5

CHAPTER OUTLINE

5.1 Sensation versus Perception

5.2 Waves and Wavelengths

5.3 Vision

5.4 Hearing

5.5 The Other Senses

5.6 Gestalt Principles of Perception

INTRODUCTION: Imagine standing on a city street corner. You might be struck by movement everywhere as cars and people go about their business, by the sound of a street musician’s melody or a horn honking in the distance, by the smell of exhaust fumes or of food being sold by a nearby vendor, and by the sensation of hard pavement under your feet.

We rely on our sensory systems to provide important information about our surroundings. We use this information to successfully navigate and interact with our environment so that we can find nourishment, seek shelter, maintain social relationships, and avoid potentially dangerous situations.

This chapter will provide an overview of how sensory information is received and processed by the nervous system and how that affects our conscious experience of the world. We begin by learning the distinction between sensation and perception. Then we consider the physical properties of light and sound stimuli, along with an overview of the basic structure and function of the major sensory systems. The chapter will close with a discussion of a historically important theory of perception called Gestalt.

5.1 Sensation and Perception

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Differentiate the processes of sensation and perception

- Describe the basic principles of sensation and perception

- Describe the function of each of our senses

Sensation

Perception

While our sensory receptors are constantly collecting information from the environment, it is ultimately how we interpret that information that affects how we interact with the world. Remember that perception refers to the way sensory information is organized, interpreted, and consciously experienced. One way to think of the processes of sensation and perception is to note that sensation is a physical process, whereas perception is psychological. For example, upon walking into a kitchen and smelling the scent of baking cinnamon rolls, the sensation is the scent receptors detecting the odor of cinnamon, but the perception may be “Mmm, this smells like the bread Grandma used to bake when the family gathered for holidays.”

Perception involves both bottom-up and top-down processing. Bottom-up processing refers to sensory information from a stimulus in the environment driving a process, and top-down processing refers to knowledge and expectancy driving a process. The best way to illustrate these two concepts is with our ability to read. Read the quote found in Figure 5.2 (a) out loud:

Notice anything odd while you were reading the text in the triangle? Did you notice the second “the”? If not, it’s likely because you were reading this from a top-down approach. Having a second “the” doesn’t make sense. We know this. Our brain knows this and doesn’t expect there to be a second one, so we have a tendency to skip right over it. In other words, your past experience has changed the way you perceive the writing in the triangle! A beginning reader—one who is using a bottom-up approach by carefully attending to each piece—would be less likely to make this error.[4]

Finally, it should be noted that when we experience a sensory stimulus that doesn’t change, we stop paying attention to it. This is why we don’t feel the weight of our clothing, hear the hum of a projector in a lecture hall, or see all the tiny scratches on the lenses of our glasses. When a stimulus is constant and unchanging, we experience sensory adaptation. This occurs because if a stimulus does not change, our receptors quit responding to it. A great example of this occurs when we leave the radio on in our car after we park it at home for the night. When we listen to the radio on the way home from work the volume seems reasonable. However, the next morning when we start the car, we might be startled by how loud the radio is. We don’t remember it being that loud last night. What happened? We adapted to the constant stimulus (the radio volume) over the course of the previous day and increased the volume at various times.[5]

There is another factor that affects sensation and perception: attention. Attention plays a significant role in determining what is sensed versus what is perceived. Imagine you are at a party full of music, chatter, and laughter. You get involved in an interesting conversation with a friend, and you tune out all the background noise. If someone interrupted you to ask what song had just finished playing, you would probably be unable to answer that question.

One of the most interesting demonstrations of how important attention is in determining our perception of the environment occurred in a famous study conducted by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris (1999). In this study, participants watched a video of people dressed in black and white passing basketballs. Participants were asked to count the number of times the team dressed in white passed the ball. During the video, a person dressed in a black gorilla costume walks among the two teams. You would think that someone would notice the gorilla, right? Nearly half of the people who watched the video didn’t notice the gorilla at all, despite the fact that he was clearly visible for nine seconds. Because participants were so focused on the number of times the team dressed in white was passing the ball, they completely tuned out other visual information. Inattentional blindness is the failure to notice something that is completely visible because the person was actively attending to something else and did not pay attention to other things (Mack & Rock, 1998; Simons & Chabris, 1999).

In a similar experiment, researchers tested inattentional blindness by asking participants to observe images moving across a computer screen. They were instructed to focus on either white or black objects, disregarding the other color. When a red cross passed across the screen, about one third of subjects did not notice it (Figure 5.3) (Most, Simons, Scholl, & Chabris, 2000).

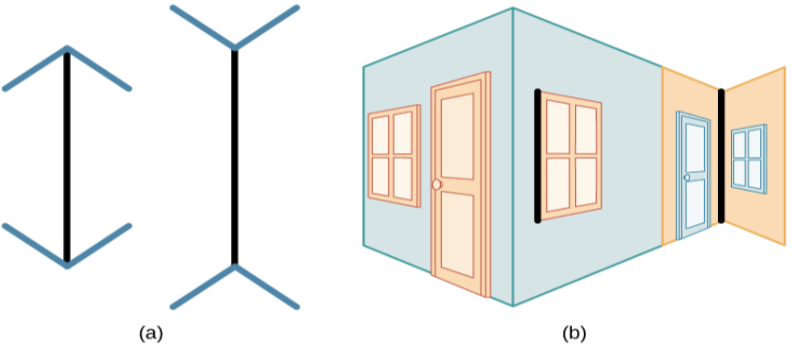

Our perceptions can also be affected by our beliefs, values, prejudices, expectations, and life experiences. As you will see later in this chapter, individuals who are deprived of the experience of binocular vision during critical periods of development have trouble perceiving depth (Fawcett, Wang, & Birch, 2005). The shared experiences of people within a given cultural context can have pronounced effects on perception. For example, Marshall Segall, Donald Campbell, and Melville Herskovits (1963) published the results of a multinational study in which they demonstrated that individuals from Western cultures were more prone to experience certain types of visual illusions than individuals from non-Western cultures, and vice versa. One such illusion that Westerners were more likely to experience was the Müller-Lyer illusion (Figure 5.4): The lines appear to be different lengths, but they are actually the same length.

Children described as thrill seekers are more likely to show taste preferences for intense sour flavors (Liem, Westerbeek, Wolterink, Kok, & de Graaf, 2004), which suggests that basic aspects of personality might affect perception. Furthermore, individuals who hold positive attitudes toward reduced-fat foods are more likely to rate foods labeled as reduced fat as tasting better than people who have less positive attitudes about these products (Aaron, Mela, & Evans, 1994).

5.1 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 5.1 Sensation versus Perception

Sensation occurs when sensory receptors detect sensory stimuli. Perception involves the organization, interpretation, and conscious experience of those sensations. All sensory systems have both absolute and difference thresholds, which refer to the minimum amount of stimulus energy or the minimum amount of difference in stimulus energy required to be detected about 50% of the time, respectively. Sensory adaptation, selective attention, and signal detection theory can help explain what is perceived and what is not. In addition, our perceptions are affected by a number of factors, including beliefs, values, prejudices, culture, and life experiences.

5.2 Waves and Wavelengths

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe important physical features of wave forms

- Show how physical properties of light waves are associated with perceptual experience

- Show how physical properties of sound waves are associated with perceptual experience

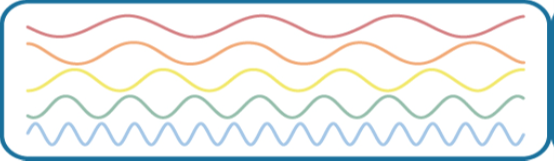

Visual and auditory stimuli both occur in the form of waves. Although the two stimuli are very different in terms of composition, wave forms share similar characteristics that are especially important to our visual and auditory perceptions. In this section, we describe the physical properties of the waves as well as the perceptual experiences associated with them.

Amplitude and Wavelength

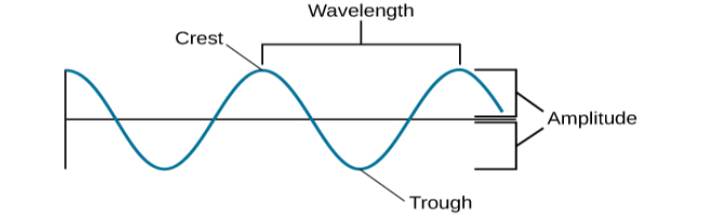

Two physical characteristics of a wave are amplitude and wavelength (Figure 5.5). The amplitude of a wave is the distance from the center line to the top point of the crest or the bottom point of the trough. Wavelength refers to the length of a wave from one peak to the next.

