Chapter 8: Circadian Rhythms and Sleep

8.7: Sleep disorders

Insomnia

Almost everyone has experienced difficulty sleeping at some point in their lives, often as a result of stress or anxiety. For example, it might be difficult to fall asleep the night before a big interview, or you may wake periodically in the hours before an important early morning flight. There is no strict definition for insomnia. The major clinical symptoms are self-reported measures, such as a dissatisfaction with nightly sleep or a change in daytime behavior, such as sleepiness, difficulty concentrating, or altered mood states. The lack of clear diagnostic criteria makes estimating prevalence difficult, but some guesses put the number of people with insomnia close to one third of the US population.

Common triggers for insomnia include heightened anxiety, stress, or advanced age. It may also be downstream of other diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, depression, or chronic pain conditions. Lifestyle can also be a major risk factor for insomnia, as jet lag and working late-night shifts can disrupt sleep patterns.

We can describe insomnia as acting at two stages. Onset insomnia is defined as a difficulty with initially falling asleep. People with onset insomnia will frequently lie in bed for a long time before finally drifting off. Maintenance insomnia, however, is a difficulty with remaining asleep. People with maintenance insomnia experience many waking events throughout the middle of the night, or they may wake up very early in the morning and be unable to get back to sleep. The two are not exclusive, and people may experience both forms of insomnia in a single night.

The most effective treatments for insomnia begin at the level of behavioral changes. Improving sleep habits, such as minimizing arousal states before bedtime, developing a reliable pattern of sleep-wake timing, eliminating caffeine intake in the afternoon and evening, and increasing daytime physical activity can decrease insomnia. Prescription medications are less preferred for insomnia treatment, since these drugs are more effective at inducing unconsciousness rather than biological sleep. These drugs can also have adverse psychological side effects such as mood swings and depression, and those adverse effects may be more severe than insomnia itself. Prolonged use of prescription sleep medications can lead to a “rebound effect,” causing a person to experience even worse insomnia when they are unable to get sleep drugs. This is called iatrogenic insomnia, and can lead to a cycle of dependence.

Clinical connection: Fatal familial insomnia

While many cases of sleeplessness last a day or two, and some cases are clinically significant and treatable with behavioral changes, a very small fraction of cases of insomnia are incurable and deadly. In people with fatal familial insomnia (FFI), they experience severe insomnia. Some patients stay awake for up to six months at a time. As a result of either the disease or the sleep deprivation, they experience altered mood states, hallucinations, dementia, and eventually death, usually within two years after a diagnosis is made.

The cause of FFI is unknown. There is a strong genetic component associated with it, as it appears frequently within certain family trees. But, there have also been a few cases of sporadic FFI, people with no apparent family members with the disease. One observation in common among people with FFI is significant damage to the thalamus, as a result of misshapen proteins called prions, a similar disease-causing agent that is responsible for mad cow disease.

Sleep apnea

Sleep apnea is characterized by nightly sleep that is frequently interrupted by the inability to breathe (a- meaning none, and pneu referring to wind, air, or breath, as in pneumonia or pneumatic pump). In turn, this lowers blood oxygen levels, causing the brain to wake the person in panic. Each wake event may only last a few seconds, but these disruptions are significant enough to prevent a person from getting the appropriate amount of restorative deep sleep. A person with sleep apnea may wake 30 times an hour, despite having no recollection of waking. The immediate result of sleep apnea is excessive daytime sleepiness, but over long periods of time, sleep apnea contributes to the development of heart disease and an increased risk for stroke.

