychology deals with the fact that although a sensory experience can be broken down into individual parts, how those parts relate to each other as a whole is often what the individual responds to in perception. For example, a song may be made up of individual notes played by different instruments, but the real nature of the song is perceived in the combinations of these notes as they form the melody, rhythm, and harmony. In many ways, this particular perspective would have directly contradicted Wundt’s ideas of structuralism (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

Unfortunately, in moving to the United States, these scientists were forced to abandon much of their work and were unable to continue to conduct research on a large scale. These factors along with the rise of behaviorism (described next) in the United States prevented principles of Gestalt psychology from being as influential in the United States as they had been in their native Germany (Thorne & Henley, 2005). Despite these issues, several Gestalt principles are still very influential today. Considering the human individual as a whole rather than as a sum of individually measured parts became an important foundation in humanistic theory late in the century. The ideas of Gestalt have continued to influence research on sensation and perception.

Structuralism, Freud, and the Gestalt psychologists were all concerned in one way or another with describing and understanding inner experience. But other researchers had concerns that inner experience could be a legitimate subject of scientific inquiry and chose instead to exclusively study behavior, the objectively observable outcome of mental processes.

Pavlov, Watson, Skinner, and Behaviorism

Early work in the field of behavior was conducted by the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) (Figure 1.10). Pavlov studied a form of learning behavior called a conditioned reflex, in which an animal or human produced a reflex (unconscious) response to a stimulus and, over time, was conditioned to produce the response to a different stimulus that the experimenter associated with the original stimulus. The reflex Pavlov worked with was salivation in response to the presence of food. The salivation reflex could be elicited using a second stimulus, such as a specific sound, that was presented in association with the initial food stimulus several times. Once the response to the second stimulus was “learned,” the food stimulus could be omitted. Pavlov’s “classical conditioning” is only one form of learning behavior studied by behaviorists.

John B. Watson (1878–1958) was an influential American psychologist whose most famous work occurred during the early 20th century at Johns Hopkins University (Figure 1.11). While Wundt and James were concerned with understanding conscious experience, Watson thought that the study of consciousness was flawed. Because he believed that objective analysis of the mind was impossible, Watson preferred to focus directly on observable behavior and try to bring that behavior under control. Watson was a major proponent of shifting the focus of psychology from the mind to behavior, and this approach of observing and controlling behavior came to be known as behaviorism. A major object of study by behaviorists was learned behavior and its interaction with inborn qualities of the organism. Behaviorism commonly used animals in experiments under the assumption that what was learned using animal models could, to some degree, be applied to human behavior. Indeed, Tolman (1938) stated, “I believe that everything important in psychology (except … such matters as involve society and words) can be investigated in essence through the continued experimental and theoretical analysis of the determiners of rat behavior at a choice-point in a maze.”

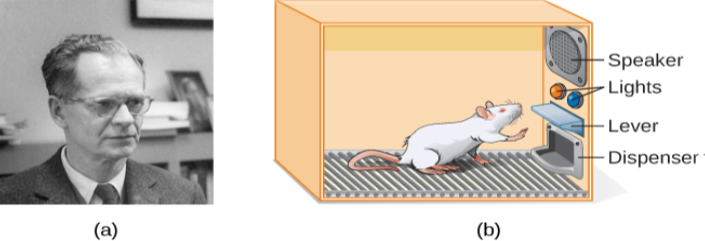

B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) was an American psychologist (Figure 1.12). Like Watson, Skinner was a behaviorist, and he concentrated on how behavior was affected by its consequences. Therefore, Skinner spoke of reinforcement and punishment as major factors in driving behavior. As a part of his research, Skinner developed a chamber that allowed the careful study of the principles of modifying behavior through reinforcement and punishment. This device, known as an operant conditioning chamber (or more familiarly, a Skinner box), has remained a crucial resource for researchers studying behavior (Thorne & Henley, 2005).

Skinner’s focus of learned behaviors had a lasting influence in psychology that has waned somewhat since the growth of research in cognitive psychology. Despite this, conditioned learning is still used in human behavioral modification. Skinner’s two widely read and controversial popular science books about the value of operant conditioning for creating happier lives remain as thought-provoking arguments for his approach (Greengrass, 2004).

Maslow, Rogers, and Humanism

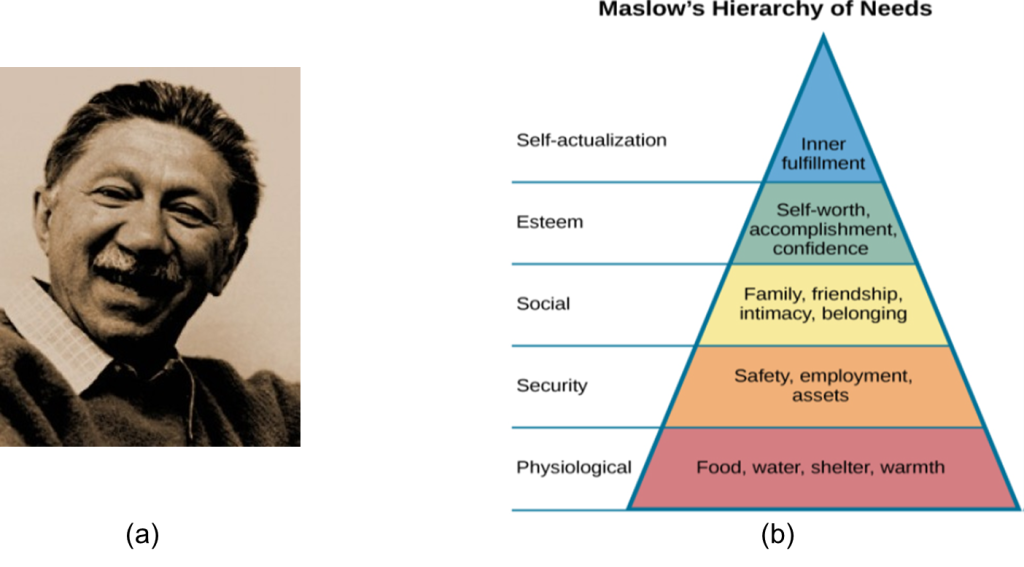

During the early 20th century, American psychology was dominated by behaviorism and psychoanalysis. However, some psychologists were uncomfortable with what they viewed as limited perspectives being so influential to the field. They objected to the pessimism and determinism (all actions driven by the unconscious) of Freud. They also disliked the reductionism, or simplifying nature, of behaviorism. Behaviorism is also deterministic at its core, because it sees human behavior as entirely determined by a combination of genetics and environment. Some psychologists began to form their own ideas that emphasized personal control, intentionality, and a true predisposition for “good” as important for our self-concept and our behavior. Thus, humanism emerged. Humanism is a perspective within psychology that emphasizes the potential for good that is innate to all humans. Two of the most well-known proponents of humanistic psychology are Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers (O’Hara, n.d.).

Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) was an American psychologist who is best known for proposing a hierarchy of human needs in motivating behavior (Figure 1.13). Maslow posited that so long as basic needs necessary for survival were met (e.g., food, water, shelter), higher-level needs (e.g., social needs) would begin to motivate behavior. According to Maslow, the highest-level needs relate to self-actualization, a process by which we achieve our full potential. Obviously, the focus on the positive aspects of human nature that are characteristic of the humanistic perspective is evident (Thorne & Henley, 2005). Humanistic psychologists rejected, on principle, the research approach based on reductionist experimentation in the tradition of the physical and biological sciences, because it missed the “whole” human being. Beginning with Maslow and Rogers, there was an insistence on a humanistic research program. This program has been largely qualitative (not measurement-based), but there exist a number of quantitative research strains within humanistic psychology, including research on happiness, self-concept, meditation, and the outcomes of humanistic psychotherapy (Friedman, 2008).

LINK TO LEARNING: View a brief video of Carl Rogers describing his therapeutic approach to learn more.

The Cognitive Revolution

For decades, behaviorism dominated American psychology. By the 1960s, psychologists began to recognize that behaviorism was unable to fully explain human behavior because it neglected mental processes. The turn toward a cognitive psychology was not new. In the 1930s, British psychologist Frederic C. Bartlett (1886–1969) (Figure 1.15) explored the idea of the constructive mind, recognizing that people use their past experiences to construct frameworks in which to understand new experiences. Some of the major pioneers in American cognitive psychology include Jerome Bruner (1915–2016), and George Miller (1920–2012) (Figure 1.15). [5]

In 1956, Bruner published the book A Study of Thinking, which formally initiated the study of cognitive psychology. Soon afterward Bruner helped found the Harvard Center of Cognitive Studies. After a time, Bruner began to research other topics in psychology, but in 1990 he returned to the subject and gave a series of lectures, later compiled into the book Acts of Meaning. In these lectures, Bruner contested the computer model of the mind, advocating a more holistic understanding of cognitive processes.[6]

Miller’s research on working memory is legendary. His 1956 paper The Magic Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information is one of the most highly cited papers in psychology. A popular interpretation of Miller’s research was that the number of bits of information an average human can hold in working memory is 7 ± 2. Around the same time, the study of computer science was growing and was used as an analogy to explore and understand how the mind works. The work of Miller and others in the 1950s and 1960s has inspired tremendous interest in cognition and neuroscience, both of which dominate much of contemporary American psychology.[7]

(Text from Wikipedia. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 International.). (b) Jerome S. Bruner developed theories on several aspects of cognition, including perception and learning. (c) George A. Miller contributed not only to cognitive psychology but also contributed to the founding of the field of psycholinguistics.

European psychology had never really been as influenced by behaviorism as had American psychology; and thus, the cognitive revolution helped reestablish lines of communication between European psychologists and their American counterparts. Furthermore, psychologists began to cooperate with scientists in other fields, like anthropology, linguistics, computer science, and neuroscience, among others. This interdisciplinary approach often was referred to as the cognitive sciences, and the influence and prominence of this particular perspective resonate in modern-day psychology (Miller, 2003).

Multicultural And Cross-Cultural Psychology

Culture has important impacts on individuals and social psychology, yet the effects of culture on psychology are under-studied. There is a risk that psychological theories and data derived from white, American settings could be assumed to apply to individuals and social groups from other cultures and this is unlikely to be true (Betancourt & López, 1993). One weakness in the field of cross-cultural psychology is that in looking for differences in psychological attributes across cultures, there remains a need to go beyond simple descriptive statistics (Betancourt & López, 1993). In this sense, it has remained a descriptive science, rather than one seeking to determine cause and effect. For example, a study of characteristics of individuals seeking treatment for a binge eating disorder in Hispanic American, African American, and Caucasian American individuals found significant differences between groups (Franko et al., 2012). The study concluded that results from studying any one of the groups could not be extended to the other groups, and yet potential causes of the differences were not measured. Multicultural psychologists develop theories and conduct research with diverse populations, typically within one country. Cross-cultural psychologists compare populations across countries, such as participants from the United States compared to participants from China.

In 1920, Francis Cecil Sumner was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in the United States (Figure 1.16) . Sumner established a psychology degree program at Howard University, leading to the education of a new generation of African American psychologists (Black, Spence, and Omari, 2004). Much of the work of early psychologists from diverse backgrounds was dedicated to challenging intelligence testing and promoting innovative educational methods for children.

Two famous African American researchers and psychologists are Mamie Phipps Clark and her husband, Kenneth Clark (Figure 1.17). They are best known for their studies conducted on African American children and doll preference, research that was instrumental in the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court desegregation case. The Clarks applied their research to social services and opened the first child guidance center in Harlem (American Psychological Association, 2019).

under the digital ID ppmsca.09452. This work has been released into the public domain by its copyright holder, Cowles Communications, Inc.. This applies worldwide.)

Listen to the podcast below describing the Clarks’ research and impact on the Supreme Court decision.

George I. Sanchez contested such testing with Mexican American children (Figure 1.17) . As a psychologist of Mexican heritage, he pointed out that the language and cultural barriers in testing were keeping children from equal opportunities (Guthrie, 1998). By 1940, he was teaching with his doctoral degree at University of Texas at Austin and challenging segregated educational practices (Romo, 1986).

The American Psychological Association has several ethnically based organizations for professional psychologists that facilitate interactions among members. Since psychologists belonging to specific ethnic groups or cultures have the most interest in studying the psychology of their communities, these organizations provide an opportunity for the growth of research on the interplay between culture and psychology.

WOMEN IN PSYCHOLOGY

Although rarely given credit, women have been contributing to psychology since its inception as a field of study (Figure 1.18) . In the mid 1890s, Mary Whiton Calkins completed all requirements toward the PhD in psychology, but Harvard University refused to award her that degree because she was a woman. She had been taught and mentored by William James, who tried and failed to convince Harvard to award her the doctoral degree. Her memory research studied primacy and recency effects (Madigan & O’Hara, 1992), and she also wrote about how structuralism and functionalism both explained self-psychology (Calkins, 1906). In 1894, Margaret Floy Washburn was the first woman awarded the doctoral degree in psychology. She wrote The Animal Mind: A Textbook of Comparative Psychology, and it was the standard in the field for over 20 years. Another influential woman, Mary Cover Jones, conducted a study she considered to be a sequel to John B. Watson’s study of Little Albert (you’ll learn about this study in the chapter on Learning). Jones unconditioned fear in Little Peter, who had been afraid of rabbits (Jones, 1924).

Ethnic minority women contributing to the field of psychology include Martha Bernal and Inez Beverly Prosser; their studies were related to education (Figure 1.19). Bernal, the first Latina to earn her doctoral degree in psychology (1962) conducted much of her research with Mexican American children. Prosser was the first African American woman awarded the PhD in 1933 at the University of Cincinnati (Benjamin, Henry, & McMahon, 2005).

1.2 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 1.2 History of Psychology

Before the time of Wundt and James, questions about the mind were considered by philosophers such as John Locke and Thomas Reid who promoted the idea of empiricism. Questions about the nature of mind and knowledge were matched by 19th century investigations of the sensory systems by physiologists such as Hermann von Helmholtz who measured the speed of the neural impulse. In addition to the work being done by physiologists, there were psychophysicists such as Ernst Weber and Gustav Fechner who studied the relationship between the experiences of the senses and external reality.

Both Wundt and James helped create psychology as a distinct scientific discipline. Wundt was a structuralist, which meant he believed that our cognitive experience was best understood by breaking that experience into its component parts. He thought this was best accomplished by introspection.