Light Waves

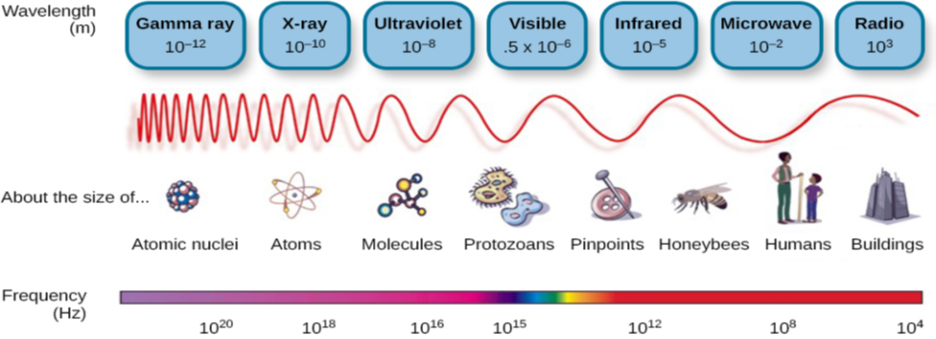

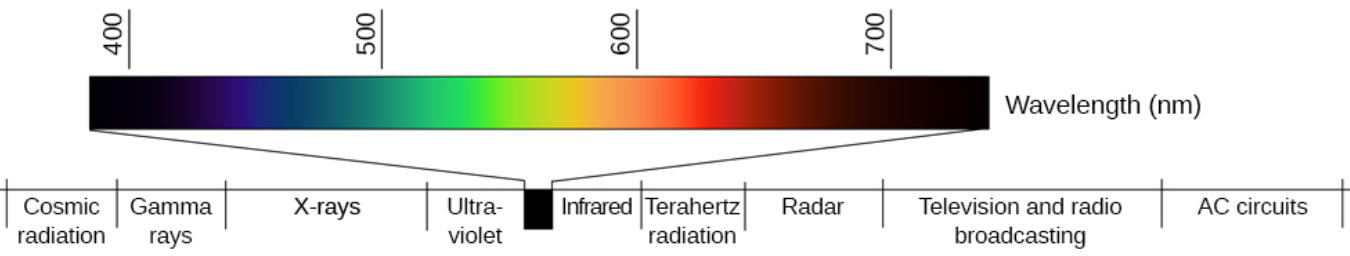

The visible spectrum is the portion of the larger electromagnetic spectrum that we can see. As Figure 5.7 shows, the electromagnetic spectrum encompasses all of the electromagnetic radiation that occurs in our environment and includes gamma rays, x-rays, ultraviolet light, visible light, infrared light, microwaves, and radio waves. The visible spectrum in humans is associated with wavelengths that range from 380 to 740 nm—a very small distance, since a nanometer (nm) is one billionth of a meter. Other species can detect other portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. For instance, honeybees can see light in the ultraviolet range (Wakakuwa, Stavenga, & Arikawa, 2007), and some snakes can detect infrared radiation in addition to more traditional visual light cues (Chen, Deng, Brauth, Ding, & Tang, 2012; Hartline, Kass, & Loop, 1978).

Sound Waves

Like light waves, the physical properties of sound waves are associated with various aspects of our perception of sound. The frequency of a sound wave is associated with our perception of that sound’s pitch. High-frequency sound waves are perceived as high-pitched sounds, while low-frequency sound waves are perceived as low-pitched sounds. The audible range of sound frequencies is between 20 and 20000 Hz, with greatest sensitivity to those frequencies that fall in the middle of this range.

As was the case with the visible spectrum, other species show differences in their audible ranges. For instance, chickens have a very limited audible range, from 125 to 2000 Hz. Mice have an audible range from 1000 to 91000 Hz, and the beluga whale’s audible range is from 1000 to 123000 Hz. Our pet dogs and cats have audible ranges of about 70–45000 Hz and 45–64000 Hz, respectively (Strain, 2003).

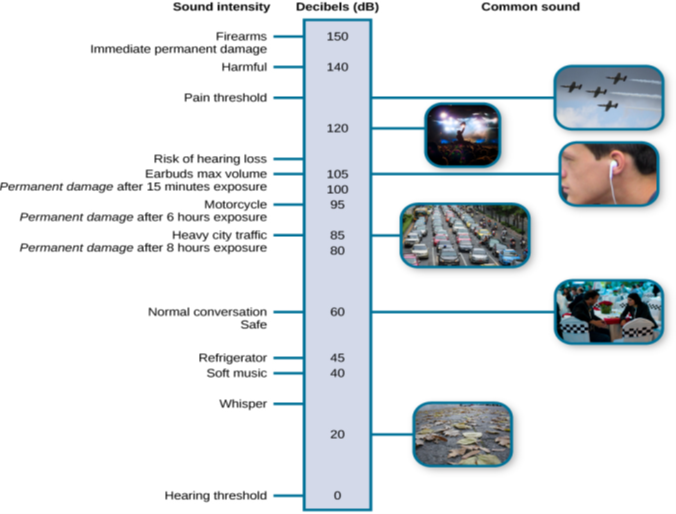

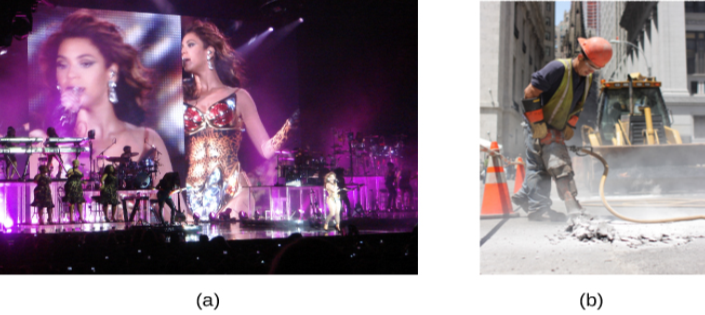

The loudness of a given sound is closely associated with the amplitude of the sound wave. Higher amplitudes are associated with louder sounds. Loudness is measured in terms of decibels (dB), a logarithmic unit of sound intensity. A typical conversation would correlate with 60 dB; a rock concert might check in at 120 dB (Figure 5.9). A whisper 5 feet away or rustling leaves are at the low end of our hearing range; sounds like a window air conditioner, a normal conversation, and even heavy traffic or a vacuum cleaner are within a tolerable range. However, there is the potential for hearing damage from about 80 dB to 130 dB: These are sounds of a food processor, power lawnmower, heavy truck (25 feet away), subway train (20 feet away), live rock music, and a jackhammer. About one-third of all hearing loss is due to noise exposure, and the louder the sound, the shorter the exposure needed to cause hearing damage (Le, Straatman, Lea, & Westerberg, 2017). Listening to music through earbuds at maximum volume (around 100–105 decibels) can cause noise-induced hearing loss after 15 minutes of exposure. Although listening to music at maximum volume may not seem to cause damage, it increases the risk of age-related hearing loss (Kujawa & Liberman, 2006). The threshold for pain is about 130 dB, a jet plane taking off or a revolver firing at close range (Dunkle, 1982).

Of course, different musical instruments can play the same musical note at the same level of loudness, yet they still sound quite different. This is known as the timbre of a sound. Timbre refers to a sound’s purity, and it is affected by the complex interplay of frequency, amplitude, and timing of sound waves.

5.2 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 5.2 Waves and Wavelengths

Both light and sound can be described in terms of wave forms with physical characteristics like amplitude, wavelength, and timbre. Wavelength and frequency are inversely related so that longer waves have lower frequencies, and shorter waves have higher frequencies. In the visual system, a light wave’s wavelength is generally associated with color, and its amplitude is associated with brightness. In the auditory system, a sound’s frequency is associated with pitch, and its amplitude is associated with loudness.

5.3 Vision

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the basic anatomy of the visual system

- Discuss how rods and cones contribute to different aspects of vision

- Describe how monocular and binocular cues are used in the perception of depth

The visual system constructs a mental representation of the world around us (Figure 5.10). This contributes to our ability to successfully navigate through physical space and interact with important individuals and objects in our environments. This section will provide an overview of the basic anatomy and function of the visual system. In addition, we will explore our ability to perceive color and depth.

Anatomy of the Visual System

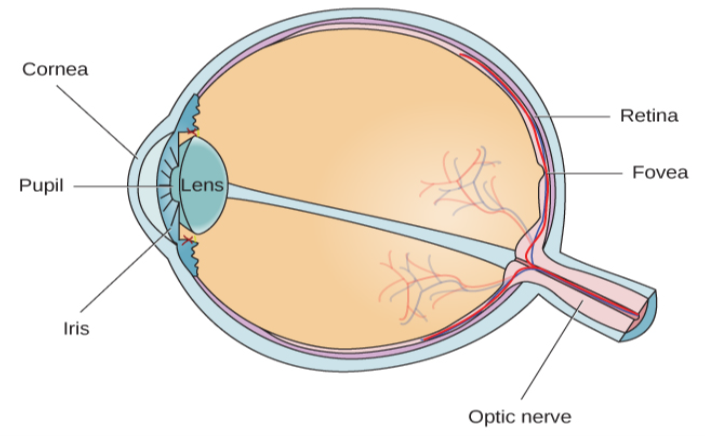

The eye is the major sensory organ involved in vision (Figure 5.11). Light waves are transmitted across the cornea and enter the eye through the pupil. The cornea is the transparent covering over the eye. It serves as a barrier between the inner eye and the outside world, and it is involved in focusing light waves that enter the eye. The pupil is the small opening in the eye through which light passes, and the size of the pupil can change as a function of light levels as well as emotional arousal. When light levels are low, the pupil will become dilated, or expanded, to allow more light to enter the eye. When light levels are high, the pupil will constrict, or become smaller, to reduce the amount of light that enters the eye. The pupil’s size is controlled by muscles that are connected to the iris, which is the colored portion of the eye.

While cones are concentrated in the fovea, where images tend to be focused, rods, another type of photoreceptor, are located throughout the remainder of the retina. Rods are specialized photoreceptors that work well in low light conditions, and while they lack the spatial resolution and color function of the cones, they are involved in our vision in dimly lit environments as well as in our perception of movement on the periphery of our visual field.

Rods and cones are connected (via several interneurons) to retinal ganglion cells. Axons from the retinal ganglion cells converge and exit through the back of the eye to form the optic nerve. The optic nerve carries visual information from the retina to the brain. There is a point in the visual field called the blind spot: Even when light from a small object is focused on the blind spot, we do not see it. We are not consciously aware of our blind spots for two reasons: First, each eye gets a slightly different view of the visual field; therefore, the blind spots do not overlap. Second, our visual system fills in the blind spot so that although we cannot respond to visual information that occurs in that portion of the visual field, we are also not aware that information is missing.

