Chapter 14: Biopsychology of Psychological Disorders

Mood disorders are characterized by severe disturbances in mood and emotions—most often depression, but also mania and elation (Rothschild, 1999). All of us experience fluctuations in our moods and emotional states, and often these fluctuations are caused by events in our lives. We become elated if our favorite sports team wins the big game and dejected if a romantic relationship ends or if we lose our job. At times, we feel fantastic or miserable for no clear reason. People with mood disorders also experience mood fluctuations, but their fluctuations are extreme, may last longer, distort their outlook on life, and impair their ability to function.

The DSM-5 includes two general categories of mood disorders: depressive disorders and bipolar disorders. Depressive disorders are a group of disorders in which depression is the main feature. Depression is a vague term that, in everyday language, refers to an intense and persistent sadness. Depression is a heterogeneous mood state—it consists of a broad spectrum of symptoms that range in severity. People with depressive disorders often feel sad, discouraged, and hopeless. These individuals lose interest in activities once enjoyed, often experience a decrease in drives such as hunger and sex, and frequently doubt personal worth. Depressive disorders vary by degree, but this chapter highlights the most well-known: major depressive disorder (sometimes called unipolar depression).

Bipolar disorder and related disorders are a group of disorders in which mania is the defining feature. Mania is a state of extreme elation and agitation. When people experience mania, they may become extremely talkative, behave recklessly, or attempt to take on many tasks simultaneously. The most recognized of these disorders is bipolar disorder.[1]

Neural mechanisms underlying depression

Though depression involves an overall reduction in brain activity, some parts of the brain are more affected than others. In brain-imaging studies using PET scans, people with depression display abnormally low activity in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in cognitive control, decision-making, planning, and emotion regulation.

Abnormal activity in the prefrontal cortex, especially in its lateral, orbitofrontal, and ventromedial regions, often correlates with the severity of the depression. The lateral prefrontal cortex is primarily involved in cognitive control, which refers to the intentional selection of cognitive operations, such as attention, inhibition, and working memory, in order to carry out behavior. A situation that may require cognitive control is studying for an exam while resisting the urge to check social media. The orbitofrontal cortex is mainly involved in decision-making and reward valuation. This is especially relevant for deferring immediate gratifications in order to obtain greater long-term benefits. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is implicated in a broad range of social and emotional processes such as value-based decision-making, regulation of negative emotions, and processing of self-relevant information. Indeed, disruption to these brain regions may contribute to hallmark characteristics of mood disorders, such as a bias toward negative affect and increased self-focus.

Some research indicates that the left prefrontal cortex is involved in establishing positive feelings and the right prefrontal cortex is involved in negative feelings. Typically, the left prefrontal cortex is thought to help to inhibit the negative emotions generated by limbic structures such as the amygdala, which show abnormally high activity in patients with depression. In patients who respond positively to antidepressants, this amygdala overactivity is reduced. But when the amygdala remains hyperactive despite antidepressant treatment, that patient is likely to relapse into depression. Similarly, individuals with reduced hippocampal volume seem to be more prone to relapse (Young, 2021).

Emerging work has also begun to characterize the genetic contributions to depressive disorders. Studies have shown that heritability for depressive disorders is about 40% and the risk of developing depression when a family member has had depression is 1.5-3 times higher than the general population (Fan et al., 2020; Kendler et al., 2009). Nevertheless, depressive disorders are still thought to arise from complex gene-environment interactions.[2]

Neural mechanisms underlying bipolar disorders

Research on the etiology (i.e., cause), course, and treatment of bipolar disorders (BD) have made major advances, but the mechanisms underlying episode onset and relapse remain poorly understood. BD has biological causes and is highly heritable (McGuffin et al., 2003). One may argue that high heritability demonstrates that BD is fundamentally a biological phenomenon. However, the course of BD varies greatly both within a person across time and across people (Johnson, 2005). The triggers that determine how and when this genetic vulnerability is expressed are not yet understood; however, evidence suggests that psychosocial triggers may play an important role in BD risk (Johnson et al., 2008; Malkoff-Schwartz et al., 1998). Additionally, growing research shows that bipolar disorders and schizophrenia share similar brain abnormalities and genetic substrates, which has prompted some researchers to suggest that bipolar disorders may be closer to psychotic disorders than to depression (Birur et al., 2017; Lichtenstein et al., 2009).