William James was the first American psychologist, and he was a proponent of functionalism. This particular perspective focused on how mental activities served as adaptive responses to an organism’s environment. Like Wundt, James also relied on introspection; however, his research approach also incorporated more objective measures as well.

Sigmund Freud believed that understanding the unconscious mind was absolutely critical to understand conscious behavior. This was especially true for individuals that he saw who suffered from various hysterias and neuroses. Freud relied on dream analysis, slips of the tongue, and free association as means to access the unconscious. Psychoanalytic theory remained a dominant force in clinical psychology for several decades.

Gestalt psychology was very influential in Europe. Gestalt psychology takes a holistic view of an individual and his experiences. As the Nazis came to power in Germany, Wertheimer, Koffka, and Köhler immigrated to the United States. Although they left their laboratories and their research behind, they did introduce America to Gestalt ideas. Some of the principles of Gestalt psychology are still very influential in the study of sensation and perception.

One of the most influential schools of thought within psychology’s history was behaviorism. Behaviorism focused on making psychology an objective science by studying overt behavior and deemphasizing the importance of unobservable mental processes. John Watson is often considered the father of behaviorism, and B. F. Skinner’s contributions to our understanding of principles of operant conditioning cannot be underestimated.

As behaviorism and psychoanalytic theory took hold of so many aspects of psychology, some began to become dissatisfied with psychology’s picture of human nature. Thus, a humanistic movement within psychology began to take hold. Humanism focuses on the potential of all people for good. Both Maslow and Rogers were influential in shaping humanistic psychology.

During the 1950s, the landscape of psychology began to change. A science of behavior began to shift back to its roots of focus on mental processes. The emergence of neuroscience and computer science aided this transition. Ultimately, the cognitive revolution took hold, and people came to realize that cognition was crucial to a true appreciation and understanding of behavior.

1.3 Contemporary Psychology

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Appreciate the diversity of interests and foci within psychology

- Understand basic interests and applications in each of the described areas of psychology

- Demonstrate familiarity with some of the major concepts or important figures in each of the described areas of psychology

Contemporary psychology is a diverse field that is influenced by all of the historical perspectives described in the preceding section. Reflective of the discipline’s diversity is the diversity seen within the American Psychological Association (APA). The APA is the largest professional organization of psychologists in the world, and its mission is to advance and disseminate psychological knowledge for the betterment of people. There are 56 divisions within the APA, representing a wide variety of specialties that range from Societies for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality to Exercise and Sport Psychology to Behavioral Neuroscience and Comparative Psychology. Reflecting the diversity of the field of psychology itself, members, affiliate members, and associate members span the spectrum from students to doctoral-level psychologists and come from a variety of places including educational settings, criminal justice, hospitals, the armed forces, and industry (American Psychological Association, 2014).

The Association for Psychological Science (APS) was founded in 1988 and seeks to advance the scientific orientation of psychology. Its founding resulted from disagreements between members of the scientific and clinical branches of psychology within the APA. The APS publishes five research journals and engages in education and advocacy with funding agencies. A significant proportion of its members are international, although the majority is located in the United States. Other organizations provide networking and collaboration opportunities for professionals of several ethnic or racial groups working in psychology, such as the National Latina/o Psychological Association (NLPA), the Asian American Psychological Association (AAPA), the Association of Black Psychologists (ABPsi), and the Society of Indian Psychologists (SIP). Most of these groups are also dedicated to studying psychological and social issues within their specific communities.

This section which follows provides an overview of the major subdivisions within psychology today, and in the order in which they are introduced throughout the remainder of this textbook. This is not meant to be an exhaustive listing, but it will provide insight into the major areas of research and practice of modern-day psychologists.

LINK TO LEARNING: Please visit this website about the divisions within the APA to learn more. View these student resources also provided by the APA.

Biopsychology and Evolutionary Psychology

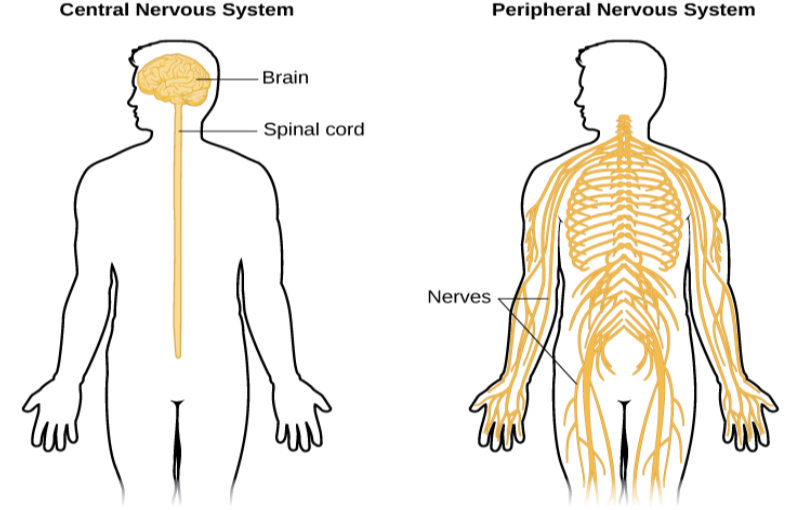

As the name suggests, biopsychology explores how our biology influences our behavior. While biological psychology is a broad field, many biological psychologists want to understand how the structure and function of the nervous system is related to behavior (Figure 1.20). As such, they often combine the research strategies of both psychologists and physiologists to accomplish this goal (as discussed in Carlson, 2013).

While biopsychology typically focuses on the immediate causes of behavior based in the physiology of a human or other animal, evolutionary psychology seeks to study the ultimate biological causes of behavior. To the extent that a behavior is impacted by genetics, a behavior, like any anatomical characteristic of a human or animal, will demonstrate adaption to its surroundings. These surroundings include the physical environment and since interactions between organisms can be important to survival and reproduction, the social environment. The study of behavior in the context of evolution has its origins with Charles Darwin, the co-discoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Darwin was well aware that behaviors should be adaptive and wrote books titled, The Descent of Man (1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), to explore this field.

Evolutionary psychology, and specifically, the evolutionary psychology of humans, has enjoyed a resurgence in recent decades. To be subject to evolution by natural selection, a behavior must have a significant genetic cause. In general, we expect all human cultures to express a behavior if it is caused genetically, since the genetic differences among human groups are small. The approach taken by most evolutionary psychologists is to predict the outcome of a behavior in a particular situation based on evolutionary theory and then to make observations, or conduct experiments, to determine whether the results match the theory.

One drawback of evolutionary psychology is that the traits that we possess now evolved under environmental and social conditions far back in human history, and we have a poor understanding of what these conditions were. This makes predictions about what is adaptive for a behavior difficult. Behavioral traits need not be adaptive under current conditions, only under the conditions of the past when they evolved, about which we can only hypothesize.

Evolutionary psychologists have had success in finding experimental correspondence between observations and expectations. In one example, in a study of mate preference differences between men and women that spanned 37 cultures, Buss (1989) found that women valued earning potential factors greater than men, and men valued potential reproductive factors (youth and attractiveness) greater than women in their prospective mates. In general, the predictions were in line with the predictions of evolution, although there were deviations in some cultures.