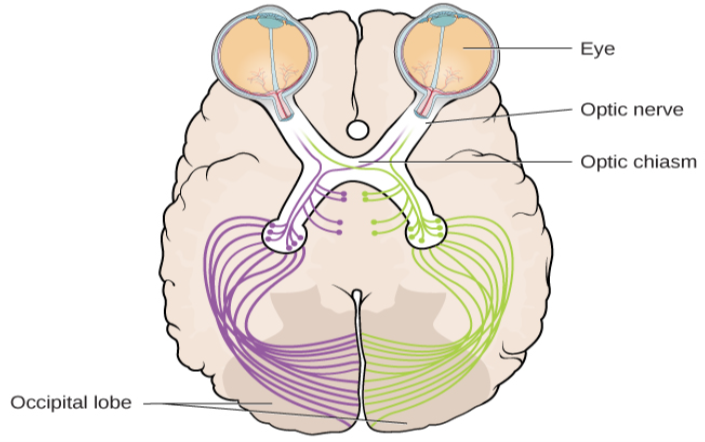

The optic nerve from each eye merges just below the brain at a point called the optic chiasm. As Figure 5.13 shows, the optic chiasm is an X-shaped structure that sits just below the cerebral cortex at the front of the brain. At the point of the optic chiasm, information from the right visual field (which comes from both eyes) is sent to the left side of the brain, and information from the left visual field is sent to the right side of the brain.

Color and Depth Perception

We do not see the world in black and white; neither do we see it as two-dimensional (2-D) or flat (just height and width, no depth). Let’s look at how color vision works and how we perceive three dimensions (height, width, and depth).

Color Vision

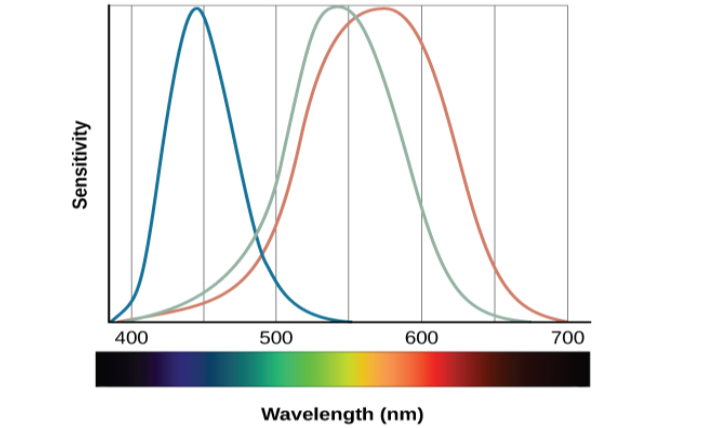

Normal-sighted individuals have three different types of cones that mediate color vision. Each of these cone types is maximally sensitive to a slightly different wavelength of light. According to the trichromatic theory of color vision, shown in Figure 5.14, all colors in the spectrum can be produced by combining red, green, and blue. The three types of cones are each receptive to one of the colors.

The trichromatic theory of color vision is not the only theory—another major theory of color vision is known as the opponent-process theory. According to this theory, color is coded in opponent pairs: black-white, yellow-blue, and green-red. The basic idea is that some cells of the visual system are excited by one of the opponent colors and inhibited by the other. So, a cell that was excited by wavelengths associated with green would be inhibited by wavelengths associated with red, and vice versa. One of the implications of opponent processing is that we do not experience greenish-reds or yellowish-blues as colors. Another implication is that this leads to the experience of negative afterimages. An afterimage describes the continuation of a visual sensation after removal of the stimulus. For example, when you stare briefly at the sun and then look away from it, you may still perceive a spot of light although the stimulus (the sun) has been removed. When color is involved in the stimulus, the color pairings identified in the opponent-process theory lead to a negative afterimage. You can test this concept using the flag in Figure 5.15.

Color Blindness: A Personal Story

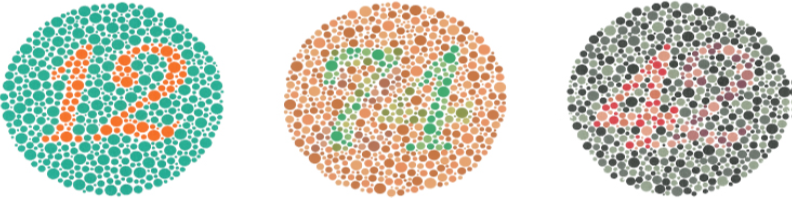

Several years ago, I dressed to go to a public function and walked into the kitchen where my 7-year-old daughter sat. She looked up at me, and in her most stern voice, said, “You can’t wear that.” I asked, “Why not?” and she informed me the colors of my clothes did not match. She had complained frequently that I was bad at matching my shirts, pants, and ties, but this time, she sounded especially alarmed. As a single father with no one else to ask at home, I drove us to the nearest convenience store and asked the store clerk if my clothes matched. She said my pants were a bright green color, my shirt was a reddish-orange, and my tie was brown. She looked at my quizzically and said, “No way do your clothes match.” Over the next few days, I started asking my coworkers and friends if my clothes matched. After several days of being told that my coworkers just thought I had “a really unique style,” I made an appointment with an eye doctor and was tested (Figure 5.16). It was then that I found out that I was colorblind. I cannot differentiate between most greens, browns, and reds. Fortunately, other than unknowingly being badly dressed, my colorblindness rarely harms my day-to-day life.

Depth Perception

Our ability to perceive spatial relationships in three-dimensional (3-D) space is known as depth perception. With depth perception, we can describe things as being in front, behind, above, below, or to the side of other things.

Our world is three-dimensional, so it makes sense that our mental representation of the world has three-dimensional properties. We use a variety of cues in a visual scene to establish our sense of depth. Some of these are binocular cues, which means that they rely on the use of both eyes. One example of a binocular depth cue is binocular disparity, the slightly different view of the world that each of our eyes receives. To experience this slightly different view, do this simple exercise: extend your arm fully and extend one of your fingers and focus on that finger. Now, close your left eye without moving your head, then open your left eye and close your right eye without moving your head. You will notice that your finger seems to shift as you alternate between the two eyes because of the slightly different view each eye has of your finger.

A 3-D movie works on the same principle: the special glasses you wear allow the two slightly different images projected onto the screen to be seen separately by your left and your right eye. As your brain processes these images, you have the illusion that the leaping animal or running person is coming right toward you.

Although we rely on binocular cues to experience depth in our 3-D world, we can also perceive depth in 2-D arrays. Think about all the paintings and photographs you have seen. Generally, you pick up on depth in these images even though the visual stimulus is 2-D. When we do this, we are relying on a number of monocular cues, or cues that require only one eye. If you think you can’t see depth with one eye, note that you don’t bump into things when using only one eye while walking—and, in fact, we have more monocular cues than binocular cues.

An example of a monocular cue would be what is known as linear perspective. Linear perspective refers to the fact that we perceive depth when we see two parallel lines that seem to converge in an image (Figure 5.17). Some other monocular depth cues are interposition, the partial overlap of objects, and the relative size and closeness of images to the horizon.

DIG DEEPER

Stereoblindness

Bruce Bridgeman was born with an extreme case of lazy eye that resulted in him being stereoblind, or unable to respond to binocular cues of depth. He relied heavily on monocular depth cues, but he never had a true appreciation of the 3-D nature of the world around him. This all changed one night in 2012 while Bruce was seeing a movie with his wife.

The movie the couple was going to see was shot in 3-D, and even though he thought it was a waste of money, Bruce paid for the 3-D glasses when he purchased his ticket. As soon as the film began, Bruce put on the glasses and experienced something completely new. For the first time in his life he appreciated the true depth of the world around him. Remarkably, his ability to perceive depth persisted outside of the movie theater.

There are cells in the nervous system that respond to binocular depth cues. Normally, these cells require activation during early development in order to persist, so experts familiar with Bruce’s case (and others like his) assume that at some point in his development, Bruce must have experienced at least a fleeting moment of binocular vision. It was enough to ensure the survival of the cells in the visual system tuned to binocular cues. The mystery now is why it took Bruce nearly 70 years to have these cells activated (Peck, 2012).

5.3 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 5.3 Vision

Light waves cross the cornea and enter the eye at the pupil. The eye’s lens focuses this light so that the image is focused on a region of the retina known as the fovea. The fovea contains cones that possess high levels of

visual acuity and operate best in bright light conditions. Rods are located throughout the retina and operate best under dim light conditions. Visual information leaves the eye via the optic nerve. Information from each visual field is sent to the opposite side of the brain at the optic chiasm. Visual information then moves through a number of brain sites before reaching the occipital lobe, where it is processed.

Two theories explain color perception. The trichromatic theory asserts that three distinct cone groups are tuned to slightly different wavelengths of light, and it is the combination of activity across these cone types that results in our perception of all the colors we see. The opponent-process theory of color vision asserts that color is processed in opponent pairs and accounts for the interesting phenomenon of a negative afterimage. We perceive depth through a combination of monocular and binocular depth cues.

5.4 Hearing

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the basic anatomy and function of the auditory system

- Explain how we encode and perceive pitch

- Discuss how we localize sound

Some of the most well-known celebrities and top earners in the world are musicians. Our worship of musicians may seem silly when you consider that all they are doing is vibrating the air a certain way to create sound waves, the physical stimulus for audition.[6]

Anatomy of the Auditory System

People are capable of getting a large amount of information from the basic qualities of sound waves. The amplitude (or intensity) of a sound wave codes for the loudness of a stimulus; higher amplitude sound waves result in louder sounds. The pitch of a stimulus is coded in the frequency of a sound wave; higher frequency sounds are higher pitched. We can also gauge the quality, or timbre, of a sound by the complexity of the sound wave. This allows us to tell the difference between bright and dull sounds as well as natural and synthesized instruments (Välimäki & Takala, 1996).