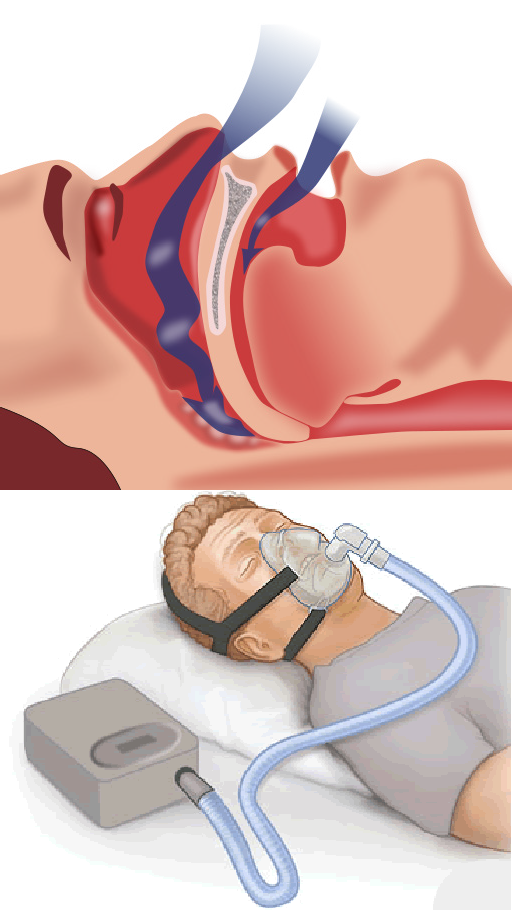

There are two forms of sleep apnea, both of which may be seen in a person with this sleep disorder. Obstructive sleep apnea is the more common of the two. This happens when soft tissue in the back of the throat temporarily collapses, which can decrease or completely block airflow into the lungs. On the other hand, central sleep apnea is mediated by some biological change in the brain that results in a decrease in involuntary breathing patterns at night, possibly due to some damage in the respiratory centers of the brain. There are several risk factors that contribute to sleep apnea, which are often a combination of genetic and environmental influences. Obesity is a major risk factor, resulting in increased soft tissue mass around the neck and torso, which can increase the likelihood of airway blockage. Advanced age contributes to sleep apnea, as the muscles that keep the airway open weaken and lose tone over time. Exposure to chemical irritants, such as cigarette smoke, contribute to inflammation and increased water retention in the soft tissue, both of which can decrease the size of the airway.

Sleep apnea is most often treated with a portable machine called a continuous positive airway pressure device, or a CPAP device. These machines are basically air pumps that connect to a mask that is worn over the nose and mouth. When used correctly, the CPAP forcibly pushes air into the person’s respiratory system, acting as an external lung. However, the CPAP can be loud and bulky, and the mask must be airtight for the treatment to be effective, making the treatment very uncomfortable. Because of this, CPAPs can cause more difficulty with sleep compared to sleep apnea itself, so they often have a low compliance rate.

Narcolepsy

Unlike the previous two sleep disorders, which result in a deficit of sleep, narcolepsy can be thought of as an “excess” of sleep. More accurately, narcolepsy is inappropriate sleep, and it manifests as frequent sleep attacks throughout the day, each event lasting for seconds or minutes at a time. An estimated 1 in 2000 people experience narcolepsy.

One of the life-threatening symptoms that appears in narcolepsy is cataplexy, which is the sudden weakening of muscle tone that accompanies a sleep attack. A cataplectic attack may cause someone to physically fall over during a narcoleptic incident. Cataplexy often happens during high emotional states, such as excitement. As with other sleep disorders, changes in lifestyle can improve the course of narcolepsy. Introducing short daily naps can be helpful, as can general good sleep habits (minimal digital device usage before sleep, going to bed and waking up at the same time everyday and engaging in physical activity regularly but not too close to bedtime). Drugs such as amphetamines (Modafinil) can be used in the daytime to stimulate activity in the CNS, and can be prescribed to treat severe cases of narcolepsy. Some antidepressant drugs can be used to treat cataplexy.

The exact cause of narcolepsy has not yet been identified. However, there are many clues that point to a dysregulation of the signaling molecule orexin produced by cells in the lateral hypothalamus. These neurons die off in people with narcolepsy, but the cause of why the neurons die is unknown. Also, having a genetic predisposition to narcolepsy does not guarantee that a person will experience the symptoms, indicating that there is some combination of genetic and environmental factors that lead to narcolepsy.