Sensation and Perception

Scientists interested in both physiological aspects of sensory systems as well as in the psychological experience of sensory information work within the area of sensation and perception (Figure 1.21). As such, sensation and perception research is also quite interdisciplinary. Imagine walking between buildings as you move from one class to another. You are inundated with sights, sounds, touch sensations, and smells. You also experience the temperature of the air around you and maintain your balance as you make your way. These are all factors of interest to someone working in the domain of sensation and perception.

Cognitive Psychology

As mentioned in the previous section, the cognitive revolution created an impetus for psychologists to focus their attention on better understanding the mind and mental processes that underlie behavior. Thus, cognitive psychology is the area of psychology that focuses on studying cognitions, or thoughts, and their relationship to our experiences and our actions. Like biological psychology, cognitive psychology is broad in its scope and often involves collaborations among people from a diverse range of disciplinary backgrounds. This has led some to coin the term cognitive science to describe the interdisciplinary nature of this area of research (Miller, 2003).

Cognitive psychologists have research interests that span a spectrum of topics, ranging from attention to problem solving to language to memory. The approaches used in studying these topics are equally diverse. Given such diversity, cognitive psychology is not captured in one chapter of this text per se; rather, various concepts related to cognitive psychology will be covered in relevant portions of the chapters in this text on sensation and perception, thinking and intelligence, memory, lifespan development, social psychology, and therapy.

Developmental Psychology

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of development across a lifespan. Developmental psychologists are interested in processes related to physical maturation. However, their focus is not limited to the physical changes associated with aging, as they also focus on changes in cognitive skills, moral reasoning, social behavior, and other psychological attributes.

Early developmental psychologists focused primarily on changes that occurred through reaching adulthood, providing enormous insight into the differences in physical, cognitive, and social capacities that exist between very young children and adults. For instance, research by Jean Piaget (Figure 1.22) demonstrated that very young children do not demonstrate object permanence. Object permanence refers to the understanding that physical things continue to exist, even if they are hidden from us. If you were to show an adult a toy, and then hide it behind a curtain, the adult knows that the toy still exists. However, very young infants act as if a hidden object no longer exists. The age at which object permanence is achieved is somewhat controversial (Munakata, McClelland, Johnson, and Siegler, 1997).

Personality Psychology

Personality psychology focuses on patterns of thoughts and behaviors that make each individual unique. Several individuals (e.g., Freud and Maslow) that we have already discussed in our historical overview of psychology, and the American psychologist Gordon Allport, contributed to early theories of personality. These early theorists attempted to explain how an individual’s personality develops from his or her given perspective. For example, Freud proposed that personality arose as conflicts between the conscious and unconscious parts of the mind were carried out over the lifespan. (Person, 1980).

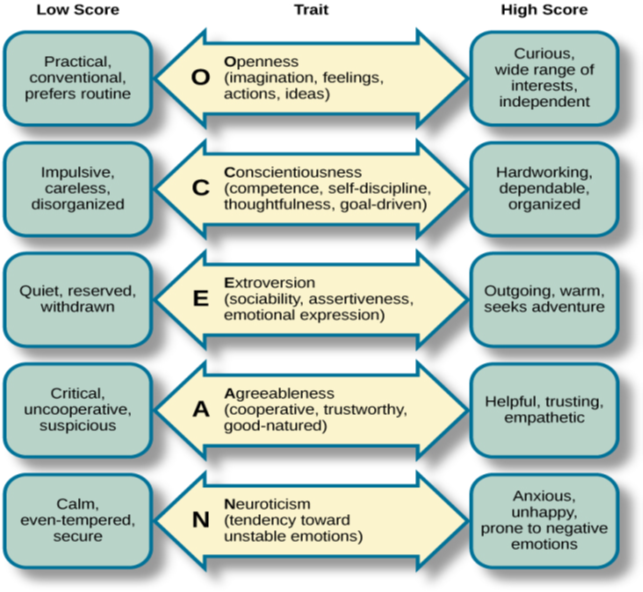

More recently, the study of personality has taken on a more quantitative approach. Rather than explaining how personality arises, research is focused on identifying personality traits, measuring these traits, and determining how these traits interact in a particular context to determine how a person will behave in any given situation. Personality traits are relatively consistent patterns of thought and behavior, and many have proposed that five trait dimensions are sufficient to capture the variations in personality seen across individuals. These five dimensions are known as the “Big Five” or the Five Factor model, and include dimensions of conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion (Figure 1.23). Each of these traits has been demonstrated to be relatively stable over the lifespan (e.g., Rantanen, Metsäpelto, Feldt, Pulkinnen, and Kokko, 2007; Soldz & Vaillant, 1999; McCrae & Costa, 2008) and is influenced by genetics (e.g., Jang, Livesly, and Vernon, 1996).

Social psychology focuses on how we interact with and relate to others. Social psychologists conduct research on a wide variety of topics that include differences in how we explain our own behavior versus how we explain the behaviors of others, prejudice, and attraction, and how we resolve interpersonal conflicts. Social psychologists have also sought to determine how being among other people changes our own behavior and patterns of thinking.

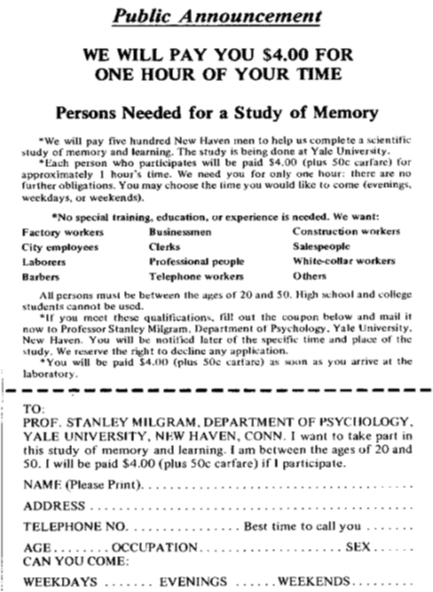

There are many interesting examples of social psychological research, and you will read about many of these in a later chapter of this textbook. Until then, you will be introduced to one of the most controversial psychological studies ever conducted. Stanley Milgram was an American social psychologist who is most famous for research that he conducted on obedience. After the holocaust, in 1961, a Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, who was accused of committing mass atrocities, was put on trial. Many people wondered how German soldiers were capable of torturing prisoners in concentration camps, and they were unsatisfied with the excuses given by soldiers that they were simply following orders. At the time, most psychologists agreed that few people would be willing to inflict such extraordinary pain and suffering, simply because they were obeying orders. Milgram decided to conduct research to determine whether or not this was true (Figure 1.24). As you will read later in the text, Milgram found that nearly two-thirds of his participants were willing to deliver what they believed to be lethal shocks to another person, simply because they were instructed to do so by an authority figure (in this case, a man dressed in a lab coat). This was in spite of the fact that participants received payment for simply showing up for the research study and could have chosen not to inflict pain or more serious consequences on another person by withdrawing from the study. No one was actually hurt or harmed in any way, Milgram’s experiment was a clever ruse that took advantage of research confederates, those who pretend to be participants in a research study who are actually working for the researcher and have clear, specific directions on how to behave during the research study (Hock, 2009). Milgram’s and others’ studies that involved deception and potential emotional harm to study participants catalyzed the development of ethical guidelines for conducting psychological research that discourage the use of deception of research subjects, unless it can be argued not to cause harm and, in general, requiring informed consent of participants.