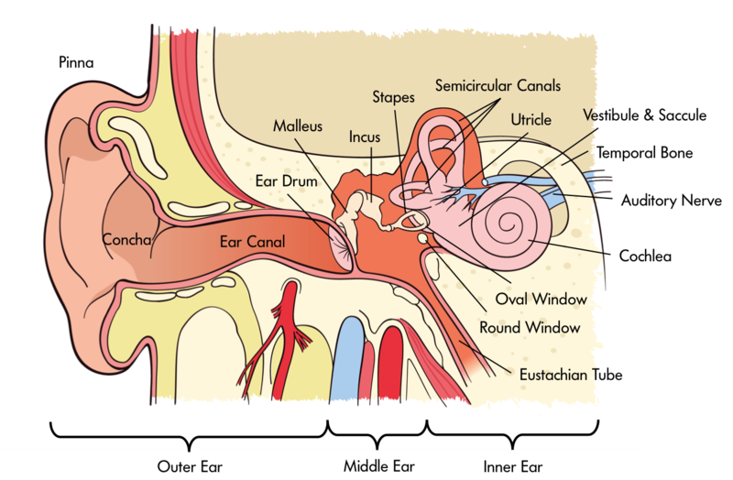

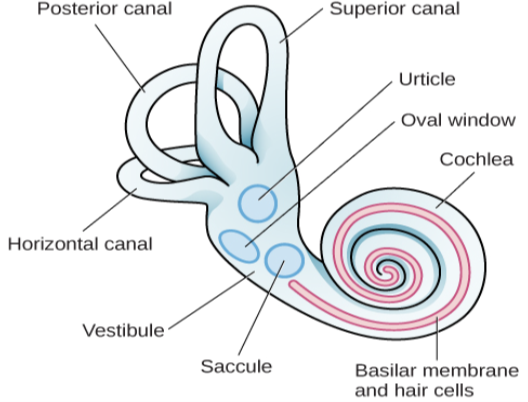

In order for us to sense sound waves from our environment they must reach our inner ear. Lucky for us, we have evolved tools that allow those waves to be funneled and amplified during this journey. Initially, sound waves are funneled by your pinna (the external part of your ear that you can actually see) into your auditory canal (the hole you stick Q-tips into despite the box advising against it). During their journey, sound waves eventually reach a thin, stretched membrane called the tympanic membrane (eardrum), which vibrates against the three smallest bones in the body—the malleus (hammer), the incus (anvil), and the stapes (stirrup)—collectively called the ossicles. Both the tympanic membrane and the ossicles amplify the sound waves before they enter the fluid-filled cochlea, a snail-shell-like bone structure containing auditory hair cells arranged on the basilar membrane (see Figure 4) according to the frequency they respond to (called tonotopic organization). Depending on age, humans can normally detect sounds between 20 Hz and 20 kHz. It is inside the cochlea that sound waves are converted into an electrical message (Figure 5.18).

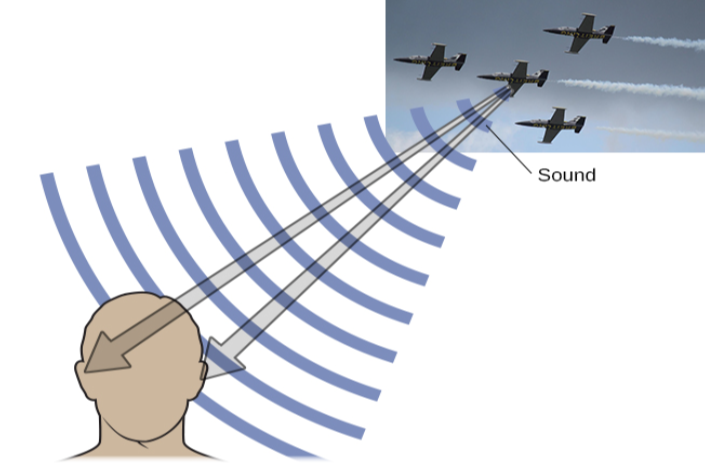

Because we have an ear on each side of our head, we are capable of localizing sound in 3D space pretty well (in the same way that having two eyes produces 3D vision). Have you ever dropped something on the floor without seeing where it went? Did you notice that you were somewhat capable of locating this object based on the sound it made when it hit the ground? We can reliably locate something based on which ear receives the sound first. What about the height of a sound? If both ears receive a sound at the same time, how are we capable of localizing sound vertically? Research in cats (Populin & Yin, 1998) and humans (Middlebrooks & Green, 1991) has pointed to differences in the quality of sound waves depending on vertical positioning.

After being processed by auditory hair cells, electrical signals are sent through the cochlear nerve (a division of the vestibulocochlear nerve) to the thalamus, and then the primary auditory cortex of the temporal lobe. Interestingly, the tonotopic organization of the cochlea is maintained in this area of the cortex (Merzenich, Knight, & Roth, 1975; Romani, Williamson, & Kaufman, 1982). However, the role of the primary auditory cortex in processing the wide range of features of sound is still being explored (Walker, Bizley, & Schnupp, 2011).[7]

Pitch Perception

As described above, different frequencies of sound waves are associated with differences in our perception of the pitch of those sounds. Low-frequency sounds are lower pitched, and high-frequency sounds are higher pitched. How does the auditory system differentiate among various pitches?

Several theories have been proposed to account for pitch perception. We’ll discuss two of them here: temporal theory and place theory. The temporal theory of pitch perception asserts that frequency is coded by the activity level of a sensory neuron. This would mean that a given hair cell would fire action potentials related to the frequency of the sound wave. While this is a very intuitive explanation, we detect such a broad range of frequencies (20–20,000 Hz) that the frequency of action potentials fired by hair cells cannot account for the entire range. Because of properties related to sodium channels on the neuronal membrane that are involved in action potentials, there is a point at which a cell cannot fire any faster (Shamma, 2001).

The place theory of pitch perception suggests that different portions of the basilar membrane are sensitive to sounds of different frequencies. More specifically, the base of the basilar membrane responds best to high frequencies and the tip of the basilar membrane responds best to low frequencies. Therefore, hair cells that are in the base portion would be labeled as high-pitch receptors, while those in the tip of basilar membrane would be labeled as low-pitch receptors (Shamma, 2001).

In reality, both theories explain different aspects of pitch perception. At frequencies up to about 4000 Hz, it is clear that both the rate of action potentials and place contribute to our perception of pitch. However, much higher frequency sounds can only be encoded using place cues (Shamma, 2001).

Sound Localization

Also introduced above was how localizing sound could be considered similar to the way that we perceive depth in our visual fields. Like the monocular and binocular cues that provided information about depth, the auditory system uses both monaural (one-eared) and binaural (two-eared) cues to localize sound.

Each pinna interacts with incoming sound waves differently, depending on the sound’s source relative to our bodies. This interaction provides a monaural cue that is helpful in locating sounds that occur above or below and in front or behind us. The sound waves received by your two ears from sounds that come from directly above, below, in front, or behind you would be identical; therefore, monaural cues are essential (Grothe, Pecka, & McAlpine, 2010).

Binaural cues, on the other hand, provide information on the location of a sound along a horizontal axis by relying on differences in patterns of vibration of the eardrum between our two ears. If a sound comes from an off-center location, it creates two types of binaural cues: interaural level differences and interaural timing differences. Interaural level difference refers to the fact that a sound coming from the right side of your body is more intense at your right ear than at your left ear because of the attenuation of the sound wave as it passes through your head. Interaural timing difference refers to the small difference in the time at which a given sound wave arrives at each ear (Figure 5.19). Certain brain areas monitor these differences to construct where along a horizontal axis a sound originates (Grothe et al., 2010).

Deafness is the partial or complete inability to hear. Some people are born without hearing, which is known as congenital deafness. Other people suffer from conductive hearing loss, which is due to a problem delivering sound energy to the cochlea. Causes for conductive hearing loss include blockage of the ear canal, a hole in the tympanic membrane, problems with the ossicles, or fluid in the space between the eardrum and cochlea. Another group of people suffer from sensorineural hearing loss, which is the most common form of hearing loss. Sensorineural hearing loss can be caused by many factors, such as aging, head or acoustic trauma, infections and diseases (such as measles or mumps), medications, environmental effects such as noise exposure (noise-induced hearing loss, as shown in Figure 5.20), tumors, and toxins (such as those found in certain solvents and metals).

When the hearing problem is associated with a failure to transmit neural signals from the cochlea to the brain, it is called sensorineural hearing loss. One disease that results in sensorineural hearing loss is Ménière's disease. Although not well understood, Ménière’s disease results in a degeneration of inner ear structures that can lead to hearing loss, tinnitus (constant ringing or buzzing), vertigo (a sense of spinning), and an increase in pressure within the inner ear (Semaan & Megerian, 2011). This kind of loss cannot be treated with hearing aids, but some individuals might be candidates for a cochlear implant as a treatment option. Cochlear implants are electronic devices that consist of a microphone, a speech processor, and an electrode array. The device receives incoming sound information and directly stimulates the auditory nerve to transmit information to the brain.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

Deaf Culture

In the United States and other places around the world, deaf people have their own language, schools, and customs. This is called deaf culture. In the United States, deaf individuals often communicate using American Sign Language (ASL); ASL has no verbal component and is based entirely on visual signs and gestures. The primary mode of communication is signing. One of the values of deaf culture is to continue traditions like using sign language rather than teaching deaf children to try to speak, read lips, or have cochlear implant surgery.