Biological explanations of BD have also focused on brain function. Many of the studies using fMRI to characterize BD have focused on processing emotional stimuli based on the idea that BD is fundamentally a disorder of emotion (APA, 2000). Findings show that regions of the brain involved in emotional processing and regulation are activated differently in people with BD relative to healthy controls (Altshuler et al., 2008; Hassel et al., 2008; Lennox et al., 2004). However, in individuals with BD, studies examining how different brain regions respond to emotional stimuli show mixed results. These mixed findings are partly due to samples consisting of participants who are at various phases of illness at the time of testing (manic, depressed, inter-episode) and small sample sizes make comparisons between subgroups difficult. Additionally, the use of typical lab-based stimuli, such as facial expressions of anger, may not elicit a sufficiently strong brain response.

Within the psychosocial level, research has focused on the environmental contributors to BD. A series of studies shows that environmental stressors, particularly severe stressors (e.g., loss of a significant relationship), can adversely impact the course of BD. Following a severe life stressor, people with BD have substantially increased risk of relapse (Ellicott et al., 1990) and suffer more depressive symptoms (Johnson et al., 1999). Interestingly, positive life events can also adversely impact the course of BD. People with BD suffer more manic symptoms after life events involving attainment of a desired goal (Johnson et al., 2008). Such findings suggest that people with BD may have a hypersensitivity to rewards.

Treatment

Mood disorders are also thought to be associated with abnormal levels of certain neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin and norepinephrine (Thase, 2009). These neurotransmitters are important regulators of the bodily functions that are disrupted in mood disorders, including appetite, sex drive, sleep, arousal, and mood.

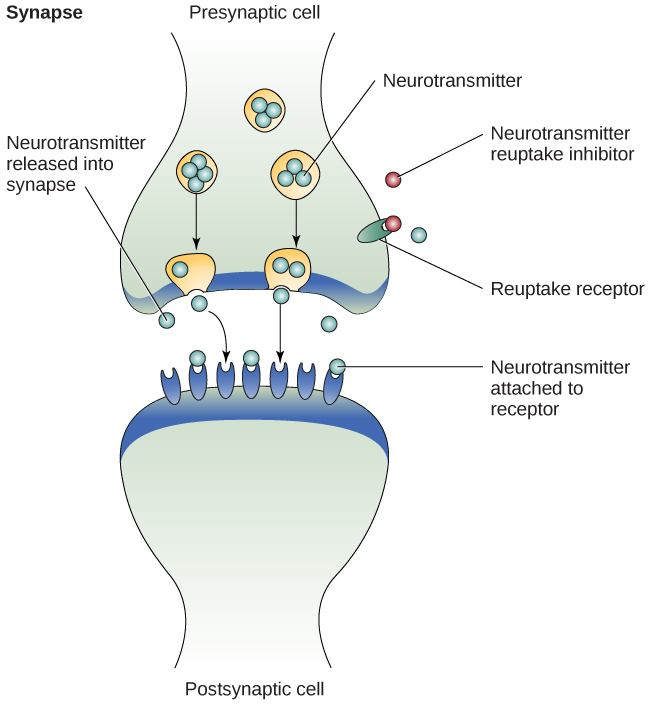

A wide variety of drugs are used for the treatment of depression. The first-generation antidepressants were developed in the 1950s and 1960s. These drugs acted to increase the action of the monoamine neurotransmitters: primarily dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. Our body uses an enzyme called monoamine oxidase (MAO) which degrades these chemicals into inactive components that do not signal at receptors. These first generation antidepressants block the action of MAO; biochemically, we call them monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). In the presence of an MAOI, the neurotransmitter signal remains in the synapse longer, similar to how an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor increases ACh signalin (Lim, 2021).

