7 Spacetime: nomadism and sedentarity

“Britain ruled from the sea, without land conquest, by blockade and fleet.”

“The enemy becomes invisible, elusive, no longer a clear and present danger.”

Land and Sea: A World-Historical Meditation, Carl Schmitt, 1942

The concept of territoriality underpins the workings of the modern state. The sovereignty of the state is articulated in spatial terms in its relation to the population and to other states. Internally, the state claims the monopoly over the use of violence within an analytically demarcated space. Externally, at least in theory, state’s are forbidden from interfering with its each other’s domestic politics. This conception—however powerful its influence on the state’s self-understanding and on scholar’s characterizations of political regimes—is problematic in several interrelated respects.

On the one hand, it’s rooted in sedentary political regimes where agricultural production is the main determinant in state’s ability to extract economic resources from the population. It is an abstraction made from within a specific material context. The sedentarism of the modern state operates on the basis of a framework that marginalizes, if not fully excluding, nomadism from the center of political theory. Not only is nomadism a well-documented historical phenomenon challenging centrality of sedentarism to political theory, the latter is also a land-based political theory with a predilection for conquest and stasis instead of the open-ended movement of nomads that bring forth a spacetime irreducible to permanent demarcation of political space (Isenberg, 2000). Sedentarist point of view is inadequate also for the task of accounting for the dominant mode of operation of maritime political regimes, e.g., the major colonialist forces such as the British empire. The priority of movement in nomadism and in sea-based politics/warfare call for a different set of conceptual instruments to account for these intrinsically dynamic realities.

“Nomads do not precede the sedentaries; rather, nomadism is a movement, a becoming that affects sedentaries, just as sedentarization is a stoppage that settles the nomads. Griaznov has shown in this connection that the most ancient nomadism can be accurately attributed only to populations that abandoned their semi urban sedentarity, or their primitive itineration, to set off nomadizing. It is under these conditions that the nomads invented the war machine, as that which occupies or fills nomad space and opposes towns and States, which its tendency is to abolish.” 7000 B.C. Apparatus of Capture (P. 470), Deleuze & Guattari

The dawn of the modern political system from the 15th century onwards was the result not only of the gradual consolidation of power by absolutist states in Europe. Indeed, the centuries-long push by Turkic and Mongolian nomadic empires (Chambers, 1979; Derrida, 2009) and the saturation of trade-routes leading to a trade-deficit in the West paved the ground for the colonization of the Americas and Africa, campaigns that first emerged as attempts to find alternate trade routes to Asia that would bypass Ottoman Empire‘s hegemony in the Mediterranean sea.

At the beginning of the 20th century, European powers entered into a colonialist arms race. Virilio describes the process whereby visual arts and the instruments of logistics began feeding each other, leading to the symbiotic proliferation of cinema and war, which reached a climax in the assemblage of satellite vision, instant telecommunication, and ballistic missiles. Space as something that stands against the political will is almost completely absorbed into the political machinery which overcomes its own inward looking development (e.g., as in walled-cities) by distributing itself in space as dynamic networks.