When a child is diagnosed as deaf, parents have difficult decisions to make. Should the child be enrolled in mainstream schools and taught to verbalize and read lips? Or should the child be sent to a school for deaf children to learn ASL and have significant exposure to deaf culture? Do you think there might be differences in the way that parents approach these decisions depending on whether or not they are also deaf?

5.4 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 5.4 Hearing

Sound waves are funneled into the auditory canal and cause vibrations of the eardrum; these vibrations move the ossicles. As the ossicles move, the stapes presses against the oval window of the cochlea, which causes fluid

inside the cochlea to move. As a result, hair cells embedded in the basilar membrane become enlarged, which sends neural impulses to the brain via the auditory nerve.

Pitch perception and sound localization are important aspects of hearing. Our ability to perceive pitch relies on both the firing rate of the hair cells in the basilar membrane as well as their location within the membrane.

In terms of sound localization, both monaural and binaural cues are used to locate where sounds originate in our environment.

Individuals can be born deaf, or they can develop deafness as a result of age, genetic predisposition, and/or environmental causes. Hearing loss that results from a failure of the vibration of the eardrum or the resultant

movement of the ossicles is called conductive hearing loss. Hearing loss that involves a failure of the transmission of auditory nerve impulses to the brain is called sensorineural hearing loss.

5.5 The Other Senses

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the basic functions of the chemical senses

- Explain the basic functions of the somatosensory, nociceptive, and thermoreceptive sensory systems

- Describe the basic functions of the vestibular, proprioceptive, and kinesthetic sensory systems

Vision and hearing have received an incredible amount of attention from researchers over the years. While there is still much to be learned about how these sensory systems work, we have a much better understanding of them than of our other sensory modalities. In this section, we will explore our chemical senses (taste and smell) and our body senses (touch, temperature, pain, balance, and body position).

The Chemical Senses

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are called chemical senses because both have sensory receptors that respond to molecules in the food we eat or in the air we breathe. There is a pronounced interaction between our chemical senses. For example, when we describe the flavor of a given food, we are really referring to both gustatory and olfactory properties of the food working in combination.

Taste (Gustation)

You have learned since elementary school that there are four basic groupings of taste: sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. Research demonstrates, however, that we have at least six taste groupings. Umami is our fifth taste. Umami is actually a Japanese word that roughly translates to yummy, and it is associated with a taste for monosodium glutamate (Kinnamon & Vandenbeuch, 2009). There is also a growing body of experimental evidence suggesting that we possess a taste for the fatty content of a given food (Mizushige, Inoue, & Fushiki, 2007).

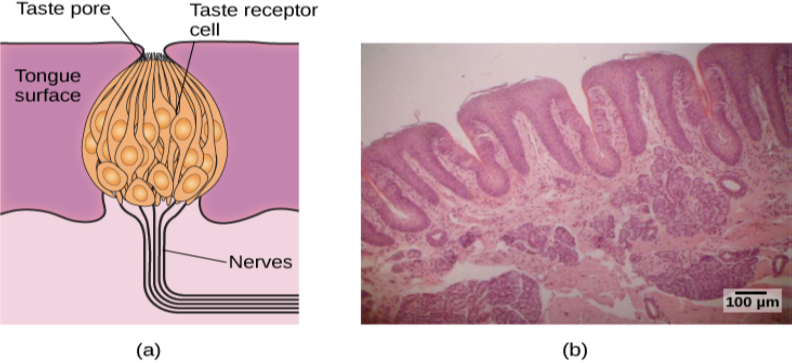

Molecules from the food and beverages we consume dissolve in our saliva and interact with taste receptors on our tongue and in our mouth and throat. Taste buds are formed by groupings of taste receptor cells with hair-like extensions that protrude into the central pore of the taste bud (Figure 5.21). Taste buds have a life cycle of ten days to two weeks, so even destroying some by burning your tongue won’t have any long-term effect; they just grow right back. Taste molecules bind to receptors on this extension and cause chemical changes within the sensory cell that result in neural impulses being transmitted to the brain via different nerves, depending on where the receptor is located. Taste information is transmitted to the medulla, thalamus, and limbic system, and to the gustatory cortex, which is tucked underneath the overlap between the frontal and temporal lobes (Maffei, Haley, & Fontanini, 2012; Roper, 2013).

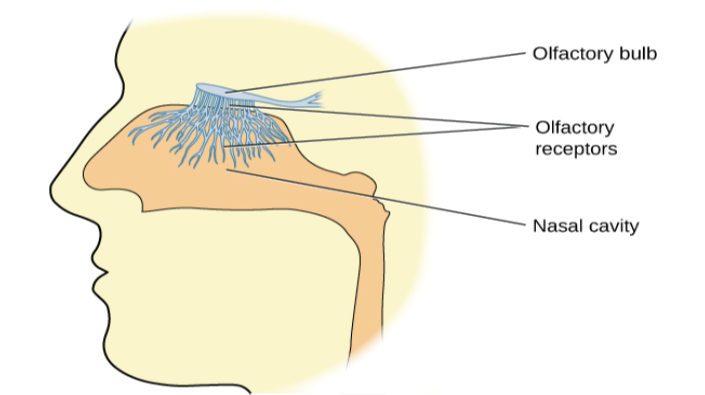

Olfactory receptor cells are located in a mucous membrane at the top of the nose. Small hair-like extensions from these receptors serve as the sites for odor molecules dissolved in the mucus to interact with chemical receptors located on these extensions (Figure 5.22). Once an odor molecule has bound a given receptor, chemical changes within the cell result in signals being sent to the olfactory bulb: a bulb-like structure at the tip of the frontal lobe where the olfactory nerves begin. From the olfactory bulb, information is sent to regions of the limbic system and to the primary olfactory cortex, which is located very near the gustatory cortex (Lodovichi & Belluscio, 2012; Spors et al., 2013).

Many species respond to chemical messages, known as pheromones, sent by another individual (Wysocki & Preti, 2004). Pheromonal communication often involves providing information about the reproductive status of a potential mate. So, for example, when a female rat is ready to mate, she secretes pheromonal signals that draw attention from nearby male rats. Pheromonal activation is actually an important component in eliciting sexual behavior in the male rat (Furlow, 1996, 2012; Purvis & Haynes, 1972; Sachs, 1997). There has also been a good deal of research (and controversy) about pheromones in humans (Comfort, 1971; Russell, 1976; Wolfgang-Kimball, 1992; Weller, 1998).

Touch, Thermoception, and Nociception

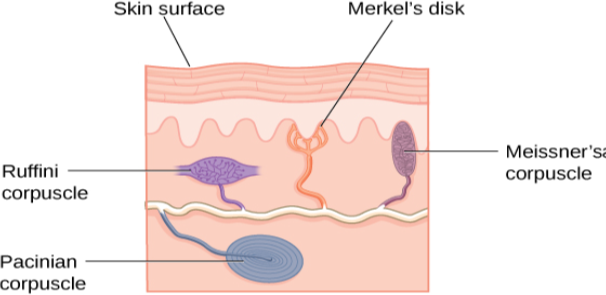

A number of receptors are distributed throughout the skin to respond to various touch-related stimuli (Figure 5.23). These receptors include Meissner’s corpuscles, Pacinian corpuscles, Merkel’s disks, and Ruffini corpuscles. Meissner’s corpuscles respond to pressure and lower frequency vibrations, and Pacinian corpuscles detect transient pressure and higher frequency vibrations. Merkel’s disks respond to light pressure, while Ruffini corpuscles detect stretch (Abraira & Ginty, 2013).

Pain Perception

Pain is an unpleasant experience that involves both physical and psychological components. Feeling pain is quite adaptive because it makes us aware of an injury, and it motivates us to remove ourselves from the cause of that injury. In addition, pain also makes us less likely to suffer additional injury because we will be gentler with our injured body parts.

Generally speaking, pain can be considered to be neuropathic or inflammatory in nature. Pain that signals some type of tissue damage is known as inflammatory pain. In some situations, pain results from damage to neurons of either the peripheral or central nervous system. As a result, pain signals that are sent to the brain get exaggerated. This type of pain is known as neuropathic pain. Multiple treatment options for pain relief range from relaxation therapy to the use of analgesic medications to deep brain stimulation. The most effective treatment option for a given individual will depend on a number of considerations, including the severity and persistence of the pain and any medical/psychological conditions.

Some individuals are born without the ability to feel pain. This very rare genetic disorder is known as congenital insensitivity to pain (or congenital analgesia). While those with congenital analgesia can detect differences in temperature and pressure, they cannot experience pain. As a result, they often suffer significant injuries. Young children have serious mouth and tongue injuries because they have bitten themselves repeatedly. Not surprisingly, individuals suffering from this disorder have much shorter life expectancies due to their injuries and secondary infections of injured sites (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2013).

The Vestibular Sense, Proprioception, and Kinesthesia

The vestibular sense contributes to our ability to maintain balance and body posture. As Figure 5.24 shows, the major sensory organs (utricle, saccule, and the three semicircular canals) of this system are located next to the cochlea in the inner ear. The vestibular organs are fluid-filled and have hair cells, similar to the ones found in the auditory system, which respond to movement of the head and gravitational forces. When these hair cells are stimulated, they send signals to the brain via the vestibular nerve. Although we may not be consciously aware of our vestibular system’s sensory information under normal circumstances, its importance is apparent when we experience motion sickness and/or dizziness related to infections of the inner ear (Khan & Chang, 2013).