Industrial-Organizational psychology (I-O psychology) is a subfield of psychology that applies psychological theories, principles, and research findings in industrial and organizational settings. I-O psychologists are often involved in issues related to personnel management, organizational structure, and workplace environment. Businesses often seek the aid of I-O psychologists to make the best hiring decisions as well as to create an environment that results in high levels of employee productivity and efficiency. In addition to its applied nature, I-O psychology also involves conducting scientific research on behavior within I-O settings (Riggio, 2013).

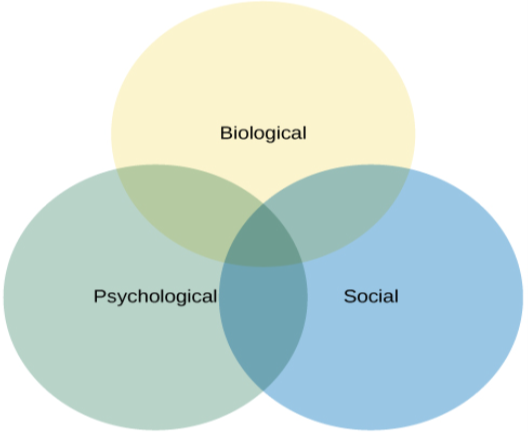

Health Psychology

Health psychology focuses on how health is affected by the interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors. This particular approach is known as the biopsychosocial model (Figure 1.25). Health psychologists are interested in helping individuals achieve better health through public policy, education, intervention, and research. Health psychologists might conduct research that explores the relationship between one’s genetic makeup, patterns of behavior, relationships, psychological stress, and health. They may research effective ways to motivate people to address patterns of behavior that contribute to poorer health (MacDonald, 2013).

Researchers in sport and exercise psychology study the psychological aspects of sport performance, including motivation and performance anxiety, and the effects of sport on mental and emotional wellbeing. Research is also conducted on similar topics as they relate to physical exercise in general. The discipline also includes topics that are broader than sport and exercise but that are related to interactions between mental and physical performance under demanding conditions, such as fire fighting, military operations, artistic performance, and surgery.

Clinical Psychology

Clinical psychology is the area of psychology that focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and other problematic patterns of behavior. As such, it is generally considered to be a more applied area within psychology; however, some clinicians are also actively engaged in scientific research. Counseling psychology is a similar discipline that focuses on emotional, social, vocational, and health-related outcomes in individuals who are considered psychologically healthy.

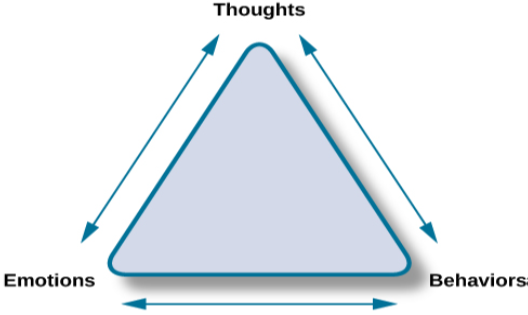

As mentioned earlier, both Freud and Rogers provided perspectives that have been influential in shaping how clinicians interact with people seeking psychotherapy. While aspects of the psychoanalytic theory are still found among some of today’s therapists who are trained from a psychodynamic perspective, Roger’s ideas about client-centered therapy have been especially influential in shaping how many clinicians operate. Furthermore, both behaviorism and the cognitive revolution have shaped clinical practice in the forms of behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (Figure 1.26). Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and problematic patterns of behavior will be discussed in detail in later chapters of this textbook.

Forensic Psychology

Forensic psychology is a branch of psychology that deals questions of psychology as they arise in the context of the justice system. For example, forensic psychologists (and forensic psychiatrists) will assess a person’s competency to stand trial, assess the state of mind of a defendant, act as consultants on child custody cases, consult on sentencing and treatment recommendations, and advise on issues such as eyewitness testimony and children’s testimony (American Board of Forensic Psychology, 2014). In these capacities, they will typically act as expert witnesses, called by either side in a court case to provide their research- or experience-based opinions. As expert witnesses, forensic psychologists must have a good understanding of the law and provide information in the context of the legal system rather than just within the realm of psychology. Forensic psychologists are also used in the jury selection process and witness preparation. They may also be involved in providing psychological treatment within the criminal justice system. Criminal profilers are a relatively small proportion of psychologists that act as consultants to law enforcement.

1.3 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 1.3 Contemporary Psychology

Psychology is a diverse discipline that is made up of several major subdivisions with unique perspectives. Biological psychology involves the study of the biological bases of behavior. Sensation and perception refer to the area of psychology that is focused on how information from our sensory modalities is received, and how this information is transformed into our perceptual experiences of the world around us. Cognitive psychology is concerned with the relationship that exists between thought and behavior, and developmental psychologists study the physical and cognitive changes that occur throughout one’s lifespan. Personality psychology focuses on individuals’ unique patterns of behavior, thought, and emotion. Industrial and organizational psychology,

health psychology, sport and exercise psychology, forensic psychology, and clinical psychology are all considered applied areas of psychology. Industrial and organizational psychologists apply psychological concepts to I-O settings. Health psychologists look for ways to help people live healthier lives, and clinical psychology involves the diagnosis and treatment of psychological disorders and other problematic behavioral patterns. Sport and exercise psychologists study the interactions between thoughts, emotions, and physical performance in sports, exercise, and other activities. Forensic psychologists carry out activities related to psychology in association with the justice system.

1.4 Careers in Psychology

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand educational requirements for careers in academic settings

- Understand the demands of a career in an academic setting

- Understand career options outside of academic settings

Psychologists can work in many different places doing many different things. In general, anyone wishing to continue a career in psychology at a 4-year institution of higher education will have to earn a doctoral degree in psychology for some specialties and at least a master’s degree for others. In most areas of psychology, this means earning a PhD in a relevant area of psychology. Literally, PhD refers to a doctor of philosophy degree, but here, philosophy does not refer to the field of philosophy per se. Rather, philosophy in this context refers to many different disciplinary perspectives that would be housed in a traditional college of liberal arts and sciences.

The requirements to earn a PhD vary from country to country and even from school to school, but usually, individuals earning this degree must complete a dissertation. A dissertation is essentially a long research paper or bundled published articles describing research that was conducted as a part of the candidate’s doctoral training. In the United States, a dissertation generally has to be defended before a committee of expert reviewers before the degree is conferred (Figure 1.27).

Some people earning PhDs may enjoy research in an academic setting. However, they may not be interested in teaching. These individuals might take on faculty positions that are exclusively devoted to conducting research. This type of position would be more likely an option at large, research-focused universities.

In some areas in psychology, it is common for individuals who have recently earned their PhD to seek out positions in postdoctoral training programs that are available before going on to serve as faculty. In most cases, young scientists will complete one or two postdoctoral programs before applying for a full-time faculty position. Postdoctoral training programs allow young scientists to further develop their research programs and broaden their research skills under the supervision of other professionals in the field.

Individuals who wish to become practicing clinical psychologists have another option for earning a doctoral degree, which is known as a PsyD. A PsyD is a doctor of psychology degree that is increasingly popular among individuals interested in pursuing careers in clinical psychology. PsyD programs generally place less emphasis on research-oriented skills and focus more on application of psychological principles in the clinical context (Norcorss & Castle, 2002).