Clinical connection: REM sleep behavior disorder.

One very rare parasomnia (sleep disorder) called REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) can cause people to carry out complex, highly coordinated motor actions while they are sleeping, sometimes acting out their dreams as if they were reality. People with RBD are at risk of injuring themselves or others.Their sleep actions may be in response to a violent nightmare, causing them to jump out of bed, kick or punch the air, run through the house, or throw things. Perhaps, one of the most shocking instances of parasomnia-induced sleepwalking was the 1987 case of Kenneth James Parks, a Canadian man who, in his sleep, drove 23 km to the house of his in-laws and stabbed both of them with a kitchen knife. After his arrest, scientists discovered that his brain activity was highly abnormal during sleep. As a result of the medical examination, the Supreme Court of Canada acquitted him of murder in 1992.

Restless legs syndrome

A person with restless legs syndrome (RLS) experiences frequent unusual sensations in their limbs, such as a tingling or buzzing. Because these uncomfortable sensations disappear with movement, people with RLS often want to move their legs around. Technically, RLS is not exclusively a sleep disorder, since patients experience similar symptoms when they are simply at rest, while sitting and watching TV or studying. But, the sensation happens frequently as a person is lying down in bed, thus delaying the onset of sleep. RLS is likely underdiagnosed, since it is a disease that exists on a spectrum. Those who are minimally affected probably do not experience significant changes in sleep. Estimates of prevalence of RLS range from 2.5% to 15%. Major risk factors for RLS are iron deficiency and dopamine dysregulation. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but it does have some genetic component

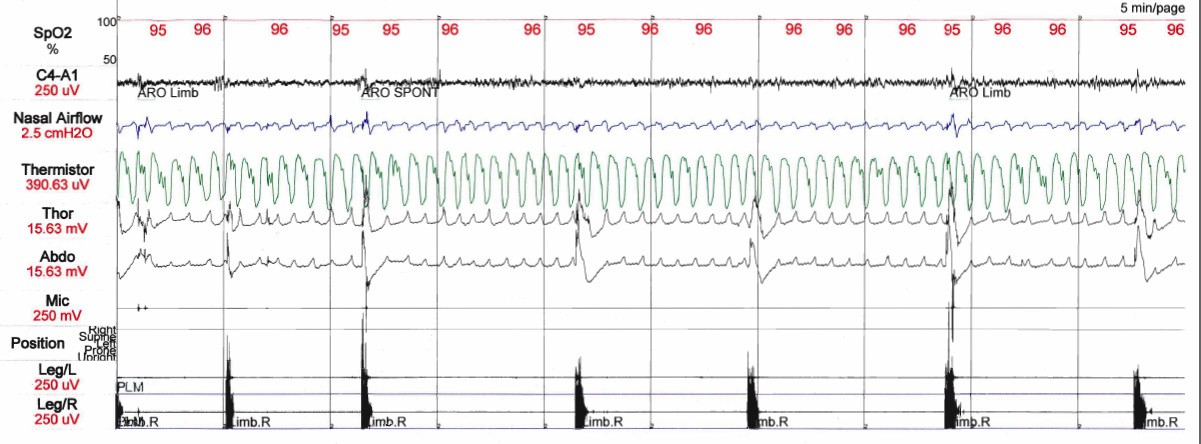

Periodic limb movement disorder

Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is a motor disorder that causes abrupt limb movement such as kicking, flexing, or jerking. Usually, the limb movement is in the legs, but arm movement can also be seen. Since motor activity is actively suppressed during REM sleep, limb movement is most often seen in the first half of sleep when NREM sleep dominates the sleep cycle. Each series of limb activity repeats at about a 30 second interval. PLMD is different from RLS, since PLMD results in involuntary movements that a person may not be aware of, while RLS related-movement is voluntary. As a movement disorder, the course of PLMD can be modified by dopaminergic drugs. Alternatively, sedatives can help minimize nighttime movement.