These sensory systems also gather information from receptors that respond to stretch and tension in muscles, joints, skin, and tendons (Lackner & DiZio, 2005; Proske, 2006; Proske & Gandevia, 2012). Proprioceptive and kinesthetic information travels to the brain via the spinal column. Several cortical regions in addition to the cerebellum receive information from and send information to the sensory organs of the proprioceptive and kinesthetic systems.

5.5 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 5.5 The Other Sense Organs

Taste (gustation) and smell (olfaction) are chemical senses that employ receptors on the tongue and in the nose that bind directly with taste and odor molecules in order to transmit information to the brain for processing. Our ability to perceive touch, temperature, and pain is mediated by a number of receptors and free nerve endings that are distributed throughout the skin and various tissues of the body. The vestibular sense helps us maintain a sense of balance through the response of hair cells in the utricle, saccule, and semicircular canals that respond to changes in head position and gravity. Our proprioceptive and kinesthetic systems provide information about body position and body movement through receptors that detect stretch and tension in the muscles, joints, tendons, and skin of the body.

5.6 Gestalt Principles of Perception

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the figure-ground relationship

- Define Gestalt principles of grouping

- Describe how perceptual set is influenced by an individual’s characteristics and mental state

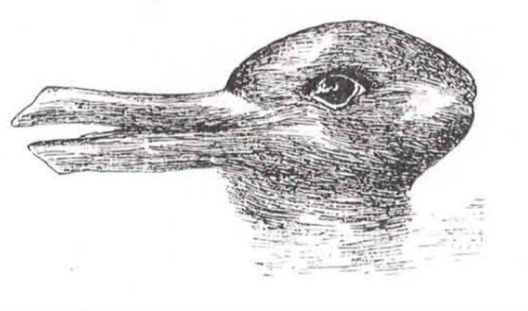

In the early part of the 20th century, Max Wertheimer published a paper demonstrating that individuals perceived motion in rapidly flickering static images—an insight that came to him as he used a child’s toy tachistoscope. Wertheimer, and his assistants Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka, who later became his partners, believed that perception involved more than simply combining sensory stimuli. This belief led to a new movement within the field of psychology known as Gestalt psychology. The word gestalt literally means form or pattern, but its use reflects the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. In other words, the brain creates a perception that is more than simply the sum of available sensory inputs, and it does so in predictable ways. Gestalt psychologists translated these predictable ways into principles by which we organize sensory information. As a result, Gestalt psychology has been extremely influential in the area of sensation and perception (Rock & Palmer, 1990).

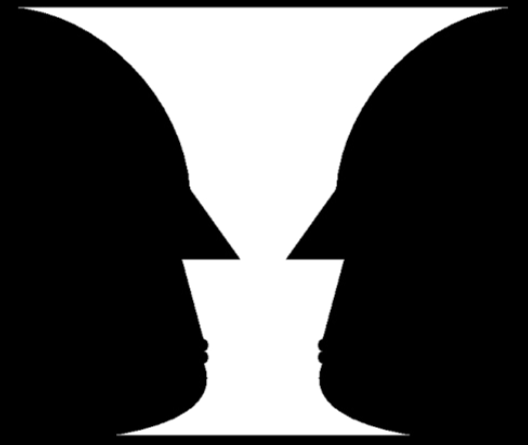

One Gestalt principle is the figure-ground relationship. According to this principle, we tend to segment our visual world into figure and ground. Figure is the object or person that is the focus of the visual field, while the ground is the background. As Figure 5.25 shows, our perception can vary tremendously, depending on what is perceived as figure and what is perceived as ground. Presumably, our ability to interpret sensory information depends on what we label as figure and what we label as ground in any particular case, although this assumption has been called into question (Peterson & Gibson, 1994; Vecera & O’Reilly, 1998).

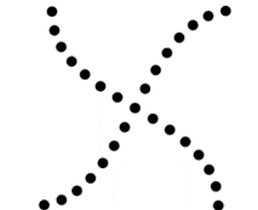

We might also use the principle of similarity to group things in our visual fields. According to this principle, things that are alike tend to be grouped together (Figure 5.27). For example, when watching a football game, we tend to group individuals based on the colors of their uniforms. When watching an offensive drive, we can get a sense of the two teams simply by grouping along this dimension.

According to Gestalt theorists, pattern perception, or our ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes, occurs by following the principles described above. You probably feel fairly certain that your perception accurately matches the real world, but this is not always the case. Our perceptions are based on perceptual hypotheses: educated guesses that we make while interpreting sensory information. These hypotheses are informed by a number of factors, including our personalities, experiences, and expectations. We use these hypotheses to generate our perceptual set. For instance, research has demonstrated that those who are given verbal priming produce a biased interpretation of complex ambiguous figures (Goolkasian & Woodbury, 2010).

5.6 TEST YOURSELF

Summary: 5.6 Gestalt Principles of Perception

Gestalt theorists have been incredibly influential in the areas of sensation and perception. Gestalt principles such as figure-ground relationship, grouping by proximity or similarity, the law of good continuation, and closure are all used to help explain how we organize sensory information. Our perceptions are not infallible, and they can be influenced by bias, prejudice, and other factors.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Not everything that is sensed is perceived. Do you think there could ever be a case where something could be perceived without being sensed?

- Please generate a novel example of how just noticeable difference can change as a function of stimulus intensity.

- Why do you think other species have such different ranges of sensitivity for both visual and auditory stimuli compared to humans?

- Why do you think humans are especially sensitive to sounds with frequencies that fall in the middle portion of the audible range?

- Compare the two theories of color perception. Are they completely different?

- Color is not a physical property of our environment. What function (if any) do you think color vision serves?

- Given what you’ve read about sound localization, from an evolutionary perspective, how does sound localization facilitate survival?

- How can temporal and place theories both be used to explain our ability to perceive the pitch of sound waves with frequencies up to 4000 Hz?

- Many people experience nausea while traveling in a car, plane, or boat. How might you explain this as a function of sensory interaction?

- If you heard someone say that they would do anything not to feel the pain associated with significant injury, how would you respond given what you’ve just read?

- Do you think a person’s sex influences the way they experience pain? Why do you think this is?

- The central tenet of Gestalt psychology is that the whole is different from the sum of its parts. What does this mean in the context of perception?

- Take a look at the following figure. How might you influence whether people see a duck or a rabbit?

Personal Application Questions

- Think about a time when you failed to notice something around you because your attention was focused elsewhere. If someone pointed it out, were you surprised that you hadn’t noticed it right away?

- If you grew up with a family pet, then you have surely noticed that they often seem to hear things that you don’t hear. Now that you’ve read this section, you probably have some insight as to why this may be. How would you explain this to a friend who never had the opportunity to take a class like this?

- Take a look at a few of your photos or personal works of art. Can you find examples of linear perspective as a potential depth cue?

- If you had to choose to lose either your vision or your hearing, which would you choose and why?

- As mentioned earlier, a food’s flavor represents an interaction of both gustatory and olfactory information. Think about the last time you were seriously congested due to a cold or the flu. What changes did you notice in the flavors of the foods that you ate during this time?

- Have you ever listened to a song on the radio and sung along only to find out later that you have been singing the wrong lyrics? Once you found the correct lyrics, did your perception of the song change?

Tips on How to Study the Material in a Sensation and Perception Chapter

In previous chapters, you learned various study techniques, such as how to create mnemonics, concept maps, and diagrams, to help you organize your reading material and prepare for exams. These strategies can also be adapted to study the content in this chapter, which a times may be dense and challenging to structure. The following four suggestions below are offered as a guide that you can use to help systematically break down and organize the material, making it easier to understand and retain for your exam.

A. Organize Key Concepts (Only some of the Key Concepts of the Chapter are found in the example below)

- Break the chapter into Sensation vs. Perception:

- Sensation → How sensory organs detect stimuli.

- Learn about sensory thresholds (absolute threshold, subliminal messages, difference threshold).

- Perception → How the brain interprets sensory information.

- Understand perceptual processing (bottom-up vs. top-down processing).

- Sensation → How sensory organs detect stimuli.

- Waves and Wavelengths

- Amplitude → The height of the wave measured from peak to trough.

- Wavelength → Measured from peak to peak

- Frequency → Related to wavelength and refers to the number of waves that pass a given point over a time. Expressed in Hz or cycles per second.

- Longer wavelengths = Lower frequency

- Shorter wavelengths = Higher frequency

B. Use Active Study Methods

- Make flashcards for key terms like “transduction,” “sensory adaptation,” and “perceptual constancy.”

- Create concept maps to connect different sensory modalities and perceptual principles.

- Explain concepts out loud in your own words or teach someone else.

C. Reinforce with Mnemonics and Memory Techniques

- Use mnemonics to remember parts of the eye (e.g., “CORnea Covers” for the cornea’s function).

- Associate key concepts with fun analogies for example; If you order a pizza and someone adds one extra shred of cheese, you probably won’t notice. But if they add an entire handful, you will! The smallest amount of change you can detect is the difference threshold (JND). Remember that if you can’t think of your own analogies, then use AI for help.

D. Practice with Application Questions

- Work on any review questions at the end of section.

- Take practice quizzes (online resources, or self-made).

Study Guide Outline: Sensation and Perception Chapter 5.

(Note: Any of the information below can be placed on flash cards or used to create a flowchart or a concept map.)

1. Sensation versus Perception

A. Definitions of Sensation and Perception

-

-

- Sensation: The physical process where sensory organs detect external stimuli (e.g., light, sound, taste).

- Perception: The psychological process of organizing, interpreting, and consciously experiencing sensory information.

-

B. The Basics of Sensation

-

-

- Transduction: Conversion of physical energy (light, sound, etc.) into electrical signals the brain can process.