Regardless of whether earning a PhD or PsyD, in most states, an individual wishing to practice as a licensed clinical or counseling psychologist may complete postdoctoral work under the supervision of a licensed psychologist. Within the last few years, however, several states have begun to remove this requirement, which would allow people to get an earlier start in their careers (Munsey, 2009). After an individual has met the state requirements, their credentials are evaluated to determine whether they can sit for the licensure exam. Only individuals that pass this exam can call themselves licensed clinical or counseling psychologists (Norcross, n.d.). Licensed clinical or counseling psychologists can then work in a number of settings, ranging from private clinical practice to hospital settings. It should be noted that clinical psychologists and psychiatrists do different things and receive different types of education. While both can conduct therapy and counseling, clinical psychologists have a PhD or a PsyD, whereas psychiatrists have a doctor of medicine degree (MD). As such, licensed clinical psychologists can administer and interpret psychological tests, while psychiatrists can prescribe medications.

Individuals earning a PhD can work in a variety of settings, depending on their areas of specialization. For example, someone trained as a biopsychologist might work in a pharmaceutical company to help test the efficacy of a new drug. Someone with a clinical background might become a forensic psychologist and work within the legal system to make recommendations during criminal trials and parole hearings, or serve as an expert in a court case.

While earning a doctoral degree in psychology is a lengthy process, usually taking between 5–6 years of graduate study (DeAngelis, 2010), there are a number of careers that can be attained with a master’s degree in psychology. People who wish to provide psychotherapy can become licensed to serve as various types of professional counselors (Hoffman, 2012). Relevant master’s degrees are also sufficient for individuals seeking careers as school psychologists (National Association of School Psychologists, n.d.), in some capacities related to sport psychology (American Psychological Association, 2014), or as consultants in various industrial settings (Landers, 2011, June 14). Undergraduate coursework in psychology may be applicable to other careers such as psychiatric social work or psychiatric nursing, where assessments and therapy may be a part of the job.

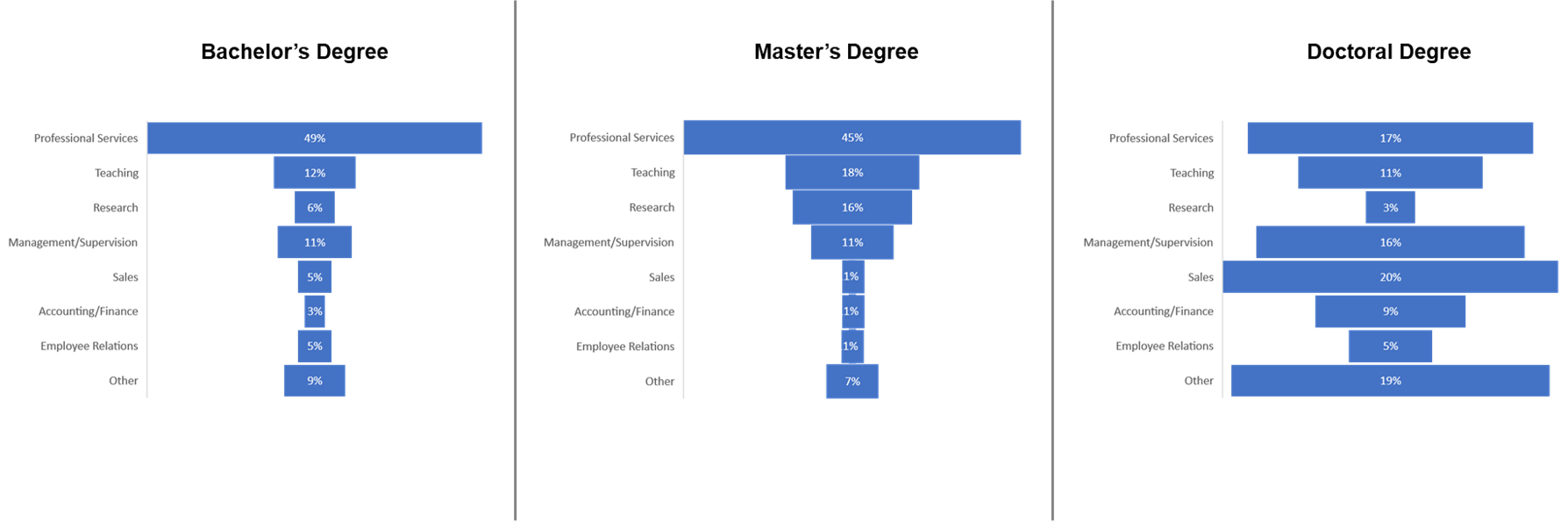

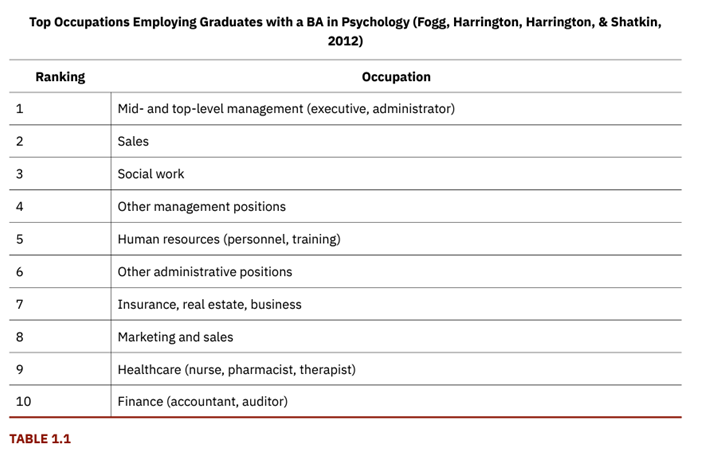

As mentioned in the opening section of this chapter, an undergraduate education in psychology is associated with a knowledge base and skill set that many employers find quite attractive. It should come as no surprise, then, that individuals earning bachelor’s degrees in psychology find themselves in a number of different careers, as shown in the bar chart in Figure 1.28 and in Table 1.1. Examples of a few such careers can involve serving as case managers, working in sales, working in human resource departments, and teaching in high schools. The rapidly growing realm of healthcare professions is another field in which an education in psychology is helpful and sometimes required. For example, the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) exam that people must take to be admitted to medical school now includes a section on the psychological foundations of behavior.

Area of Employment by Level of Psychology Degree Earned[8]

1.4 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 1.4 Careers in Psychology

Generally, academic careers in psychology require doctoral degrees. However, there are a number of nonacademic career options for people who have master’s degrees in psychology. While people with bachelor’s degrees in psychology have more limited psychology-related career options, the skills acquired as a function of an undergraduate education in psychology are useful in a variety of work contexts.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Why do you think psychology courses like this one are often requirements of so many different programs of study?

- Why do you think many people might be skeptical about psychology being a science?

- How did the object of study in psychology change over the history of the field since the 19th century?

- In part, what aspect of psychology was the behaviorist approach to psychology a reaction to?

- Given the incredible diversity among the various areas of psychology that were described in this section, how do they all fit together?

- What are the potential ethical concerns associated with Milgram’s research on obedience?

- Why is an undergraduate education in psychology so helpful in a number of different lines of work?

- Other than a potentially greater salary, what would be the reasons an individual would continue on to get a graduate degree in psychology?