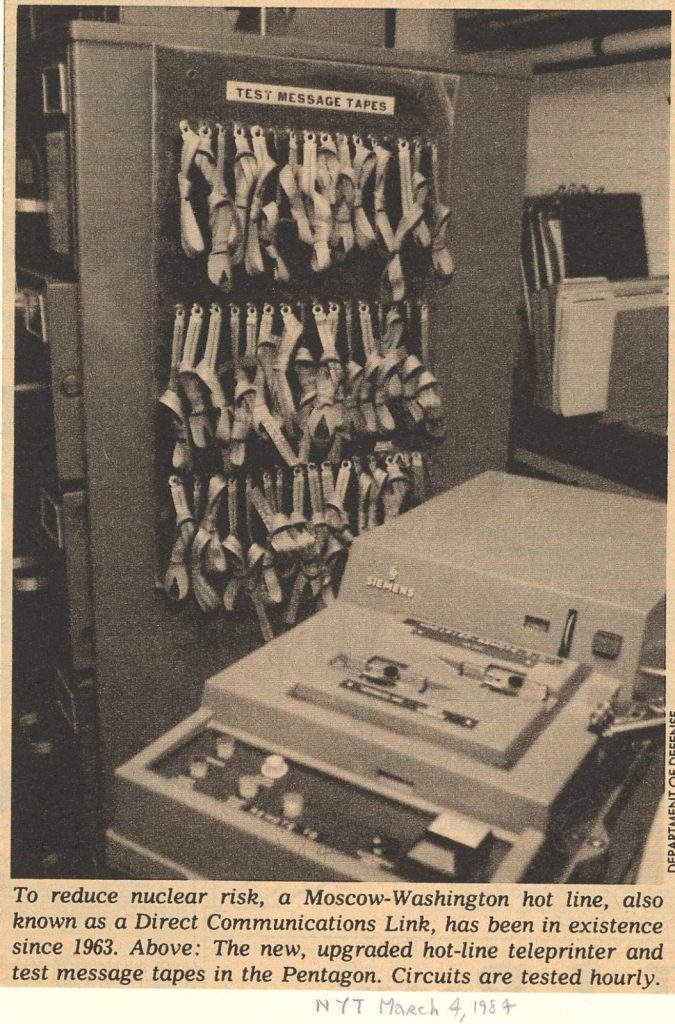

In this conjecture, the differential of speed increasingly becomes the foremost political category determining the capacity of one force to influence another. Modern information systems and the supercomputers on which they depend emerged through the pursuit of national security imperatives—such as protecting the integrity of distant communications and opening up new fronts of counter-insurgency warfare—during the agonistic political/military context of World War II (1991, de Landa). Computerization and embryonic forms of digitalization first kicked off with the military purpose of decoding Japanese machines of encryption by the US and UK in the early 20th century.

Communication technologies did not develop in a political vacuum devoid of strategic pressure. They are not products of ‘civil society’. Modern algorithms are rooted in World War II efforts to counter the intractable movement of German submarines that dominated the Atlantic Ocean, thereby rendering allied defense close to impossible. In this conjunction of material conditions and strategic exigencies, the speed of the corporeal movement of submarines coalesced with the speed of encryption and decryption—in a concrete fusion of informatics and force—leading to the emergence of the computer revolution.

Thus, not as memory of some by-gone era of pastoral nomadism but as a core political model, the nomadic war-machine and its construction/navigation of political spacetime requires students of political sociology to limit state/civil society-centric analysis and relate this dyad to exteriorities which are at time symbiotic and at times dissonant to its operation. Recent generalizations of algorithmic intelligence/power demands a profound rethinking of spacetime in political theory. With the decentering of the interiority of the nation-state, there is a tendency to conceptualize new forms of sociality in retro-terms, e.g., neo-feudalism, neo-fascism. In the following chapters we will explore the growing potential of networks over against the traditional territoriality of the state in order to account for these new political realities. Deleuze and Guattari named their book A Thousand Plateaus in order to draw attention to simultaneous shrinking/expansion of space that Heidegger conceptualized as the appearance of the gigantic where quantitative shifts are grasped also as qualitative shifts given their age-defining ramifications.

“A sign of this event is that everywhere and in the most varied forms and disguises the gigantic is making its appearance. In so doing, it evidences itself simultaneously in the tendency toward the increasingly small. We have only to think of numbers in atomic physics. The gigantic presses forward in a form that actually seems to make it disappear-in the annihilation of great distances by the airplane, in the setting before us of foreign and remote worlds in their everydayness, which is produced at random through radio by a flick of the hand. Yet we think too superficially if we suppose that the gigantic is only the endlessly extended emptiness of the purely quantitative. We think too little if we find that the gigantic, in the form of continual not ever-having-been-here-yet, originates only in a blind mania for exaggerating and excelling. We do not think at all if we believe we have explained this phenomenon of the gigantic with the catchword “Americanism”” (Heidegger, 1977, p. 135)

For Luciana Parisi, transformation of spatiotemporality radically alter the character of desire and reproduction of life across scales where continous transfer replaces as the paradigm of conclusivity.

