Chapter 1: Introduction to Biological Psychology

1.1: Introduction

Michael J. Hove and Steven A. Martinez

As you start reading, take a couple of deep breaths. Breathing typically happens automatically and without your awareness, but you can easily control your body to take a deep breath. Now point your attention to your expanding chest, the feeling of air flowing past your lips, and the sound of your deep breath. After a few mindful breaths, you might feel more “in your body” or relaxed. After a few months of regularly attending to your breath (as is done in many meditation practices), you might notice increased attentional control, emotion regulation, and self-awareness, and actually change the physical structure of your brain (Tang et al., 2015).

This is all kind of strange and leads to questions such as:

- How can some bodily functions be maintained automatically without awareness, but can also be controlled under your volition?

- Why are we typically unaware of sensations that are constant, but we can direct our attention to consciously perceive them?

- Why do we even have subjective experience? (or from an evolutionary perspective, did having subjective experience help humans survive and pass on their genes?)

- Who, what, and where is the “self” who experienced this? (There are no little characters pulling levers in your head like in the Disney movie Inside Out.)

- How can awareness of a few deep breaths change your emotional state?

- How can regularly performing an activity change the structure of your brain?

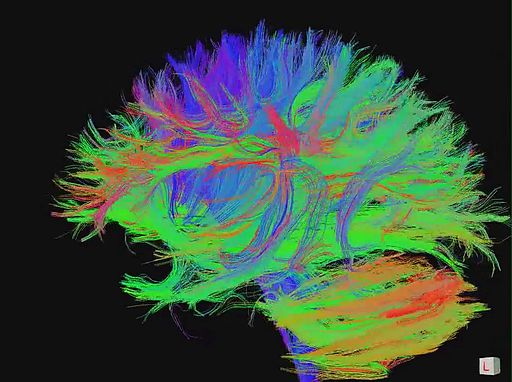

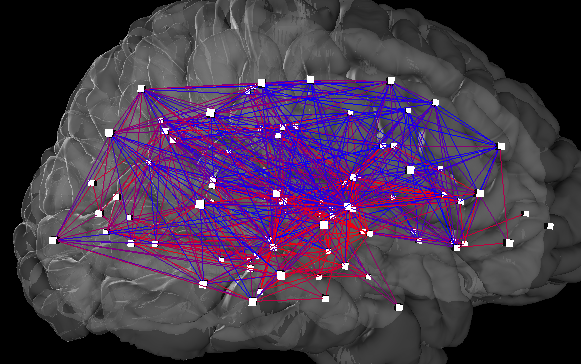

The answers to all these questions relate to the brain. Experience, awareness, and the feeling of self, and in fact all of our thoughts, perceptions, movements, and emotions, emerge from the patterns of electrochemical signals zipping along the 86 billion neurons in your brain. The human brain is the most complex object that we know of in the universe; each neuron is as complex as a major city and connects with thousands of other neurons, resulting in 300 million neuronal connections in a single cubic millimeter of brain (that’s the size of the tip of a ballpoint pen!) (Eagleman & Downar, 2016; Lichtman, n.d.). Scaling that up, the entire brain–about 1200 cubic centimeters and weighing around 3 pounds–contains about 60 trillion synaptic connections and essentially infinite possible patterns of activation. These patterns of brain activation make you, you.[1]

We are still learning about the brain and many big mysteries remain, but scientists do know an astounding amount about how the brain works. In the past decades, researchers have made tremendous progress in understanding the molecular and chemical processes in the brain, how neurons communicate with each other, the function of different brain areas and networks, how drugs and hormones affect brain function, how genes and environment shape brain and behavior, how the brain develops and changes over time, and ways things can go wrong in the brain due to damage, disease, or psychological disorders. We’ll explore these topics and more in this book on Biological Psychology.

- The nature of the self and what makes you "you" is a deep and nuanced scientific, philosophical, and even spiritual question. Understanding the nature of the "true self" is a primary goal of many spiritual traditions (Singer, 2007). For an excellent scientific resource about the nature of the self, including the brain, bodily, social, and environmental underpinnings of selfhood, see the book "Who You Are: The Science of Connectedness" by Michael Spivey (2020). ↵