Personal Application Questions

- Why are you taking this course? What do you hope to learn about during this course?

- Freud is probably one of the most well-known historical figures in psychology. Where have you encountered references to Freud or his ideas about the role that the unconscious mind plays in

determining conscious behavior? - Now that you’ve been briefly introduced to some of the major areas within psychology, which are you most interested in learning more about? Why?

- Which of the career options in the field of psychology is most appealing to you?

Tips for How to Remember Theorists and Theories in Psychology

This chapter contains lots of different theorists and theories to remember and when studying for an exam this might become overwhelming for some. One way to better remember all the names and theories for this chapter is to create a mnemonic device. A mnemonic device is a memory aid or technique used to help remember information more easily. It often involves associating complex information with something simpler, such as a word, phrase, or image. Mnemonics work by creating a mental shortcut to recall larger amounts of information. For example, to help you remember B.F Skinner with operant conditioning you can use the mnemonic, “Skinner’s System of Stimulus and Response,” or to help you remember Bandura and modeling you can use the mnemonic, “Bandura Believes in Behavioral Imitation”.

If you can’t think of a mnemonic device on your own, here’s where AI might come in handy. For example, when using AI for assistance with coming up with a mnemonic device to help remember John Locke and nurture I was given the following:

To remember John Locke and the concept of nurture, you could use the mnemonic:

“Locke’s Nurturing Garden”

-

- “Locke” refers to John Locke, the philosopher.

- “Nurturing” connects to his belief in nurture, which emphasized the importance of environment and experience in shaping individuals.

- “Garden” symbolizes growth and development, reinforcing Locke’s idea that people are shaped by their environment, much like how a garden grows based on how it is nurtured.

By visualizing John Locke as a gardener tending to a garden, you can remember that Locke’s ideas focus on nurture — the belief that people’s characteristics are shaped by their experiences, not just their nature.

While mnemonic devices can be helpful for remembering information, they should not replace regular studying. In order for mnemonic device to work well, it needs to be combined with an understanding and review of the material. Please keep in mind that mnemonic devices should be used as a supplement to reinforce what you’ve learned, and not as a shortcut to avoid studying.

Study Guide Outline: Introduction to Psychology Chapter 1.

(Note: Any of the information below can be placed on flash cards or used to create a flowchart or a concept map.)

1. What is Psychology?

A. Definition

-

-

- Psychology: The scientific study of the mind and behavior.

- Psychologists use the scientific method to investigate questions about behavior and mental processes.

- Psychology focuses on what is perceivable and measurable. It’s empirical—based on observation and evidence, not just logic or authority.

-

B. Scientific Method in Psychology

-

-

- Ask a question based on observation.

- Propose a hypothesis – a tentative explanation.

- The hypothesis should align with a scientific theory (a well-supported explanation).

- Test the hypothesis through observation or experiments.

- Publish findings for replication and further research.

-

C. Psychology as a Science

-

-

- Originally part of philosophy, psychology became an official academic discipline in the late 1800s.

- Psychology overlaps with:

- Biological sciences (behavior has biological roots).

- Social sciences (behavior is influenced by interactions with others).

-

D. Why Study Psychology?

-

-

- Personal Interest: Understanding oneself and others.

- Career Relevance: Psychology is useful for fields like nursing, pre-med, education, and business.

- Popular Major: Psychology is one of the most chosen majors in the U.S.

-

E. Skills Gained in Psychology

-

-

- Critical Thinking:

- Skepticism

- Recognizing bias

- Logical analysis

- Asking good questions

- making careful observations

- Scientific Literacy: Understanding and evaluating scientific information.

- Communication Skills: Effectively sharing and discussing ideas and findings.

- Critical Thinking:

-

2. History of Psychology

A. Philosophical and Physiological Foundations

-

-

- Empiricism (Locke & Reid): Knowledge comes from experience and the senses.

- Hermann von Helmholtz: Measured neural impulses and studied vision & hearing. Showed that senses can deceive, but mental processes are measurable.

- Psychophysics (Weber & Fechner): Studied the relationship between physical stimuli and human perception—the basis for experimental psychology.

-

B. Wilhelm Wundt and Structuralism

-

-

- Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920): Founded the first psychology lab in 1879 in Leipzig, Germany. Considered the “father of experimental psychology.”

- Used introspection: self-reporting of experiences to study consciousness.

- Edward Titchener (student of Wundt): Brought structuralism to the U.S.

- Focused on analyzing the mind’s basic components.

- Excluded children, animals, and people with mental disabilities from research.

- Founded the Society of Experimental Psychologists in 1904.

-

C. William James and Functionalism

-

-

- William James (1842–1910): First major American psychologist.

- Influenced by Darwin’s theory of evolution.

- Developed functionalism:

- Focused on the purpose of mental activities and behaviors.

- Studied how behavior helps organisms adapt to their environment.

- Emphasized studying the whole mind over parts.

-

D. Sigmund Freud and Psychoanalysis

-

-

- Freud (1856–1939): Austrian neurologist who developed psychoanalytic theory.

- Key Ideas:

- Unconscious mind: stores urges and feelings outside of awareness.

- Early childhood experiences shape adult behavior.

- Used dream analysis, slips of the tongue, and free association.

- Popularized talk therapy and the concept of the unconscious.

- Legacy: Still influences modern therapy and personality theory.

-

E. Gestalt Psychology

-

-

- Founded by Wertheimer, Koffka, & Köhler.

- “Gestalt” = whole; the mind perceives whole forms, not just parts.

- Emphasized how perception is more than the sum of its parts.

- Example: a melody is understood as a whole, not just as individual notes.

- Contrasted with structuralism, which focused on parts.

- Although less influential in the U.S., Gestalt principles still impact modern psychology, especially in sensation & perception.

-

F. Pavlov, Watson, Skinner, and Behaviorism

-

-

- Overview of Behaviorism

- Behaviorism largely responsible for establishing psychology as a scientific discipline.

- Dominated experimental psychology for decades and continues to be influential

- Used in behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Behavior modification is often used in classrooms.

- Behaviorism largely responsible for establishing psychology as a scientific discipline.

- Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936)

- Russian physiologist known for classical conditioning.

- Discovered that animals can learn to associate a neutral stimulus with a reflexive response.

- Key Concept: Conditioned reflex (learning through association).

- John B. Watson (1878-1958)

- American psychologist; founder of behaviorism.

- Believed psychology should only study observable behavior.

- Famous for advocating control and prediction of behavior using experimental methods.

- Often used animal models to study behavior.

- B.F. Skinner (1904-1990)

- Developed operant conditioning: learning through rewards and punishments.

- Invented the Skinner box to study how consequences shape behavior.

- Introduced terms: reinforcement, punishment, conditioning.

- Overview of Behaviorism

-

G. Humanism

-

-

- Abraham Maslow (1908–1970)

- Proposed the Hierarchy of Needs.

- Focused on self-actualization: reaching one’s full potential.

- Rejected behaviorism and psychoanalysis for being too deterministic.

- Carl Rogers (1902–1987)

- Developed client-centered therapy.

- Emphasized unconditional positive regard, empathy, and genuineness from therapists.

- Believed people are inherently good and capable of growth.