“The speeding up of information trading, not only across sexes, but also across species and between humans and machines, exposes the traits of a non-climactic (non-discharging) desire spreading through a matrix of connections that feed off each other without an ultimate apex of satisfaction.” (Parisi, 2004, p. 4)

With these conceptualizations, we are far removed from master narratives that rely upon the binaries of country/city, organic/inorganic and human/nonhuman without these being reduced mere epistemological blurs as the stakes are often quite high when they function to demarcate the field of politics. With datafication populations and their living standards are perhaps more than ever segmented and placed in dynamic hierarchies and identity-categories that ossify for short periods of time into rigid hierarchies. The concepts of deterritorialization and reterritorialization (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987) are useful to describe this constant uprooting and transplantation as its side-effect. Yet perhaps they are also inadequate modes of attending to new political realities as they are stuck within the polarities of territory. New conceptualizations of speed that salvage the concept from a reduction to mechanical motion in space and link it with movement in time may arguably offer the most fertile grounds for political theorization (Virilio, 1997/2006, 2010; Clough, 2000, p. 135; Işsevenler, 2022, p. 85).

Resonating with these two modalities (nomadism and maritime power, which shares a commonality with aerial power in terms of operating in dynamic space)—which are simultaneous with and complementary to sedentary statehood, without being irreducible to its logics—the development/arrival of new technological topologies express a profound transformation of fields of political thinking towards the analytics of movement and speed, and, thereby, a relativization of the territorial basis of political power and the territorial focus of sociopolitical theory.

This relativity should be developed from multiple vantage points without presupposing translatability—but without presupposing absence of information loss/gain in moving across of these perspectives. Relativity implies a deconstruction of self-same unity of events. From the perspective of the land-based state, a resistance to settlement can emerge on the axis of capture/escape. Yet this state-centric reading does not exhaust the intelligibility of the dynamic relation from the perspective of nomadism. Schematically, the hold of territorial sovereignty over nomadism is linked to strategies of surplus accumulation. The state seeks to fix the movement of nomads and to be able to locate them in order to tax their economic activity and recruit their human resources towards its war-making efforts (Lindner, 1983). In this interest in the boundless accumulation of surplus, sedentarism tends towards the conservation of resources over the discharge of energy, the stability of organization over its rhythmic movement.

This fundamentally bureaucratic attitude of the state manifests in relation to the population across the board—not just in its archaic relationship to nomadic tribes. The first move of the state is to ask for identification; and if this is not possible, it strives to create the conditions of possibility of controllable indentities by registers, charts, and archives. This is in contrast to the essential mobility of the nomadic life-style, which is not tied to the land in the same way. Despite this essential difference in modes of life, nomads must not be disqualified from strategies of calculation and inscription. Deleuze and Guattari’s chapter on the Nomadic War-machine in A Thousand Plateaus (1980/1987) is seminal in the comparative analysis of nomadism:

“Tens, hundreds, thousands, myriads: all armies retain these decimal groupings, to the point that each time they are encountered it is safe to assume the presence of a military organization. Is this not the way an army deterritorializes its soldiers? … For so peculiar an idea-the numerical organization of people-came from the nomads. It was Hyksos, conquering nomads, who brought it to Egypt; and when Moses applied it to his people in exodus, it was on the advice of his nomad father-in-law, Jethro the Kenite, and was done in such a way as to constitute a war-machine, the elements of which are described in the biblical book of Numbers. The nomos is fundamentally numerical, arithmetic. When Greek geometrism is contrasted with Indo-Arab arithmetism,, it becomes clear that the latter implies a nomos opposable to the logos: not that the nomads “do” arithmetic or algebra, but because arithmetic and algebra arise in a strongly nomad influenced world.” (P. 388)

Here, the distinction in the political operationalization of quantification lies in the dominant interest out of which it emerges. While in sedentarism, measure is geared towards the anticipation, capture, and stabilization of movement—as in the calculation of the exact time when the river Nile flooded in the Egyptian water-based civilization—in nomadism and in the nomadic war-machine, numbering is an emergent quality of forces in movement. As Deleuze and Guattari put it: “It is a directional number, not a dimensional or metric one.” (P. 390)

“History has always dismissed nomads. Attempts have been made to apply a properly military category to the war machine (that of “military democracy”) and a properly sedentary category to nomadism (that of “feudalism”). But these two hypotheses presuppose a territorial principle: either that an imperial State appropriates the war machine, distributing land to warriors as a benefit of their position (cleric and false fiefs) or that property, once it has become private, it itself posits relations of dependence among the property owners constituting the army (true fiefs and vassalage). It both cases, the number is subordinated to an “immobile” fiscal organization, in order to establish which land can be or has been ceded, as well as to set the taxes owed by the beneficiaries themselves.” (p. 394)

The sedentarist mode of living has an embedded interest in turning the relation of land to a machinery of wealth-accumulation. While it would be unjustified to see nomadic societies as without excess and surplus, in agrarian societies there is an interest in reservation and conservation. Put figuratively, nomadic society wants to be “light,” and sedentary society “heavy”. The former supports movement and speed, the latter gravity and centralization. This propensity towards mobility renders nomadic tribes open to religious and ethnic heterogeneity, in contrast to the increasingly purist conceptions of community and tribal-lineage in land-based aristocracies.

