Chapter 11: Emotion and Affective Neuroscience

11.2 Theories of Emotion

Austin Lim, Ph.D. and Helena Ledmyr, PhD, INCF (Editor)

In the 1880s, psychologist William James and physician Carl Lange independently developed a new theory about the origin of emotion. According to the James-Lange theory of emotion, the body’s physiological changes come before the onset of an emotional response. For example, imagine encountering a hungry lion on the sidewalk. The James-Lange theory tells us that the perception of the threat of being eaten causes the sympathetic nervous system fight-or-flight” response (elevated heart rate and blood pressure, increased respiration, and cellular mobilization of energy), and that these physiological changes trigger the onset of fear.

Soon after, in the 1920s and 30s, two physiologists named Walter Cannon and his doctoral student Philip Bard criticized the James-Lange theory. In one experiment, they surgically removed the entire sympathetic nervous system from cats, destroying the nerves that regulate vascular dilation, the activity of liver enzymes, and the reaction that causes the hair standing on end. These cats were then put before a threatening aggressor. If the James-Lange theory was true, then the physiological changes should precede the emotive response. However, the cats exhibited fear/aggression (such as posturing, hissing, and clawing) even without an intact sympathetic nervous system. Relatedly, patients with spinal cord injuries have a similar lack of autonomic inputs to the brain, but their capacity for emotional responding is still intact.

In a second criticism, Cannon and Bard proposed that the physiological changes seen in sympathetic nervous system activity may arise for a variety of reasons, not always for emotionally salient reasons. For example, intense exercise causes strong cardiorespiratory changes; however, we do not necessarily feel a strong emotional state after this physiological perturbation. Likewise, exogenous administration of epinephrine, onset of fever, or being in cold temperatures may also trigger some physiological changes without causing a strong emotional response.

Based on their evidence opposing the James-Lange theory, Cannon and Bard developed an alternative explanation for the origin of emotions. According to the Cannon-Bard theory of emotion, the perception of an emotionally charged stimulus prompts simultaneous but independent activation of both the autonomic nervous system and the emotional response.

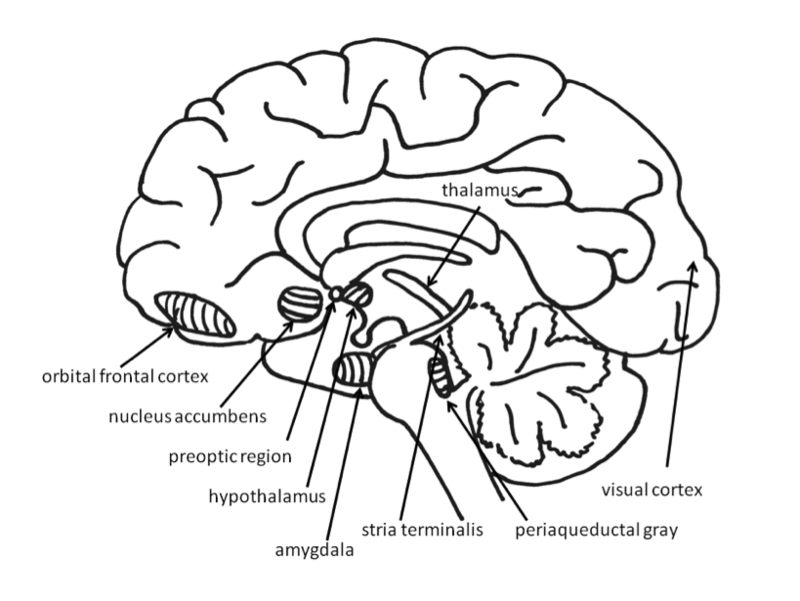

The Cannon-Bard theory also draws attention to the neuroanatomical structures that trigger the autonomic and emotional responses, with a particular focus on diencephalon structures such as hypothalamus and thalamus. To localize the anatomy behind emotional signaling, researchers performed a series of lesion experiments, systematically injuring different parts of the brain. To their surprise, when the cortex of the cat was surgically separated from the rest of the nervous system, a procedure called the decorticate preparation, the cats would exhibit a hyper-aggressive response to stimuli. For example, an innocuous touch of the tail would trigger violent clawing, biting, and hissing, behaviors which were described as sham rage. However, when they lesioned the thalamus, sham rage was no longer observed. They concluded that rage (and other powerful emotions) is normally under inhibitory control by the cortex.

Just a few years later, in 1937, American neuroanatomist James Papez (pronounced payps) ascribed emotional behavior to a particular series of brain structures. These structures, collectively called the Papez circuit, consist of the hypothalamus, cingulate gyrus, thalamus, and hippocampus. Papez observed unusual aggression among animals with injury to these structures, suggesting that emotional responding is distributed across many areas, rather than localized. Paul MacLean later revised the Papez circuit to include the amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, and some part of the basal ganglia, and renamed the circuit — the limbic system (see Figure 11.5).