- Abraham Maslow (1908–1970)

-

H. The Cognitive Revolution

-

-

- Overview

- Shift in the 1950s–60s away from behaviorism to focus on mental processes like memory, perception, and thinking.

- Interdisciplinary: Combined psychology with computer science, linguistics, neuroscience, etc.

- Key Figures:

- Frederic Bartlett: Believed memory is constructive, influenced by prior knowledge.

- Jerome Bruner: Founded cognitive psychology, emphasized holistic understanding of thought.

- George Miller: Known for “The Magic Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two” — limits of working memory.

- Overview

-

I. Multicultural and Cross-Cultural Psychology

-

-

- Definitions:

- Multicultural Psychology: Studies behavior in diverse groups within one country.

- Cross-Cultural Psychology: Compares behavior across different countries and cultures.

- Key Figures:

- Francis Cecil Sumner: First African American with a PhD in psychology.

- Mamie & Kenneth Clark: Studied doll preferences in African American children; influenced Brown v. Board of Education.

- George I. Sanchez: Challenged bias in IQ testing for Mexican American children.

- Definitions:

-

J. Women in Psychology

-

-

- Trailblazers:

- Mary Whiton Calkins: Completed PhD at Harvard but denied degree due to gender; studied memory.

- Margaret Floy Washburn: First woman to receive PhD in psychology; wrote The Animal Mind.

- Mary Cover Jones: Known for deconditioning fear in children.

- Ethnic Minority Women:

- Martha Bernal: First Latina PhD in psychology; worked with Mexican American children.

- Inez Beverly Prosser: First African American woman to earn a psychology PhD; focused on education.

- Trailblazers:

-

3. Contemporary Psychology

A. Overview

-

-

- Contemporary psychology is diverse and shaped by many historical perspectives.

- The American Psychological Association (APA) is the largest organization of psychologists, with 56 divisions (e.g., Sport Psychology, Behavioral Neuroscience).

- The Association for Psychological Science (APS), founded in 1988, focuses on scientific research and publishing.

- Specialized groups like NLPA, AAPA, ABPsi, and SIP promote psychology within specific ethnic/racial communities.

-

B. Biopsychology

-

-

- Biopsychology studies how biology influences behavior, especially focusing on the nervous system.

- Areas: sensory/motor systems, sleep, drugs, development, psychological disorders.

- Part of the larger field of neuroscience.

- Evolutionary Psychology examines how behavior is shaped by evolution and natural selection.

- Behaviors must have a genetic basis to evolve.

- Example: Buss (1989) found cross-cultural differences in mate preferences based on evolutionary predictions.

- Challenge: Hard to know the exact past conditions when behaviors evolved.

- Behaviors must have a genetic basis to evolve.

- Biopsychology studies how biology influences behavior, especially focusing on the nervous system.

-

C. Sensation and Perception

-

-

- Sensation and perception study how we receive and interpret sensory information.

- Sensation = raw sensory input (sights, sounds, smells).

- Perception = how we interpret and make sense of those sensations.

- Influences: attention, past experiences, cultural background.

- Sensation and perception study how we receive and interpret sensory information.

-

D. Cognitive Psychology

-

-

- Cognitive psychology studies thoughts (cognitions) and how they relate to experiences and actions.

- Areas of interest: attention, problem-solving, language, memory.

- Cognitive psychology often overlaps with other fields, forming cognitive science.

-

E. Personality Psychology

-

-

- Personality psychology studies patterns of thoughts and behaviors that make individuals unique.

- Early theorists: Freud, Maslow, Allport.

- Modern research focuses on personality traits, measured through the Big Five (Five Factor Model):

- Conscientiousness

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism

- Openness

- Extraversion

- Traits are stable over the lifespan and influenced by genetics.

-

F. Social Psychology

-

-

- Social psychology studies how individuals interact with and relate to others.

- Topics: behavior explanation, prejudice, attraction, conflict resolution.

- Famous study: Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiment (1960s)

- Found most people obey authority figures even against their own morals.

- Led to stronger ethical standards in psychological research, including informed consent and minimizing deception.

-

G. Industrial/Organizational Psychology (I/O Psychology)

-

-

- I/O psychology applies psychological theories and research to workplace settings.

-

Includes both applied work and scientific research on behavior at work.

- Key Roles:

- Personnel management (hiring decisions)

- Improving organizational structure and workplace environment

- Enhancing employee productivity and efficiency

-

H. Health Psychology

-

-

- Health psychology focuses on how biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors influence health.

- Uses a biopsychosocial model (interaction of body, mind, and environment).

- Conducts research on genetics, behavior, stress, and health outcomes

- Develops interventions and public policies to promote better health behaviors

-

I. Sports and Exercise Psychology

-

-

- Studies psychological aspects of physical performance and exercise.

- Key Topics

- Motivation and performance anxiety

- Effects of physical activity on mental and emotional wellbeing

- Broader Applications: Applies to high-pressure fields like firefighting, military, surgery, and performing arts.

-

J. Clinical Psychology

-

-

- Focuses on diagnosing and treating psychological disorders and behavioral problems.

- Related Field: Counseling Psychology — focuses on emotional, social, and vocational wellbeing in healthy individuals.

- Influences:

- Freud: Psychoanalytic theory (still seen in psychodynamic therapy)

- Rogers: Client-centered therapy

- Behaviorism & Cognitive Revolution: Led to behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

-

K. Forensic Psychology

-

-

- Applies psychology within the legal and justice system.

- Key Roles:

- Assess competency to stand trial and mental state of defendants

- Consult on child custody, sentencing, and treatment

- Provide expert testimony in court

- Assist with jury selection and witness preparation

- Provide treatment within the criminal justice system

- Specialty: Criminal profiling (a smaller, specialized role)

-

4. Careers in Psychology

A. Education and Training in Psychology

-

-

- Advanced Degrees Required:

- Most psychology careers require at least a Master’s degree; many require a Doctoral degree (PhD or PsyD).

- PhD (Doctor of Philosophy):

- Focuses on research and academic careers.

- Requires completion of a dissertation (original research project).

- Often involves defending the dissertation before a panel of experts.

- Faculty Roles at Universities:

- Involve teaching, research, and service.

- Time spent on each varies by institution.

- Some faculty members focus exclusively on research (especially at large universities).

- Adjunct Faculty:

- Often hold a master’s degree.

- Teach part-time, sometimes alongside another career.

- Postdoctoral Training:

- After earning a PhD, some pursue postdoctoral programs to enhance research skills before becoming full-time faculty.

- Advanced Degrees Required:

-

B. Career Options Outside Academia

-

-

- PsyD (Doctor of Psychology):

- Focuses more on clinical work rather than research.

- Popular for those interested in clinical psychology careers.v

- Licensure for Clinical and Counseling Psychologists:

- Requires supervised postdoctoral work (in most states).

- Must pass a licensure exam.

- Clinical Psychologists (PhD/PsyD) vs. Psychiatrists (MD):

- Psychologists: Therapy, psychological testing.

- Psychiatrists: Therapy and can prescribe medications.

- Examples of Career Settings:

- Private practice

- Hospitals

- Legal system (forensic psychology)

- Pharmaceutical companies (biopsychology research)

- PsyD (Doctor of Psychology):

-

C. Careers with a Master’s Degree in Psychology

-

-

- Professional Counselor (provides psychotherapy)

- School Psychologist

- Sport Psychology Roles