It is possible to observe nomadic and sedentary modalities in modern political space where codified demarcations conducted either by governments or corporations are overrun by flows of intensity that feeds off of such centers of accumulation as the evolution of digital spacetime towards monopolies demonstrate. Different than other sociological oppositions such as mainstream culture and subculture, center and periphery, dominant class and oppressed class, here, the irreducibility and dependency operates without definite hierarchy among these two modalities. One can make the case for the freedom and speed enjoyed by nomadic movements versus accumulation and control enjoyed by sedentary structures. The very terms chosen to formalize this relationship can express the choice of the author or interpreter. With the miniaturization and concentration of social space and corresponding acceleration and fragmentation time, there emerges ever new possibilities of exchanges, alliances, conjunctions and alignments between terms that previously stood far apart.

“We learn that the young Osman liked to hunt in remote areas. A certain Köse Mihal, the Christian lord of Harman Kaya, always accompanied him. Our sources calls Köse Mihal a ghazi and states that “Most of these ghazis’ attendants were Christians from Harman Kaya.” It is important to note that Köse Mihal did become a Muslim, but much later. Here we must conclude that if Mihal had really been a ghazi, the term must have been a label in no sense describing the character and behavior of a Muslim Holy Warrior. While Mihal is perhaps the most famous ” Christian ghazi” his story is only the most dramatic example of Ottoman-Byzantine cooperation in the early days: dramatic because it is ultimately a story of military cooperation.” (Lindner, 1983, p. 5)

Works Cited

Bachelard, G. (1988). Air and dreams: An essay on the imagination of movement (E. R. Farrell & C. F. Farrell, Trans.). Dallas Institute Publications.

Chambers, J. (1979). The Devil’s Horsemen: The Mongol Invasion of Europe. Phoenix Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia (B. Massumi, Trans.). University of Minnesota Press. (Original work published 1980)

Heidegger, M. (1977). The question concerning technology and other essays (W. Lovitt, Trans.). Harper & Row. (Original work published 1954)

Isenberg, A. C. (2000). The destruction of the bison: An environmental history, 1750–1920. Cambridge University Press.

İşsevenler, T. (2021, December 28). After Repose. House of Time. Retrieved from https://house-of-time.org/After-Repose

Khazanov, A. M. (1994). Nomads and the outside world (2nd ed., J. Crookenden, Trans.). University of Wisconsin Press. (Original work published 1983)

Lindner, R. P. (1983). Nomads and Ottomans in Medieval Anatolia. Sinor research Institute for Inner Asian Studies.

Parisi, L. (2004). Abstract sex: Philosophy, biotechnology and the mutations of desire. Continuum.

Schmitt, C. (2015). Land and sea: A world-historical meditation (S. G. Zeitlin, Trans.; R. A. Berman & S. G. Zeitlin, Eds.). Telos Press Publishing. (Original work published 1942)

Virilio, P. (1977/2006). Speed and politics: An essay on dromology (M. Polizzotti, Trans.). Semiotext(e).

Virilio, P. (1977/2006). Speed and politics: An essay on dromology (M. Polizzotti, Trans.). Semiotext(e).

Virilio, P. (2012). The great accelerator (J. Rose, Trans.). Polity Press. (Original work published 2010)

Young, J. (2004). Heidegger’s philosophy of art. Cambridge University Press.

Media Attributions

- British submarine1 © N.Y. Public Library Picture Collection.

- Kül Tigin’s memorial

- Naval Blockage © British Museum. N.Y. Public Library Picture Collection.

- Medieval Naval Battle Scene

- Satellite repair by astronauts © Taken from Space shuttle : the first 20 years. Eds. Tony Reichhard. New York. DK Publishing. c2002 Smithsonian Institution.

- Model of Sputnik

- Mobile Hospitals

- Naval Vessel of Germany, 1st World War

- Hot line

- Nuclear missiles in a submarine

- Anglo-Soviet Treaty in 1942