- Five Traditional Senses: Vision, hearing (audition), smell (olfaction), taste (gustation), touch (somatosensation).

- Additional Senses:

- Vestibular sense (balance)

- Proprioception/Kinesthesia (body position/movement)

- Nociception (pain)

- Thermoception (temperature)

- Additional Senses:

- Thresholds:

- Absolute Threshold: Minimum stimulation needed to detect a stimulus 50% of the time.

- Example: Seeing a candle 30 miles away in the dark.

- Difference Threshold / Just Noticeable Difference (JND): The smallest difference between two stimuli that can be detected 50% of the time.

- Weber’s Law: Larger stimuli require larger differences to be noticed.

- Example: Easier to notice the weight change from 1 to 2 lbs. than 10 to 11 lbs.

- Absolute Threshold: Minimum stimulation needed to detect a stimulus 50% of the time.

-

C. The Basics of Perception

-

-

- Bottom-Up Processing: Perception driven by external sensory input.

- Example: Reading letters and forming a word.

- Top-Down Processing: Perception influenced by expectations, experience, and knowledge.

- Example: Recognizing your favorite song even if parts are missing.

- Bottom-Up Processing: Perception driven by external sensory input.

-

D. Sensory Adaptation

-

-

- Occurs when we stop noticing constant, unchanging stimuli.

- Example: Not feeling your clothes or noticing a loud radio after a while.

- Occurs when we stop noticing constant, unchanging stimuli.

-

E. Role of Attention

-

-

- Attention: Determines what sensory information is processed into perception.

- Inattentional Blindness: Failing to notice visible objects when attention is directed elsewhere.

- Example: Gorilla in the basketball video experiment.

-

F. Signal Detection Theory

-

-

- Explains how we detect signals under uncertainty or distraction.

- Influenced by motivation, experience, expectations.

- Example: A mother hearing her baby cry over other sounds.

- Influenced by motivation, experience, expectations.

- Explains how we detect signals under uncertainty or distraction.

-

G. Cultural and Personal Influences

-

-

- Culture: Affects perception (e.g., visual illusions like the Müller-Lyer illusion).

- Personality: Thrill-seeking children prefer sour tastes.

- Beliefs/Expectations: Influence perception (e.g., “reduced-fat” labels affect taste ratings).

-

2. Waves and Wavelengths

A. Overview

-

-

- Both visual and auditory stimuli occur as waves, and understanding their physical properties helps us understand how we see and hear the world.

-

B. Basic Wave Properties

-

-

- Amplitude: Height of a wave (from center line to peak or trough); linked to brightness (vision) or loudness (hearing).

- Wavelength: Distance from one peak to the next; linked to color (vision) or pitch (hearing).

- Number of waves that pass a point per second (measured in Hz); higher frequency = shorter wavelength.

-

C. Light Waves (Vision)

-

-

- Electromagnetic Spectrum: Full range of electromagnetic radiation (includes X-rays, UV, visible light, etc.)

- Visible Spectrum (Human): 380–740 nanometers (nm)

- Mnemonic: ROYGBIV (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet)

- Red = longer wavelength

- Violet = shorter wavelength

- Mnemonic: ROYGBIV (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet)

- Amplitude of Light: Affects brightness/intensity of color

- Species Differences:

- Bees can see ultraviolet

- Snakes detect infrared

-

D. Sound Waves (Hearing)

-

-

- Frequency = Pitch

- High frequency = high pitch

- Low frequency = low pitch

- Amplitude = Loudness

- Measured in decibels (dB)

- Typical Decibel Levels:

- Whisper = 30 dB

- Conversation = 60 dB

- Rock Concert = 120 dB

- Pain Threshold = 130 dB

- Typical Decibel Levels:

- Measured in decibels (dB)

- Audible Range (Humans): 20 – 20,000 Hz

- Dogs: 70–45,000 Hz

- Cats: 45–64,000 Hz

- Beluga Whales: 1,000–123,000 Hz

- Hearing Damage:

- Prolonged exposure above 80 dB can damage hearing.

- Earbuds at max volume (~100–105 dB) can cause noise-induced hearing loss in 15 minutes.

- Prolonged exposure above 80 dB can damage hearing.

- Frequency = Pitch

-

E. Timbre (Sound Quality)

-

-

- Timbre: Quality or “color” of a sound that makes it unique

- Affected by frequency, amplitude, and timing

- Explains why the same note sounds different on a piano vs. guitar

-

3. Vision

A. The Purpose of Vision

-

-

- Vision helps us navigate the physical world and interact with people and objects.

- Our brain constructs a mental representation of our environment using visual input.

-

B. Anatomy of the Eye

-

-

- Cornea: Transparent outer layer; focuses light and protects the eye.

- Pupil: Opening that lets light into the eye; size changes with light and emotions.

- Iris: Colored part; controls pupil size.

- Lens: Transparent and flexible; focuses light onto the retina.

- Retina: Light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye.

- Fovea: Small central point on retina; densely packed with cones.

- Optic Nerve: Transmits visual info from retina to brain

- Blind Spot: Area with no photoreceptors; brain “fills in” missing info.

-

C. Photoreceptors

-

-

- Cones: Concentrated in the fovea and are responsible for perceiving color and fine detail (spatial resolution)

- Rods: Responsible for perceiving dim light and movement. Do not respond to color or detail.

- Night Blindness: Difficulty seeing in low light due to poor rod function.

-

D. Pathway of Visual Processing

-

-

- 1- Light enters through cornea → pupil → lens → retina.

- 2- Photoreceptors send signals via ganglion cells → optic nerve.

- 3- Optic nerves cross at the optic chiasm:

- Right field of view → left brain

- Left field of view → right brain

- 4- Signals go to the occipital lobe for processing:

- “What” pathway: object identification

- “Where/How” pathway: spatial location and interaction

-

E. Color Vision Theories

-

-

- Trichromatic Theory: 3 types of cones for red, green, blue wavelengths; explains color at retinal level.

- Opponent-Process Theory: Colors processed in pairs: red-green, blue-yellow, black-white; explains afterimages.

- Both theories are valid, but apply at different stages of visual processing.

- Trichromatic Theory explains color processing at the foveal level.

- Opponent-Process Theory explains color at the cortical level.

-

F. Color Blindness

-

-

- Most common: Red-green color deficiency

- X-linked: More common in males.

- Total color blindness (only rods, grayscale vision) is rare.

-

G. Depth Perception

-

-

- Ability to perceive 3-D space and object location.

- Binocular Cues (Need both eyes)

- Binocular disparity: Each eye sees slightly different image; brain merges them.

- Monocular Cues (One Eye)

- Linear Perspective: Parallel lines appear to meet in the distance.

- Interposition: Closer objects block farther ones.

- Relative Size: Smaller objects are perceived as farther away.

- Horizon Position: Objects closer to the horizon are perceived as farther.

- Binocular Cues (Need both eyes)

- Ability to perceive 3-D space and object location.

-

4. Hearing

A. Introduction to Hearing

-

-

- Audition: The sense of hearing; perception of sound waves.

- Sound waves: Vibrations in the air that our ears detect and convert into electrical signals for the brain to interpret.

-

B. Anatomy of the Auditory System

-

-

- Basic Properties of Sound Waves

- Amplitude: Loudness (higher amplitude = louder sound).

- Frequency: Pitch (higher frequency = higher pitch).

- Timbre: Sound quality (e.g., natural vs. synthesized)

- Pathway of Sound

- Pinna: Funnels sound into the ear.

- Auditory Canal: Directs sound to the eardrum.

- Tympanic Membrane (Eardrum): Vibrates in response to sound.

- Ossicles: Tiny bones (malleus, incus, stapes) amplify vibrations.

- Cochlea: Fluid-filled, snail-shaped structure with auditory hair cells on the basilar membrane.

- Organized by frequency (tonotopic organization).

- Converts sound to electrical signals.

- Cochlear Nerve → Thalamus → Primary Auditory Cortex (Temporal Lobe)

- Basic Properties of Sound Waves

-

C. Pitch Perception Theories

-

-

- Temporal Theory

- Pitch = rate of neural firing.

- Works for low to moderate frequencies (<4,000 Hz).

- Limited by how fast neurons can fire.

- Place Theory

- Different parts of the basilar membrane respond to different frequencies.

- Base = high frequencies; tip = low frequencies.

- How Both Theories Work Together

- Low-mid frequencies → Temporal & Place

- High frequencies → Place only

- Sound Localization

- Monaural Cues (one ear)

- Helps detect vertical location (above/below, front/behind).

- Based on how sound interacts with the pinna.

- Binaural Cues (both ears)

- Helps detect horizontal location.

- Interaural Level Difference: Sound is louder in the ear closer to the source.

- Interaural Timing Difference: Sound reaches one ear slightly earlier.

- Helps detect horizontal location.

- Monaural Cues (one ear)

- Temporal Theory

-

D. Hearing Loss

-

-

- Conductive Hearing Loss

- Problem: Sound can’t reach cochlea.

- Causes: Blockages, damage to eardrum/ossicles, fluid buildup.

- Treatment: Hearing aids.

- Sensorineural Hearing Loss

- Problem: Damage to inner ear or nerve pathways.

- Causes: Age, noise, disease, trauma, toxins.

- Treatment: Sometimes cochlear implants (if hair cells are damaged).

- Ménière’s Disease

- Inner ear disorder → hearing loss, vertigo, tinnitus.

- May require cochlear implants.

- Conductive Hearing Loss

-

5. The Other Senses

A. Overview

-

-

- While vision and hearing are well-studied, psychology also examines chemical senses (taste and smell) and body senses (touch, temperature, pain, balance, body position).