Most of the MAOIs, while sometimes effective, have fallen out of fashion clinically because of the adverse side effects associated with their biochemical activity (however, they are still commonly used in treatment of Parkinson’s disease). Some of them interact dangerously with foods rich in tyramine (particularly fermented foods, such as aged cheeses or beer, as well as beans and processed meats), an amino acid that is degraded by MAO. Excess tyramine can activate the sympathetic nervous system, and body levels of tyramine can rise to dangerous levels in the presence of an MAOI, leading to adverse cardiovascular events like stroke. Many of the common MAOIs, like phenelzine and isocarboxazid, can be damaging to the liver. Some MAOIs also produce unwanted side effects, such as psychosis or nausea (Lim, 2021).

A second-generation class of antidepressant drugs called the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), named for the shape of their chemical structure, was also developed around this time. They generally act as monoamine reuptake inhibitors, resulting in elevated neurotransmitter signaling. Unfortunately, these tricyclics may produce many severe side effects, such as seizures, tachycardia, and heart attacks, so prescriptions must be monitored closely. The tricyclics are still prescribed today for several other nervous system disorders, ranging from insomnia to neuropathic pain, but due to their potential cardiotoxicity, they are not often the first line of treatment in depression (Lim, 2021).

One of the most common classes of medications that are currently prescribed for MDD are called are third-generation antidepressants, and are focused on boosting the signaling activity of serotonin (Lim, 2021). These selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inhibit or block the reuptake of serotonin back into the presynaptic cell, which in turn preserves high levels of serotonin in the synapse that may ultimately reduce depressive symptoms (Figure 14.5). However, recent findings show that while serotonin levels rise as quickly as an hour after taking an SSRI, it typically takes several weeks for SSRIs to actually improve symptoms.[3]

For severe or treatment-resistant depression, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a treatment option. Introduced in 1938, the procedure has since been refined over the years (it is currently performed under anesthesia) and is considered to be well-tolerated and highly effective. However, side effects include aches, nausea, and memory loss (Lim, 2021).

- This section contains material adapted from: Spielman, R. M., Jenkins, W. J., & Lovett, M. D. (2020). 15.7 Mood and Related Disorders. In Psychology 2e. OpenStax. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/15-7-mood-and-related-disorders License: CC BY 4.0 DEED. ↵

- This section contains material adapted from: Duboc, B. (2002). The Brain from Top to Bottom. Mental Disorders: Depression and Manic Depression: Parts of the Brain That Slow Down or Speed Up in Depression. Access for free at https://thebrain.mcgill.ca/ License: CC (Copyleft). ↵

- This section contains material adapted from: Gershon, A. & Thompson, R. (2024). Mood disorders. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/aqy9rsxe License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 DEED ↵

A class of psychological disorders marked by severe disturbances to emotions and mood

A class of mood disorders; marked by a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest that causes significant impairments in daily life

A type of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Characterized by persistent, intense focus and anxiety over perceived body defects and flaws in appearance

Prominent feature of bipolar disorder and related disorders; a state of abnormally and persistently excessive enthusiasm and irritable mood

Covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. Supports executive functions such as goal-directed behavior, cognitive flexibility, habit formation. Implicated in many psychological disorders

Part of the prefrontal cortex that supports higher-order functions such as working memory, selective attention, and planning. It is implicated in mood disorders.

A region of the frontal lobes of the brain above the eye sockets.

Part of the prefrontal cortex that is involved in value computation, decision-making, and emotion regulation. Implicated in mood disorders

Almond-shaped neural structure that is primarily responsible for regulating emotional responses, especially fear.

Characterized by extreme mood swings from depressive lows to manic highs