In 1939, two researchers named Heinrich Kluver and Paul Bucy described a unique set of emotional deficits in monkeys after removing both their temporal lobes, which contain both the amygdala and the hippocampal structures, as well as association visual areas. These animals fail to display fear or anger, even in the face of life-threatening stimuli such as a large snake. They also display visual agnosia (the inability to recognize faces or objects visually), psychic blindness, hypersexuality, and hyperorality (an inappropriate fixation with using the mouth to interact with surroundings, such as licking or eating nonfoods). Collectively, these sets of symptoms are called Kluver-Bucy syndrome.

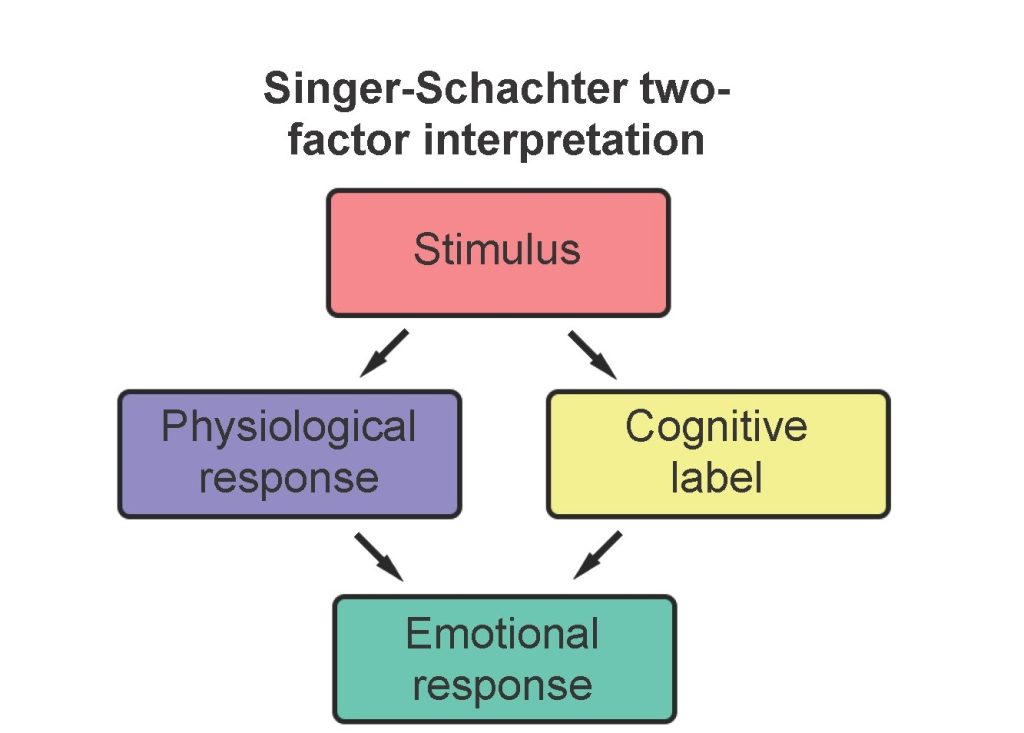

A new angle to the origin of emotion was proposed by Stanley Schachter and Jerome E. Singer in 1962. They were interested in how the same physiological response can be attached to two wildly different emotions – consider the rise in heart rate and respiration that are associated with encountering that lion (fear), or when you receive wonderful news (elation), or when you make eye contact with your romantic partner (love). According to their two-factor theory of emotion, people use a combination of the physiological response and a cognitive label to determine the emotion that is most appropriate for a given circumstance. The cognitive label comes from two parts. One is prior knowledge, such as the thought processes “lions eat meat if they are hungry, so I should be afraid.” The other part is observing environmental cues, such as “everyone around me is running away and screaming, so I should also be afraid.”

To test their theory, Schachter and Singer administered epinephrine to patients. Epinephrine is a hormone that produces the physiological signs very similar to those observed in a sympathetic nervous system response: elevation of heart rate, respiration, blood flow to muscles, and energy utilization. Then, the patient is put into a waiting room with another “patient”- in actuality an undercover member of the

research team (the confederate). For one set of patients, the confederate would act “euphorically,” jokingly playing trash-can basketball, making paper airplanes, and hula-hooping, all the while exclaiming how much fun they are having, inviting the patient to play along. For another set of patients, the confederate would act in anger, expressing irritation before eventually ripping up the survey and storming out of the study.

When the patients were not told what to expect from the epinephrine, they were more sensitive to the emotional responses of the confederate. This demonstrated that environmental cues play a significant role in determining emotion regardless of physiological state.