-

B. Chemical Senses

-

-

- Taste (Gustation)

- Basic Tastes: Sweet, salty, sour, bitter, umami (savory), and fatty taste (emerging evidence).

- Taste Buds: Clusters of taste receptor cells located on the tongue, mouth, and throat.

- Lifespan: Taste buds regenerate every 10–14 days.

- Signal Path: Taste molecules bind to receptors → Neural signals → Medulla → Thalamus → Limbic System → Gustatory Cortex (between frontal and temporal lobes).

- Smell (Olfaction)

- Olfactory Receptors: Located in a mucous membrane at the top of the nose; detect odor molecules.

- Olfactory Bulb: Sends signals to the limbic system and primary olfactory cortex.

- Species Differences: Dogs have more olfactory receptor genes (~800–1200 vs. <400 in humans).

- Pheromones: Chemical messages (e.g., for mating) used by animals; controversial role in humans.

- Taste (Gustation)

-

C. Body Senses

-

-

- Touch

- Skin Receptors:

- Meissner’s Corpuscles: Pressure, low-frequency vibration

- Pacinian Corpuscles: High-frequency vibration, transient pressure

- Merkel’s Disks: Light pressure

- Ruffini Corpuscles: Skin stretch

- Free Nerve Endings:

- Thermoception: Sensing temperature

- Nociception: Sensing pain or potential harm

- Skin Receptors:

- Pain Perception

- Purpose: Warns of injury; motivates protection and healing.

- Types:

- Inflammatory Pain: Due to tissue damage

- Neuropathic Pain: Due to nerve damage; exaggerated pain signals

- Touch

-

D. Balance and Body Position

-

-

- Vestibular Sense (Balance)

- Organs: Utricle, saccule, semicircular canals (in the inner ear).

- Function: Detect head motion and gravity via hair cells in fluid-filled structures.

- Problems: Inner ear infections can cause dizziness/motion sickness.

- Proprioception and Kinesthesia

- Proprioception: Awareness of body position.

- Kinesthesia: Awareness of body movement.

- Receptors: Found in muscles, joints, tendons, and skin.

- Pathway: Information → Spinal cord → Cerebellum + multiple brain regions for coordination and control.

- Vestibular Sense (Balance)

-

6. Gestalt Principles of Perception

A. Overview of Gestalt Psychology

-

-

- Gestalt psychology is a school of thought that emerged in the early 20th century, founded by Max Wertheimer, along with Wolfgang Köhler and Kurt Koffka. It emphasizes that the whole is different from the sum of its parts—our brains interpret sensory information in predictable and organized ways.

- Perceptual Hypotheses:

- These are educated guesses our brain makes when interpreting sensory input.

- Influenced by personality, experience, and expectations.

- Can lead to biased interpretations, especially with ambiguous or unclear images.

-

B. Key Principles of Gestalt Perception

-

-

- Figure-Ground Relationship

- We perceive objects (figures) as separate from the background (ground).

- Example: A face seen in front of a wallpaper pattern.

- We perceive objects (figures) as separate from the background (ground).

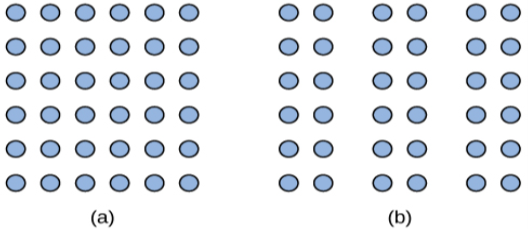

- Proximity

- Objects that are close together are perceived as a group.

- Example: Words are read correctly because letters in a word are close together.

- Objects that are close together are perceived as a group.

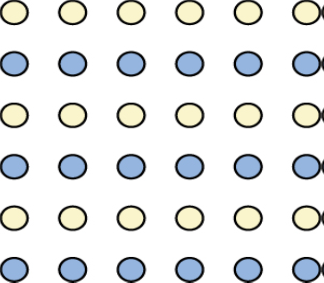

- Similarity

- Objects that are alike in color, shape, or size are grouped together.

- Example: In sports, we group players based on uniform colors.

- Objects that are alike in color, shape, or size are grouped together.

- Continuity (Law of Good Continuation)

- Humans prefer smooth, continuous patterns over jagged or broken ones.

- Example: We follow curved lines rather than abrupt angles when viewing paths.

- Humans prefer smooth, continuous patterns over jagged or broken ones.

- Closure

- We tend to fill in gaps to perceive a complete image.

- Example: A circle with missing pieces is still seen as a full circle.

- We tend to fill in gaps to perceive a complete image.

- Figure-Ground Relationship

-

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Sensation and Perception by Adam John Privitera. Licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 Deed. ↵

- Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Sensation and Perception by Adam John Privitera. Licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 Deed. ↵

- Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Sensation and Perception by Adam John Privitera. Licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 Deed. Edited by Maria Pagano ↵

- Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Sensation and Perception by Adam John Privitera. Licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 Deed. Edited by Maria Pagano ↵

- Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Sensation and Perception by Adam John Privitera. Licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 Deed. ↵

- Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Sensation and Perception by Adam John Privitera. Licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 Deed. ↵

- Noba Textbook Series: Psychology. Sensation and Perception by Adam John Privitera. Licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0 Deed. ↵

what happens when sensory information is detected by a sensory receptor

conversion from sensory stimulus energy to action potential

way that sensory information is interpreted and consciously experienced

minimum amount of stimulus energy that must be present for the stimulus to be detected 50% of the time

the smallest amount by which two sensory stimuli can differ in order for an individual to perceive them as different.

difference in stimuli required to detect a difference between the stimuli

a psychological principle that states that the smallest noticeable difference between two stimuli is proportional to the intensity of the original stimulus.

system in which perceptions are built from sensory input

interpretation of sensations is influenced by available knowledge, experiences, and thoughts

not perceiving stimuli that remain relatively constant over prolonged periods of time

ability to actively process specific information in the environment while ignoring other information.

failure to notice something that is completely visible because of a lack of attention

change in stimulus detection as a function of current mental state

height of a wave

lowest point of a wave

length of a wave from one peak to the next peak

(also, crest) highest point of a wave

number of waves that pass a given point in a given time period

portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that we can see

all the electromagnetic radiation that occurs in our environment

logarithmic unit of sound intensity

sound’s purity

transparent covering over the eye

small opening in the eye through which light passes

colored portion of the eye

curved, transparent structure that provides additional focus for light entering the eye

small indentation in the retina that contains cones

light-sensitive lining of the eye

light-detecting cell

specialized photoreceptors that works best in bright light conditions and detects color

specialized photoreceptor that works well in low light conditions

carries visual information from the retina to the brain

point where we cannot respond to visual information in that portion of the visual field

X-shaped structure that sits just below the brain’s ventral surface; represents the merging of the optic nerves from the two eyes and the separation of information from the two sides of the visual field to the opposite side of the brain

color vision is mediated by the activity across the three groups of cones

color is coded in opponent pairs: black-white, yellow-blue, and red-green

continuation of a visual sensation after removal of the stimulus

ability to perceive depth

cues that relies on the use of both eyes

slightly different view of the world that each eye receives

cue that requires only one eye

perceive depth in an image when two parallel lines seem to converge

The physical stimulus for audition which results from changes in air pressure.

Ability to process auditory stimuli. Also called hearing.

perception of a sound’s frequency

visible part of the ear that protrudes from the head

Tube running from the outer ear to the middle ear.

eardrum

middle ear ossicle; also known as the hammer

middle ear ossicle; also known as the anvil

middle ear ossicle; also known as the stirrup

fluid-filled, snail-shaped structure that contains the sensory receptor cells of the auditory system

Receptors in the cochlea that transduce sound into electrical potentials.

thin strip of tissue within the cochlea that contains the hair cells which serve as the sensory receptors for the auditory system

The arrangement of auditory neurons in the brain that process sounds of different frequencies. Also known as "place coding" or "frequency coding".

A sensory nerve that carries auditory information from the inner ear to the brain. Also known as the auditory nerve or acoustic nerve.

Carries sensory information related to spatial sensation, posture, and hearing, making it vulnerable to various pathological conditions

Area of the cortex involved in processing auditory stimuli.

sound’s frequency is coded by the activity level of a sensory neuron

different portions of the basilar membrane are sensitive to sounds of different frequencies

one-eared cue to localize sound

two-eared cues to localize sound

partial or complete inability to hear

deafness from birth

failure in the vibration of the eardrum and/or movement of the ossicles

failure to transmit neural signals from the cochlea to the brain

results in a degeneration of inner ear structures that can lead to hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, and an increase in pressure within the inner ear

taste for monosodium glutamate

groupings of taste receptor cells with hair-like extensions that protrude into the central pore of the taste bud

sensory cell for the olfactory system

bulb-like structure at the tip of the frontal lobe, where the olfactory nerves begin

chemical message sent by another individual

touch receptor that responds to pressure and lower frequency vibrations

touch receptor that detects transient pressure and higher frequency vibrations

touch receptor that responds to light touch

touch receptors that detects stretch

temperature perception

sensory signal indicating potential harm and maybe pain

pain from damage to neurons of either the peripheral or central nervous system

genetic disorder that results in the inability to experience pain

contributes to our ability to maintain balance and body posture

perception of body position

perception of the body’s movement through space

field of psychology based on the idea that the whole is different from the sum of its parts

segmenting our visual world into figure and ground

things that are close to one another tend to be grouped together

things that are alike tend to be grouped together

(also, continuity) we are more likely to perceive continuous, smooth flowing lines rather than jagged, broken lines

organizing our perceptions into complete objects rather than as a series of parts

ability to discriminate among different figures and shapes

educated guesses used to interpret sensory information